Black Orpheus: A Journal of African and Afro-American Literature is likely the most important literary journal to emerge out of Africa, and one of the most important in the world during its heyday in the 1960s. Founded in 1957 by German expatriate, editor, and translator Ulli Beier, Black Orpheus took its name from the Jean-Paul Sarte essay “Orphée Noir,” which had been published as an preface to a collection of Francophone African literature edited by Léopold Senghor. Teaching in Nigeria, Beier had become fascinated with Yoruba culture, and wanted to develop a mechanism for giving Nigerian authors a broad, international audience. The journal quickly became a central for the emerging literary scenes in both Anglophone and Francophone Africa, with contributions from an amazingly wide and star-studded cast of African writers, including Chinua Achebe, Camera Laye, Ezekiel Mphahlele, Gabriel Okara, Lenrie Peters, and Wole Soyinka. In addition, other authors from the African diaspora were included, such as Léon Damas and George Lamming.

While politics, culture, and representation today are all fields with a certain obsession over authenticity, it’s really interesting that here we have a journal founded by a European that almost immediately was not only embraced by the actively decolonizing Black African cultural elite, but purposed as one of the main organs for articulating new ideas of “African-ness.” By 1960, Beier was sharing editorial duties with Soyinka (Nigerian) and Mphahlele (South African). In addition, the editorial board featured Aimé Césaire and Léopold Senghor. These are all heavy hitters, and you can really see Black Orpheus not only as a place for the emerging African literary scene to publish, but also to work out the critical apparatus for negotiating their relationship to the West, as well as to their own history and traditional languages and art forms.

From what I can tell, the journal was initially published in a run of 22 issues, from 1957 through 1967. In 1968 a second volume was published, with a run of three issues, and then in the 1970s a third volume, with a run of four issues. I believe there might have been later attempts to revive the publication, but these first three volumes are considered the body of Black Orpheus.

I must admit to being heavily out of my depth. While much of what I post on this blog is from the radical fringe, with little research or literature available about it, this isn’t so for Black Orpheus. There are many academic articles about it, as well as at least three compilations of content published by mainstream presses. All this is to say that no one should take my amateurish writings here as anything but what they are, and I hope this post points people in the direction of both learning more about Black Orpheus, as well as checking out the actual journals themselves, which are extremely beautiful.

