Last install (here) I shared five covers from books published by small African presses. Turns out my collection is a little bigger than I thought, with way more books than makes sense to squeeze into only one or two posts. So I’m going to break these covers down by region: West Africa, East Africa, and Southern Africa. This week I’ll start with West Africa.

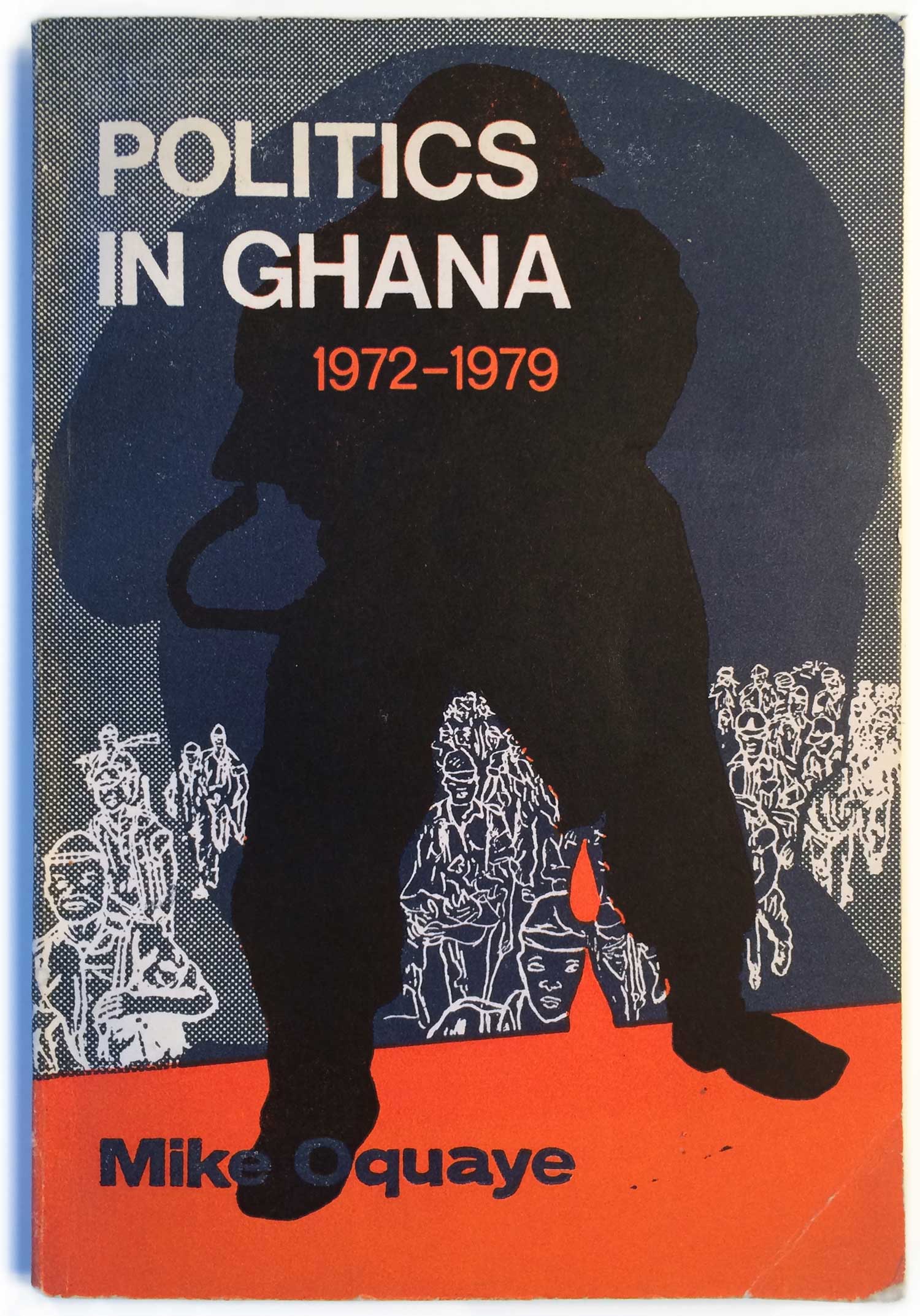

The first one is Mike Oquaye’s Politics in Ghana 1972–1979, published in 1980 by Tornado Publications in Accra. Like most of these presses, there is very little information available about them, online or otherwise. It appears that Tornado might be a personal press of Oquaye’s, as the only other book I see reference to is also by him. In terms of cover design, this book has all the elements I love about the aesthetics of “Third World publishing”—spot color printing, poorly trapped registration, and a strong combination of flat graphic and illustrative qualities. The orange background and blue military silhouette merge into a black, brutalist soldier, his gun dripping orange blood which creates the ground he stands on.

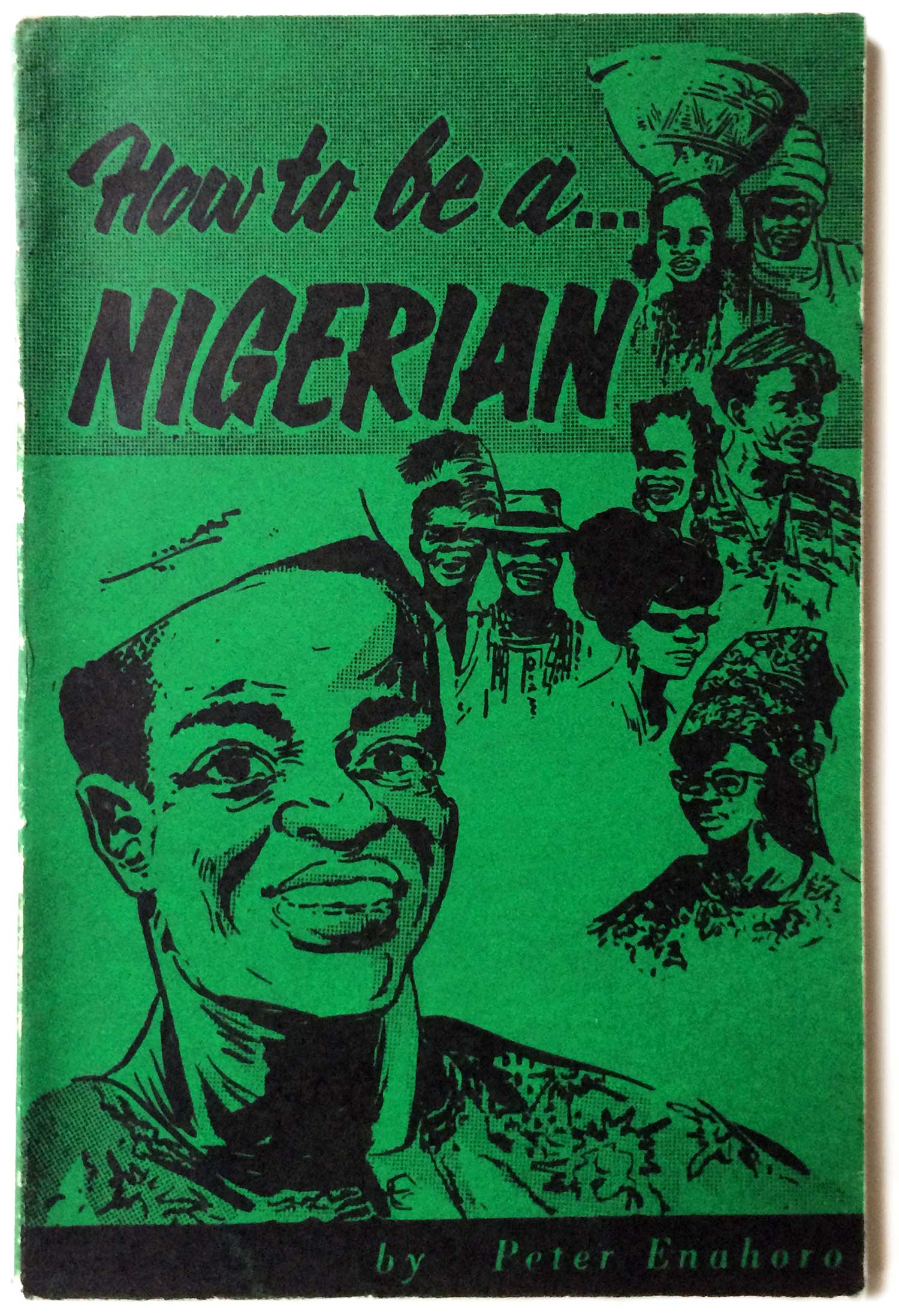

The above title aside, in the realm of publishing “West Africa” largely means Nigeria, which towers over the rest of the region. I have featured presses from other countries (Cameroon & Ghana) here in the past, but there is no question that Nigeria is the publishing powerhouse with dozens of presses, small and large. The following six titles are from five different Nigerian presses, most of them from Southeast Nigeria (Ibadan and Port Harcourt). First is Peter Enahoro’s How to Be a Nigerian, a book-length riff on Onitsha Market pamphlets. Onitsha Market literature emerged out of Onitsha—the largest market in Africa—in the 1950s and flourished in the 60s. Mostly in pamphlet form, this literature was a mix of self-help, rudimentary history, popular stories, and aphorisms, all written in a mix of standard and pidgin English. Thousands of these pamphlets were produced, hung on clotheslines in front of stalls and sold for pennies. They were roughly produced on letter-presses, and many were extremely popular, with multiple print runs. How to Be a Nigerian appears to be an attempt to capitalize on this popularity. Enahoro was the writer of a popular column in the Daily Times of Nigeria, and this is a humorous take on what it means to be Nigerian in the mid-1960s. The drawings by Chuks Anyanwu are much more refined than those in Market Lit., and are more like the Nigerian version of 1950s editorial cartoons. The copy I have is the eighth printing, with a simple green and black cover. For more information on Onitsha Market literature, check out Kurt Thometz’ excellent Life Turns Man Up and Down (Pantheon, 2001).

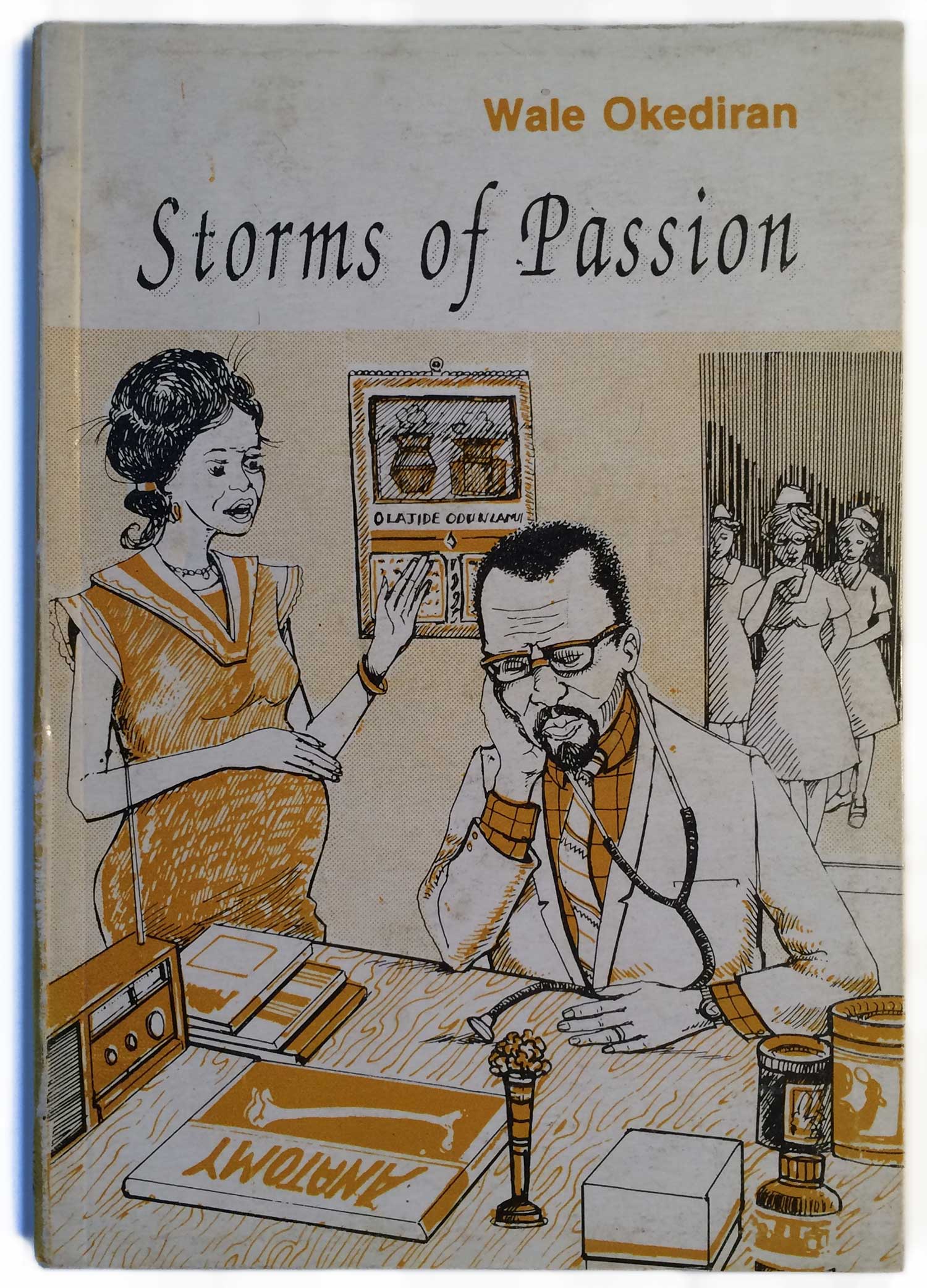

In a different way, Wale Okediran’s Storms of Passion is also a descendant of Onitsha lit. It’s an easy reading mix of moral tale and romance novel. The cover is a great comic drawing of the main doctor character, his hectoring wife, and the cute nurses waiting in the wings. It’s cheaply produced, the duotone image printed on the coated side of a cover sheet made of rough cardstock, and the insides printed on thin, acidic paper. The publisher, the Evans Brothers, appears to still be in business, and largely publishes for the educational market. Their one of the few African publishers I’ve found that has a website.

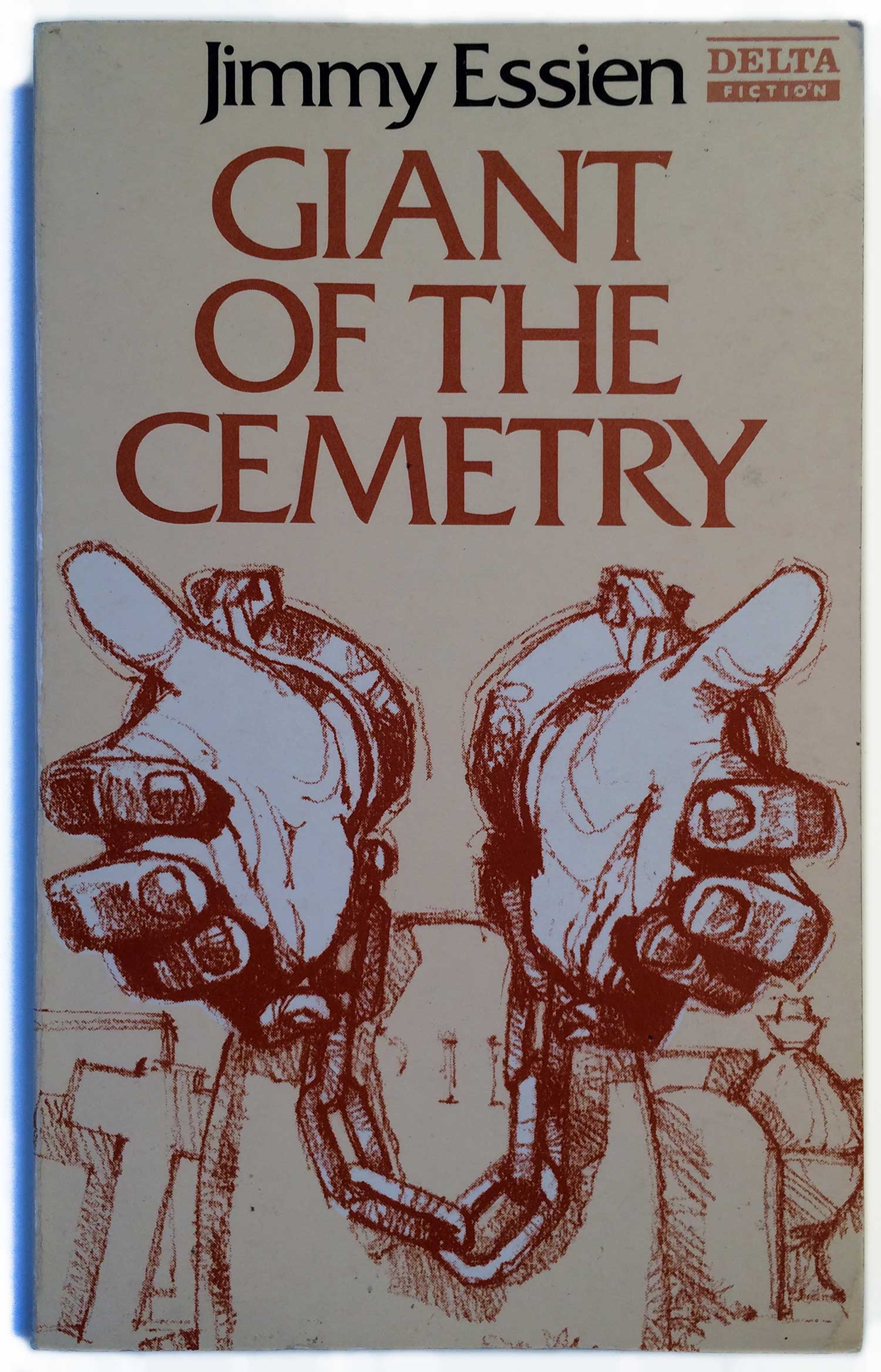

I found a copy of Giant of the Cemetry in the basement of a bookstore in Pittsburgh, lurking with all the other random fiction. It’s odd for an African book, with the trim size and general look and feel of an American or UK mass-market novel. Although the publisher is Nigerian (From Enugu State in the Southeast, about an hour from the above discussed Onitsha Market), the book was type-set in the Philippines and printed in the UK—and has higher production values than much African book output. Delta appears to still exist, but doesn’t have a website. They were the publishers of Chris Abani’s first novel, Masters of the Board, in 1985. (For those that haven’t yet, pick up a copy of Abani’s Graceland or The Secret History of Las Vegas, both are great reads!). Giant of the Cemetry‘s rough hewn cover illustration at first doesn’t seem up to the job, but it actually works quite nice, printed in sepia on a light peach background. The slight tonal variation of the white behind the hands makes them jump out, and the chains and tombstones give the entire thing a bit of a old-timey horror feel. Maybe not appropriate for a political thriller about an African revolution, but on a purely aesthetic level it work.

