So, here is the English version of the article I had published in Zapruder magazine. This is a much longer version, very much still in process. I’d love to hear what people think, so please comment if you read it!

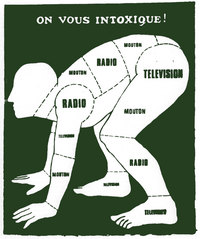

In most societies, very few people have access to the mechanisms of mainstream media creation and distribution. Most of us have little to no input into the barrage of headlines, advertisements, news briefs and billboards we consume everyday. As such, this visual landscape often feels more like a system of control than a source of useful information. When these “legitimate” systems of communication fail individuals or groups in a society, people often turn to illegal ways of communicating with both each other and the system attempting to control them. Graffiti and street art have long existed as a safety valve for individuals to vent their anger and frustration, whether in the form of scrawling angry messages on bathroom stalls or pasting posters on the windows of government buildings. But it is when the vast majority of people begin to feel that they have no other outlet to communicate, that the media channels open to them are uni-directional and they are on the receiving end of a string of lies and half truths, that street art can act as an antidote to our visual space being used as a social control mechanism. There have been many of these moments, when street art becomes truly democratic and hundreds, or thousands, of people flood the streets with their messages in the form of posters and graffiti. It is at these times that people begin to look to the streets, and to their peers, to find explanations for their condition, not corporate television, state radio, or ruling class newspapers. I’m going to discuss four historical examples here; Paris in May 1968, Nicaragua in the late 1970s, South Africa in the early 1980s, and finally Argentina from 2001-04.

Part I: France

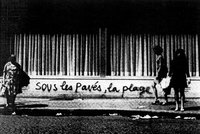

In Paris, in May and June of 1968, there was a student and worker revolt that brought France to the brink of revolution. Accompanying this revolt was a groundswell of creative street expression, especially in the form of graffiti’d poems and slogans and rapidly mass-produced silkscreened political posters. The posters often responded to the direct material reality of what was happening on the streets and in the factories, while the graffiti was largely more poetic and metaphysical, speaking to its readers on a much more emotional level. This counter-narrative written on the street not only attracted people because of it’s graphic power or sense of humor, but also because there were days at a time when the workers in French TV, radio and press were on strike. The walls were literally the only place to get the news.[1]

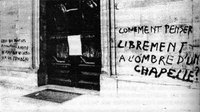

Almost 40 years on it’s nearly impossible to say who wrote which graffito, or exactly how many people were involved in covering the walls of the streets and universities. It is fair to say that this was an extremely popular action, a book published in Paris in June of 1968 collected 578 unique slogans scrawled around the city.[2] It is generally accepted that much of the graffiti was written or inspired by a radical group of students called the Enragés, who in turn were inspired by the writings of the Situationists, an international group of radical anti-capitalist theorists.[3] Angelo Quattrocchi is an Italian anarchist that was in Paris at the time and wrote about the graffiti:

The people, fresh and tired from the action of the streets and the mind. Rather uncomfortable in their own skin and bursting to speak.

They start writing furiously on neutral walls.

‘Power to the Imagination’

Imagination is taking power.

Escalating over the horizons and reporting back to mortals.

White paint, red paint, black paint. Paint.

Stones in ponds, gentle ripples.

‘I take my desires for reality, for I believe in the reality of my desires’: Anonymous. 1968…

A galaxy of poets. The vertigo distillates its words.

Arrows lost in the sky.

‘Art is dead, don’t eat its corpse.’

Revolution is the ecstasy of history.

‘Those who make revolution by halves, dig their own graves.’

The mystifications are very old:

‘How can one think freely in the shadow of a steeple.’

And very new:

‘Commodities are the opium of the people.'[4]

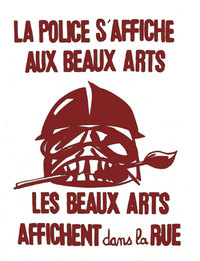

In addition to the graffiti, posters completely covered the Latin Quarter of Paris, and spread out from there. Dozens of individuals and groups produced posters during this period; the most prolific production groups were the Comite’s D’Action, the Atelier Populaire des Beaux-Arts, and the Arts-Décoratifs’ workshop (whose main members founded the political design collective Grapus one year later). The Atelier Populaire alone produced somewhere between 350-500 poster designs and hand silkscreened 120,000-150,000 total posters in May and June of 1968. The Atelier was set up when 200 revolutionary students occupied the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris’ most prestigious art school, and together with members of the Jeune Peinture (Young Painter) group, set up an ad-hoc poster factory. Their posters were collectively made, with artists meeting with students and workers in a general assembly every day, to both plan out slogans and graphics, which were chosen by committee, and discuss larger political problems. Simplicity and efficiency were the rules of the day, with a drive to making the most direct graphic interventions possible. Students and workers came in and out of the studio, reporting on all the activities going on in the street and bringing in statements made by government officials, university administrators, and union bureaucrats.[5]

This act, putting art in the service of the political struggle, should not be undervalued or underestimated. The artists at work at the Atelier believed they were on the edge of a new world, one in which their art would have meaning beyond commodification and the logic of the market. Another Atelier statement reads “Bourgeois culture separates and isolates artists from other workers by according them a privileged status. Privilege encloses the artist in an invisible prison. We have decided to transform what we are in society.”[7] A member of the Atelier, Gérard Fromanger, remembers the beginning of the occupied workshop and tells the story of their first poster. They produced 30 copies of it with the intention of selling it in a gallery down the street, but before the posters can even get there, they are grabbed out of the carrier’s arms and pasted onto the street. Art is no longer separate from everyday life, but takes on a new vibrancy and purpose.[8]

Part II: Nicaragua

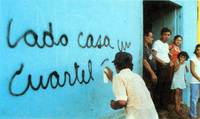

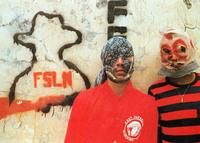

In July 1979, the people of Nicaragua carried out a successful revolution over Anastasia Somoza, a US backed dictator. The revolution, largely carried out by the FSLN (Sandinista Front for National Liberation, or Sandanistas for short) was preceded by decades of political organizing and guerilla military activity against Somoza, and over 100 years of resistance to US intervention in the country.[9] An integral part of this activity, at least since the mid 1960s was the pinta, what the Nicaraguans call a graffiti’d political slogan.

Omar Cabeza, one of the Sandanista guerilla’s and eventual FSLN politician, claims that the pintas began in 1965, and largely came out of student activism in urban areas through 1968. In 1969 the use of the pinta became more generalized, with more people writing them and the act itself being absorbed into the more serious political organizing of the FSLN. He describes writing the graffiti like this:

“…one would always go with one’s ‘compañeros,’ sometimes with a car, at night or at dawn, in darkness. One of us would stand on one corner and another on the other corner. Then one guy in the middle would paint. When the guardia came, we would hide everything in the car and drive off normally. That was the ‘nocturnal pinta.’ In the beginning, if they caught you painting ‘pintas,’ they would arrest you, convict you and give you six months. Later, when the repression was increasing, if the guards caught you painting, you were a dead man.”[10]

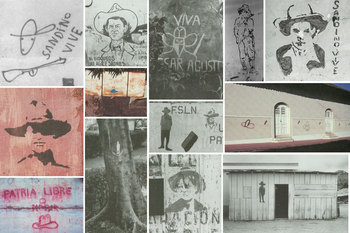

One of the most interesting and specific developments of street art in Nicaragua is the near universal use of the image of Augusto Sandino on the walls. Sandino was a Nicaraguan nationalist and revolutionary in the 1920s and 30s who fought off the US military from the mountains of the country for almost a decade. Sandino had a very specific look, like a militarized horse wrangler, always with a giant cowboy hat perched on his head. It is this cowboy hat that became a universal symbol of resistance in the country. Priest, poet and revolutionary Ernesto Cardinal states, “I believe that Augusto César Sandino is the only hero in history who is recognized by his people by his silhouette alone. The silhouette of Sandino is everywhere in Nicaragua — on walls, on ramparts, one fences, on curbs, on columns, on bridges, and even on electric and telephone polls.”[14] From the 60s on, thousands of Nicaraguans represented Sandino via graffiti on the street, sometimes in the form of intricate full body stencils, sometimes as a solid profile of a man with a hat, and more often then not simply as a stylized cowboy hat, a figure eight tipped on its side with a humped arch painted on top. There are nearly as many representations of Sandino as there are Nicaraguans who fought for a better country. Unlike ubiquitous representations of Lenin, Stalin or Mao, the grassroots and democratic claim to Sandino’s image and the continuous defining and redefining of his meaning make it extremely difficult for him to loom over the people, to be above critique, to exist outside of the rabble that creates him. Joel Sheesley has said, “Sandino’s heroism cannot be mythologized in closed quarters under bureaucratic authority. He is a folk as well as a political hero. He has become a people’s as well as a party’s symbol. The incipient anarchy of collage in the streets is inimical to bureaucratic consolidation.[15]” This democratic voice swept away the power of Somoza’s dominant narrative, and eventually Somoza himself.

Part III: South Africa

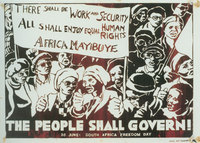

In the late 1970s, there was a huge youth uprising in South Africa against apartheid, and mass resistance to decades of the strict enforcement of laws prohibiting anti-apartheid organizing, anti-racist activism, and independent union activity. In the early 1980s the government attempted to quiet the movement with some basic reforms and, at least officially, a brief thawing of repression. The African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Communist Party (SACP) were still officially banned, and hundreds of their members were in prison, but in 1983 the United Democratic Front (UDF) was formed, bringing together more than 600 youth groups, student organizations, unions, church and civic groups and women’s organizations. This brief explosion of public and open organizing was shut down in 1985 by the first of a series of States of Emergency, which plagued the country for the rest of the decade.[16]

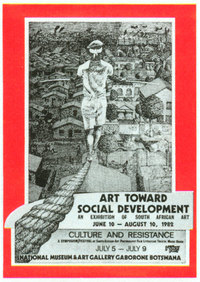

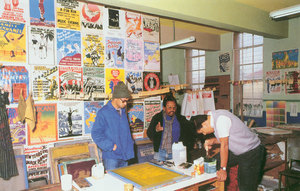

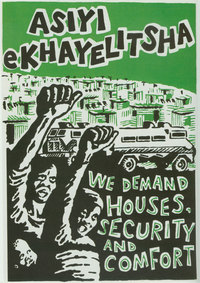

Meanwhile in 1978, just across the border in Botswana, a group of exiled South Africans formed the Medu Art Ensemble. Medu was a grouping of self-defined “cultural workers” who produced theatre, music, literature and graphic arts in support of the anti-apartheid struggle. Eventually they consolidated into an exile propaganda wing of the African National Congress. Although there was often a lead artist, Medu designed posters through collective discussion amongst many members, including those not involved in the visual arts. Medu produced over fifty posters, many with the intention of sending them into South Africa, giving voice to the struggle against apartheid. These posters would then be illegally posted in public. Medu included trained artists and designers, and their posters are accomplished political graphics. But they also wanted the South African movement to develop the silkscreening of political posters as a mass communications tool, since silkscreening takes little capital and set up, and can be easily taught to militants across age, race and gender. In July 1982, Medu organized the Culture and Resistance Festival in Botswana with the theme “political struggle is an unavoidable part of life in South Africa, and it must therefore infuse our art and culture.” 5000 cultural workers came from South Africa to participate.[17] In 1984, Medu proposed the creation of the “silkscreen workshop in a suitcase,” a all-in-one portable container which held a silkscreen, ink, squeegee and stencil making material. The goal was to distribute these to organizations so they could make posters under the most oppressive conditions.[18]

Right after the conference, the government banned Medu posters, forcing them to be smuggled into the country. In 1985 South African army units crossed the border and murdered twelve Medu members and destroyed the houses of others. The remaining members were forced underground and Medu ceased to exist. But in response to the conference, silkscreen workshops had been set up domestically which could produce and distribute posters more immediately and effectively. Two of the biggest were the Screen Training Project (STP) in Johannesburg and Community Arts Project (CAP) in Cape Town. Both projects were intended to be training programs so that militants from around the country would gain the skills and the set up their own production facilities locally. Some of this occurred, but with the forming of the UDF, their was such a huge demand for posters and propaganda that both workshops got caught up in direct production, trying desperately to produce what was immediately needed for the movement and barely having time to keep training new silkscreeners.[19] Like the Paris 1968 posters, these were being produced in the spur of the moment, responding to what was immediately going on in the struggle. But unlike the Atelier Populaire or Medu, few if any of the members of these projects had formal art training, so the designs were often extremely raw and naive, awkwardly designed and poorly printed. Interestingly, a number of them actually borrow heavily from, if not outright copy, Paris 68, and even older Russian and German, political posters. Even if untrained, South African activists seemed clearly aware of the history of Left posters and propaganda.[20]

The streets of South Africa were covered with posters and the movement was gaining visibility and momentum. Although repression had supposedly thawed, only 6 months after they started the Screen Training Project (STP) had their space broken into and equipment destroyed. A year later the police confiscated a large amount of their posters, and then in 1985 an STP worker was detained for 4 months with no explanation ever given. This same worker was detained again in 1986, and this time the police claimed he was “the co-ordinator of the so-called screen programme, and organization responsible for the printing and distribution of subversive literature…and the training of Black Youths.” This and other repression eventually forced the STP underground. The Community Arts Project also faced harassment, but never to this degree and remained active aboveground.[21]

Both CAP and STP were able to reach some of their training goals, and a number of small local workshops opened up in other parts of the country. Many were centered in communities that faced forced removal into government Bantustans. The Lesedi Silkscreen workshop was started by the Huhudi Youth Organization, who trained at STP in 1984 and started printing on their own in 1985. These smaller workshops often faced even harsher repression. A member of Lesedi remembers, “The people of Huhudi started printing posters at the Lesedi workshop in 1985. The reaction of the state was swift. The workshop was petrol-bombed, some activist detained, others fled the country. The States of Emergency imposed after 1985 eventually forced Lesedi to close.”[22]

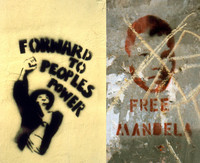

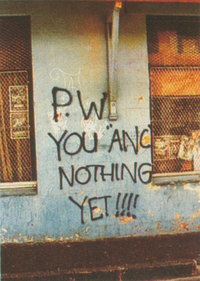

Parallel to poster production was the mass use of graffiti and t-shirts to spread anti-apartheid messages. Likely beginning much earlier, but really exploding after the first State of Emergency was imposed, graffiti in the form of scrawled political messages or much more graphic and designed stencils started covering the walls of the country. When most forms of public protest were banned, graffiti became a way for social movements to communicate to each other, the larger population, and the apartheid government. Like in Nicaragua, the intended audiences of the graffiti were both sympathetic community members and the security and police forces. This anti-racist graffiti was often responded to with right wing graffiti, converting slogans like “Free All Detainees” to “Freeze All Detainees.” Graffiti wars covered the walls, with each side crossing out or changing the other’s slogans. The right wing writers had the advantage of not being afraid of the police (or sometimes even were police), so they were able to paint in broad daylight, and as large as they wanted, but the anti-racist writers tended to be much more prolific. The slogan painted most often was “Free Mandela,” sometimes accompanied by a stencil of his face.[23] Unlike the Sandino images and their myriad meanings, the graffiti of Nelson Mandela, imprisoned leader of the ANC, expressed one clear message: You can lock us up but we will keep fighting — even imprisoned, Mandela is present and part of the struggle.

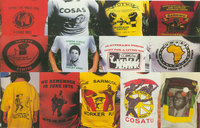

Although not exactly street art, t-shirts played an important role in the rewriting of the visual landscape in South Africa. When most other forms of protest were banned, activists started producing and wearing hundreds of different political t-shirts, spreading their messages far and wide on people’s chests, and literally embodying the politics. Funerals became an important outlet for shirts. Most political organizing was banned, but tens of thousands would come to the funeral of a fallen activist, and everyone would where special t-shirts to pay homage to the individual that died and the politics of the movement. Eventually the state began banning t-shirts, and even arresting some people for wearing them.[24]

Posters, graffiti and t-shirts changed the struggle against apartheid. They made public a fight that had been bubbling in hiding for decades. A voice was given to a mass movement that never before had seen or heard its complete collective power. The education system, propaganda, and media of the apartheid regime just couldn’t keep up with the release of this voice and South Africans began to be able to listen to and see what each other were saying in a whole new way. As South African artist Sue Williamson wrote at the time, “as press censorship increases, the writing on the wall has become required reading.”[25]

Part IV: Argentina

And finally my most contemporary example, the recent uprising and struggles in Argentina in 2001 to 2004. Rocked by IMF austerity programs, the economy of Argentina nearly collapsed at the end of 2001. Having no faith in the economy, the middle class started taking huge amounts of money out of the banks, so the government placed limits on the amount of money that could be withdrawn. In December, Argentina defaulted on its IMF loans and the bank owners began loading money out of the banks into armored trucks and driving it out of the country. On December 19th and 20th the people of Buenos Aires responded, taking to the streets in the hundreds of thousands, banging pots and pans, smashing bank windows and ATMs, and demanding “¡Ya Basta! [Enough!]” and of the politicians, “¡Que Se Vayen Todos! [They All Must Go!].”[26]

Although the insurrections were very different, it’s impossible to not compare the look of the streets of Buenos Aires to those of Paris in 1968. Almost overnight the walls were covered with political slogans and poetic stencils. Also like Paris, there was a sense of play in the graffiti not entirely present in South Africa or Nicaragua. Like very successful advertisements, with bits of poems and twists of phrase, the graffiti often spoke on both conscious and subconscious levels. Community, political, and workplace organizations did much of the graffiti. A friend who was in Buenos Aires at the time told me that rarely would a meeting go by where there wasn’t a subgroup assigned to stenciling and graffiti. This was a popular art form, taken on by kids very comfortable with vandalism, as well as adults who had never held a spray can before.[27]

There were also the stencil collectives, BSAS Stencil and Vomito Attack being two of the most prolific and effective. These artists, like those of the Atelier Populaire, at least temporarily turned their skill sets wholeheartedly over to the larger social upheaval, designing extremely powerful images and covering the streets, from direct attacks on politicians to more metaphysical statements on the nature of Argentine life during and after the crisis and revolt. Erick Lyle discusses one of BSAS Stencil’s graphics: “My favorite this night was the image of a bus, speeding down the street, with ‘inconsciente‘ (unconscious) written on the side. Busses in Buenos Aires are known as ‘colectivos.’ ‘Colectivo‘ means collective. All at once, I see the bus and think, ‘collective unconscious’. It is both fun and evocative. I think of the image speeding along the walls of Buenos Aires and think of Argentina, all aboard the bus for wherever the ride takes them for these four years, as the country’s collective unconscious, the common language, appears new and freshly painted each morning on the streets.”[28]

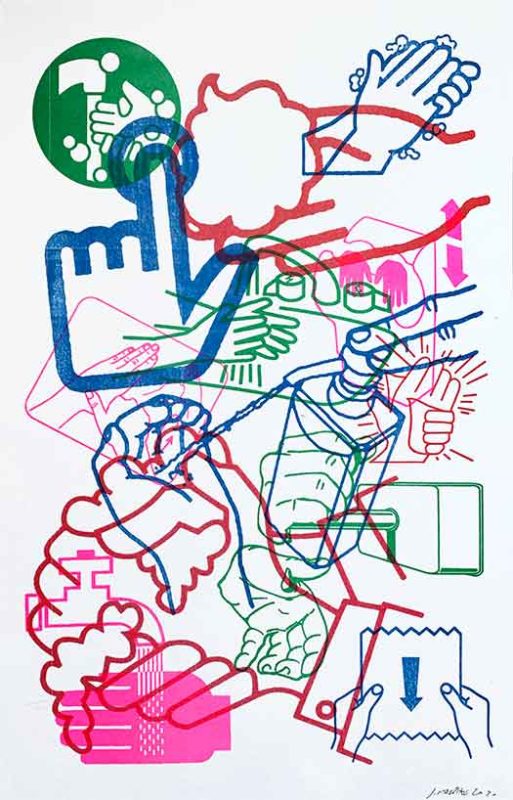

Even more styled after the Atelier Populaire was the Taller Popular de Serigrafia(TPS), which formed in 2002 out of a silkscreen class organized by the Popular Assembly of San Telmo, a directly democratic organization of the residents of the San Telmo neighborhood in Buenos Aires. TPS produced over sixty five graphics in direct service of the uprising and particularly the occupied factories movement, paralleling the Atelier‘s support of occupied factories on May 68. These images were distributed via silkscreened posters and also, echoing South Africa, T-shirts. Members of the Taller would set up a simple silkscreen apparatus at protests and screen their images onto anyone’s shirts for free, reproducing their images by the thousands at each event. They did this live printing at more than fifty protests.[29]

Although very little, if any, of the Buenos Aires street art makes reference to or critiques the mainstream media, there is no question that for at least December 19th and 20th, 2001, if not for weeks after, the streets were where people looked to for their news. Television and most radio was owned and controlled by the same ruling class which had just fled the country with everyone’s money, and most programming attempted to ignore what was going on in the country. On the screen inside were the normal soap operas, sitcoms and reruns while outside the window hundreds of thousands banged on pots and pans and were shot at by riot police. The distance between fiction and reality was just too great, the glow of a Hollywood action movie on the TV screen just couldn’t compete with the action of everyday life.[30]

Conclusion

Street art can be instrumental in the creation of democratic space. As the examples I’ve discussed above have shown, it can make transparent the systems of control in our environment, bringing courage to those being controlled, and fear to those doing the controlling. But I can’t stress enough the importance of the connection to larger social forces. Street art is a dynamic tool which can be wielded for social transformation, but it does not create revolutions alone.

Our visual space is a complex environment, and it is easy to simply create the illusion of democracy, rather than democracy itself. The reclamation of visual space has to set the stage for our interventions deeper into physical space. It is in the interest of the status quo to relegate all matters of political importance to the two-dimensional world of the advertising wall, the billboard and the television screen. As the media theorist Stuart Ewen has said, “By reducing all social issues to matters of perception, it is on the perceptual level that social issues are addressed. Instead of social change, there is image change.”[31] We need to occupy not just the exterior, but the interior of our world as well. This can only happen through organization and political struggle. Powerful propaganda and witty slogans fall on blind eyes and deaf ears if they don’t interlock with activities that can truly change how we live and experience our lives.

Notes:

1. Kristin Ross, May ’68 and its Afterlives (Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 2002), 3-4. See also: Alan Priaulx & Sanford J. Unger, The Almost Revolution, France–1968 (New York: Dell Publishing, 1969).

2. Claude Tchou, ed., Les Murs Ont la Parole Mai 68 (Paris: Tchou, 1968).

3. See: René Viénet, Enragés and Situationists in the Occupation Movement, France, May ’68 (New York: Autonomedia, 1992).

4. Angelo Quattrocchi & Tom Nairn, The Beginning of the End (New York: Verso, 1998), 39.

5. John Barnicoat, Posters, a Concise History (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1985), 244-245, and Gene M. Tempest, “Anti-Nazism and the Ateliers Populaires: The Memory of Nazi Collaboration in the Posters of Mai ’68,” thesis, published at http://www.docspopuli.org/articles/Paris1968_Tempest/AfficheParis1968_Tempest.html. Also see: Marc Rohan, Paris ’68 (London: Impact Books, 1988) and Michel Wlassikoff, The Story of Graphic Design in France (Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 2005), 224-227.

6. Atelier Populaire, Texts and Posters from the Revolution (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1969), iv.

7. Ibid.

8. Ross, 15-17.

9. See: EPICA Task Force, Nicaragua, A People’s Revolution (Washington D.C.: EPICA Task Force, 1980).

10. Sergio Ramírez, La Insurrección de las Paredes (Nicaragua: Editorial Nueva Nicaragua, 1984), 21. Translated in Armand Mattelart, ed., Communicating in Popular Nicaragua (New York: International General, 1986), 39.

11. Matelart, 11.

12. Ibid., 12.

13. Joel C. Sheesley & Wayne G. Bragg, Sandino in the Streets (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991), xxv.

14. Ibid., x.

15. Ibid., x.

16. Poster Book Collective, Images of Defiance, South African Resistance Posters of the 1980’s (Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1991), 14-15. See also: Julie Frederikse, South Africa, A Different Kind of War (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986).

17. Ibid., 3.

18. Judy Seidman, Red on Black: The Story of the South African Poster Movement (Johannesburg: STE Publishers, 2007), 71-75. See also: Diana Wylie, Art+Revolution: The Life and Death of Thami Mnyele (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press).

19. Posterbook Collective, 4-5.

20. See Posterbook Collective, as well as Gavin Younge, Art of the South African Townships (New York: Rizzoli International, 1988).

21. Posterbook Collective, 4-5.

22. Ibid., 2.

23. Sue Williamson, Resistance Art in South Africa (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989), 96-97.

24. Ibid., 93.

25. Ibid., 97.

26. Natasha Gordon & Paul Chatterton, Taking Back Control, A Journey Through Argentina’s Popular Uprising (Leeds: School of Geography, 2004).

27. Josh MacPhee, Stencil Pirates (Brooklyn: Soft Skull Press, 2004), 75-76.

28. Erick Lyle, “Colectivo Inconsciente,” in Josh MacPhee & Erik Reuland, eds., Realizing the Impossible: Art Against Authority (Oakland: AK Press, 2007), 84-85.

29. Taller Popular de Serigrafia, Trabajos 2002-2006, edición en processo (Buenos Aires: self published portfolio, 2006).

30. Unpublished interview between the author and Ryan Hollon.

31. Stuart Ewen, All Consuming Images (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 264.

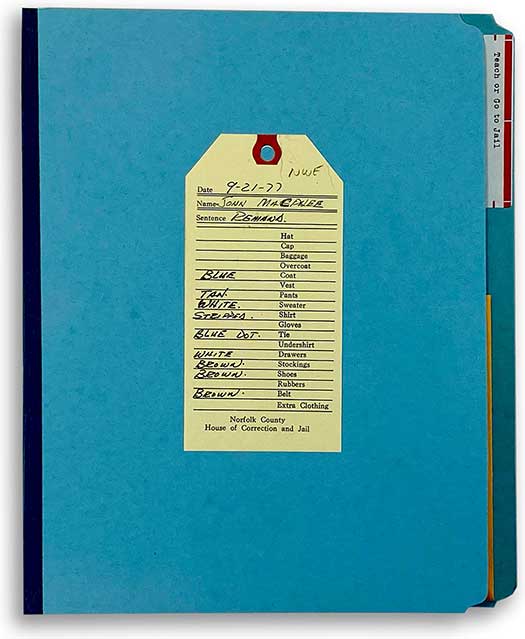

The images included in this post are taken from the following books, or received directly from the artists (in the case of Argentina):

Atelier Populaire, Texts and Posters from the Revolution (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1969).

Poster Book Collective, Images of Defiance, South African Resistance Posters of the 1980’s (Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1991), 14-15.

Sergio Ramírez, La Insurrección de las Paredes (Nicaragua: Editorial Nueva Nicaragua, 1984).

Joel C. Sheesley & Wayne G. Bragg, Sandino in the Streets (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991).

René Viénet, Enragés and Situationists in the Occupation Movement, France, May ’68 (New York: Autonomedia, 1992).

Sue Williamson, Resistance Art in South Africa (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989).

Thanks for sharing this great article. The three case studies are well developed to illustrate the integration of social struggles and street art, which is a history often not told very well. I agree wholeheartedly on the importance and potential to continue exposing and exploring these expressions.

Another part to be written elsewhere of particular interest to me would be how this is currently interwoven with the right to the city, how these expressions are controlled, banned, and challenged in urban settings across the world, and then how they are absorbed, copied, into mainstream art and media culture provoking new street demonstrations.

I’ll keep an eye around here for new updates and would love to receive any links to similar/related material exploring this issues in the future. And happy to reciprocate 🙂

Cheers,

Daniel

Hello Daniel

I am very impresed by your blog. I myself lifed in Nicaragua three years and was studing the Murales and the street art there. I even realised a book with the students from the UPOLI Managua. You can see some things on my blog http://www.bildlager.wordpress.com. There are some Stenciles I made with Sandino too.

I would like to get in touch with you to exchange a little about this subjet.

Saludos

Dominique

Congratulations on a well-structured, insightful piece. I am currently putting together a speech on street art and its role in society, focusing in on South Africa. If you have any extra links to information covering this topic, I would greatly appreciate it if you could email i to me.

Many thanks,

Natasha

An enlightened and refreshing piece on Art-social movements, bearing in mind the profound assertion of Stuart Ewen, how do we then as artists make collective use of today’s technology to bring about a more democratic society, by appealing and empowering the youth of today?

I can’t believe I came across this gem of an article to be followed by the positive comments from others. I am currently preparing my final portfolio for my Master’s in Library Science degree. Every project I completed in my courses directly related to Street Art and its dissemination to the masses. I hope to one day collect materials for a Street Art Library dedicated to this art movement. Thank you. AND good luck to others who in their own experiences with Street Art find ways to connect and to reach out to others.

an amazing insight

Loved the article – I have quoted it in my own blog.

cool! i’m going to translate the article into chinese!

I like your analysis and would like to quote you for an article. Could you let me know if I may, and how to get in touch? Thanks, kate

This is fascinating! Thank you for posting

An extremely interesting article, well-documented and well written ! I’m now working on the graffitis in revolutionary Egypt for a lecture and your article is really relevant, especially concerning the way art participates to the social movement, without being sufficient to impulse the revolutionary process (I think Proudhon also wrote about this, concerning art and revolution). Thank you for sharing !

We have posted a link to your article in our call for poster. It is very inspirative and I hope that this is ok. Thanks – J B L

HI This is a wonderful piece and I’d love to post parts of it on our website – partizaning. With a link to the original, ofcourse 😀