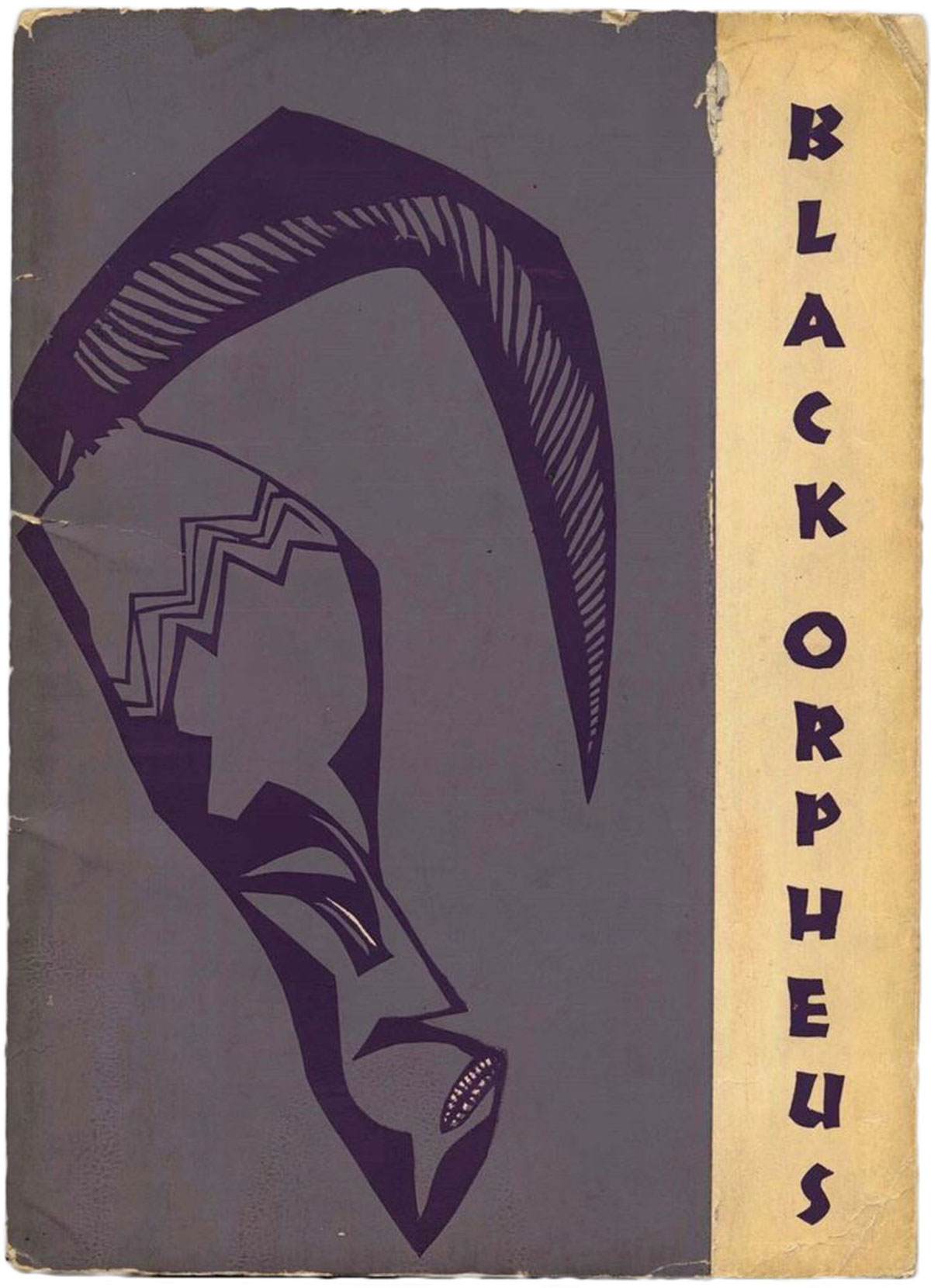

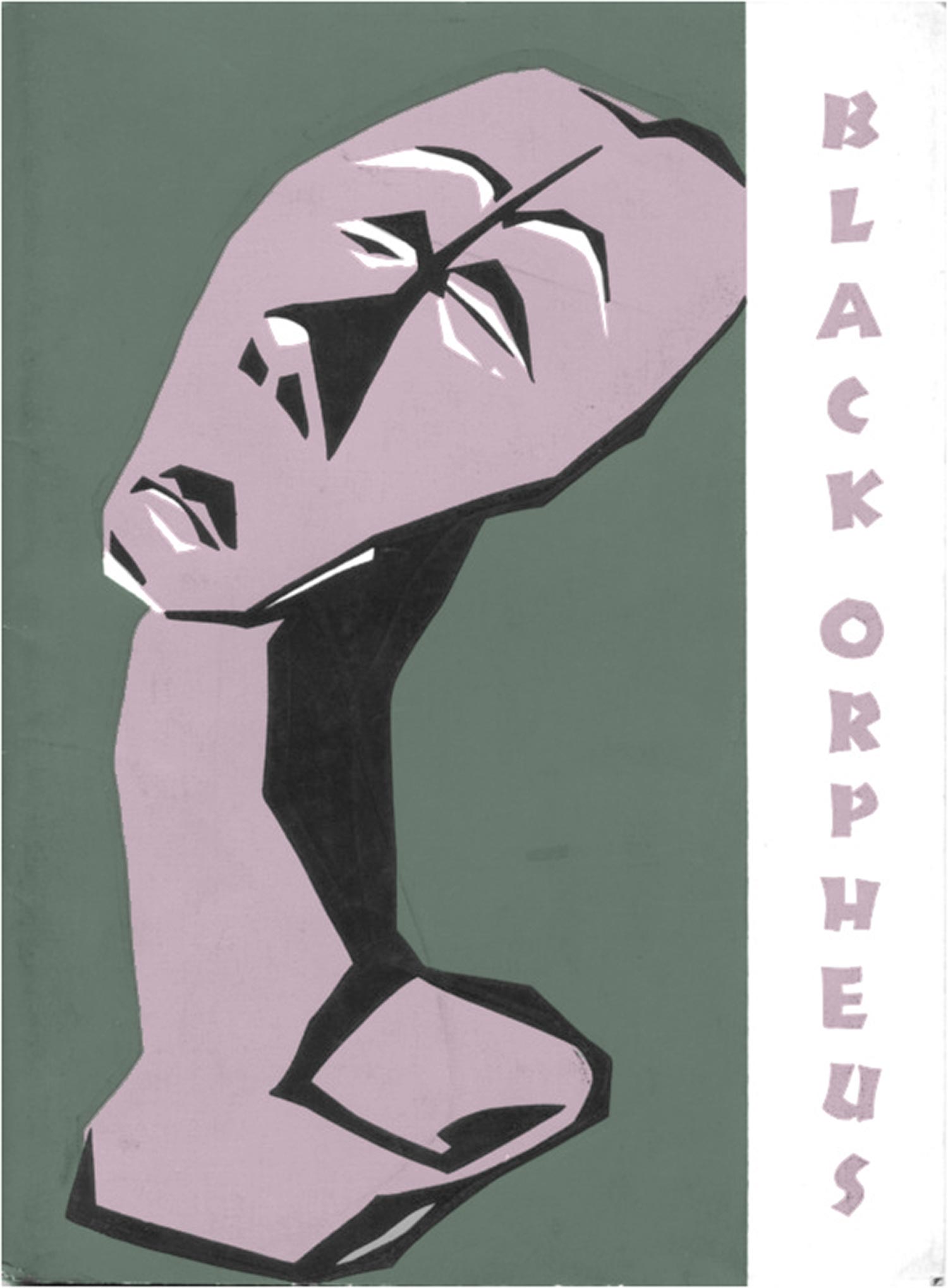

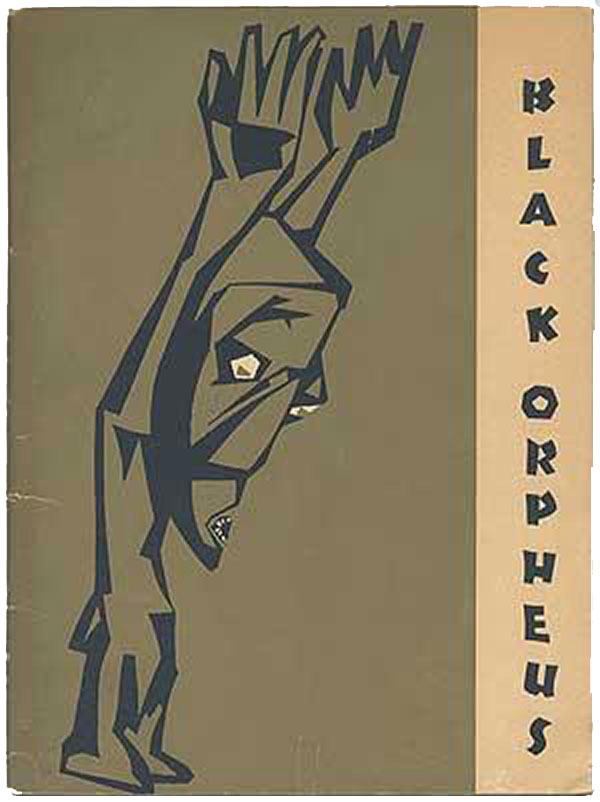

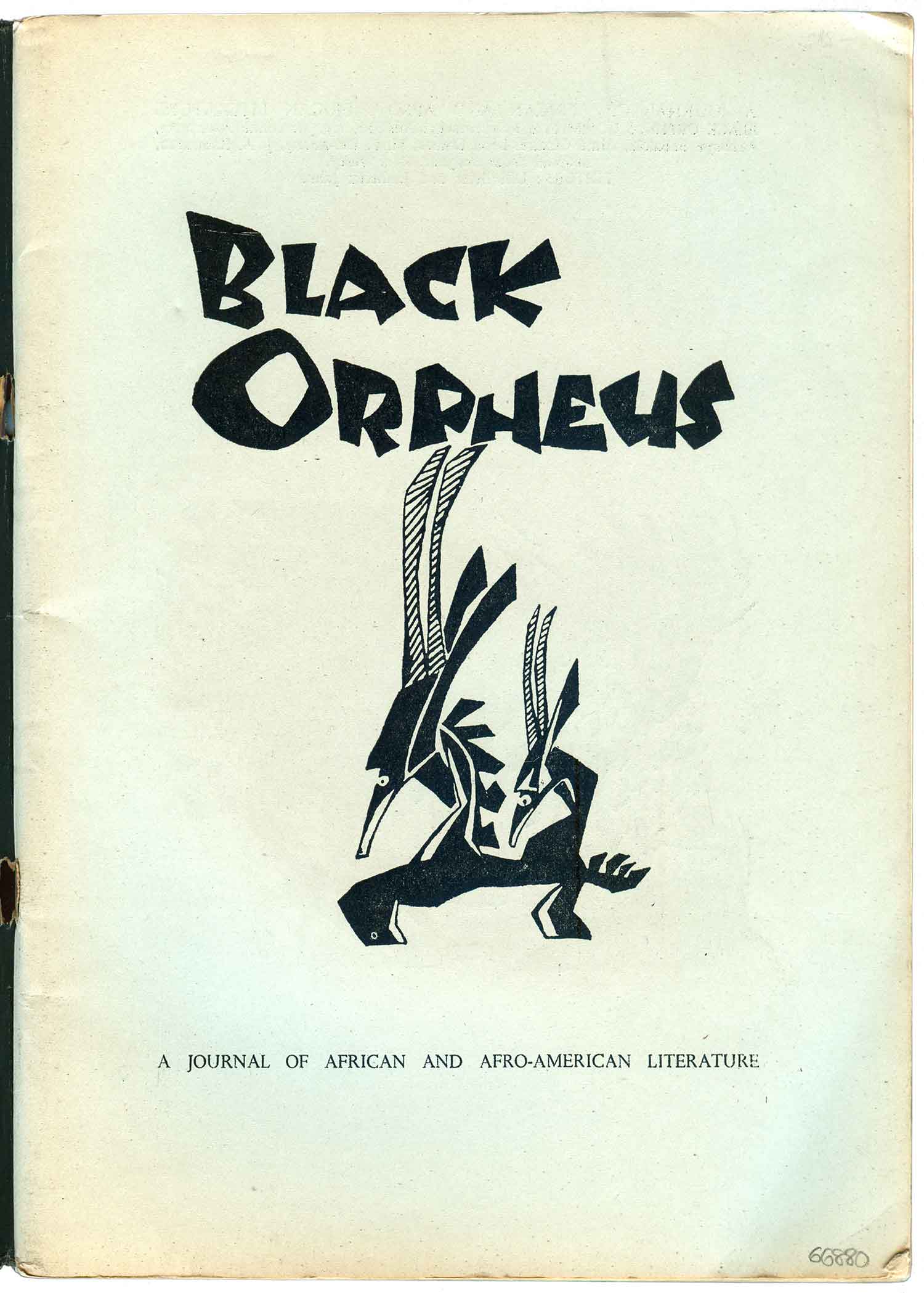

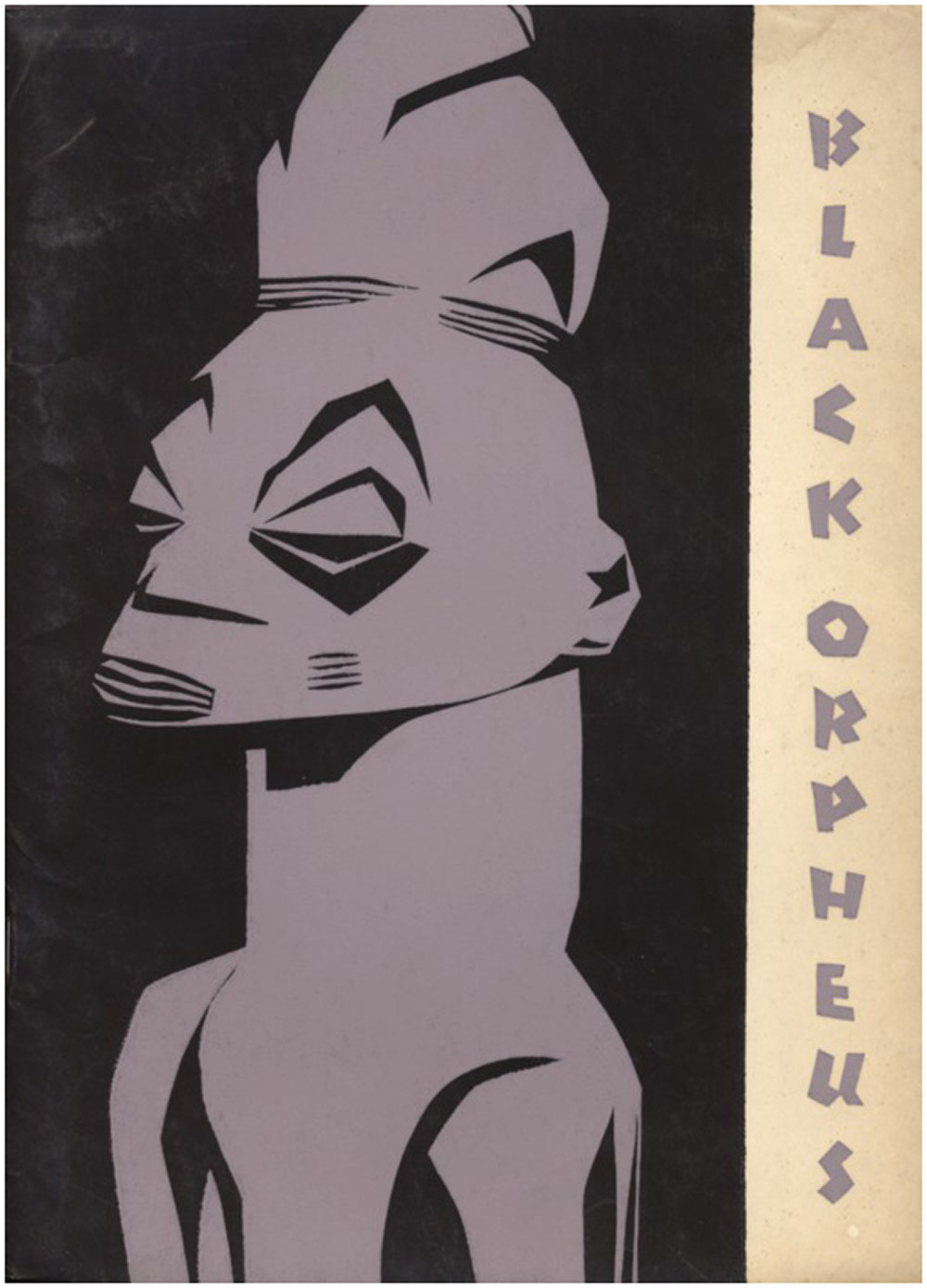

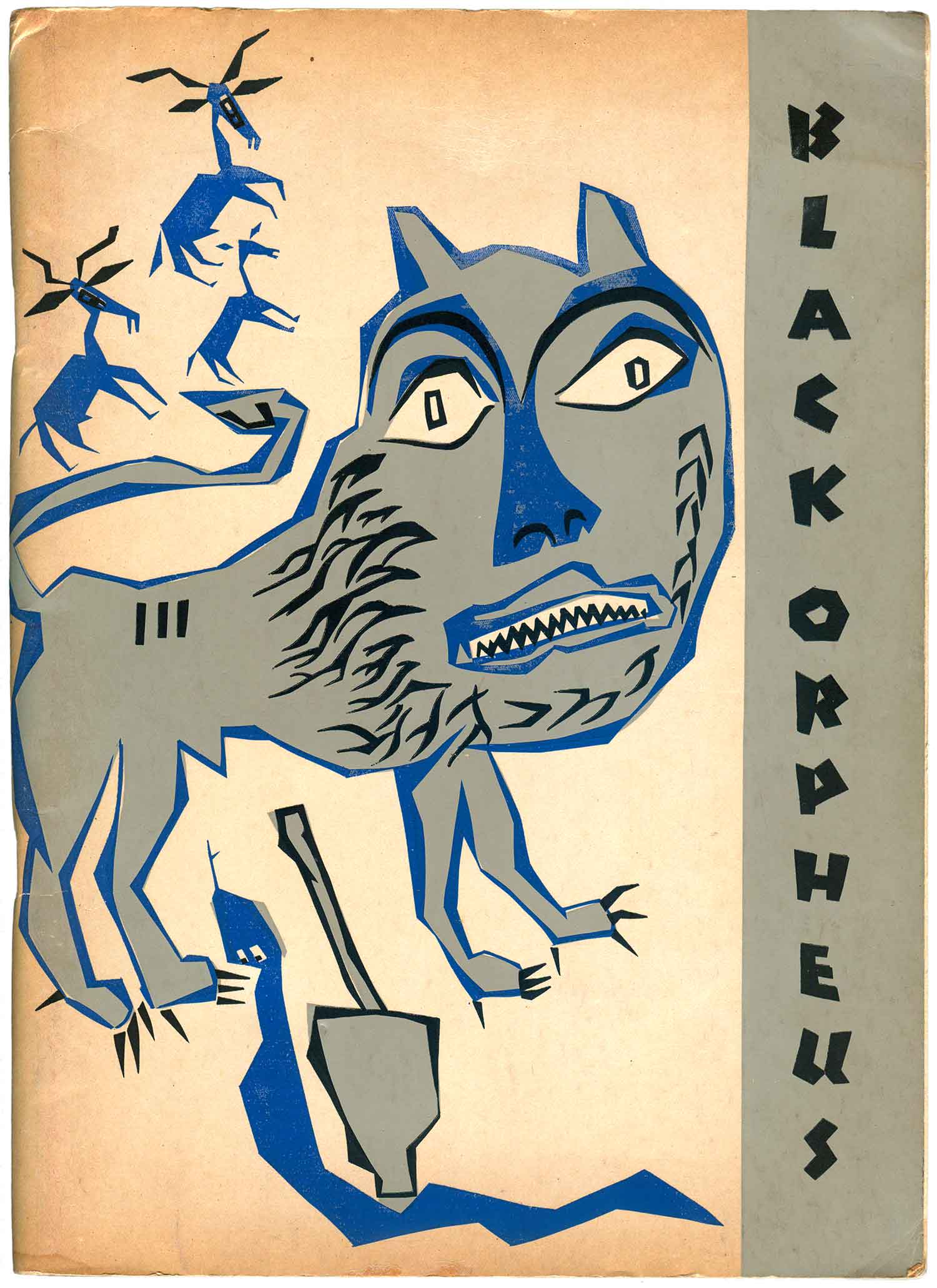

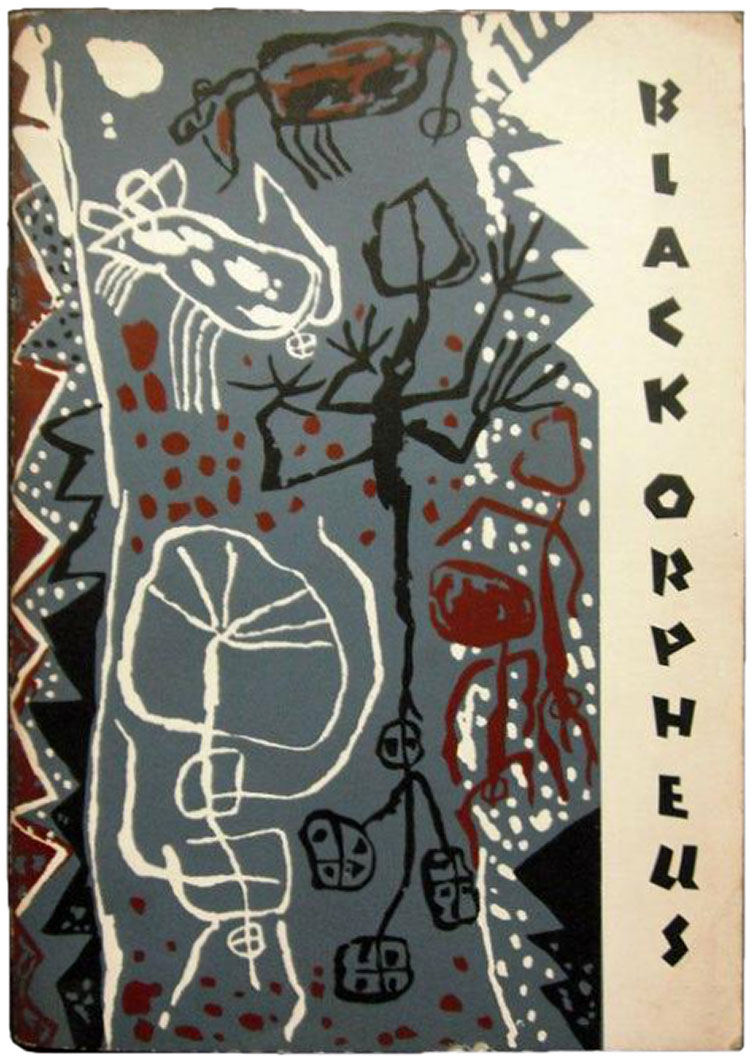

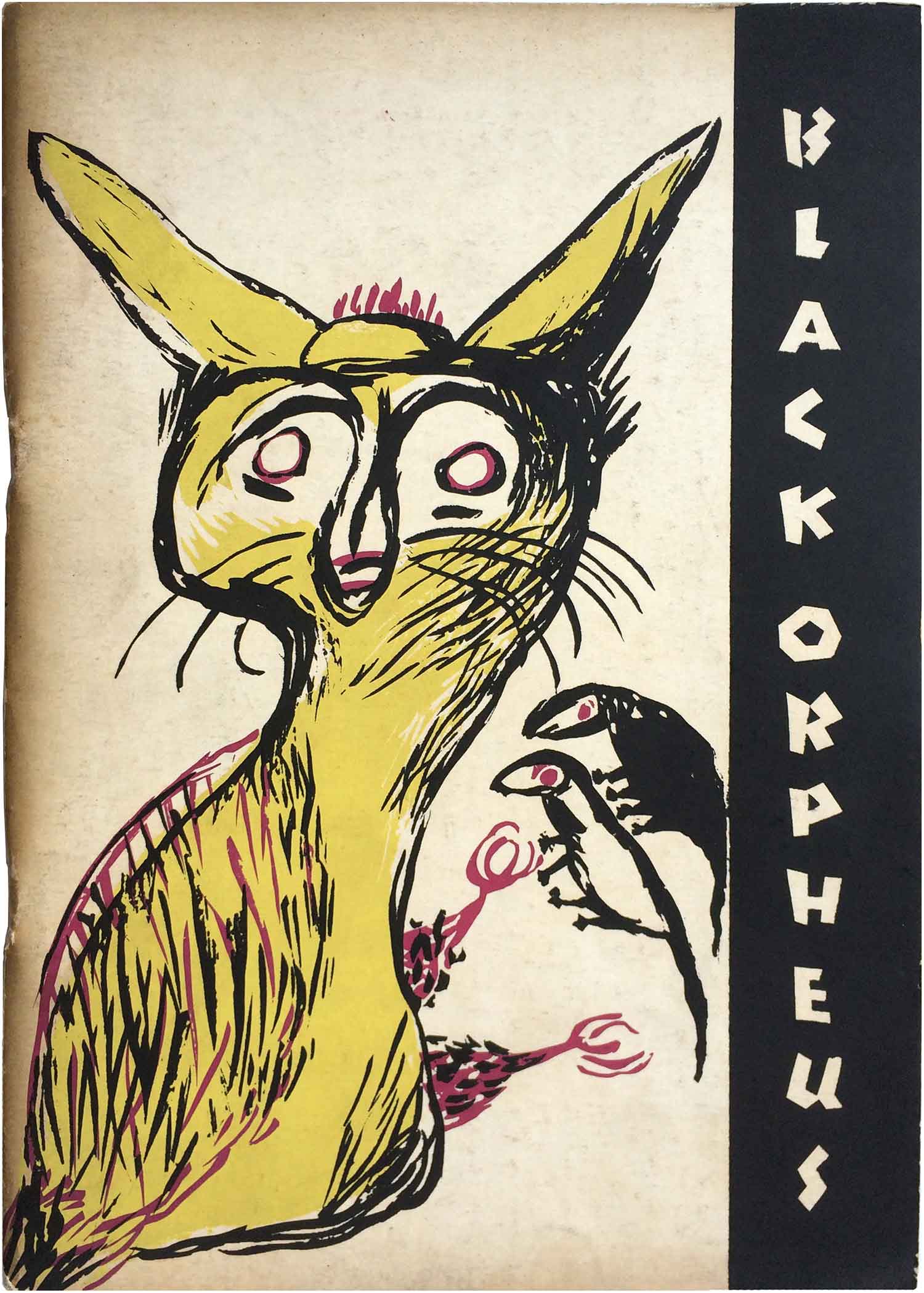