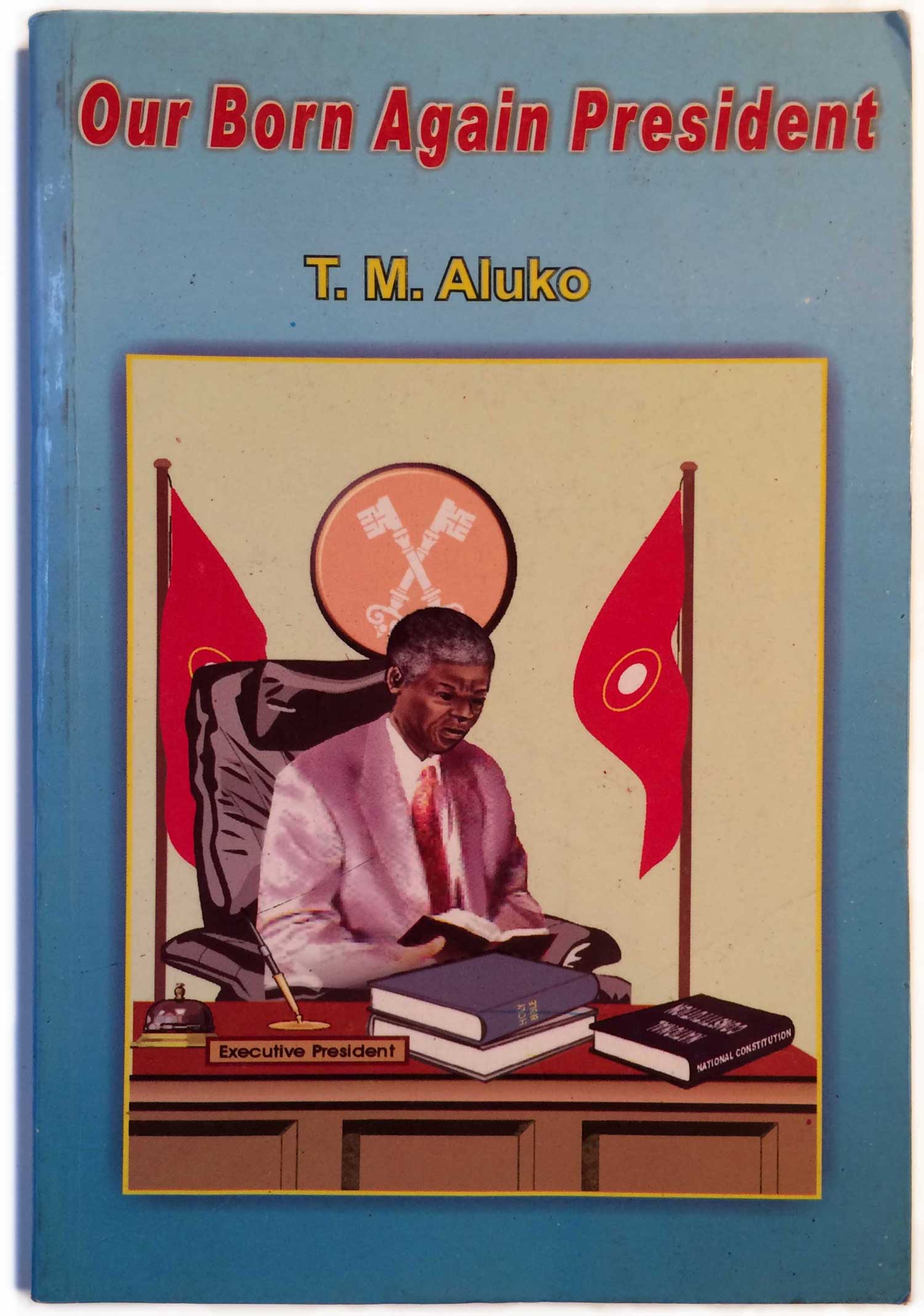

T.M. Aluko (1918–2010) was one of Nigeria’s first wave of post-independence writers, along with Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Cyprian Ekwensi. Unlike the others—who are all Igbo and developed their writing and ideas in Ibadan—Aluko was Yoruba, and worked most of his life in the civil service of the Nigerian Government. He wrote around a dozen novels and memoirs, including five that were published as part of the Heinemann African Writers Series. This book, Our Born Again President, is his final novel, published in 2009. Like most of his books, it is a satirical take on Nigerian government and society. It was published by HEBN Publishers, what became of Heinemann in Nigeria when it came under complete African ownership. HEBN is still Nigeria’s leading educational press, and has an active publishing schedule and pretty robust website (including a music video called “Happy Hour” featuring the entire HEBN staff dancing around their office!). Our Born Again President is part of the Frontline Series of novels, and has a fully digitally produced cover, with a computerized version of a vernacular drawing, with outlined and shadowed fonts and boxes. There’s a certain beauty to covers like this, a “outsider” design style.

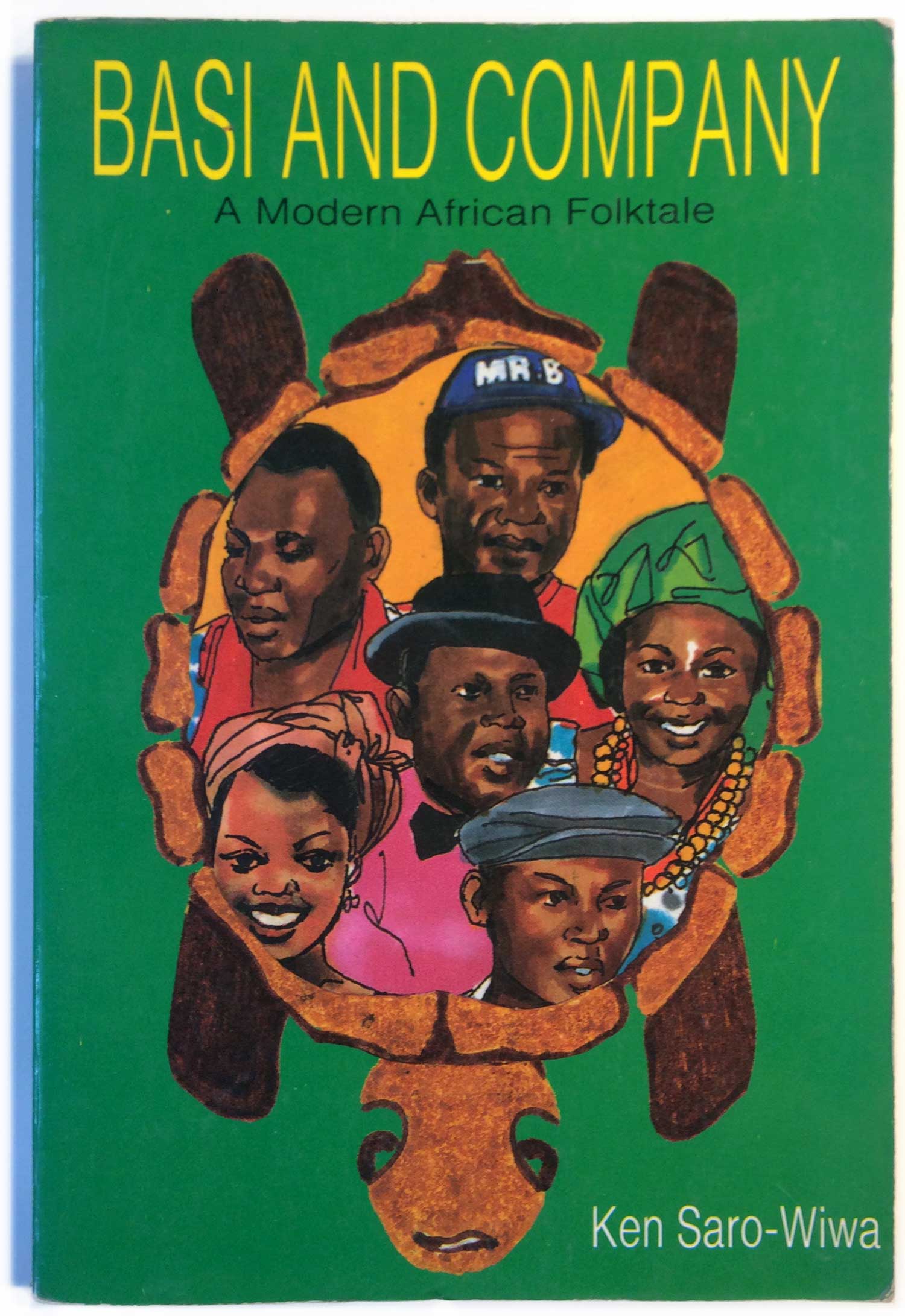

The last two books this week are by Ken Saro-Wiwa, published on his own SAROS Press. Saro-Wiwa was a writer, politician, businessman, and activist from Ogoniland in Southern Nigeria. Outside of Nigeria is is most known as the president and spokesman for the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), a nonviolent environmental group fighting against Shell and other oil companies destroying Ogoniland in the Niger Delta. Saro-Wiwa was executed by the Nigerian government in 1995 after being falsely convicted by a military tribunal of the murder of pro-government Ogoni chiefs (even though he was no where near the murder scene). Within Nigeria Saro-Wiwa was largely known for his extremely popular television show, Basi and Company. Although from Southern Nigeria, Saro-Wiwa was not a supporter of the Biafran secession campaign in the 1960s, and rather than support Biafra and the Igbo, he argued that the real victims of the Nigerian Civil War were the non-Igbo minorities living in the south and caught between the Igbo Biafrian military and the Yuroba-dominated government. On a Darkling Plain is his telling of the Civil War, and is relatively unique in Nigeria literature, as most books are written from the Biafran perspective, including popular novels and titles by Chinua Achebe, Cyprian Ekwensi, and Buchi Emecheta. The cover shows Biafran soldiers (recognizable by the half sun patches sewn on their arms) as butchers, with bloody machetes. More recently, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’sHalf of a Yellow Sun is told from the Biafran perspective, but attempts to acknowledge and address the oppression of tribal minorities by both sides of the conflict. These SAROS titles are well produced, and Saro-Wiwa is an interesting writer. It’s unfortunate that almost all of his writing is now difficult to find, outside of his novel Sozaboy, the only one picked up by a larger publisher outside of Nigeria.

Next week we’ll look at small press African books from Eastern Africa, in particular Kenya.

This week’s bibliography: