Long before the Independent Media Center (Indy Media) and the “Become the Media” movement that arose out of the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle there was the Worker’s Film and Photo League. Here is a short excerpt from my book A People’s Art History of the United States that examines their legacy:

Black and Blue Filmmaking

“For me, the Film and Photo League activity was a way of life, often working all day and most of the night, sleeping on a desk or editing table, wrapped in the projection screen, eating food that might have been contributed for relief purposes and wearing clothes that were donated.” —Leo Seltzer

Mass unemployment and labor unrest was the backdrop of the 1930s and the Great Depression. Between May 1933 and July 1937 more than 10,000 labor strikes occurred. Demonstrations and marches were ever-present, as were activist-artists to cover these events. In 1930, the F&PL reported on the March 6 International Unemployment Day that took place in cities around the world, including thirty U.S. cities. The New York City demonstration at Union Square drew tens of thousands of people and descended into a full-scale riot when 1,000 police officers attempted to prevent demonstrators from marching down Broadway to City Hall. Police clubs and fire hoses battered the crowd, but no one outside the marchers and bystanders would know this from the mainstream media coverage: New York City police commissioner Grover Whalen had urged the media to minimize coverage of the demonstration and subsequent riot. Brody wrote in the Daily Worker on May 20, 1930:

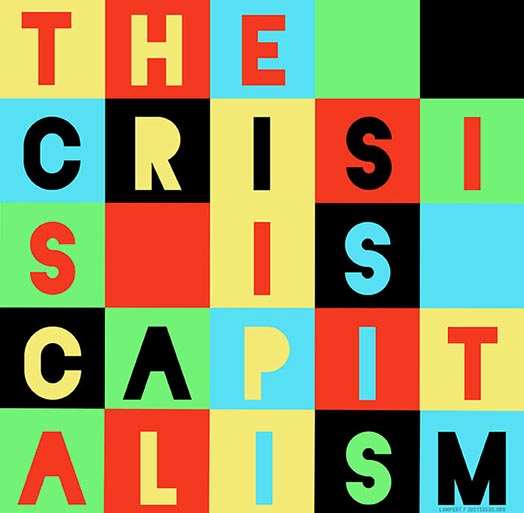

The capitalist class knows that there are certain things that it cannot afford to have shown. It is afraid of some pictures. . . . Films are being used against the workers like police clubs, only more subtly—like the reactionary press. If the capitalist class fears pictures and prevents us from seeing records of events like the March 6 unemployment demonstration and the Sacco- Vanzetti trial we will equip our own cameramen and make our own films.

This is exactly what the F&PL did, against considerable odds, given that the police targeted the F&PL as members of the demonstration, not journalists. Leo Seltzer, one of the more daring cameramen of the group, later reflected, “People would look at my stuff and they’d say, how’d you get it? Did you have a zoom lens? No! and I have black and blue marks on my hands from being beaten.” This degree of engagement produced striking film footage and still images. Seltzer adds:

The commercial newsreels had those big vans for their equipment, and they set the camera up on top. They’d park about a block away with a tele- photo lens, and their films never really gave you a sense of being involved. My film had that quality because I was physically involved in what I was filming, and that’s what I think gave it a unique and exciting point of view.

Other F&PL members echoed this sentiment. Leo Hurwitz stated that F&PL work had energy derived from a real sense of purpose, from doing something needed and new, from a personal identification with subject matter. When homeless men were photographed in doorways or on park benches, feeling guided the viewfinder. The world had to be shown what its eyes were turned away from. He added, “When you put your hand in your pocket and you can touch your total savings, your life is revealed as not the private thing it seemed before. It becomes connected with others who share your problem.”

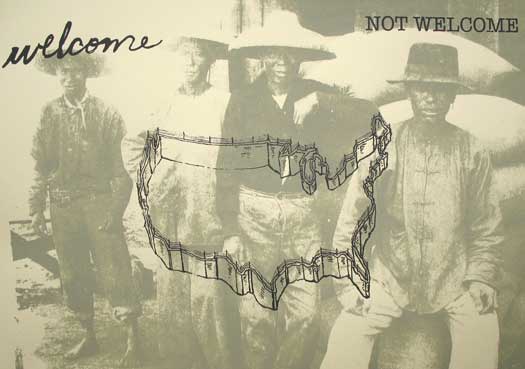

This cultural work was part and parcel with the aims of the larger Communist Party USA movement and was aimed at two intended audiences: those who partook in the same actions that the F&PL had filmed, and other workers who might be inspired by them. Seltzer recalls footage he took of a demonstration in support of the Scottsboro boys—eight of whom faced the death penalty on trumped-up rape charges:

After we marched into the area in front of the Capitol Building, I got out of the line and started shooting film. Then things started to happen. There were a lot of plainclothes men and police around. The cops jumped at this group and started ripping placards off, and beating people up.

He continues:

I was filming this one policeman. It was a rainy day, and he had on a heavy, rubberized raincoat. I was about ten or fifteen feet behind him and two or three feet beyond him was the line of pickets, with the Capitol Dome beyond that. That was the shot. And as I was shooting, the cop ran in and grabbed the placard from a black marcher and ripped the cardboard. And there was this marcher with the stick still in his hand. The marcher looked at the bare stick, and the cop was tearing up the placard which said, “Free the Scottsboro Boys,” and suddenly the marcher turned and whacked the cop left and right with his stick. And the cop was so stunned, he just stood there.

Seltzer was thrown in jail for two days, but his footage was well received by audiences when it was compiled into the film America Today and screened at theaters sympathetic to Communist campaigns. At the Acme Theatre on Fourteenth Street, Seltzer noted, “When that sequence was shown the audience jumped up and said, “Give it to him! Give it to him!” Other venues for F&PL and Soviet films were not as friendly. Seltzer recalls an event outside Pittsburgh:

I don’t know who shot the Pittsburgh film, but I went back with a projector to show it to the miners who were still blacklisted. They were still living in tents for the second winter. And I remember I went into the town and stretched this sheet between two houses—the sheriff’s and the deputy’s house on either side—and we expected to be shot at any minute while projecting the film.

Other cities were determined to stop the screenings. In New York, F&PL members were hauled into court in January 1935 for showing films in their own headquarters.In Chicago, Mayor Edward Kelly enforced a ban on all newsreel films that featured rioting or large gatherings, making it impossible to project images of strikes and pickets within the city. The situation was more volatile in the South: F&PL members were at times driven out of a town by a mob. To keep safe, Sam Brody would sleep with guns by his bed when he covered the textile strike in Gastonia, North Carolina.

http://peoplesarthistoryus.org/

http://justseeds.org/nicolas_lampert/03pahbook.html