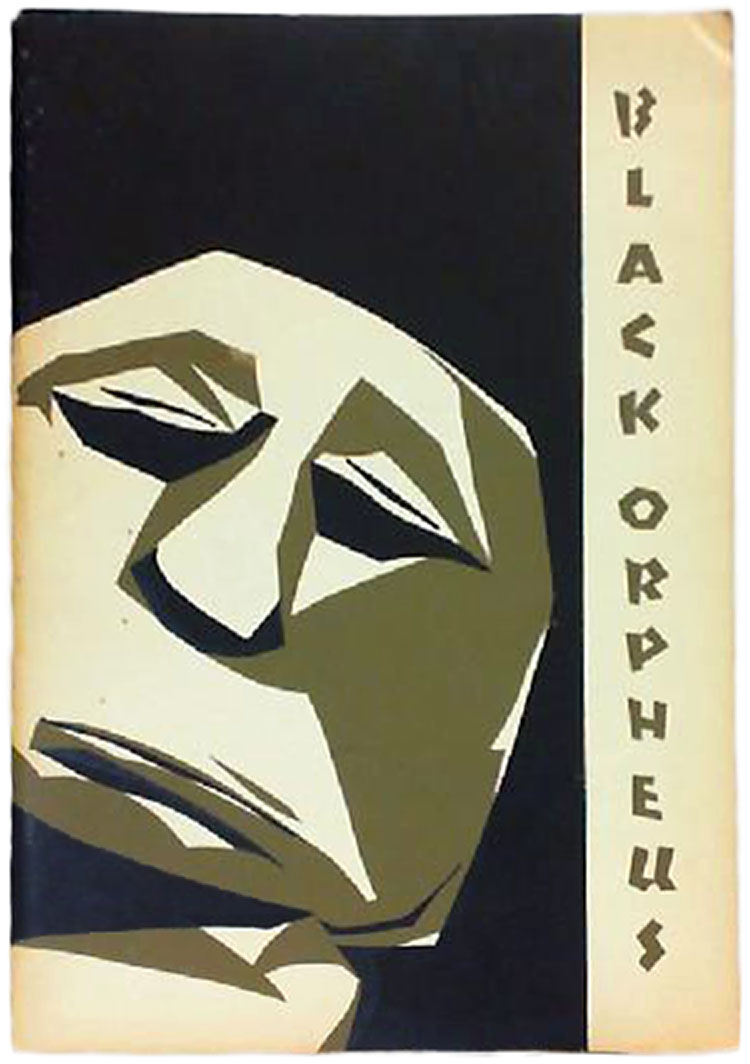

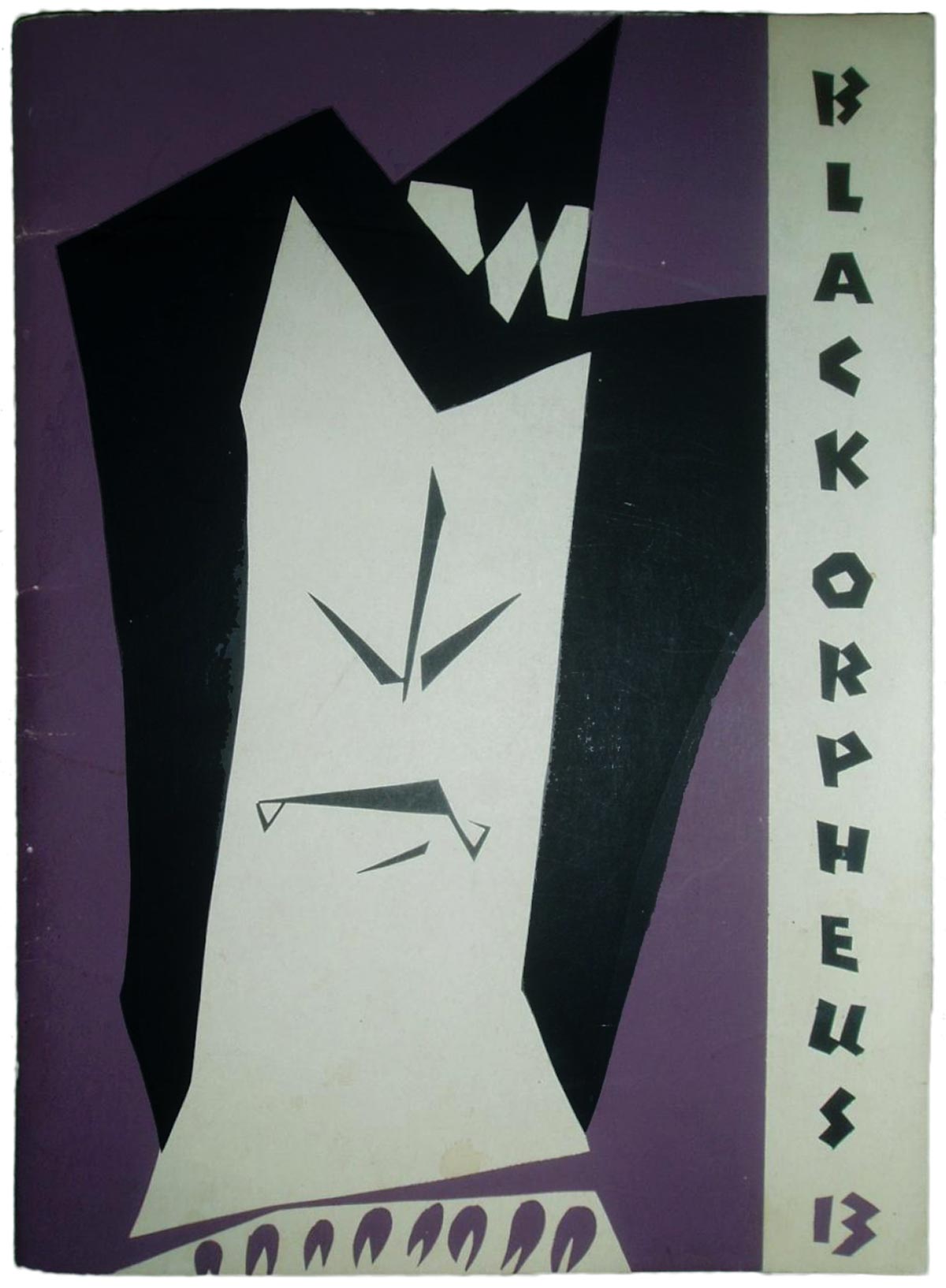

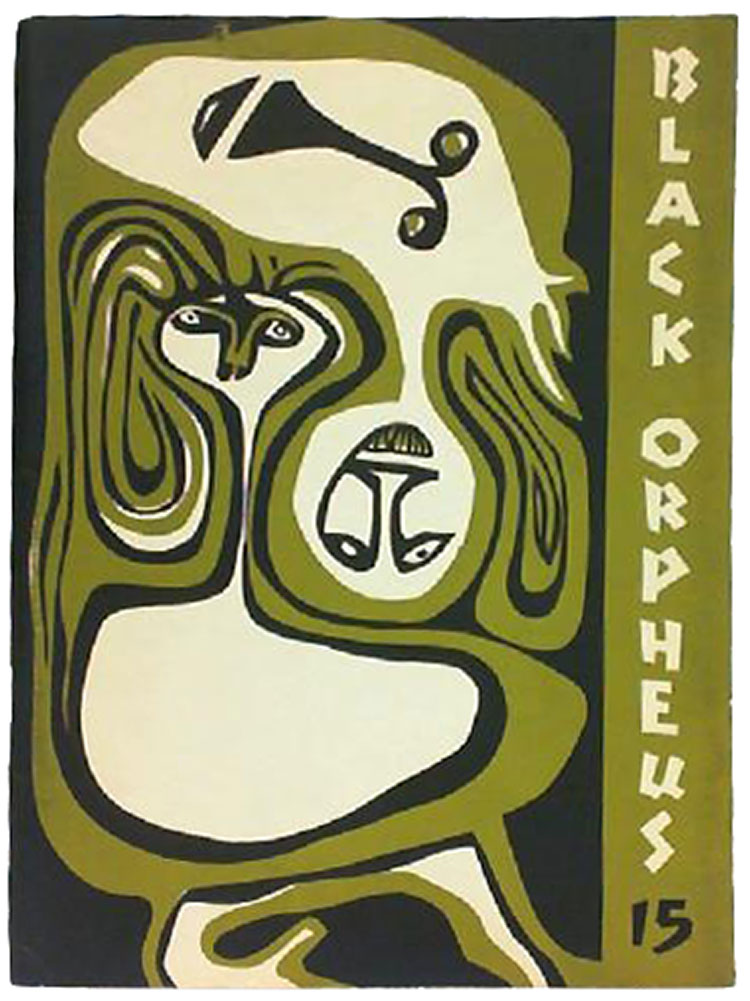

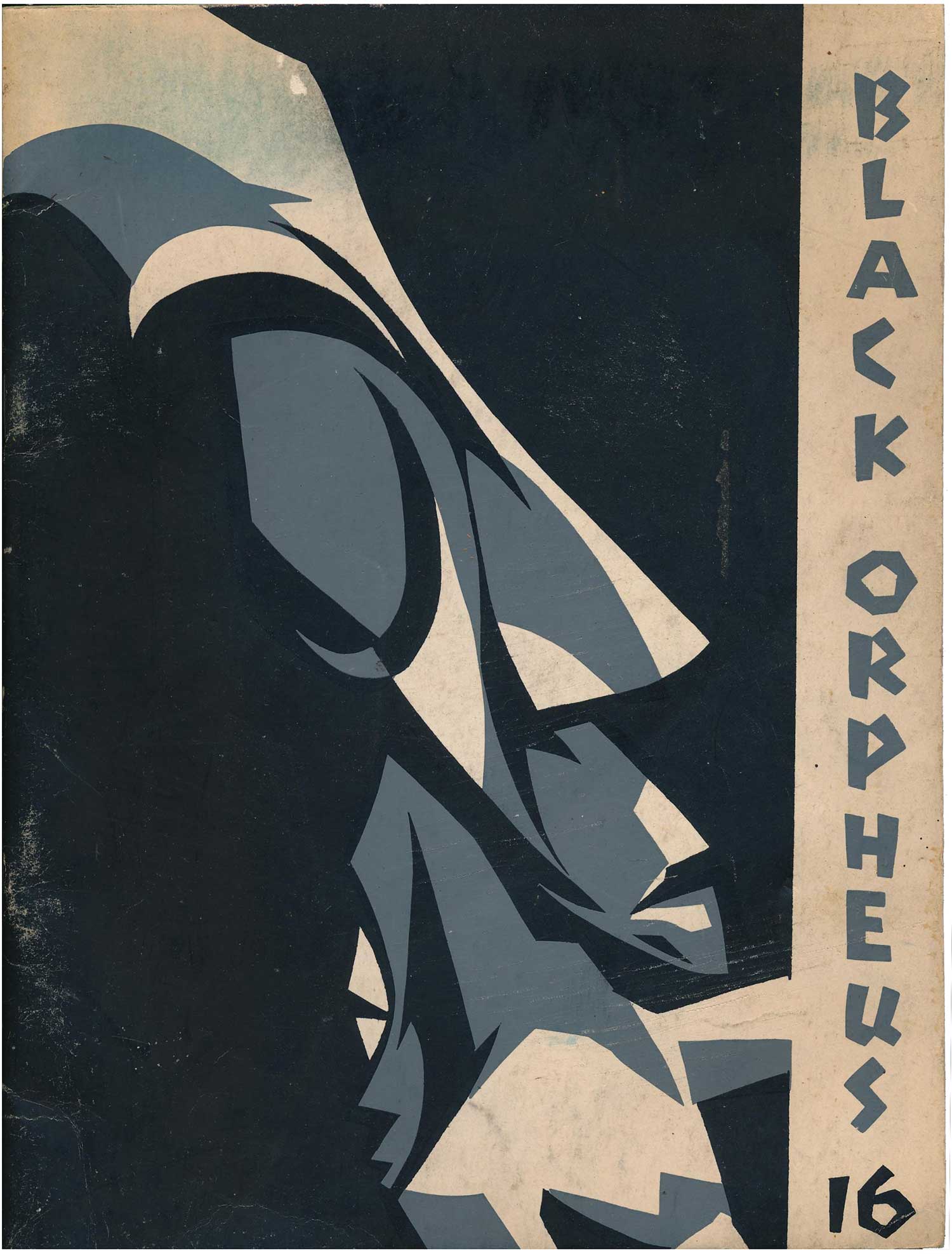

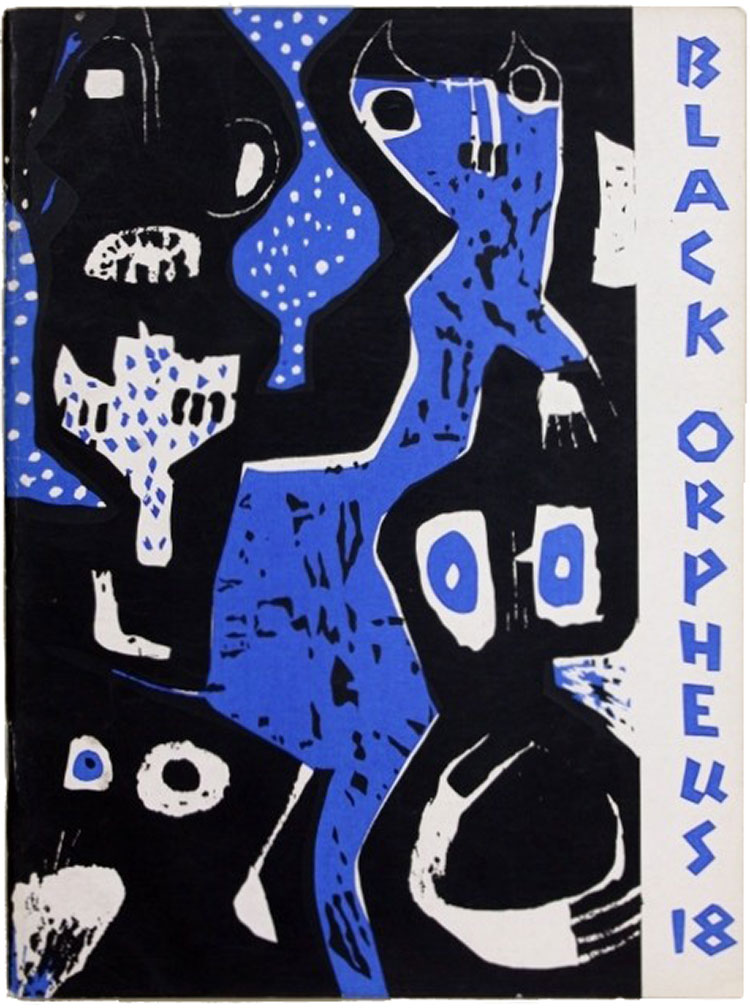

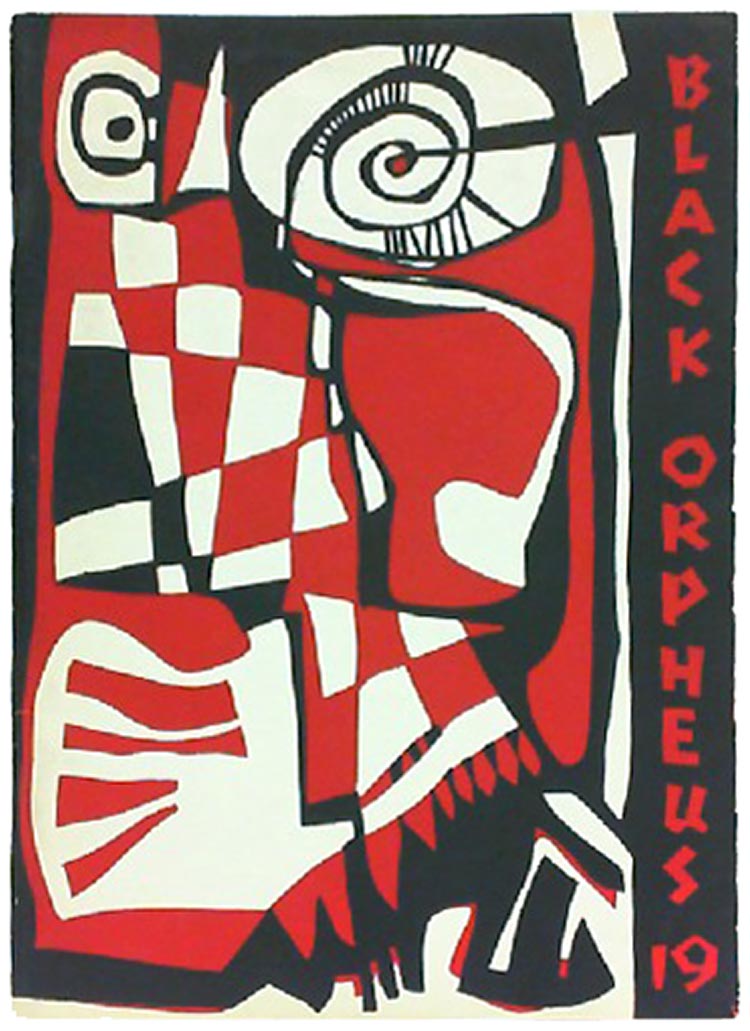

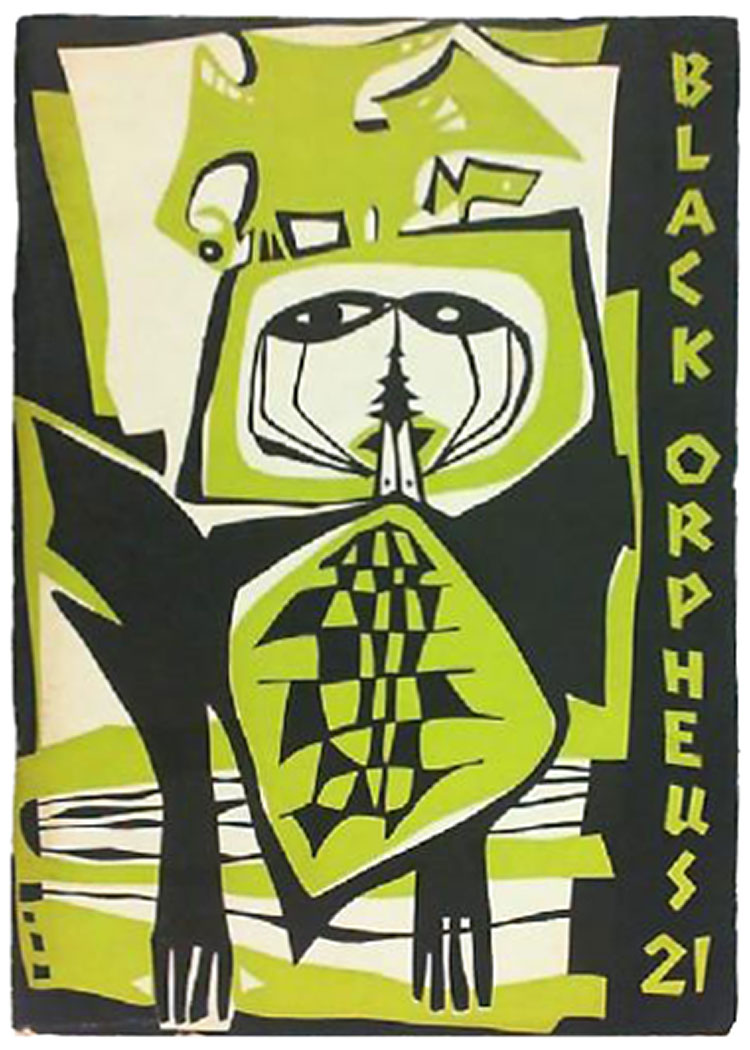

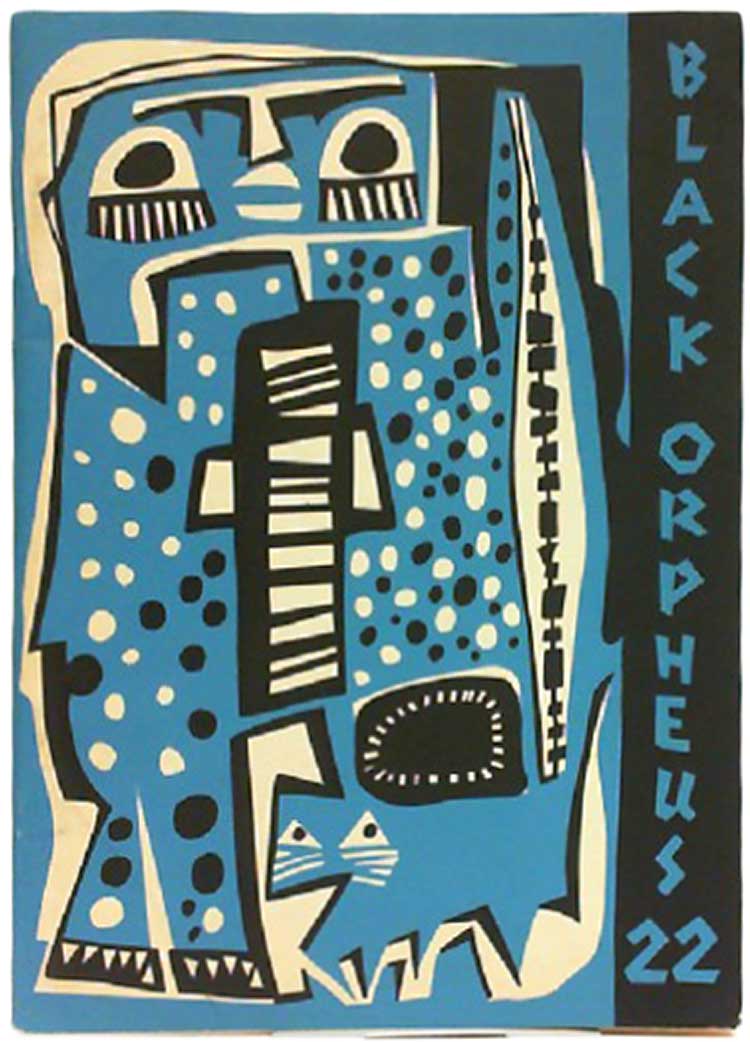

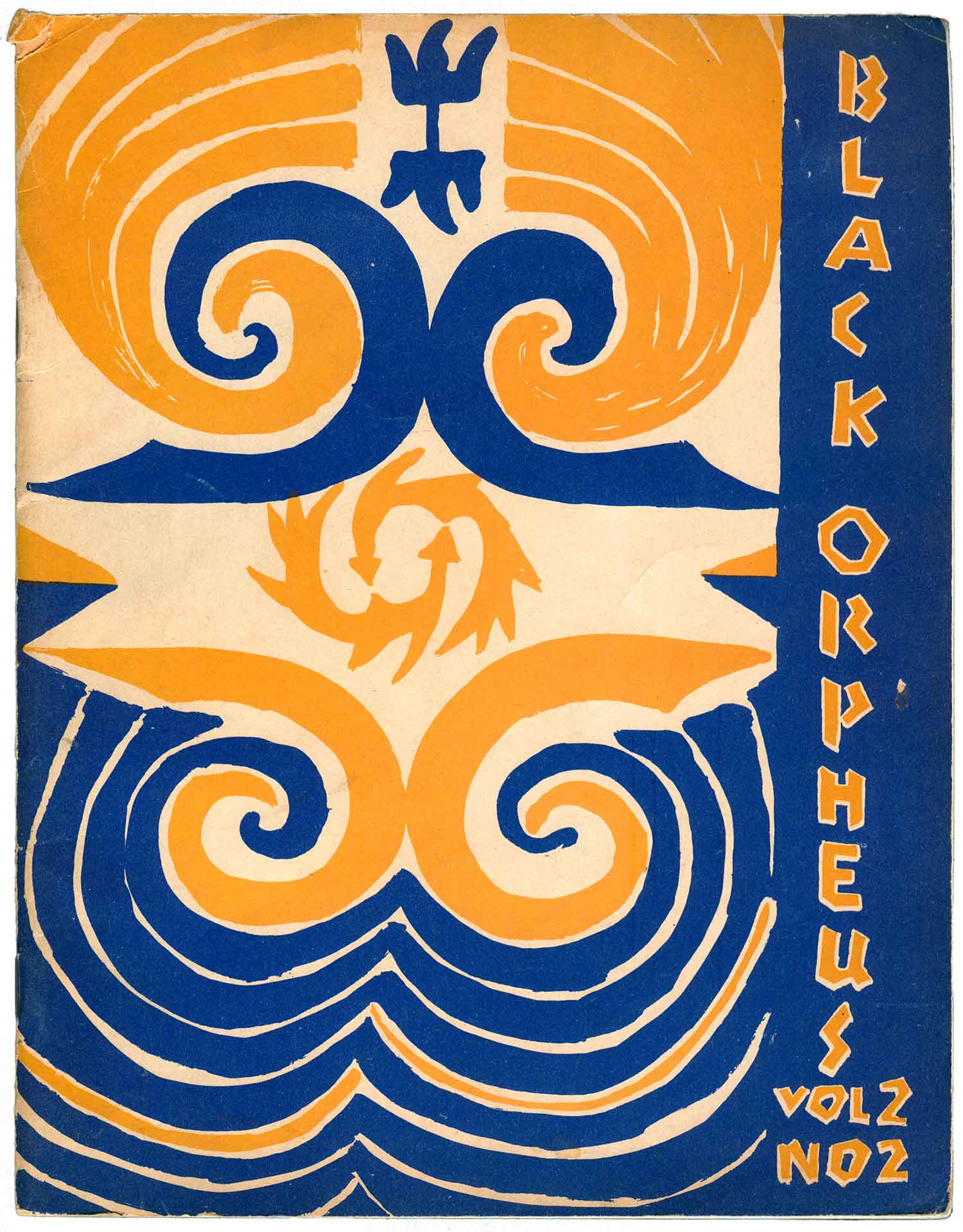

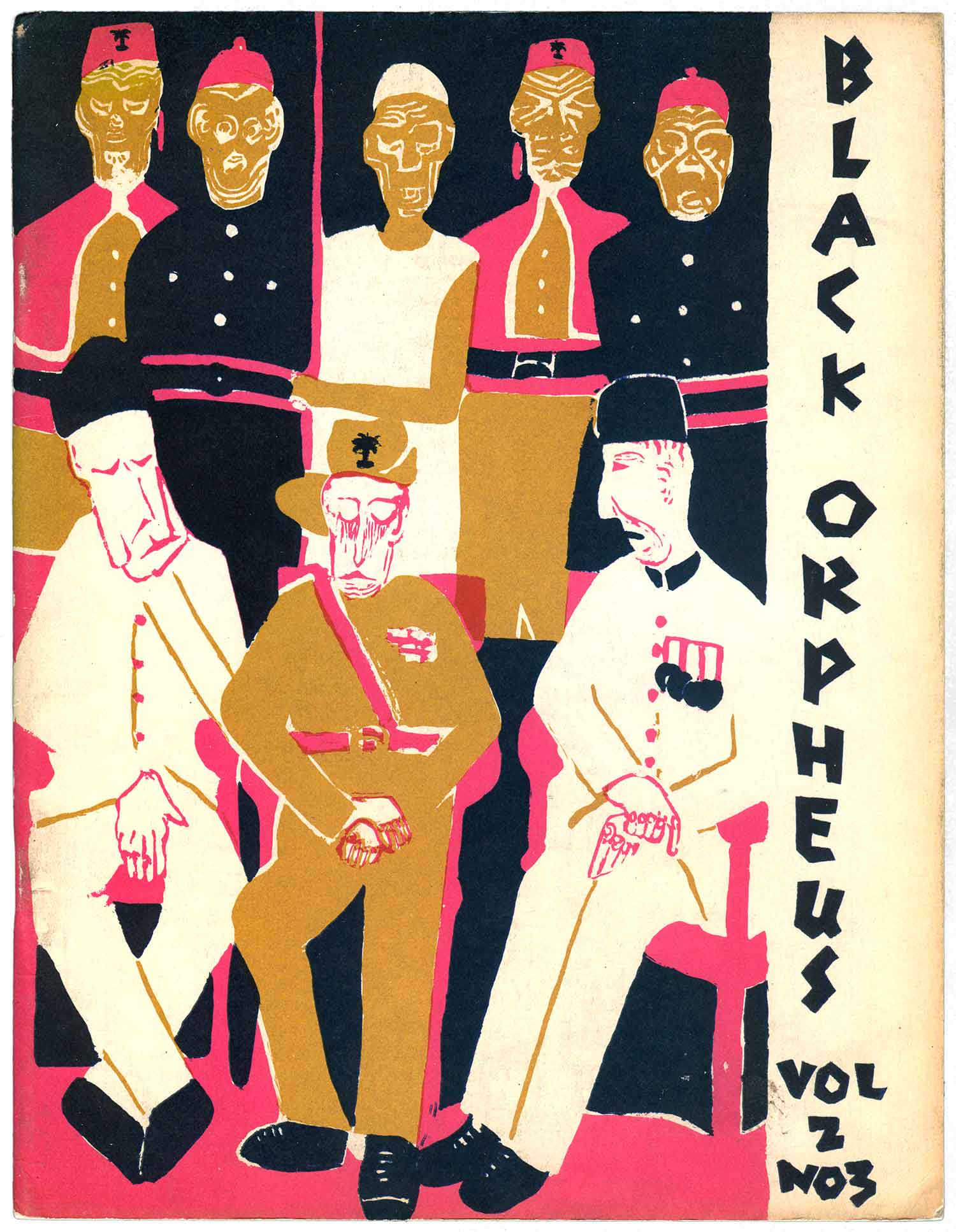

The cover designs for the first volume were all done by Susanne Wenger, an Austrian artist and Beier’s first wife. She had moved to Nigeria in 1950 with Beier. After catching tuberculosis, Wenger turned to traditional Yuroba religious practices as part of her healing regime. While Beier (and his second wife, Georgina Betts) left Nigeria in 1966 when the Biafran War broke out, Wenger not only stayed, but embedded herself further, becoming a Yoruba priestess and going on to found an artist cooperative in Osogbo.

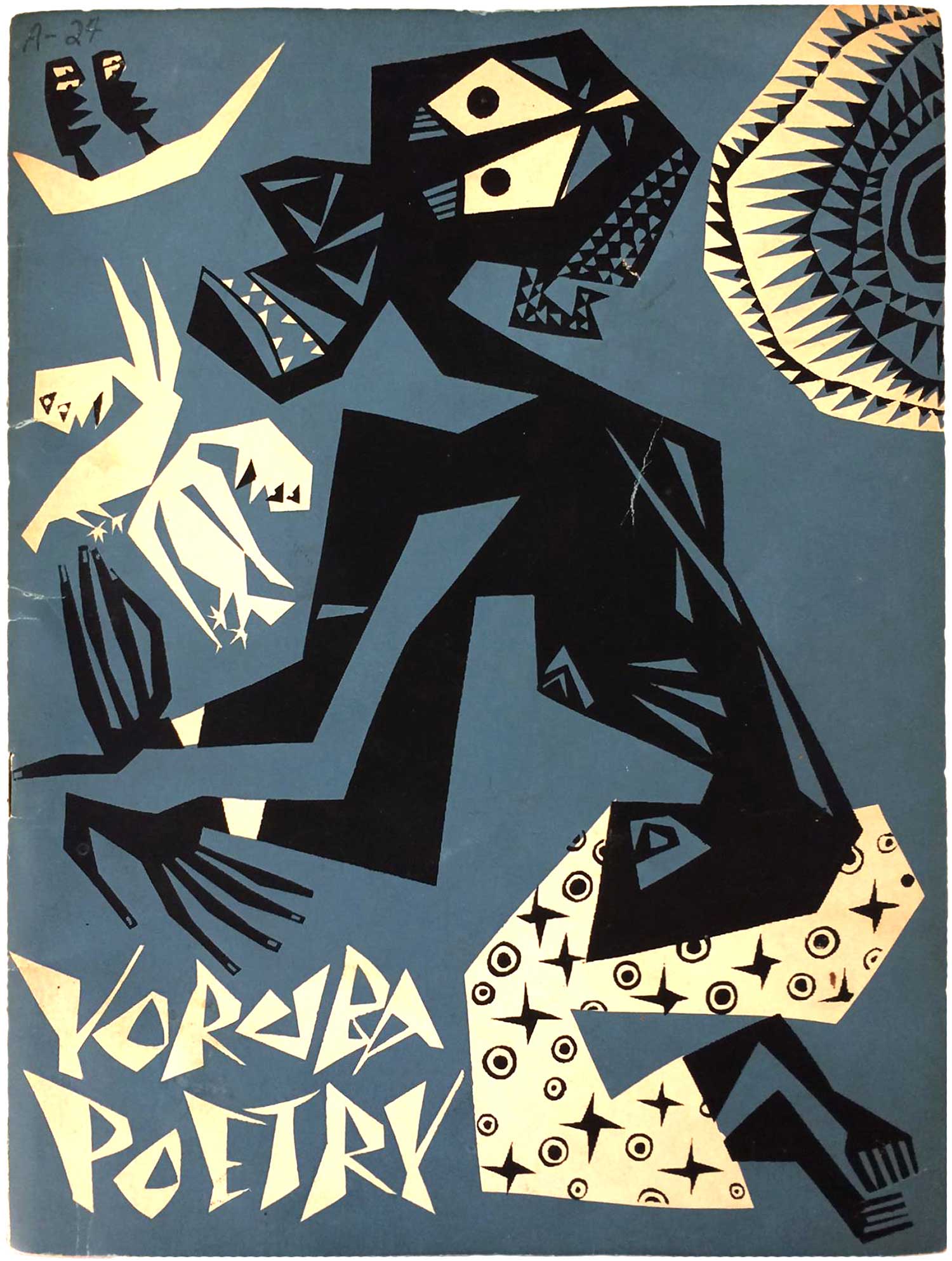

The covers are striking, every single one. What Wenger has done is to take pieces of traditional African art from across the continent and flatten and style them into punchy, compelling graphics. The first eight issues feature her interpretations of sculpture, and from there she begins to experiment with fabric patterns and other craft forms. The designs are usually simplified to two—or at most three—colors, and screen printed, which give the covers a tactile feel. While there is no questioning the power and beauty of the covers, they do raise interesting questions about representation. How did Wenger and Beier justify wrapping the magazine in European re-interpretations of African art? Why not use the art itself, which they regularly featured inside the magazine? What did intellectuals and critics like Achebe, Soyinka, and Césaire think of this practice?

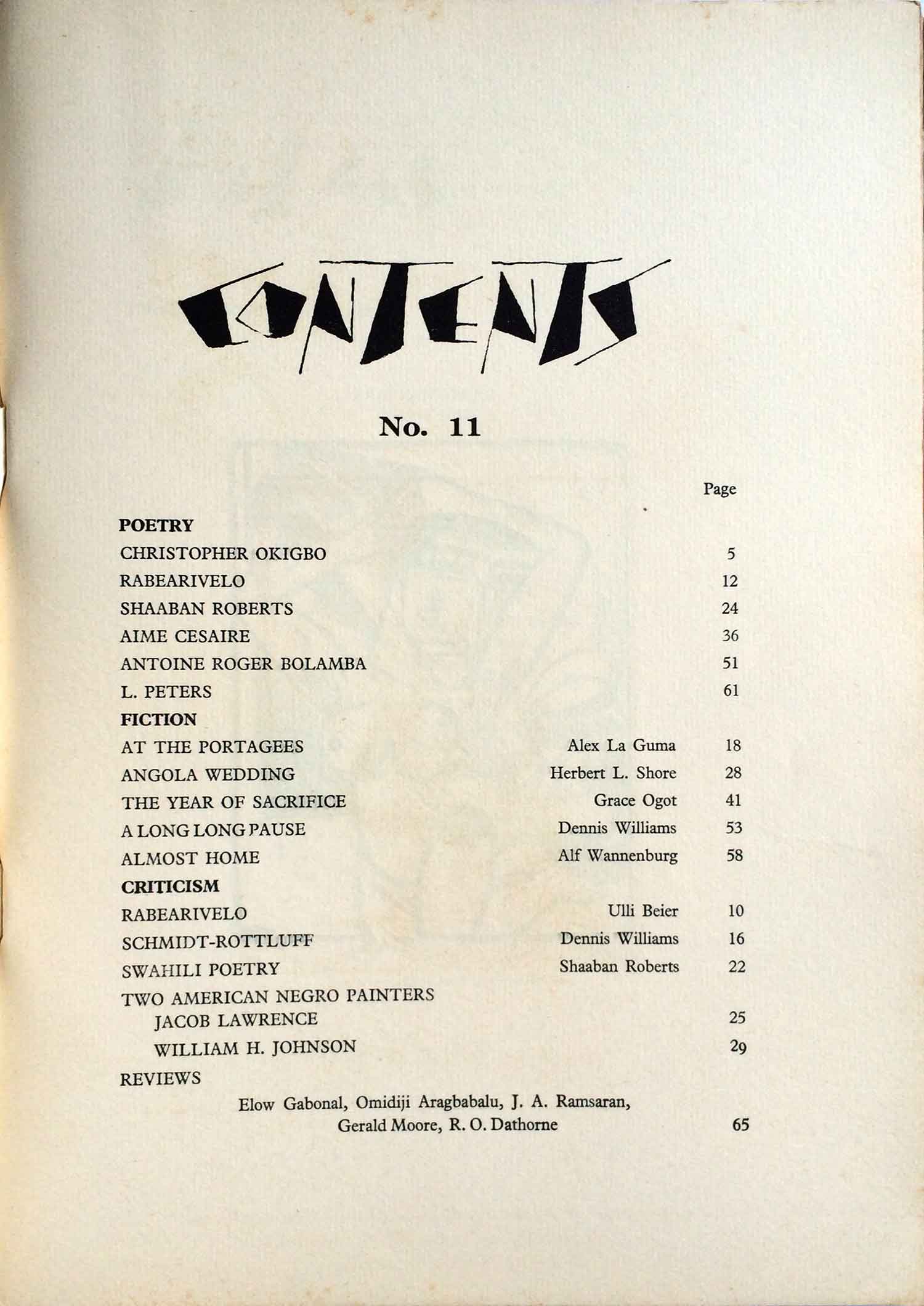

Speaking of the insides, they impress as well. Each issue is printed with set type, with the illustrations a combination of metal blocks or offset printed. In addition, all the titling is done in what I assume is Susanne Wegner’s hand drawn style, then cast and struck as blocks. All of the issues I have were printed by the Times Press in Lagos. The earlier issues are published by the Nigerian Ministry of Education, then in the early ’60s the publishing is taken over by the newly founded Mbari Club. (There will be much more information about the Mbari Club and it’s publishing arm in the next installment of Judging Books by Their Covers).

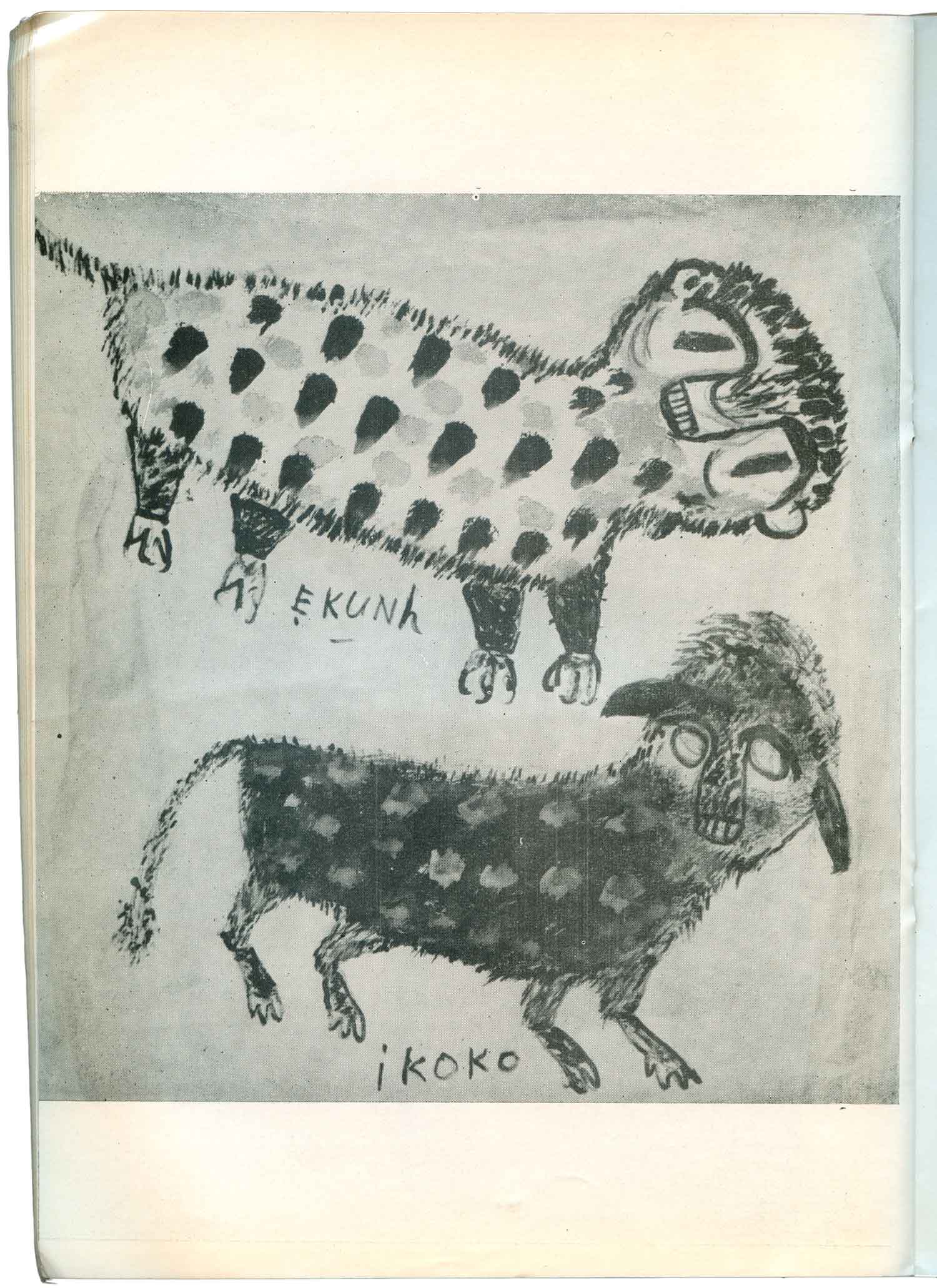

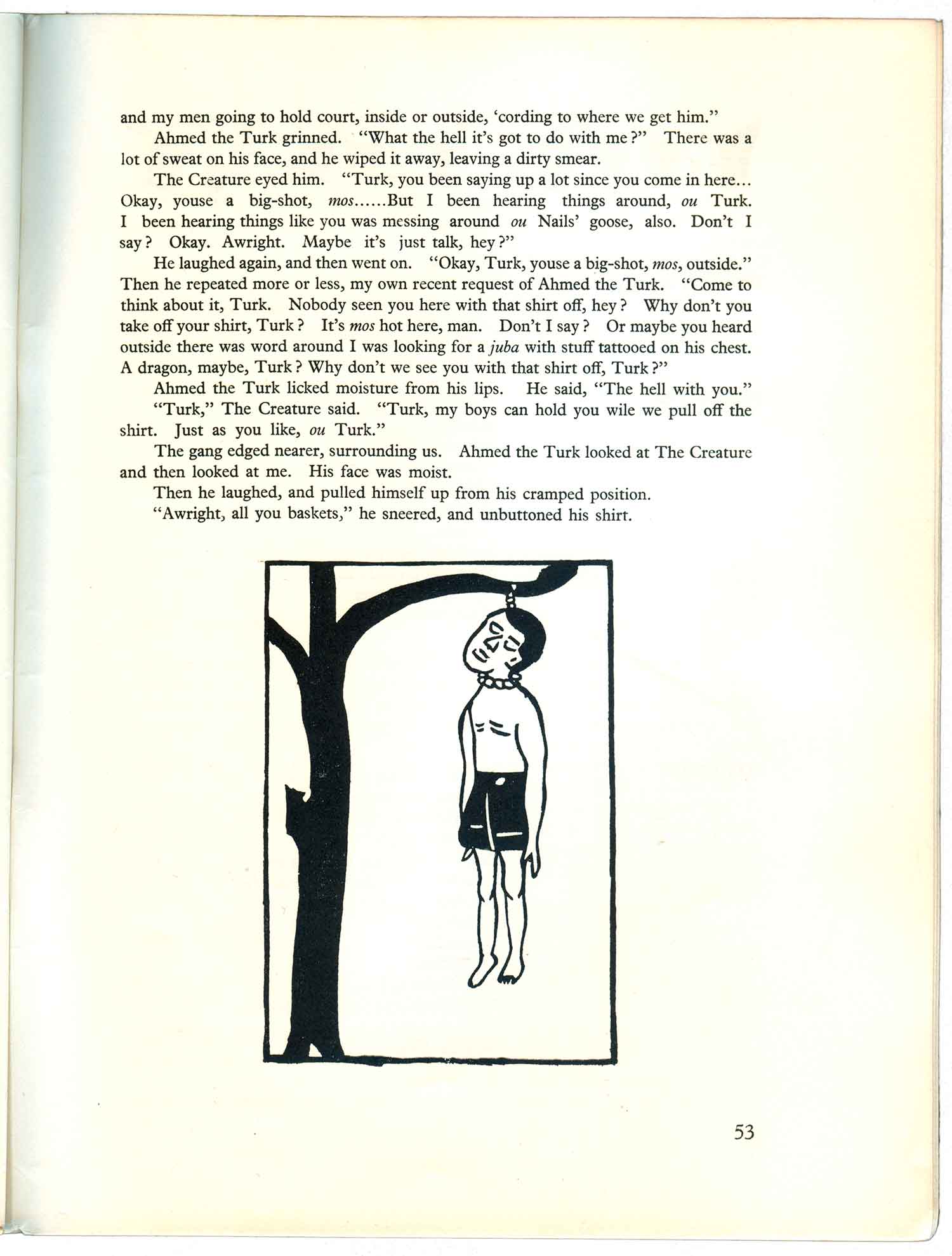

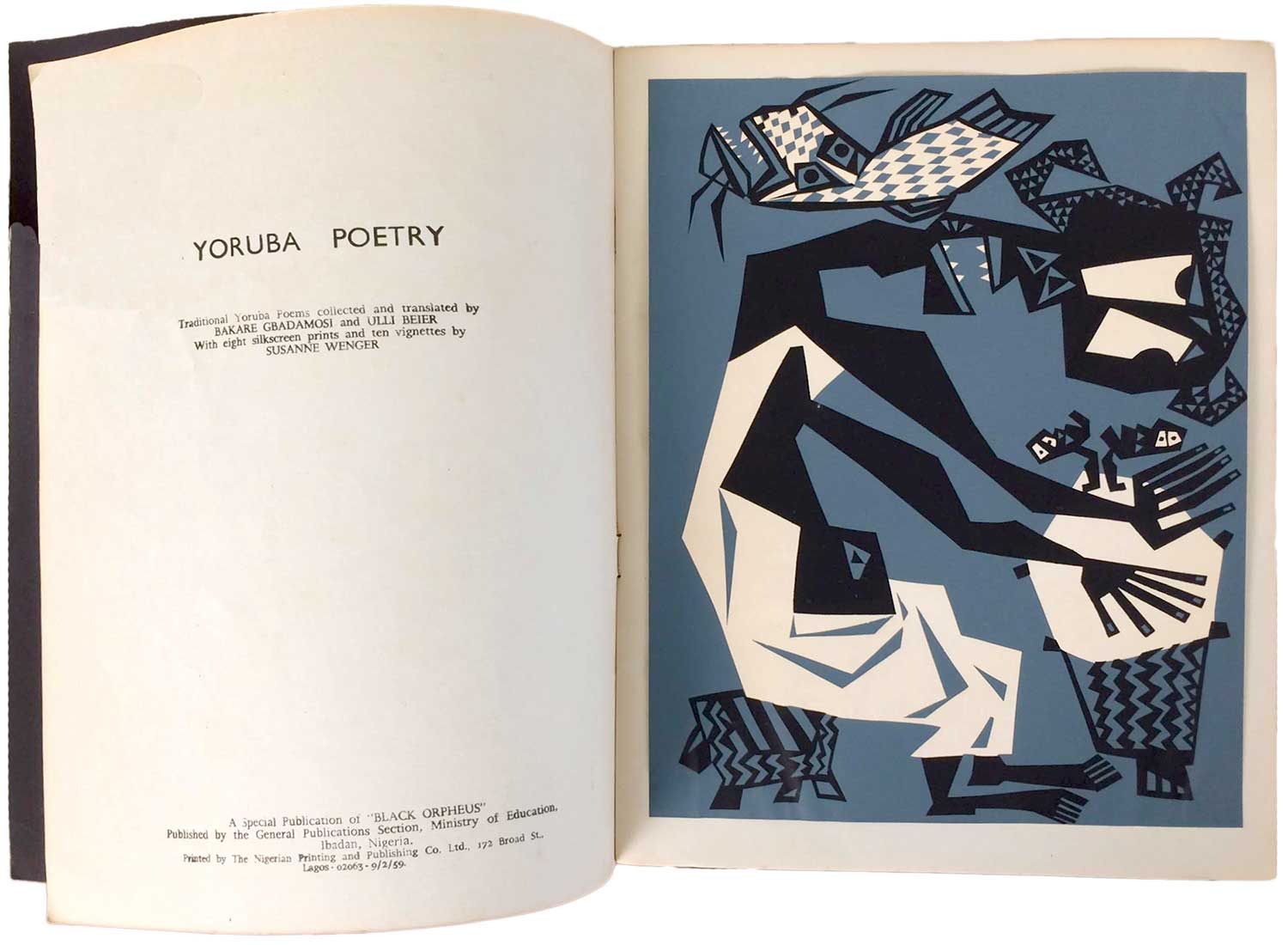

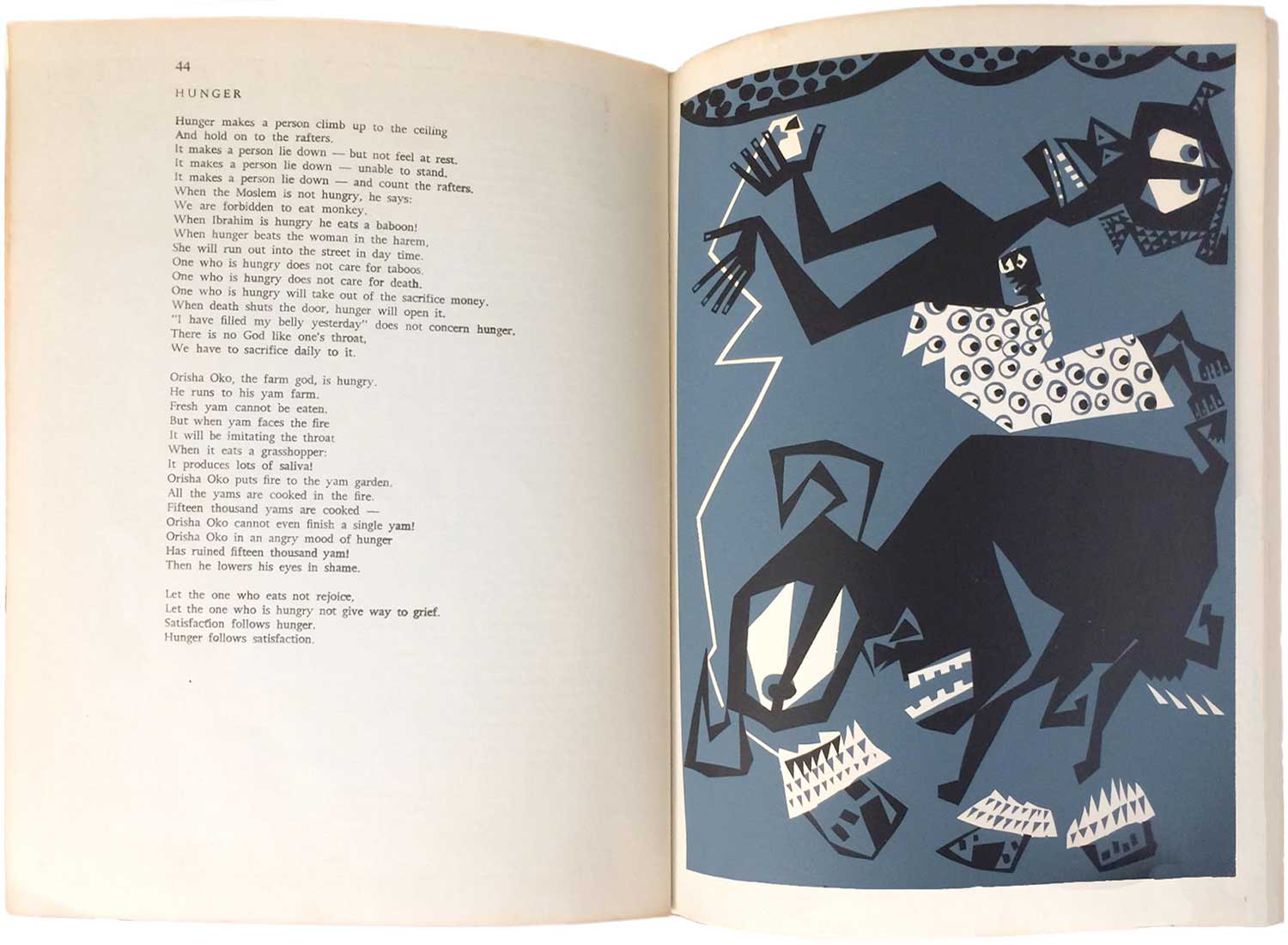

The images within in the magazine hold an interesting space somewhere between illustration, ornamentation, and free-standing art. Many issues contain portfolios of photographic reproductions of sculpture, architecture, and paintings. These are printed in halftones on thin, coated stock. By contemporary standards, they are not the highest quality, but it seems meaningful that clearly a significant effort was made to elevate and highlight visual arts within the publication. I love the spot illustrations. In issue 14 (below) there is a significant feature on Onitsha Market Literature, and all of the images in the issue are from Onitsha pamphlets. As you can see, what at first glance appear to be light little sketches are ultimately often dark and strange.

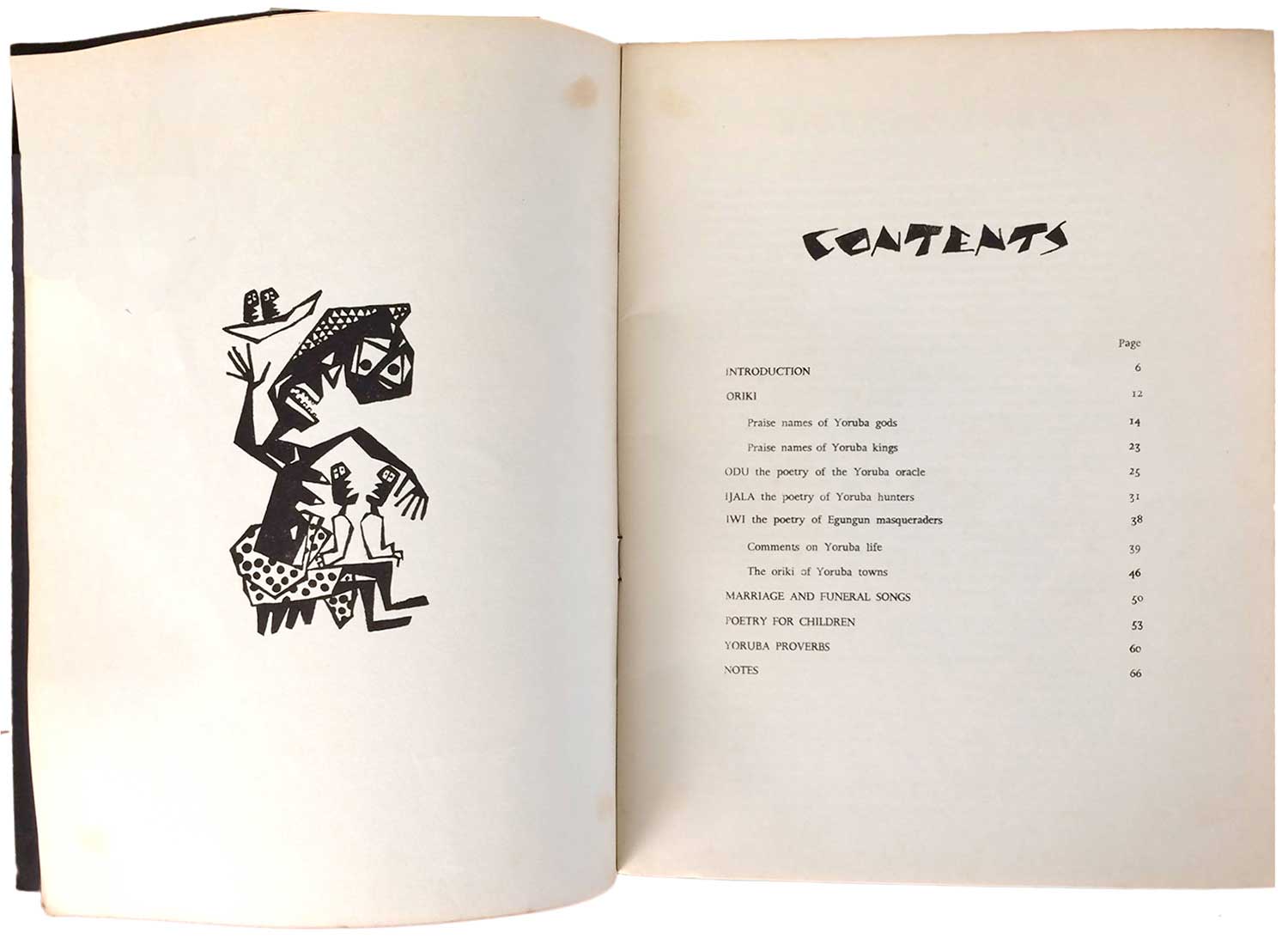

Unfortunately copies of Black Orpheus are relatively hard to come by, and when I first stumbled upon them you could pick one up for $10-$20 here and there. Now there more likely $30-$50 each, and harder and harder to find. I’ve been able to pick up five issues, and taken photos of a couple more from friends. The rest here are an amalgamation of images I found in different places online—many took considerable cleaning up to them into presentable shape. From top to bottom we’ve got issues 1; then 2 (I believe), 4, 6; then four inside pages from 6; then 7, 8, 9; 10 & 11; 12 & 13; and their numbered from there on. Issue 20 the “Special Yoruba Poetry” issue, and I’ve included some images of the really nice 2-color internal illustrations. I haven’t ever seen any copies of issues from volume 3, and I can’t find any images of them online.

Below are the two editions I have from volume two. They are similar in size and design, although a little thinner, clocking in at 46 and 50 pages, while almost all of the issues of volume one were 64 pages. The editorship is now in the hands of J.P. Clark (Nigerian poet and playwright) and Abiola Irele (Nigerian academic), and the tagline has been changed to “A Journal of the Arts in Africa.” In addition, the covers have a similar aesthetic but are designed by the Nigerian artist, architect, and stage designer Demas Nwoko.

It seems worth noting that as far as I can tell there was never any women on the advisory committee and almost no women contributors beyond Susanne Wenger and a couple academics writing criticism about male authors.

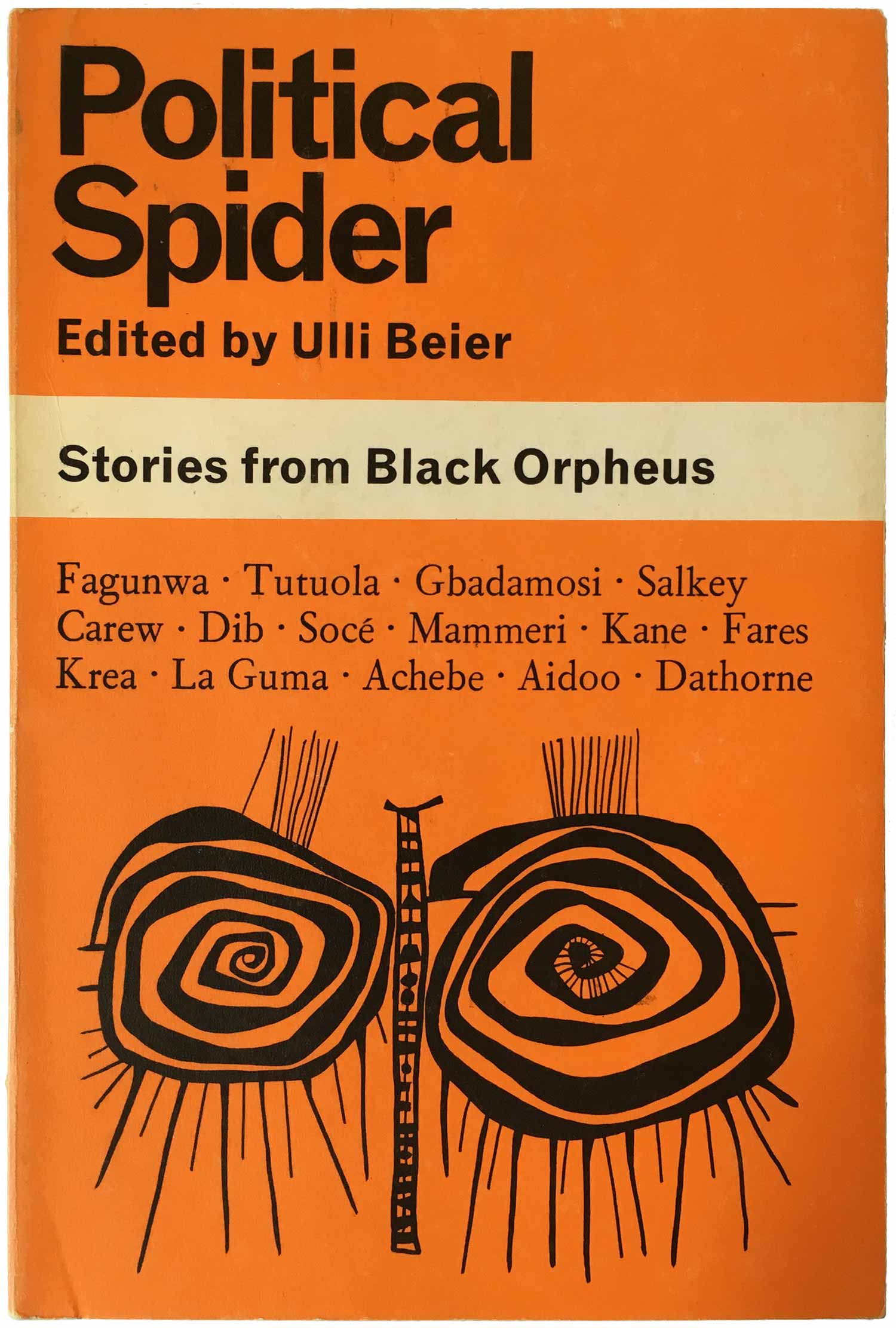

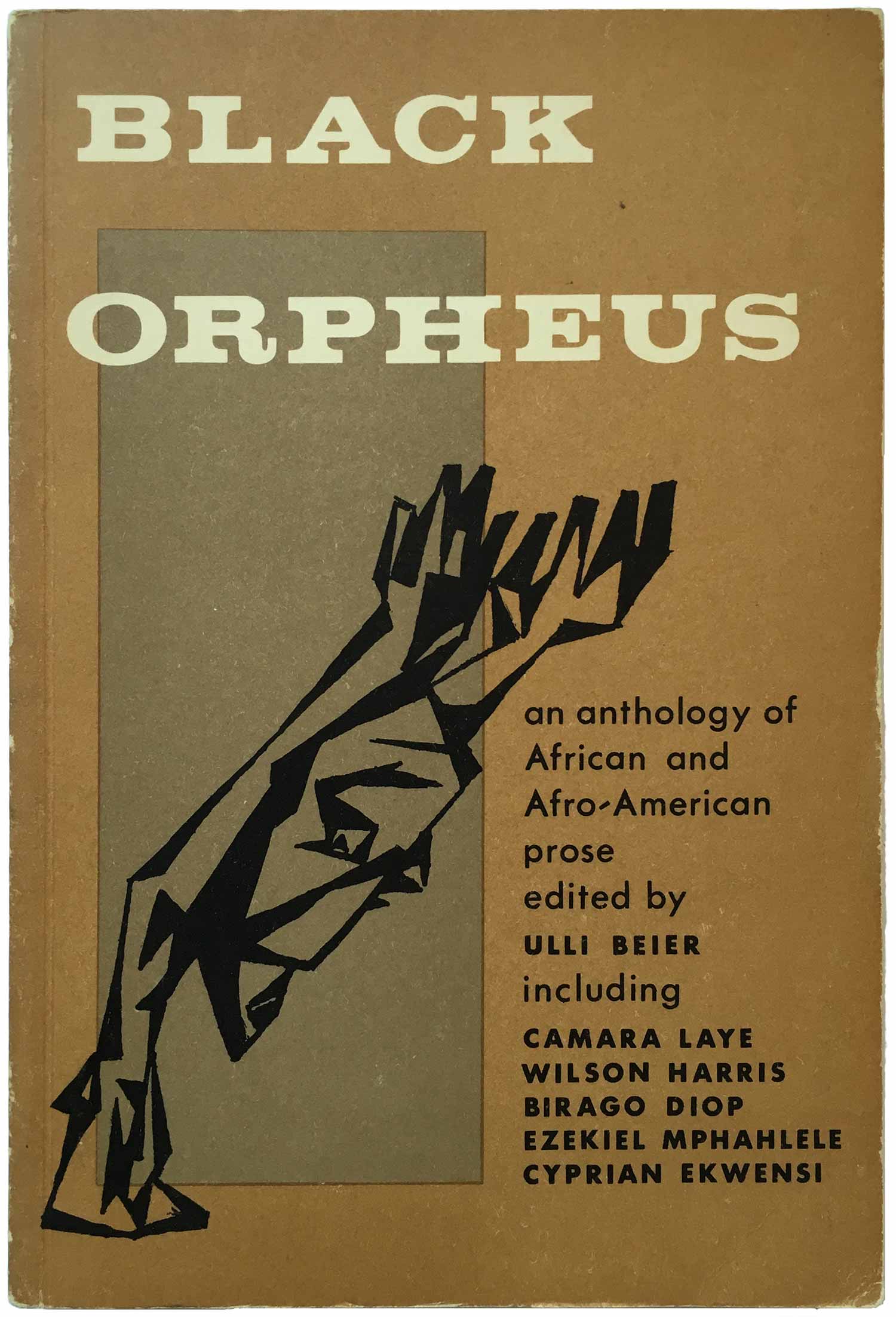

Below are two of the three (at least) collected editions of writings from Black Orpheus. To the left is the earliest, published in 1964 while the first volume was still coming out. It was put out by Longmans of Nigeria, one of the main African wings of the mainstay British publishing house Longman. (British publishing roughly followed the routes of British colonialism, setting up local offices across much of the British Empire, in particular India and Anglophone Africa.) Although forgoing the logotype, the cover otherwise is roughly modeled on the design of the magazine, sticking to three colors and re-purposing the graphic Wenger designed for issue 4. To the left is Political Spider, a later compilation published as part of Heinemann’s long-running African Writers Series. This cover features a graphic from Georgina Betts (Beier’s second wife) pulled from an issue of the magazine, but otherwise the design speaks more to the African Writers Series than Black Orpheus itself. (Far more to come on Heinemann’s AWS! I’ve been collecting and researching them for years, and now it’s more an issue of finding the time to put together a 200+ cover series than anything else.)

Next installment we’ll look at the output of Mbari Publishers, with lots more amazing artwork from Susanne Wenger and others.

This is a bibliography of the issues and books I own. I unfortunately don’t have full bibliographic information on the other issues: