The undisputed center of publishing in East Africa is Nairobi, the capital of Kenya. Kenya is home to the majority of the regions presses, and was a key center for the explosion of post-independence publishing in the late 1950s and 60s. The largest by far was the East African Publishing House (EAPH) which put out hundreds of titles, including their own “Modern African Writers” and “Modern African Poets” series, as well as multiple wings of youth publishing and both academic and non-academic non-fiction and history. But enough about EAPH, more on them in the future when I do a post series specifically about their output. Kenya is (or was) also home to Comb Books, Hienneman Kenya, Spear Books, and Uzima Press.

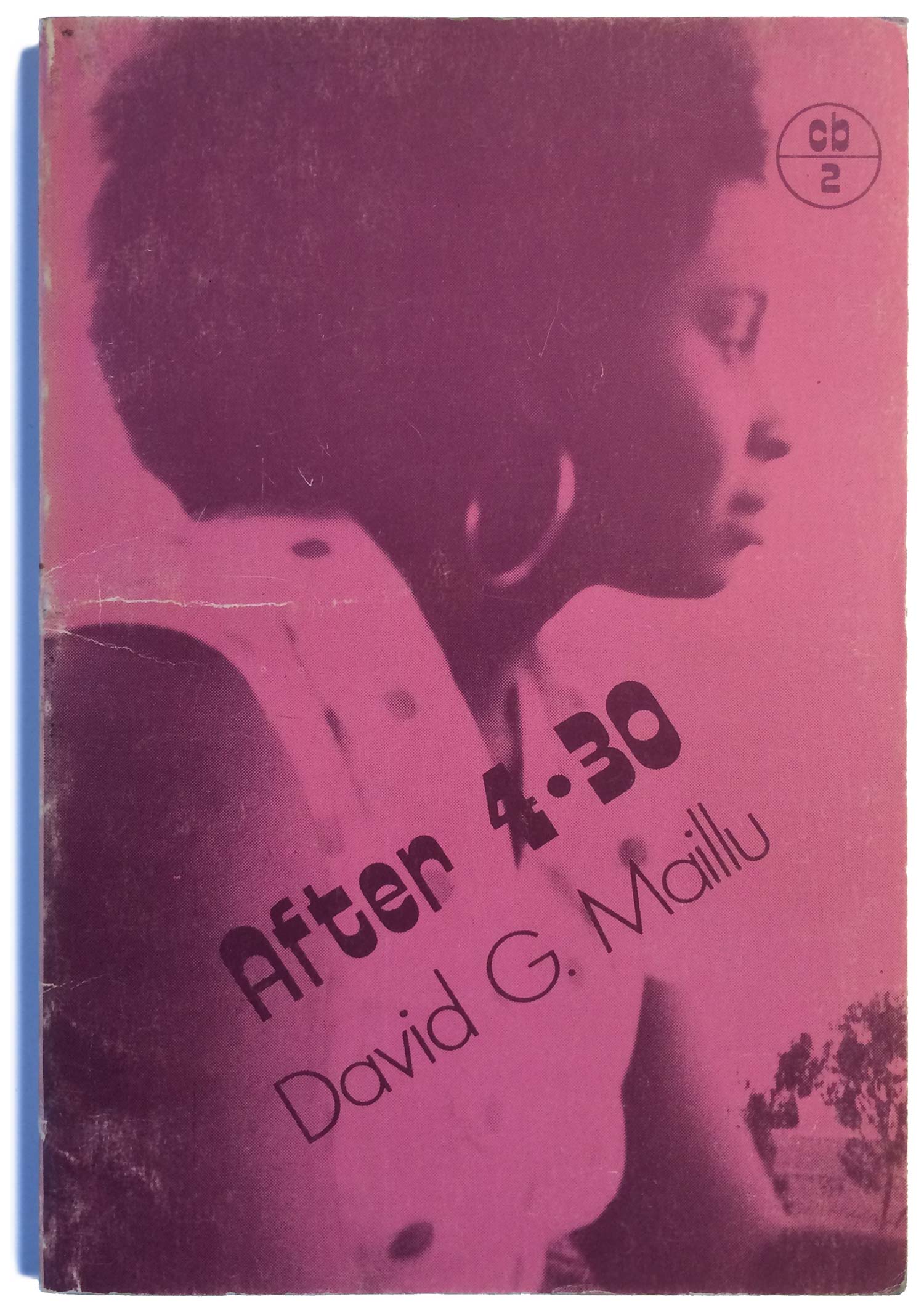

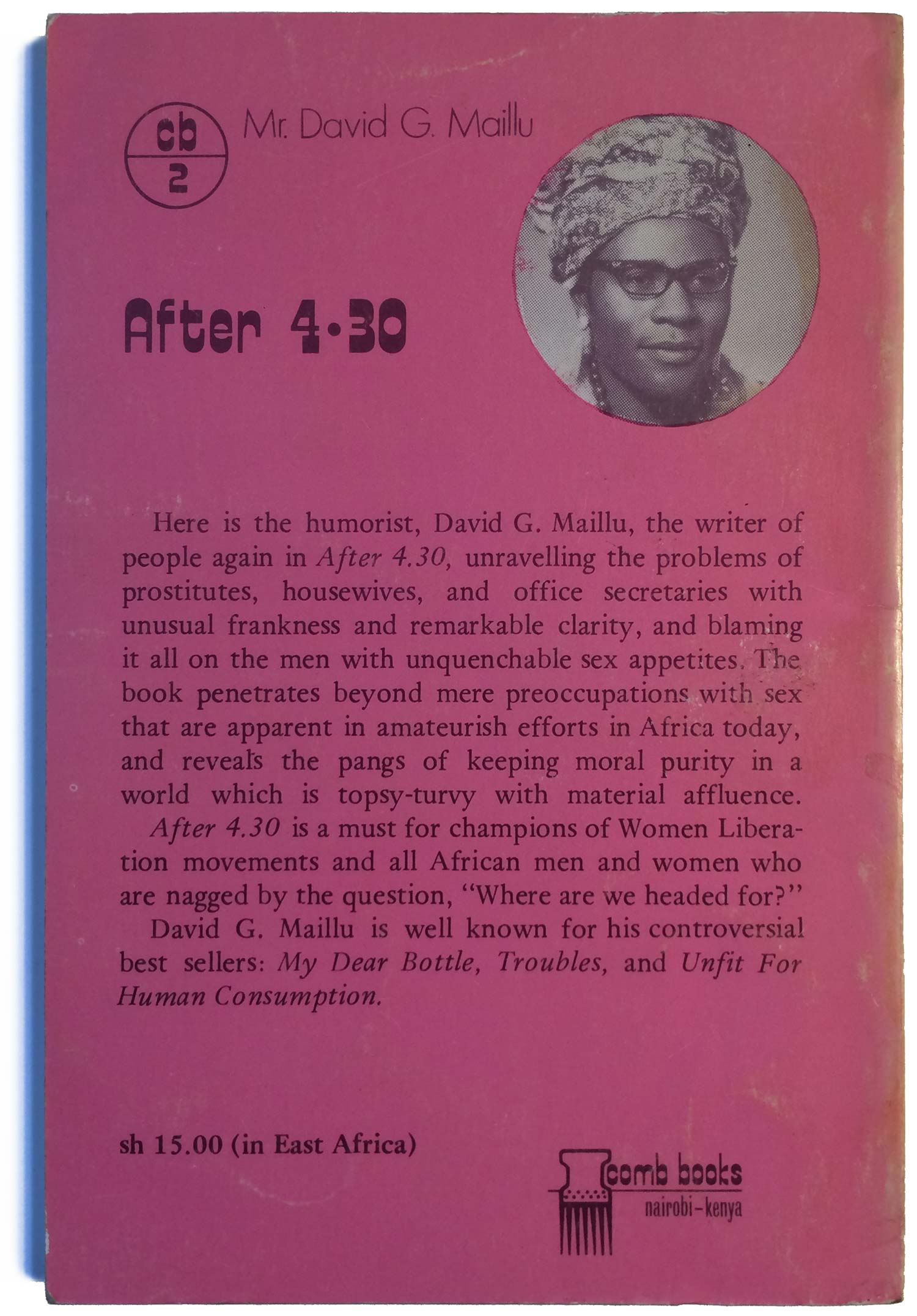

