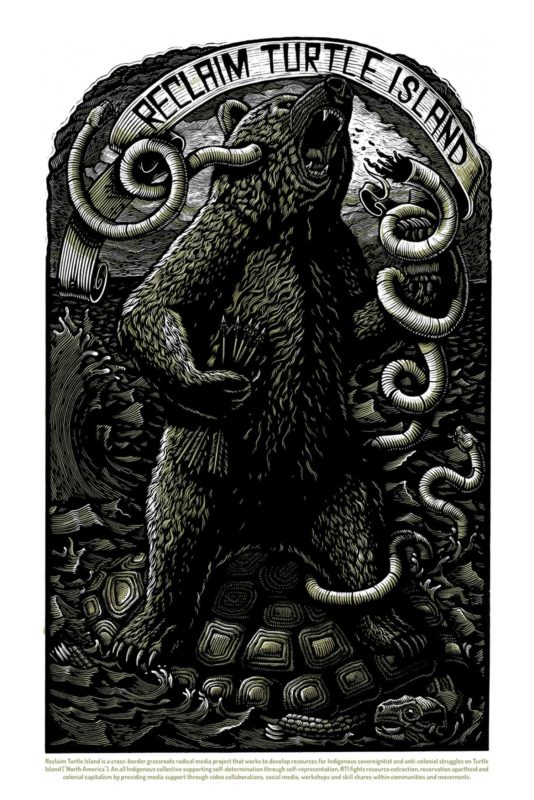

The Rough Road to San Juan Copala

Juan Copala, Oaxaca, at 9:20 the night of Monday, June 12. The name of

the Caravana, “Beti Cariño and Jyri Jaakkola”, is in honor of a strong,

much loved human rights defender who worked tirelessly for the

unification of the Triqui people, and of a comrade from Finland who

worked with the VOCAL organization on food sovereignty and climate

change projects, also much loved and appreciated for his stance of

solidarity. The two were murdered by the UBISORT paramilitary group led

by Rufino Juárez on April 27 of this year for daring to participate in

the first humanitarian caravan to the Autonomous Municipality. Their

motive? Breaking through a paramilitary siege that has forced 700

families to live without light, water, school, medical attention and

with very little food ever since last November 27.

Now the aim of the second caravan is the same, to break the siege. To

get into the Autonomous Municipality to deliver the supplies,

participate in an informational program on this dignified Triqui

community’s experience with self-government, to record testimonies of

human rights violations in a town where you can get shot any time you

step outside your door. A town where dozens of people have been killed

in recent months, including last May 20, when a commando of men

described as “non-indigenous” shot down Tleriberta Castro Aguilar and

her husband Timoteo Alejandro Ramírez, the natural leader and prime

mover of autonomy in San Juan Copala.

But killings and acts of violence go on every day in the country. What

made somewhere around 350 people decide to return to the scene of an

ambush, knowing that something similar could happen again? For the

people from San Juan Copala, it’s clear. Breaking the siege is a matter

of life and death. And it’s also a top priority for keeping the autonomy

project going.

For a lot of us, sick at our stomachs over so many outrageous abuses

where the perpetrators go scot-free, the April 27 ambush was kind of

like the attack on the Free Gaza fleet ––a moment when you say “things

aren’t going to go on this way,” especially when some of the comrades

hit hardest in the ambush immediately say “we have to go back into that

territory with a much bigger human rights caravan”.

http://contralinea.info/archivo-revista/index.php/2010/05/09/sobrevivir-a-la-emboscada/

A brief survey of some of the caravaners elicits different responses

about what led them to join in: “If I don’t go, what do I do with my

rage? How can just shoot down people who went there in peace!” “They’re

comrades. We have to stand by them”. “What kind of county do we live in

were the police themselves have to ask Rufino Juarez’s permission to go

into the area?” “I support what they’re doing in San Juan Copala. The

least we can do is take them some food. ” “We have to defend autonomy to

get rid of the parasites in the political class”. “So they can’t get

away with what they did.” “To break the siege.”

But whatever each person’s reason for going may be, everyone is

conscious of the risk. Some say they hope all the international support

will pressure Ulises Ruiz to call off his dogs, but it’s clear that any

one of us could die in San Juan Copala.

The previously announced press conference is not happening, at least not

with the right people, the Caravan organizers. Most reporters show a

decided preference for listening to speeches by Alejandro Encinas and

other PRD congresspersons, who’ve shown their intense concern for the

situation in San Juan Copala for a long time –at least two weeks. (See

“Legislators and San Juan Copala Residents Demand Dismantelment of

Paramilitary Group” http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2010/05/21/.) The racist

position of promoting the PRD House Coordinator as the top leader will

go on all during the Caravan. (See “Encinas Orders Return of

Humanitarian Caravan,” http://www.milenio.com/node/461188 .)

Even so, many of the free and independent media projects fight to bring

out what’s really happening. In an interview a couple of hours before

the departure of the Caravan, spokesperson Marcos Albino Ortiz expresses

his thanks for the support of student groups, social and professional

organizations, and congresspersons. When asked about the excessive

self-promotion of the legislators, which gives the impression that

they’re the Caravan organizers, Marcos responds that they’re present “in

solidarity and are not carrying their own banner”, and that the Caravan

is organized “by the people who are experiencing the violence of the

paramilitary siege in their own flesh and blood.” He stresses that the

safe arrival of the Caravan is a top priority and says: “We’re closely

watching its progress to see what the conditions are and to see whether

it will be able to go in or not.” He sends big hugs to all the people

who are planning solidarity actions on June 8 in Mexico City and

different parts of the world against the injustices against Triqui

people. He sends a message of thanks to the Other Campaign for its

support for autonomy from the left: “We can’t let San Juan Copala’s

autonomy be destroyed. We can’t bow down to State pressure and

intimidation.”

Another bus is added to the original 5; as of yet, this one carries only

a few people. As soon as we leave the city, the rules are read on each

bus and everyone signs a statement promising to respect the decisions

made by the Triqui Coordinating Committee, which knows the land and the

people better than anyone else. We then organize ourselves into brigades

of from 6 to 8 people to look out for each other.

Some of us sleep for a while before we get to Huajuapan de León at 6:30

in the morning, where we get a view of the crescent Moon in Aries in a

sky streaked with shades of rose, blue, and yellow, that get brighter as

the Sun comes up.

Comrades come in from the city of Oaxaca, Chiapas, Vera Cruz, Campeche,

and Guerrero. And our spirits are lifted by greetings from comrades

who’ll be protesting in Seattle, Portland, Boston, Vancouver, Barcelona,

Paris, and several cities in Greece, Italy, and Germany, among other

places.

While the brigades go out for breakfast, the Coordinating Commission

meets for a long time to evaluate the constantly changing situation.

Another press conference gets postponed. In view of a news flash about a

provocative action being organized by PRI party candidate Eviel Pérez

Magaña to “welcome” the Caravan to Juxtlahuaca, the route is modified in

order to avoid this kind of confrontation. The protection of the lives

of the people on the Caravan continues to be a top priority for the

organizers. More news of danger comes in, leading to a reconsideration

of whether or not conditions exist for the Caravan to proceed.

In the ongoing monitoring of the situation, reports are often

fragmentary, contradictory, and confusing. Thisproblem get even more

complicated when information and rumors are passed on by word of mouth.

As is the case in almost any situation, there are differences of opinion

over key issues. In spite of an overall distrust of the PRD due to its

betrayal of all the indigenous people of Mexico in 2001, among many

other things, some people insist that it would be impossible to advance

safely without the party’s presence. Other questions come up. Is it

true that Encinas has asked state and federal police to come in? How can

we possibly expect them to protect us after what they did in Oaxaca and

Atenco in 2006? Won’t they use it as a pretext to occupy the area?

At 10 o’clock, Commission members come out of their meeting. “Let’s go

to San Juan Copala!” We grab our things and get on the bus in high

spirits.

Now there are more than 400 of us, and we feel strong as we slowly move

ahead in 22 vehicles. At 1:08 in the afternoon, a convoy of from 12 to

15 state police patrol trucks and other vehicles of the supposedly

non-existent AFI and other police forces block the road going into

Juxtlahuaca.

The representatives of the Autonomous Municipality demand a guarantee of

safe passage for the Caravan to San Juan Copala from the Oaxaca State

Attorney General María de la Luz Candelaria Chiñas. But she’s not

interested in talking to them. She’d rather talk to the congresspersons.

She assures them that several different agencies are working on security

issues. She tells them that the Caravan will only be allowed to go on if

the leaders hand over the documents of all participants, a condition

that is rejected as a violation of the right of freedom of movement.

At 1:25, most of us get off the buses and start calmly walking ahead,

circumventing the police convoy. We’re all happy about making it clear

they haven’t been able to intimidate us. A couple of people suggest that

we could just keep on walking to Copala, carrying the supplies in with

us. When the police cars have to move on ahead of us, we get back on the

buses and go on to the town of Santa Rosa in the Mixteca Region. From

this time on, most of us don’t get much information about the

negotiations due to security considerations. A lot of the following

details only came out in subsequent conversations or reports.

At Santa Rosa there are more talks with the Attorney General. To make it

short, she assures Alejandro Encinas that freedom of movement exists in

Oaxaca, but the government can’t guarantee it.

She says that Oaxaca state police agents and those of the AFI (that

doesn’t exist), SSP, PFP, PGR, public prosecutors, human rights

officials, and state legislators are all here to provide safety for the

Caravan, but that there is no way to give “a 100% guarantee that there

will be no problems.” And why is this? Ahhh, of course. It’s because the

government simply “has no control” over these “violent Triquis” or over

“historic problems” between the MULTI, UBISORT and MULT organizations.

She washes her hands of the matter: “The government is not responsible

for any act of provocation between them.”

Candelaria Chiñas has several suggestions, including one that UBISORT

should stand guard over the Caravan, another that UBISORT should

participate in the negotiations in Juxtlahuaca, and still another that

the Caravan should hand over part of the food and medical supplies to

UBISORT ––conditions that are obviously an insult to the Autonomous

Municipality. And where do these original ideas come from? Well, if

truth be told, they’re demands made by Rufino Juárez, who doesn’t even

blush about dictating the terms of the “dialogue”.

Doctor Adrian Ramirez, President of the Mexican Human Rights League,

LIMEDDH, asks how it’s possible that you officials have dealings with

“somebody accused of serious crimes that you can’t even control!”

Once again, Marcos Albino and Omar Esparza demand that the authorities

investigate the murders in the first caravan and that they guarantee the

entry of the Caravan.

Another of Rufino Juárez’s messengers, the President of the State Human

Rights Commission, Heriberto Antonio García, states that there are

Triquis who oppose the entry of the Caravan. “Rufino Juarez is there a

little further on with a group of people….and we think there could be

some kind of conflict.” He assures everyone that “they want dialogue.

We’ve urged them to allow passage of the Caravan without any

obstructions… but they’ve been totally clear about the fact that it is

not convenient for the Caravan to enter right now.”

In other words, UBISORT’s word is law. Has the State created a monster

it can’t control? Or is it just that it’s not to its advantage to

control it right now?

As the Caravan gets into the Triqui Region, the nature of the police

operation changes. Now hundreds of state and federal police not only

ride around in pickups. They take up positions at every 50 to 100 yards

on the ridges, slopes, and other strategic points with their assault

rifles pointed at the Caravan. Are they the police? Military troops?

Militarized police? Policified troops? Paramilitaries? Parapolice? How

can we tell? They all look alike and act the same way.

“They aren’t there for UBISORT”, says one comrade. “They’re there for us.”

From this point on, no one is allowed to get off the bus under any

circumstances. Several of us try to document the operation from inside.

There are more talks in Agua Fría, a new evaluation, and another

decision to proceed with caution. When we get to a rise called Diamante

approaching La Sabana, the police offer to take a congressmen and,

apparently, a human rights defender to verify whether or not UBISORT has

blocked the road. They find that a row of UBISORT paramilitaries are

backing up a row of women and children from their organization at the

entrance to San Juan Copala ––an astute tactic to make it seem in the

press that the Caravan is against indigenous women and children.

Around 5 o’clock in the afternoon, it’s reported on the buses that

“there were gunshots,” that “security conditions do not exist for the

Caravan to advance,” and that “we will return to Huajuapan.” Mission

aborted. Many of us strongly disagree with the decision and think that

by turning back now, we’re losing our best chance to go into Copala and

break the siege. We think the mood of people willing to go in despite

the risk is a key factor. The Commission considers what we say, but

sticks to their decision. They don’t want to risk the life of a single

person.

That night, there’s an event at the Flamingos meeting hall, where Jorge

Albino and Omar Esparza call for intensifying national and international

pressure to break the siege around San Juan Copala. Given the complicity

of the State with the paramilitaries, they plan to rely on international

bodies like the Red Cross to deliver the supplies. If this doesn’t work,

there’s a proposal for a women’s caravan to try once more to break the

siege.

After the event, there’s a march and rally in the streets of Huajuapan,

and the next day, more talks and evaluations in the city. There’s also a

march the next day in the city of Oaxaca, with a contingent supporting

San Juan Copala. On Thurday, June 9, the Caravan is welcomed in the

Mexico City Zócalo with hugs, smiles, a tear or two, and a lot of

reflection about how to move ahead on the road to autonomy ––the road to

San Juan Copala.

x Carolina

————————————————————–

(Español)

El accidentado camino a San Juan Copala

Seis autobuses, varios coches y camionetas, y un trailer repleto de 35

toneladas de víveres salieron del Zócalo de la Ciudad de México, rumbo

al Municipio Autónomo de San Juan Copala, Oaxaca, a las 9:20 de la noche

del lunes, 7 de junio. La Caravana llevaba el nombre “Beti Cariño y Jyri

Jaakkola” en honor de una fuerte y querida defensora de derechos humanos

que trabajaba incansablemente para lograr la unificación del pueblo

triqui, y de un compañero finlandés que colaboraba con la organización

VOCAL en los proyectos de soberanía alimentaria y cambio climático,

muy querido y apreciado por su postura solidaria. Los dos fueron

asesinados por el grupo paramilitar UBISORT, dirigido por Rufino Juárez,

el 27 de abril de este año por haberse atrevido a participar en una

primera caravana humanitaria al mismo Municipio Autónomo. ¿Su motivo?

Romper el sitio paramilitar que obliga a 700 familias a vivir sin luz,

agua, escuela, atención médica y con muy poca comida desde el pasado 27

de noviembre.

De nuevo, la expectativa de la segunda caravana es romper el cerco.

Entrar en el Municipio Autónomo para entregar las toneladas de acopio,

realizar un programa informativo sobre la experiencia del auto-gobierno

de esta digna comunidad triqui y tomar testimonios sobre las violaciones

de derechos humanos en un municipio donde cada día hay riesgo de ser

baleado si sales de tu casa. Un municipio donde decenas de personas han

sido asesinadas en los últimos meses, incluso el pasado 20 de mayo

cuando un comando de gente descrita como “no-indígena” acribilló a

Tleriberta Castro Aguilar y su esposo Timoteo Alejandro Ramírez, líder

natural e impulsor de la autonomía en San Juan Copala.

Pero diariamente hay asesinatos y actos de violencia en el país. ¿De

dónde surge la decisión de unas 350 personas de regresar a la escena de

una emboscada, sabiendo que algo parecido podría volver a pasar? Para

los habitantes y familiares de San Juan Copala, está claro. Romper el

cerco es asunto de vida o muerte. Y también es un asunto primordial para

su proyecto de autonomía.

Para varios de nosotros, asqueados de tantos atropellos y tanta

impunidad, la emboscada del 27 de abril fue un poco como el ataque

contra la flotilla “Libertad para Gaza” –– un momento para decir “esto

no puede quedar así”, especialmente cuando unos de los compas más

afectados no dudaron en decir “Hay que regresar al territorio con una

caravana de derechos humanos más grande”.

http://contralinea.info/archivo-revista/index.php/2010/05/09/sobrevivir-a-la-emboscada/

Una breve encuesta a las y los varios caravaneros revela distintos

motivos por su decisión de participar: “Si no voy ¿qué hago con mi

coraje? Cómo es posible que balacearon a gente que andaba en plan de

paz.” “Son compas. Hay que estar con ellos”. “¿En qué país vivimos

cuando hasta los mismos policías tienen que pedirle permiso a Rufino

Juárez para entrar en la zona?” “Apoyo lo que están haciendo en San Juan

Copala. Lo menos que podemos hacer es llevarles comida”. “Hay que

defender la autonomía para acabar con los parásitos de la clase

política”. “A acabar con la impunidad”. “A romper el cerco”.

Pero sea cual sea el motivo para meterse en la Caravana, todos y todas

están conscientes de los riesgos. Aunque algunos expresan la esperanza

de que el fuerte apoyo internacional pueda presionar a Ulises Ruiz a

controlar sus perros, todos saben que cualquiera de nosotros puede morir

en San Juan Copala.

La conferencia de prensa previamente anunciada no ocurre, por lo menos

no con las personas apropiadas, es decir con los organizadores de la

Caravana. La mayoría de los medios muestran su clara preferencia para

escuchar los discursos de Alejandro Encinas y los diputados del PRD,

quienes ya han mostrado su intensa preocupación por la situación de San

Juan Copala durante mucho tiempo ––por lo menos durante un par de

semanas. (Vean: “Legisladores y habitantes de San Juan Copala exigen

disolución de grupo paramilitar”,

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2010/05/21/.) La postura racista de

promover al Coordinador del PRD como el líder se mantiene a cada paso de

la caravana. (Vean: “Ordena Encinas regreso de la caravana humanitaria”

http://www.milenio.com/node/461188 .)

Sin embargo, muchos de los medios libres y uno u otro proyecto

independiente dan la batalla para representar lo que realmente está

pasando. Un par de horas antes de la salida de la Caravana, en una

entrevista con los medios libres, el vocero Marcos Albino Ortiz agradece

el apoyo de los grupos de estudiantes, organizaciones sociales,

profesionistas y de un grupo de diputados. Al ser preguntado sobre el

excesivo protagonismo de los diputados que hace parecer que ellos mismos

están organizando la Caravana, el compañero Marcos responde que ellos

“van en solidaridad y no llevan ninguna bandera”, y que la Caravana se

organiza “por el pueblo, por la gente que siente en carne propia lo que

es vivir en la violencia, cercado por los paramilitares”. Enfatiza que

la segura llegada de la Caravana es una alta prioridad y dice: “Vamos a

estar pendientes de su avance para ver qué condiciones hay, si puede

entrar o no puede entrar”. Envía un fuerte abrazo a toda la gente que

planean actos de solidaridad para el día 8 en el DF y en varias partes

del mundo contra las injusticias cometidas contra la población triqui.

Envía un mensaje de agradecimiento a La Otra Campaña por su apoyo a la

autonomía desde la izquierda: “No podemos dejar caer la autonomía de San

Juan Copala. No podemos caernos de rodilla ante las presiones y las

intimidaciones que nos está enviando el gobierno del estado”.

A los 5 autobuses mencionados en la entrevista, se añade otro, éste con

poca gente. Apenas salimos de la ciudad, se leen las reglas del viaje y

cada persona firma una hoja prometiendo respetar las decisiones tomadas

por la Comisión Coordinadora Triqui que conoce más que nadie el terreno

y la gente. Luego nos organizamos en brigadas de seis u ocho personas

para propósitos de seguridad.

Algunos dormimos un rato antes de llegar a Huajuapan de León a las 6:30

de la mañana, donde apreciamos una Luna creciente en Aries en un cielo

con colores de rosa, azul y amarillo que se ponen más intensos con la

salida del Sol.

Llegan compañeras y compañeros de la ciudad de Oaxaca, Chiapas, Vera

Cruz, Campeche y Guerrero. Y los ánimos suben al recibir saludos de

compañeros protestando en Seattle, Portland, Boston, Vancouver,

Barcelona, Paris y varias ciudades en Grecia, Italia y Alemania, entre

otros lugares.

Mientras salimos en brigadas a desayunar, la comisión coordinadora se

reúne durante un buen rato para evaluar los cambios constantes en la

situación. Por eso, otra conferencia de prensa se pospone. En vista de

la noticia sobre una provocación montada por el candidato priista Eviel

Pérez Magaña en Juxtlahuaca para “recibir” a la Caravana, la ruta se

modifica para evitar un enfrentamiento directo de este tipo. La

protección de las vidas de los participantes sigue siendo de alta

importancia para los organizadores. Hay otras indicaciones de peligro

que provocan un análisis sobre la cuestión de que si existen las

condiciones para el avance de la Caravana o no.

Hay constante monitoreo de la situación en la zona, aunque a veces los

informes son fragmentarios, contradictorios y confusos. Este problema se

complica más en la transmisión de las noticias de boca en boca. Como

sería natural en cualquier situación, hay diferencias de opinión sobre

varios aspectos claves. A pesar de la desconfianza generalizada en el

PRD debido a su traición a todos los indígenas de México en el 2001,

entre otras cosas, hay quienes insisten en que sería imposible avanzar

sin su presencia. Otras dudas surgen. ¿Es cierto que Encinas ha pedido

la intervención de la policía estatal y federal? ¿Cómo es posible

esperar protección de ellos después de su actuación en Oaxaca y Atenco

en el 2006? ¿No utilizarán esto como pretexto para ocupar la zona?

A las 10 de la mañana, la comisión concluye su reunión. “¡Vamos a San

Juan Copala!” Agarramos las cosas y subimos a los camiones con muchas

ganas.

Ahora somos más de 400 personas que avanzamos lentamente en 22 vehículos

y nos sentimos muy fuertes. A la 1:08 pm un convoy de 12-15 patrullas de

la policía estatal y varios otros vehículos de la AFI y otras agencias

policiales bloquean el camino en la entrada a Juxtlahuaca.

Los representantes del Municipio Autónomo exigen a la procuradora

estatal María de la Luz Candelaria Chiñas una garantía del paso seguro

de la Caravana a San Juan Copala. Pero ella no tiene interés en hablar

con ellos. Prefiere hablar con los diputados. Les asegura que varias

agencias están trabajando para brindar seguridad. Afirma que la Caravana

sólo puede pasar si los líderes muestran todos los documentos de lo

integrantes, una condición que es rechazada por ser una violación a la

libertad de tránsito.

A la 1:25 pm, la mayoría bajamos de los camiones y empezamos a caminar

tranquilamente, eludiendo el convoy policial. Todos estamos muy felices

por dejar en claro que no han logrado intimidarnos. Un par de personas

piensan que tal vez podemos llegar caminando a Copala, cargando los

víveres. Cuando los policías se ven obligados a avanzar, subimos de

nuevo a los autobuses y avanzamos hasta Santa Rosa en la región mixteca.

De ahora en adelante la mayoría de los caravaneros no recibimos mucha

información sobre las negociaciones por cuestiones de seguridad. Muchos

de los detalles que siguen solo se saben de informes o de pláticas

posteriores.

En Santa Rosa hay más pláticas con la procuradora. En breve, ella le

asegura a Alberto Encinas que “hay libre tránsito en Oaxaca” pero que el

gobierno es incapaz de garantizarlo.

Dice que hay agentes estatales y de la (supuestamente inexistente )

AFI, SSP, PFP, PGR, ministerios públicos, oficiales de derechos humanos

y diputados estatales presentes para brindar seguridad a la Caravana,

pero que no hay manera de dar “una garantía al 100% que no vaya a

haber problemas”. Y eso ¿por qué? Ahhh, claro, porque el gobierno “no

tiene control” sobre esos “violentos triquis” o sobre “los problemas

históricos” entre el MULTI, UBISORT y MULT. La procuradora se lava las

manos: “El gobierno no es responsable de un acto de provocación entre

ellos”.

Candelaria Chiñas tiene varias sugerencias, incluso que la Caravana vaya

acompañada por la UBISORT, o que la UBISORT participe en una reunión en

Juxtlahuaca, o que la Caravana entrega una parte de su acopio al

UBISORT– unas condiciones que obviamente son un insulto al Municipio

Autónomo. ¿Y de dónde vienen estas ideas tan originales? Pues, son las

demandas del mismo Rufino Juárez, quien ni se ruboriza al dictar los

términos del “diálogo”.

El doctor Adrian Ramírez, Presidente de la Liga Mexicana de Derechos

Humanos, LIMEDDH, pregunta ¡¿cómo es posible que han citado “una persona

señalada en una averiguación previa y que ustedes no sean capaces de

controlarlo”!?

Los compañeros Marcos Albino y Omar Esparza repiten las demandas: que

las autoridades investiguen los asesinatos de la primera caravana y que

“brinden las garantías para que entre nuestra Caravana”.

Otro mensajero de Rufino Juárez, el Presidente de la Comisión Estatal de

Derechos Humanos, Heriberto Antonio García, afirma que hay triquis que

piden que la Caravana no ingrese. “Rufino Juarez está más adelante con

un grupo de personas…. y pensamos que podría haber algún conflicto”.

Asegura que “ellos quieren dialogar. Nosotros les hemos exhortado a que

le permitan el tránsito de la caravana y que no la obstaculicen…. pero

ellos han manifestado de una manera clara y determinante que este

momento no es conveniente que ingresen”.

Es decir, la palabra de UBISORT es la ley. ¿El Estado ha creado un

monstruo que no puede controlar? o ¿No le conviene controlarlo en este

momento?

Al entrar en la región triqui, la naturaleza del operativo policial

cambia. Ahora cientos de agentes estatales y federales no sólo andan en

camionetas, sino que asumen posiciones a cada 50 o 100 metros encima de

los cerros o en otros lugares estratégicos con sus rifles de asalto

entrenados sobre la Caravana. ¿Son policías? ¿Militares? ¿Policías

militarizados? ¿Militares-policiacas? ¿Paramilitares? ¿Parapoliciales?

¿Cómo saber? Todos se ven iguales y hacen lo mismo.

“Ellos no están aquí para vigilar a la UBISORT”, comentó un compañero.

“Su tarea es controlarnos a nosotros”.

De ahora en adelante está estrictamente prohibido bajar del camión.

Varios intentamos registrar el operativo desde el autobús.

Hay más pláticas en Agua Fría, una nueva evaluación y una decisión de

proceder con cautela. Al llegar al punto Diamante cercana a La Sabana,

la policía ofrece llevar a un diputado y, al parecer, un defensor de

derechos humanos a averiguar si la UBISORT tiene el camino bloqueado.

Averiguan que una fila de paramilitares de la UBISORT respalda una

fila de mujeres, niñas y niños de su organización en la entrada de San

Juan Copala ––una táctica muy astuta para dar la impresión en la prensa

de que la Caravana está en contra de las mujeres, niños y niñas indígenas.

Alrededor de las 5:00 de la tarde, se reporta en los autobuses que

“hubo balazos”, que “no hay condiciones de seguridad para proceder” y

que “regresaremos a Huajuapan”. Misión abortada. Hay mucha

inconformidad con esta decisión entre varios compañeros que sentimos que

el desistir ahora es perder una gran oportunidad de entrar en Copala y

romper el cerco. Un factor importante para nosotros es el estado de

ánimo de la gente dispuesta a entrar a pesar del riesgo. La comisión del

Municipio Autónomo considera lo que planteamos, pero reafirma su

decisión. No quiere arriesgarse a que una sola persona muera.

En la noche, hay un evento en el Salón Flamingos donde los compañeros

Jorge Albino y Omar Esparza reiteran su compromiso para intensificar la

presión nacional e internacional para romper el cerco alrededor de San

Juan Copala. Dada la complicidad total entre el Estado y los

paramilitares, piensan acudir a las instancias internacionales, como la

Cruz Roja para lograr la entrega del acopio. En el evento que esto no

sea posible, hay una propuesta para que una caravana de mujeres intente

romper el cerco de nuevo.

Después del evento hay una marcha y mitin en las calles de Huajuapan, y

el próximo día más pláticas y evaluaciones en esta ciudad. También hay

una marcha en la ciudad de Oaxaca con presencia de San Juan Copala. El

jueves, 9 de junio, la Caravana se recibe en el Zócalo de la Ciudad de

México con abrazos, sonrisas, una y otra lágrima y muchas reflexiones

sobre cómo navegar el accidentado camino a la autonomía –el camino a San

Juan Copala.

x Carolina