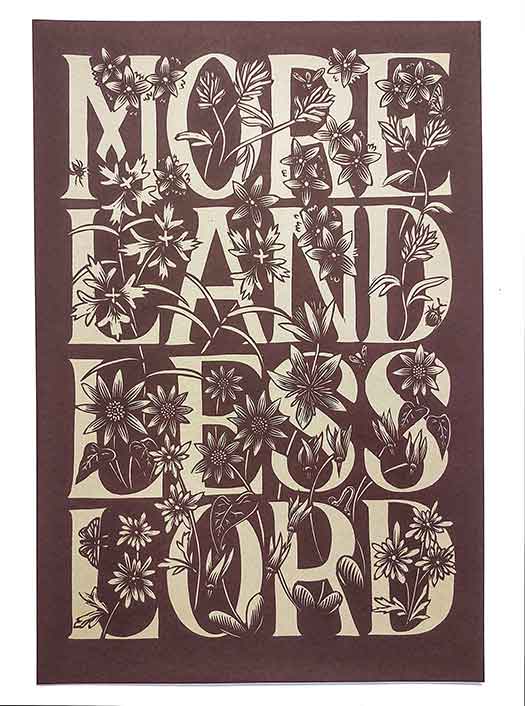

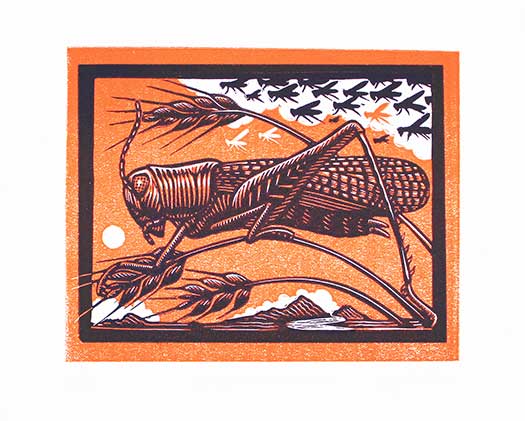

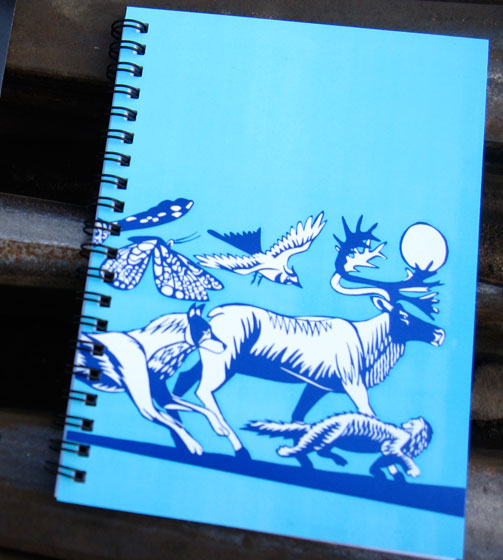

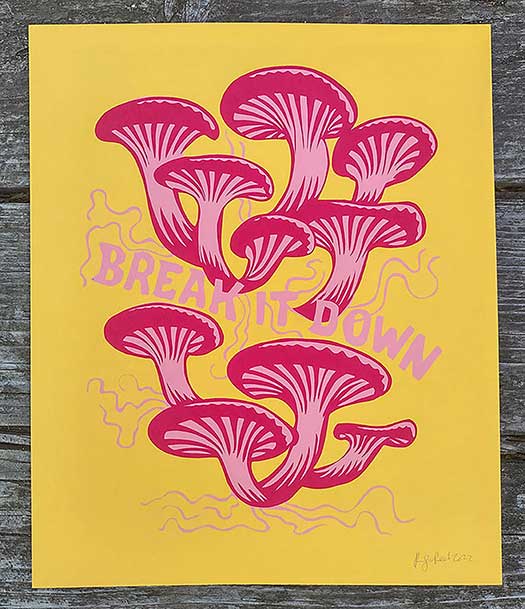

I recently had an article published in the Portland-based environmental journal Bear Deluxe about the international bushmeat trade and the effects that it’s having on the populations of our closest primate relatives; namely Chimpanzees and Gorillas. I thought I’d repost it here on the Justseeds blog so that everyone can enjoy some good, old-fashioned eco-doom hyperbole this holiday season. Included are some illustrations I did for the article. Enjoy!

At six hundred pounds, the adult male Mountain Gorilla of the Virunga Volcanoes region (comprising portions of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda) has few predators. His size brings him assurances: while almost every other primate on earth, including most of his intimate relatives, builds a nest in lofty branches or in the rotten hollows of giant trunks, the Silverback sleeps comfortably on the ground.