By far the hippest of the lot is Comb Books, with an awesome logo based on an afro-pick. I’ve only been able to find one title, the second published by Comb, David G. Maillu’s After 4:30. It’s a pseudo-feminist pop prose poem, a very strange thing! But the cover is cool as hell, purple halftone of a pink field, super 70s fonts running at a 45 degree angle to the fuzzy photo of an urbane African young woman. The branding is sharp, and the back cover features a nice inset author photo, clearly taking off from the convention used on Hienneman’s African Writers Series (as well as EAPH’s Modern African Writers). I found a small catalog for Comb in another book from Africa, which lists a half dozen titles, but I’ve never seen any of the others.

The big British educational publisher Heinemann was one of the biggest proponents of African literacy and writers in the post-colonial Anglo-African world. They had both distribution and editorial offices in a half dozen cities across the continent, and help develop a huge base of readers, writers, and editors. In the early 1980s they were caught up in the same crazy buying and selling spree of media entities that hit so many publishers. By the late 1980s the educational wing had been cleaved from the trade publishing company, and in-turn split in half, with independently owned companies in the UK and US. This corporate shake-up meant that the African offices were all jettisoned, but a couple were able to regroup and continue under local control and ownership. Back in JBbTC 226 I discussed the Nigerian Hienemann, and now we can look at the Kenyan.

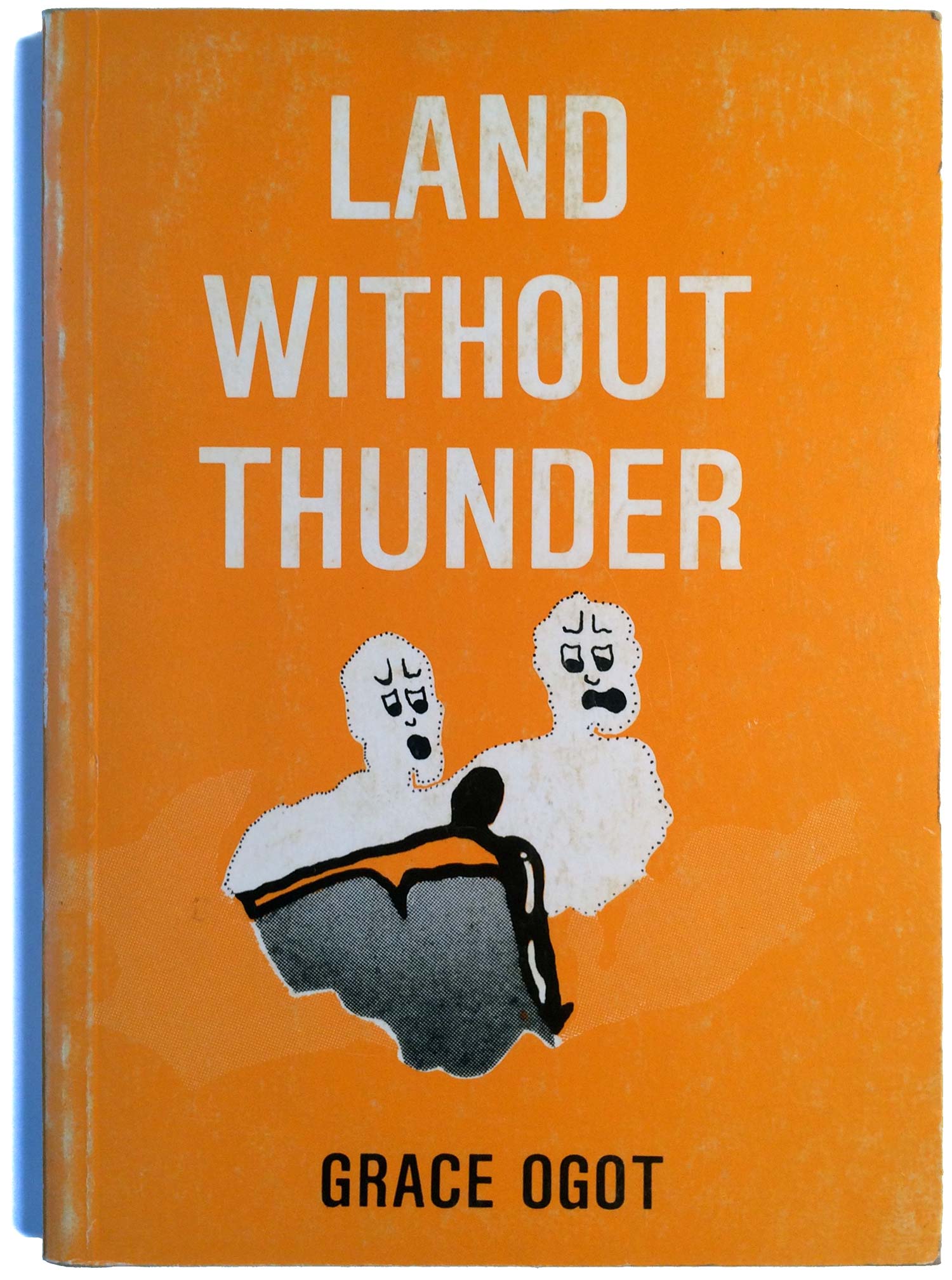

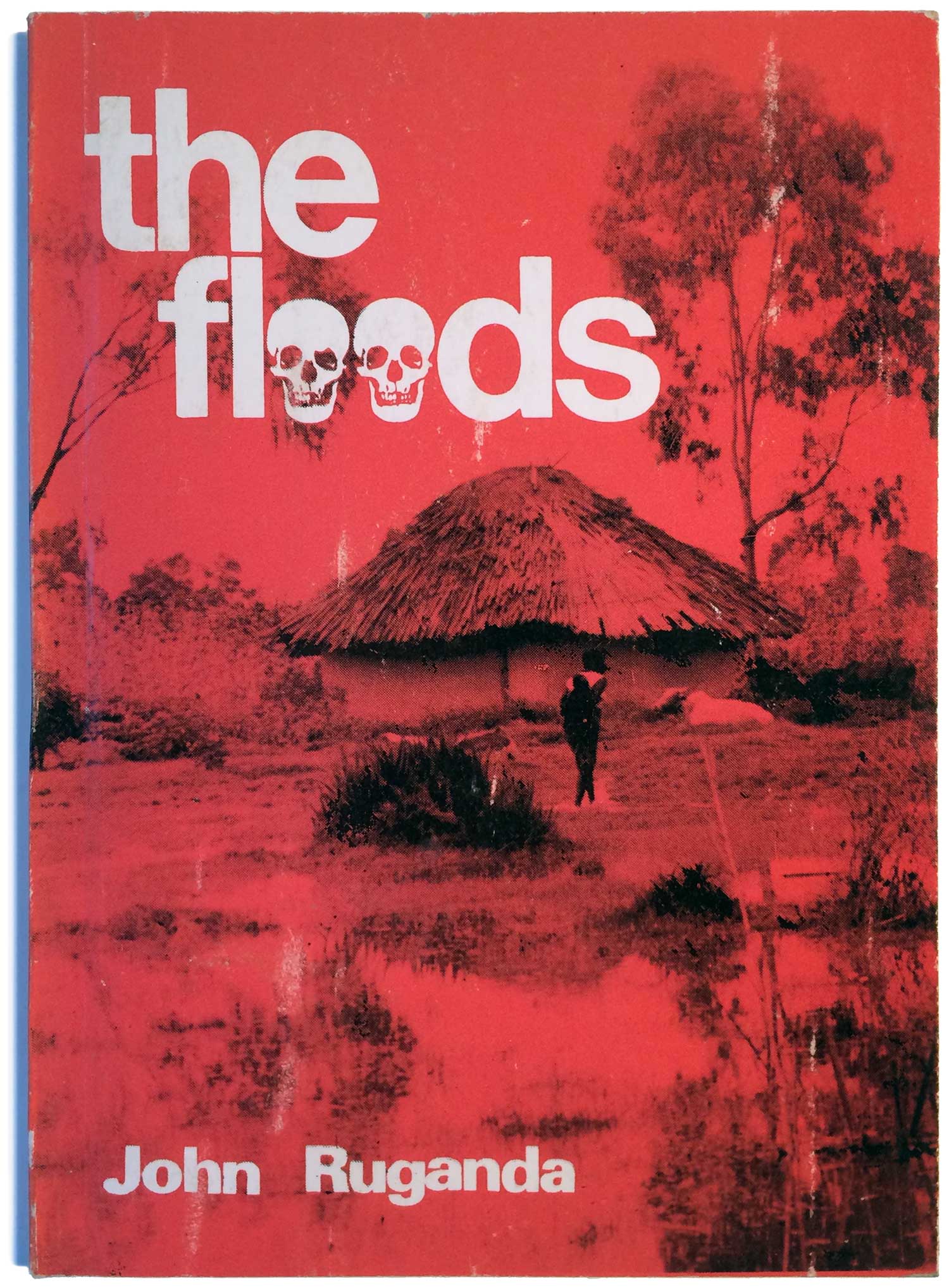

Below are two Hienemann Kenya books. Both were originally published by East African Publishing House, these are 1988 reprints. They both have many of the elements most African small press books share: poorly printed covers with ink that easily wears off, awkward trimming, analog design elements (notice the uneven baseline for John Ruganda’s name). They are great looking books produced with extremely limited resources—they do not feel like precious book objects, but stories that demand to be shoved in pockets, traded around, and most importantly, read. The Ogot novel is still in print, but is now being printed on-demand and distributed by East African Educational Publishers.

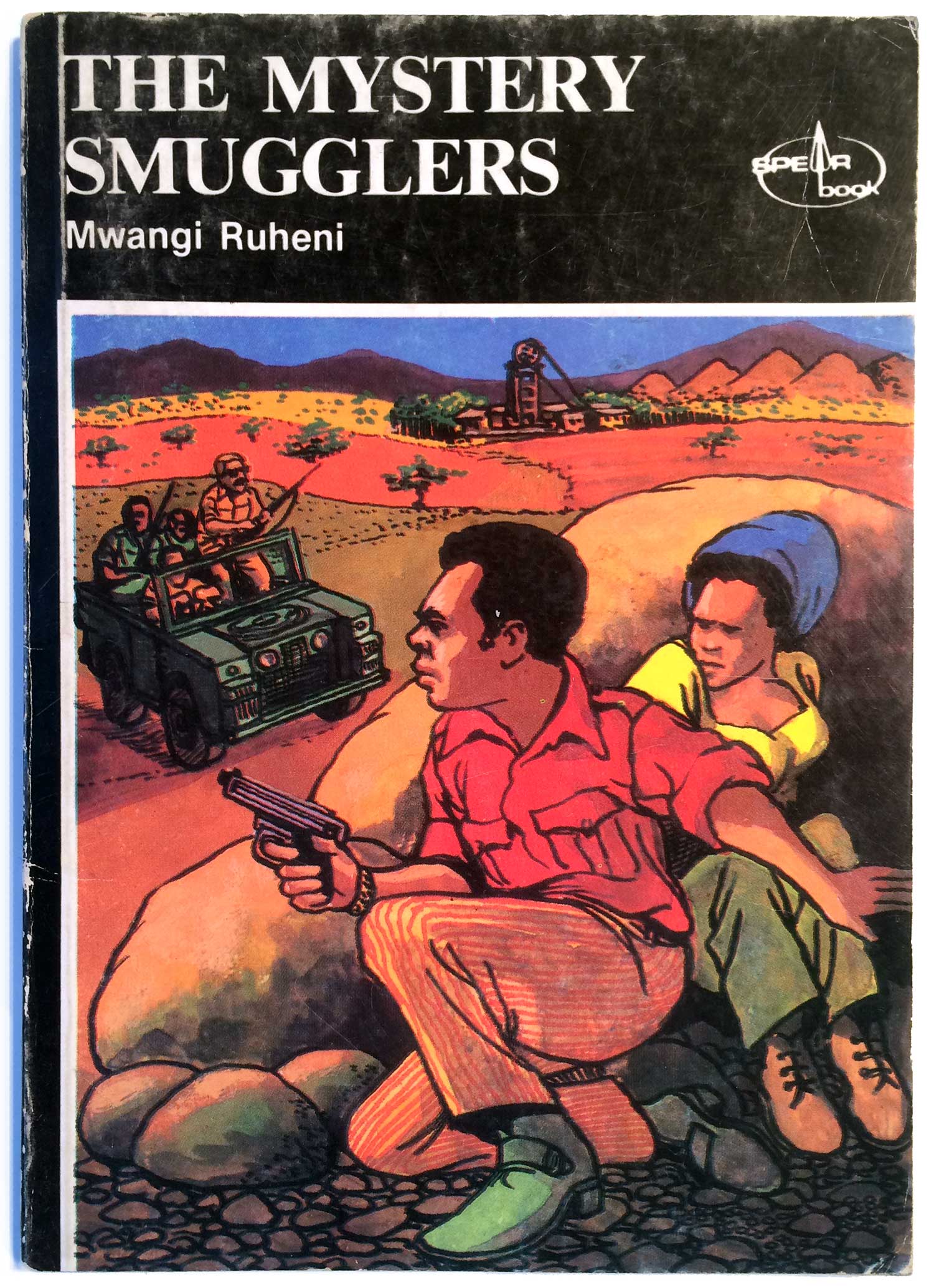

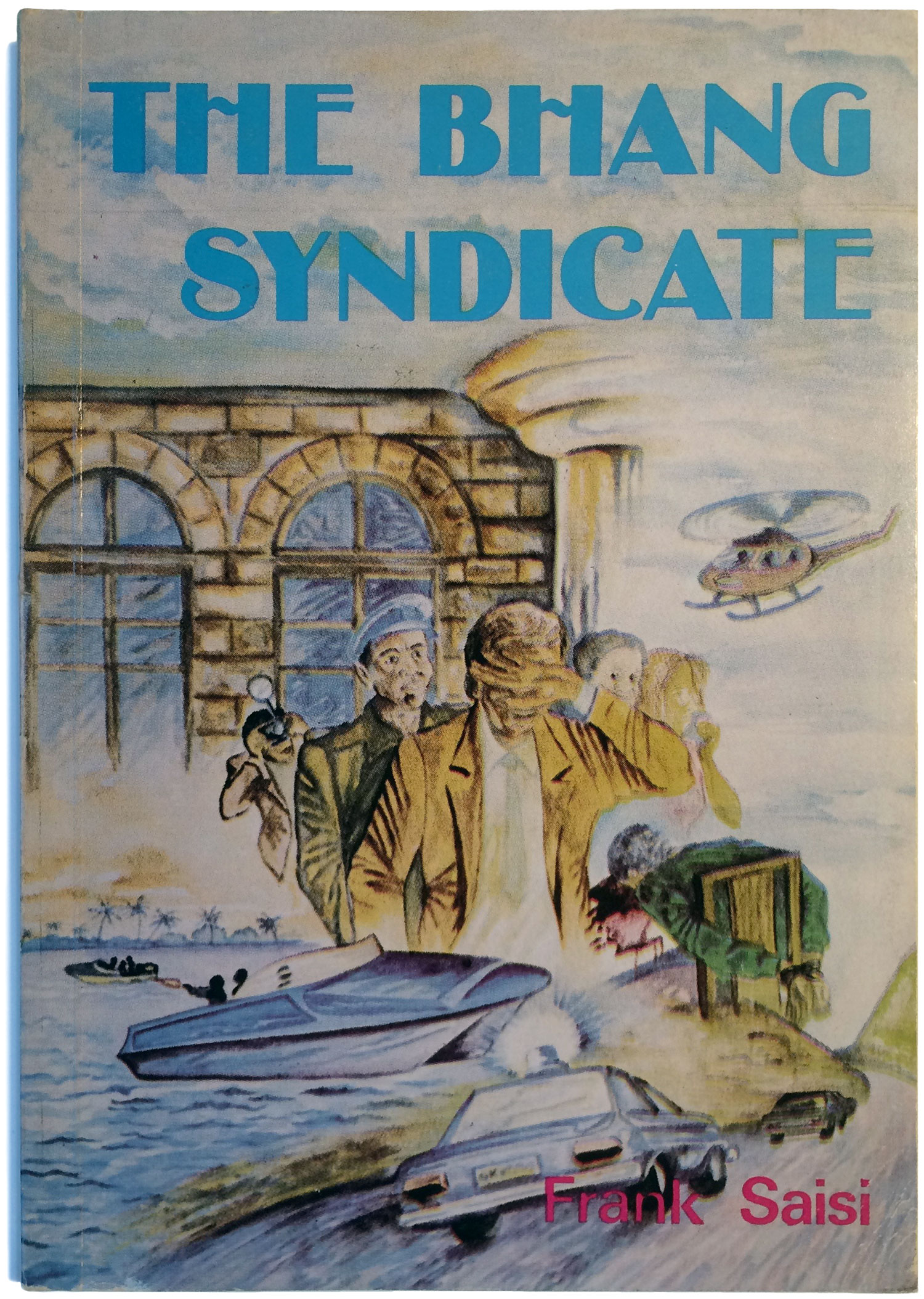

I can’t figure out the exact evolution, but I believe Spear Books started out as independent publishers of a wide range of titles, but at some point was absorbed by Hienemann Kenya, and became their outlet for young adult adventure novels and genre fiction. Below are one of each. Ruheni’s Mystery Smuggler is a high school level reader with a really nice and graphic cover illustration—featuring an 80s style African action hero. Frank Saisa’s The Bhang Syndicate is a sensationalist crime novel about Nairobi’s underworld. The Bhang Syndicate is interesting because it speaks to the large Indian population in Kenya, and their (supposed) role in organized crime.

To finish off, I’ve got one more title from Nairobi, and one from Ethiopia. Thu Tinda! by A Bole Odaga is a short story collection published in 1980 by Uzima Press. Uzima is a Christian press, mostly publishing religious books, but this is one of a handful of fiction titles. Uzima still exists and is apparently publishing, but I couldn’t find a website.

Belai Giday’s Ethiopian Civilization is a rare English-language title from Ethiopia. I suspect there is a fair amount of publishing that happens in Addis Ababa, but it is in Amharic, the dominant language of Ethiopia. And Amharic is pretty much only spoken and written in Ethiopia, so there isn’t much need or demand for distribution beyond the countries borders. This book looks like it was produced for tourists or the afro-centric set, not really for domestic use. We see the same African press characteristics on the cover as on so many books, with the duotone printing, mix of hand-drawn elements and basic desktop publishing, and ink that quickly rubs and wears down.

This is the forth in a series of posts about the African small press, especially in the 1960s through 80s. You can check out the other posts here, here, and here, and look for the next installment, about the East African Literature Bureau/Kenyan Literature Bureau.

This week’s bibliography: