Political art is a powerful tool, but not every work penetrates the public imagination, and most fall far short. Sometimes, however, a single timely image captures precisely the attention of the audience it’s intended for and explodes across the landscape of media and politics, metastasizing into the symbol of a movement.

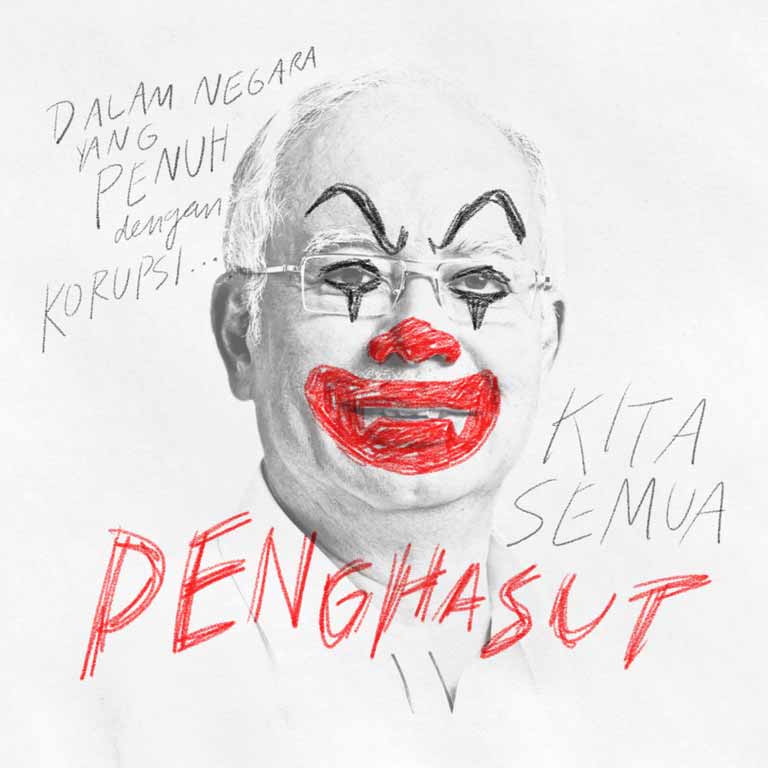

Malaysian graphic designer Fahmi Reza saw this happen to one of his images last year, when a graphic he created of the Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak in clown makeup infected the internet, spreading in real-world and digital form across the country and drawing the eye of the intolerant and brutal Malaysian state to Fahmi.

This interview was conducted by me via email, with help on questions from Josh MacPhee.

1. What’s the background of the Clown graphic, and can you give a short summary of the story so far?

In late 2015, the Malaysian Prime Minister, Najib Razak was facing widespread accusations of corruption involving a state-owned investment fund known as 1MDB. Billions of dollars were siphoned from this fund which Najib oversees, with US$681 million allegedly transferred into Najib’s personal bank accounts.

But a few months later, in January 2016, the Malaysian Attorney General closed the corruption investigation against Najib, exonerated him of corruption allegations, cleared him of political wrongdoing, and accepted Najib’s claim that the US$681 million was a donation from a Saudi royal family.

A lot of people here were outraged by this announcement. I immediately came up with the first graphic of Najib with an evil clown make-up and posted the image on my social media accounts on 30th January 2016 as an act of protest against all the bullshit and lies that he used to cover-up his corruption that had turned the whole thing into a circus and a joke.

The first poster of the clown came with a scribbled slogan that reads, “Dalam negara yang penuh dengan korupsi, kita semua penghasut” (In a country full of corruption, we are all seditious) which was my response to an Amnesty International report that states that in 2015 alone, the Sedition Act, which is a law that is frequently used by the government to restrict freedom of expression, was used 91 times to arrest, investigate and charge individuals for making comments or actions deemed critical of the government.

Within 3 hours after I posted the clown poster on social media, I received a warning from the police on Twitter, telling me that they’ve placed my Twitter account under police surveillance and warning me to use it “prudently & according to the law”. In defiance, I reposted the same clown poster on Twitter along with the hashtag #KitaSemuaPenghasut (#WeAreAllSeditious).

This small act of defiance had sparked a nation-wide grassroots protest movement centred around clown image of the Prime Minister, transforming it into a Malaysian symbol of protest against government’s corruption, in defense of freedom of expression and our right to dissent. I think as a visual protest symbol, the clown image of the Prime Minister came out at the right time. The timing was perfect.

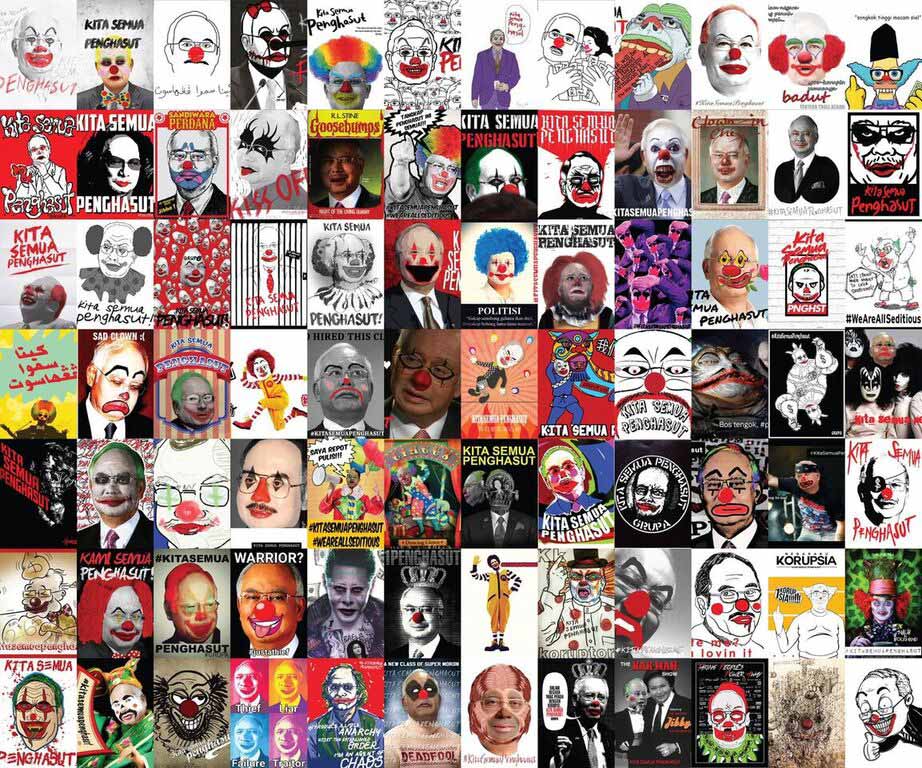

Other local graphic designers started producing their own protest posters featuring the slogan “Kita Semua Penghasut” (We are all seditious) with their own version of Najib with clown make-up, and flooded the posters on social media. In total around 100 posters were produced.

Around 40 DIY t-shirt printers all over the country started printing and selling protest t-shirts of the clown graphic along with the slogan “Kita Semua Penghasut”. Within a month they’ve sold a combined total of around 3,000 t-shirts. Kids who bought the t-shirts were enthusiastically sharing selfies of themselves wearing the t-shirt on social media using the hashtag #KitaSemuaPenghasut as a way to express their protest and dissent.

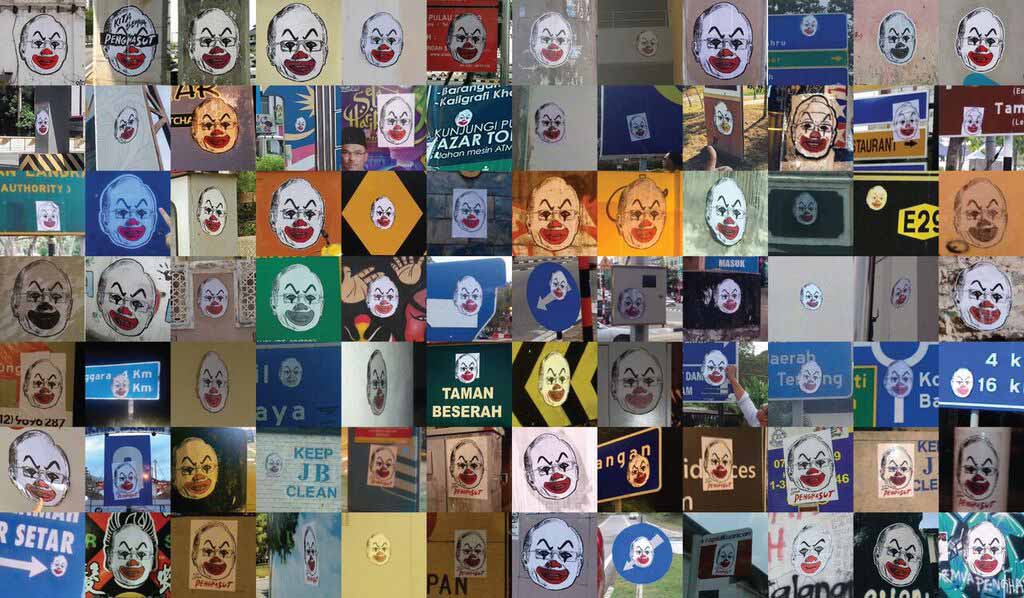

And then there was the guerrilla street art campaign. Kids started downloading the clown graphic and printed them out as stickers and posters. Within a month, 80 wheatpasted clown posters of different sizes, even as big as 8 foot tall, and hundreds of stickers started popping up on street walls in over 30 cities nationwide.

But the government was not amused. All of these led to my arrest and charges in court.

2. Most people reading this interview will likely be living in must less directly repressive contexts. How has the clown campaign affected your ability to live and survive? The repression looks really intense and severe from afar, but it has also appeared to make you into a minor celebrity. How do you pay your rent?

After I received the warning on Twitter for the first clown graphic, the police opened a criminal investigation against me. In February 2016, I was called in for questioning twice over my social media postings of two different clown graphics. In March 2016, the police and immigration placed me on a travel ban, blacklisting me from travelling overseas. In June 2016, I was arrested under the Sedition Act for selling protest t-shirts with the clown graphic on it. In that same month, I was charged in court under a section of Malaysian communications and multimedia laws that made it a crime to disseminate online content deemed to “annoy another person”. I’m currently facing 2 different criminal charges, and is still awaiting trial. If convicted for both offence, I may face prison time up to two years or a fine of RM100,000 (US$22,400) or both. All this for the crime of posting a bunch of clown graphics of the Prime Minister on social media.

In November 2016, I was arrested again for carrying the clown graphic as my protest sign during a massive protest in Kuala Lumpur that saw thousands of people marching against the government. I spent two nights inside police lock up, under suspicion of “attempting to riot” with my clown protest sign. It was clear that all these investigations, arrests and charges were meant to punish me for standing up against the government using my art as my weapon, and to deter others from doing the same.

All these repression; getting arrested, investigated and charged is making me more known to the public and giving me more exposure, but it’s not helping me get more freelance design work. I actually got less design work because of it. But I still manage to pay the rent and make ends meet by doing other types of freelance work.

This is not the first time I’m being targeted by the authorities. Being a politically conscious graphic designer, I have been openly critical of the government in my work for the past 15 years, and have been arrested, banned and prosecuted for my art and activism before this.

3. Here in the US we have a culture that on the surface is much more permissive. We are allowed to make fun of our public officials, to the point where they have learned how to thrive off the the negative attention, as witnessed by Trump’s ability to convert almost any bad press into an advertisement for his “rebelliousness” and “outsider” status. Does Malaysia have a culture of political satire?

In Malaysia most people are afraid to make fun of those in power. Political satire is a much more dangerous game over here than it is in the US. The ruling elite here don’t have a good sense of humor, and will treat any form of political satire or parody against them as an act of sedition or defamation. In the past the authorities have issued stern warnings and taken severe actions against political cartoonists, writers, musicians, theatre directors, and even bloggers and Youtubers for producing satirical work that they considered “offensive” and “disrespectful”. In Malaysia it is permissible to make fun of politicians from the opposition parties, but if you try to do the same with politicians from the ruling party, you could end up getting arrested. We had a culture of political satire for a long time in the past, but it has been replaced by a culture of censorship by this increasingly authoritarian ruling party that have been in power for the last 60 years.

4. The over-the-top reaction to the clown campaign makes Razak look defensive and ridiculous to people in the west. Is there any way he could coopt that? When we draw caricatures of politicians, we are simultaneously critiquing them and increasing their pubic representation. Are you concerned that if Razak survives the clown campaign, it could end up making him look even more powerful? What would happen if Najib Razak woke up with a sense of humor, and embraced the clown persona?

Even though he’s the most powerful man in this country, I think you are overestimating him. He’s not sophisticated enough to do anything like that. I am not at all concerned that Najib will suddenly embraced the clown persona one day. I don’t see that happening. He’s just too authoritarian. I believe he will continue to crack down on political satire or any forms of criticism that can challenge his authority.

5. Do you see the social media aspect and the guerrilla street art parts of the clown campaign as necessarily connected? Could you have one without the other? Do you see one as more important?

The social media aspect is definitely connected to the guerrilla street art component because the whole campaign wouldn’t have taken off without social media. The street art component was sparked by photos that I shared on social media of the first large wheatpaste clown poster getting torn down in less than 8 hours after I put it up in KL. In defiance, other people started downloading the clown graphic and pasting them up in their own cities and towns. They in turn started sharing photos of their clown posters and stickers on their own social media accounts, with the hashtag #KitaSemuaPenghasut. You couldn’t have one without the other.

6. Beyond sharing the images online and on social media, how active have others become in the campaign? Are people you don’t know printing stickers and posters and posting them up? You’ve been traveling to talk about the project- how have the reactions been in other places, like Taiwan?

Earlier on I’ve uploaded hi-res files of the clown graphic poster and sticker templates on Mediafire and other file sharing sites for people to download and print themselves. Looking at the download counter, the clown graphic poster have been downloaded 6,801 times, while the clown sticker template have been downloaded 7,558 times. Within one month, 80 wheatpasted clown posters started appearing on street walls in over 30 cities in Malaysia. I lost count on the number of stickers, there was too many. I don’t even know any of these people who are downloading, printing and posting these posters up. Some of them will send me photos of posters and stickers that they’ve pasted, while others have shared them directly on social media with the #KitaSemuaPenghasut hashtag.

Even though the clown graphic went viral online and offline, there was a total media blackout in the mainstream press in Malaysia about the clown graphic and the grassroots #KitaSemuaPenghasut protest movement that was sparked by it. For four months when the protest image was spreading all over the place, from selfies of people wearing the clown protest t-shirts to clown protest posters on street walls, none of the mainstream news media reported the story. Only in June last year they started publishing stories about me being charged in court with negative news headlines that reads “Pereka grafik didakwa muat naik gambar palsu PM” (Graphic designer charged for uploading a false image of PM) and “Imej Badut Aib PM, Pereka Grafik Didakwa” (Clown image humiliates PM, graphic designer charged).

Surprisingly the whole campaign received some pretty good press coverage in other places overseas. Last month I got nominated for this year’s Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards in the UK, for the whole clown campaign and my defiance in the face of adversity. Abroad I’m being celebrated for it, but at home I’m being persecuted for it.

7. It’s hard for us to tell here in the U.S., so just how popular is the project and the caricatures in Malaysia? Is there a sense of growing opposition to those in power, and if so do you feel like you are a part of it?

There is definitely a sense of growing opposition to those in power. Right now in Malaysia, the culture of protest and resistance is growing stronger, especially after the rise of larger social movements like ‘Bersih’. People are no longer afraid to express their dissatisfaction and criticism against the government, and are beginning to see the power of social movements. In December last year, thousands of people marched in the streets of KL during the ‘Bersih 5’ rally to protest against government’s corruption. The clown graphic was visible throughout the protest, emblazoned on t-shirts, placards and protest signs. I am definitely part of this growing resistance, with my design as my weapon. The fact that I was targeted by the police, immediately arrested and locked up after the rally is a testament to this.

But at this stage in time, we are not yet powerful enough to stand up against Najib and his corrupt government. We are not strong enough to pressure the existing political institutions to bring him to justice. We need to continue to mobilise the people to put a more tremendous amount of pressure on the government to act. I believe in ‘people power’ and the power of social movements to affect change through collective actions, demonstrations, marches, strikes, direct actions and civil disobedience. One day we will bring him to justice.

8. What’s next? How do you build off this platform that has been created?

Because social movements do not win overnight, we need to continue the process of raising consciousness, getting organised, mobilising citizens, taking actions, building networks, creating alternatives, and a lot more. I believe we need to nurture more activists and develop more ‘rebels’ to fight for change in this country. I hope to see more artists and designers getting involved in the struggle, with the courage to stand up against injustice, to speak out against corruption, to use their art as weapons for change.

Thanks to Fahmi for such exhaustive responses. Follow him on FB here.