When he wakes, he trumpets into the dawn. He turns his face from the split roof of the forest and knuckles his way towards a clump of bamboo. He crushes the stems and scrapes out the pith with his broad teeth, lingering over some tender new growth. It’s a season of drought, and the forest is out of fruit, so he must rely on massive amounts of rough forage for his daily meal. The enormous guts that fill his cavernous chest throng with fermenting bacteria that strip out nutrients from otherwise impoverished plant material.

The lack of fruit has driven away other primates; notably absent are the Chimpanzees, for whom a diet of fronds, leaves, shoots and pith would be a death sentence. The Chimpanzees need fruit, and will take meat where they can. In this lean season they’ll be travelling alone or in small groups, opportunistic in pursuit of Colobus monkeys, into whom they will rip with the relish of an obligate carnivore. Their diet is richer, and thus their guts can be smaller, their internal microbial colonies less populous.

There is one more primate to contend with.

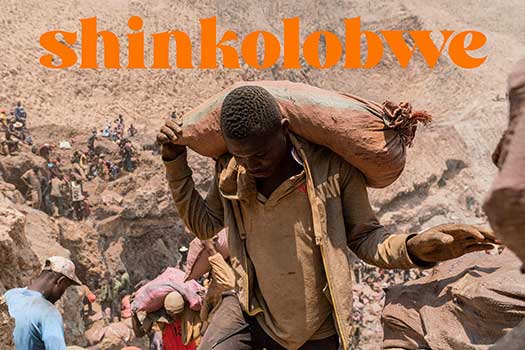

A mile away, cartridges are littered, spent, smoke curling from the freshest through the thick duff. Flies are buzzing. A man stands over an enormous pile of black fur. Sunlight shafts inward from the left, there’s an opening there: a clearcut roasting in raw sunlight. A trail of cleared vines leads from it towards the man, who has rolled the enormous corpse onto its side to facilitate its disarticulation. He’ll build a camp just inside the forest there, at the edge of the logging concession. There’ll be a pit with ashes smoldering, and racks of green twigs lashed together above it. Dried limbs and torsoes will lie shriveled and brittle in the smoke, along with the split carcasses of whatever else he manages to shoot. It’ll be a good haul, and he and his young assistant will pack it out tomorrow, hiking down the logging road towards the migrant labor camps. He’ll reserve some choice morsels for the inevitable encounter with Mai-Mai militiamen, who tax all traffic and will appreciate the offer of meat.

Several thousand miles further north, the twin steel doors of a shipping container swing open in grey London docklands, releasing a blast of flies and a sweet smoky odor. Voices rise in bargain. Someone in a uniform pockets a sheaf of banknotes and walks away. Someone else swings a pallet jack into place and shifts the blackened load out into the sunlight. More flies tornado up into the light, and the cargo vanishes into a warehouse.

This is the intersection between the world of humans and that of their close relatives, the other Great Apes: the Chimpanzees, Bonobos and Gorillas. It is the smoking heart of the bushmeat trade.

It is a great irony of this era that the greatest predator and competitor that the apes of Central Africa have ever faced is one of their closest evolutionary relatives. A smaller, balder primate, intimately related to Chimpanzees and sharing their great relish of meat. Perhaps the richest irony of all is that, of all the commonalities that bind primates together as an evolutionary clade, the clearest distinguishing characteristic of the human is that we are the only primates that cook our food. The primatologist Richard Wrangham, of Harvard, states that it is precisely that fact that has made us the creatures that we are today: small guts, big brains, small weak teeth, cooperative hunting mechanisms. These, Wrangham argues, are adaptations to the increased nutrition that cooked food makes available.

Cooking made us what we are, the world conquerors. We’ve subdued the globe, bent pretty much all of life to our collective will. Now, in the autumn of our undisputed empire, we are cooking and eating our closest relatives to extinction.

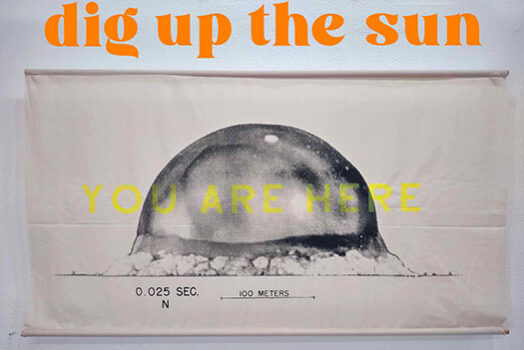

In early 2010, the United Nations Environment Programme published what they call a Rapid Response Assessment entitled “The Last Stand of the Gorilla”. The document strives to be a comprehensive analysis of the status of Gorilla conservation within the Congo River Basin- the region in which all four Gorilla species are found, which stretches from Nigeria’s eastern border to the Rift Valley. It’s a grim package of dark facts, displaying the complex synergy of human activities that conspires to extirpate animal populations in the region. The decade of ruthless warfare that so recently ravaged the Congo Basin put enormous pressure on animal populations, but in some circumstances the peace has brought greater risks: peacetime permits the development of stable markets, systems of production and export, and international networks of distribution for raw materials. Estimates of the number of Gorillas now being taken for their meat vary regionally, from 600 annually in Northern Congo to 800 in Cameroon. One study puts the take for the entire Basin at an annual total of 4,500. An unsustainable number, to put it mildly.

In Eastern DR Congo, militias have established zones of local and regional control in the aftermath of the war, often in or near national parks and preserves. They supervise and coordinate illegal mining operations that ship out rare and precious minerals to the high-tech industries of the industrialized world, and operate the enormously lucrative and destructive charcoal trade. They levy their own road taxes on all traffic within their zones of influence. The UNEP report states, with galling irony, that the peace agreements signed to end a decade of war provided allowances for the removal of army checkpoints on regional roads, with a predictable increase in smuggling and illicit taxing. The militias make staggering sums of cash from these exploits; for instance, the charcoal trade brings in upwards of $30m per year. Much of the dirty work is done at gunpoint by desperate landless people who are essentially slaves. Such a conglomeration of human hunger is purely magnetic to any entrepreneurial hunter and trapper and the meat traders with whom he collaborates, with the result that some parks and protected areas in the region have lost up to 80% of their large mammals; Hippos, Gorillas, Elephants, Chimps and other endangered species fuelling the flames of exploitation.

The peoples of Central Africa have always eaten bushmeat. Traders in regional markets display their wares without great concern for their documentation. Fruit Pigeons are stacked, smoked, on skewers, like kebabs. Duikers, Antelope, Monkeys, Agouti, it’s nothing new or shocking: people are poor in Central Africa, and bushmeat can be cheap. People need to feed their children, and everywhere people crave meat. The meat of apes, however, often has a cultural place beyond being simply protein: it is a prized treat, a delicacy, a meat imbued not just with rich, select flavor but power as well. The meat of apes makes one strong, heals illnesses, cures enfeeblement. The meat of apes is meat fit for royalty. Powerful, successful people prefer to eat foods that complement their status, and are willing to pay handsomely for the privilege. In such a situation there is plenty of money to be made.

As the cities of central Africa have boomed, a pipeline full of meat has appeared to supply them. Traditional subsistence hunting for bushmeat has largely vanished, and in its place is what resembles an industrial mechanism for the exploitation of forest products. The disassociation of urban populations from the land is much the same all over the world, but in Sub-Saharan Africa those exploding populations have kept their taste for wild meat. There’s a general lack of domestic livestock production in the forested regions of Central Africa, because the presence of Tsetse flies renders large-scale cattle production impossible. This means that almost all meat comes from the forests, forests that now lie silent and largely bereft.

As markets extend their reach, bushmeat products flow out of the Congo Basin along the same roads as the timber and the minerals. There are new roads now as well: China and the World Bank have financed a superhighway connecting the East with the capital, Kinshasa. Commerce both licit and illicit is surging as the forests and their residents are consumed. The hot, wet air is full of the crash of felled trees and the roar of yellow machinery, and below that the sound of rough picks on red earth, the growling of stomachs, the crackle of fires and small arms. Columns of smoke. Columns of flies.

The meat of Gorillas and other forest animals passes out of the realm of the parks and the militias and enters what has become a burgeoning economy in its own right, vacuuming up animals of all shapes and sizes throughout the Congo basin and beyond. Ill-lit networks of smugglers have built the trade into an economic powerhouse, joining the demands of the pet trade and the market for skins, hide and horn with the bottomless human appetite for meat.

The best prices for luxury goods are, of course, found overseas. The vastly larger incomes of expatriate African communities in Europe and the US permit greater consumption of the choicest forest meats, and as ever, entrepreneurs are swarming in to fill the gap between supply and demand. A study published in June 2010 in the journal Conservation Letters estimates an annual influx of over 270 tons of bushmeat into Paris airports. The luxury aspect of these imports is illustrated by the disparity in prices: a monkey that costs 5 Euro in Cameroon will fetch up to 100 Euro in Europe. This was the first study of its kind ever to be carried out, so unfortunately it’s not possible yet to get a handle on the degree to which the import is increasing.

Markets for bushmeat are expanding in the US as well, wherever there are sizable immigrant populations. Chicago in particular has seen several bushmeat interceptions this year, both at O’Hare airport and at African specialty stores around the city. One series of raids by US Fish and Wildlife agents netted six monkey heads, one chimpanzee head, and a variety of impaled rodents and ivory products from a dealer who has previously faced prosecution over illegal ivory imports.

The link between bushmeat and ivory illustrates the fact that the trade is being carried out by explicitly criminal organizations: all trade in ivory has been banned internationally for several decades. Many of the countries in the region also have bans on the trade in apes for pets or meat. International treaties like CITES, that aim to regulate international traffic in endangered species, focus clearly on large, rare animals like Gorillas and Chimps, but are largely ineffectual: CITES has only one enforcement agent for the entire Congo Basin. Bushmeat is now a shadow commodity, and that means money, large money.

Ofir Drori, who runs a wildlife law-enforcement NGO in Cameroon called the Last Great Ape Organization (LAGA) states that the trade in bushmeat has surpassed the smuggling of drugs in rate of return. Recent busts by LAGA include a Nigerian drug trafficker intercepted with 50 kilograms of cocaine and marijuana and the corpse of a chimpanzee, an Egyptian woman caught with several crates of chimps, and a bonobo found aboard an Air France flight. The bonobo was traced to a Ukrainian woman and a Congolese with a Russian passport, both of whom had evidence of numerous quick-turnaround return trips in their passports. Officials high up in the Cameroonian government were found to have been authorizing the shipments.

LAGA also recently intercepted several gorillas en route to a Malaysian zoo. The ominous consequences of this connection between zoos and the bush meat trade are covered in a short film called “The Kinshasa Connection”. The film (available as a podcast on Itunes) was made by Karl Ammann, a Swiss wildlife photographer and filmmaker who has spent twenty years documenting the maelstrom into which African wildlife is disappearing.

In 2006, the Los Angeles Times published an article about the purchase and sharing out of a shipment of 33 monkeys by 6 US Zoos. The monkeys were purchased from a wildlife dealer in South Africa who had in turn acquired them from dealers in Kinshasa, DRC. Officials from the San Diego Zoo claimed in the Times article that the animals were orphans rescued from bushmeat markets and that their presence at the zoo would be used to highlight the consequences of the trade. It was also revealed that upwards of $400,000 dollars had been paid to acquire them, with the aim of bolstering the gene stock of their captive breeding programs for endangered species. Karl’s investigation into the deal brought to light a quite different set of facts.

Using hidden cameras, he and his team interviewed the wildlife dealers in Kinshasa who had arranged for the transfer of the monkeys to South Africa. It became glaringly obvious that the monkeys had not been rescued from the bushmeat trade: they were in fact byproducts. All of the monkeys involved were juveniles, scooped up from beside the corpses of their mothers, who had been shot by hunters supplying meat to Kinshasa markets. The Kinshasa dealer makes it clear that many more monkeys can be acquired, but that since the last shipment raised such an enormous amount of money, his prices will understandably be going up. This is how Karl puts it, in a press release from the International Primate Protection League:

“The moment you buy primates—and they clearly were bought rather than confiscated—you create a market and a new dimension to the bushmeat trade. So rather then saving any primates from the bushmeat trade there is a high chance that you will condemn a wide range of additional primates to become victims of it. If you then combine this with press statements whereby a half a million dollars has changed hands to get these monkeys to U.S. zoos, you have every crook in Kinshasa (and there are tons of them) deciding that this is a trade where they can easily make big bucks.”

Thus, in quest of fresh genetic material to maintain captive populations of endangered monkeys, these American zoos have created a new and enthusiastic source of hunting pressure on precisely those same monkeys in their native forests. They have ensured a continuing supply of orphans, tied with string to the tables where their mothers lie cut down to weight, smoked, buzzing thickly with flies.

The orphans are everywhere. Every year, more and more and more. The pressures on populations of wild Chimps, Gorillas and other rare species have become arcane, pervasive, almost mystical. In a study published this year in the Journal African Primates, researcher Thurston Hicks describes a “wave of killing” in northern DRC forests. Orphans pile up in the markets, their incisors knocked out or burned down with hot knives. They die of malnutrition, of ill-treatment, of grief. Hicks documents the diminishment of taboos against eating certain large primates after the arrival of proselytizing Protestant missionaries. Changing beliefs unleash new waves of human predation. Hunters follow a gold rush into unopened forests, nocking poisoned arrows to their bows, and the chimps they find there are unshy of humans, unhabituated. They are easily killed. Whole troops lie in piles, swarming with flies, their eyes bulging from their heads from the effects of the poison.

The best way to rid the flesh of the taint of poison?

Cook it.

Help stop the bush meat trade!

VOTE TODAY! you’re vote counts.

Ecolife foundation is entered in a grant competition. If we win it means $100,000 to help give hunters other means of protein and income. Less orphans and less victims.

to vote:

http://disney.go.com/projectgreen/explorevote.html

for more info: http://www.facebook.com/event.php?eid=184472448231652&ref=ts

to vote:

http://disney.go.com/projectgreen/explorevote.html

shouldn’t it be “your vote counts??”