Here is an excerpt from my book A People’s Art History of the United States. This excerpt details the woman’s suffrage movement in the late 1910s and their use of banners. More over, it details the NWP’s use of civil disobedience and banners to escalate the conflict and force the federal government to act – often in repressive ways that created more press for the movement.

Banners Designed to Break a President

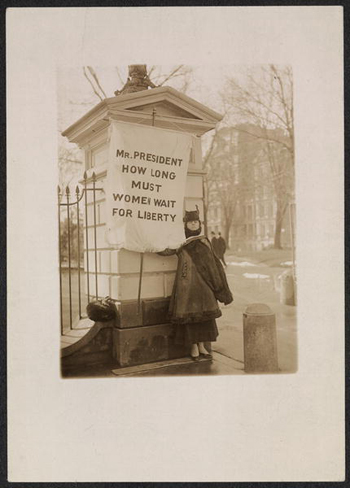

On January 10, 1917, the National Woman’s Party (NWP) initiated the first-ever long-term picketing of the White House. Twelve women, led by Alice Paul, went to the east and west entrances in the midmorning, where teams of three stood silently by each side of the two gates. Dressed in all white, they stood with two four-by-six banners attached to long poles. One banner read: MR. PRESIDENT, WHAT WILL YOU DO FOR WOMAN SUFFRAGE? The other: MR. PRESIDENT, HOW LONG MUST WOMEN WAIT FOR LIBERTY? President Woodrow Wilson reacted as the women hoped he would when he passed by in his motorcade. He was surprised, and unnerved that well-dressed, middle-class women would stand in the cold and picket his residence. His response was to invite them in for hot tea. The women refused. The next day more women from the NWP returned with banners. One featured the quotation “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.” Susan B. Anthony had said this to a federal court in 1873 when she was tried for attempting to vote. The White House pickets would continue for the next three years. Doris Stevens summarized their effect: “What politicians had not been able to get through their minds we would give them through their eyes . . . Our first task seemed simple—actually to show that thousands of women wanted immediate action on their long delayed enfranchisement.”

Silent Sentinels

“We have got to keep the question before him all the time.”

– Harriot Stanton Blatch

The National Woman’s Party (NWP) escalated its tactic of standing next to the White House gates with banners after their first “silent sentinel” on January 10, 1917. The first banners had been relatively polite, but that approach soon dissolved. The NWP began instead to mock Wilson with his own words. They reprinted phrases from his war speeches that showcased the hypocrisy of his support for democracy abroad while failing to support it at home.

On June 20, 1917, a representative of the new Russian government visited the White House. Outside the gates, Lucy Burns, Dora Lewis, and others stood with a large banner.

To the Russian Envoys ,

President Wilson and Envoy Root are deceiving Russia when they say “We are a democracy, help us win the world war so that democracy may survive.”

We the women of America tell you that America is not a democracy. Twenty- million American women are denied the right to vote. President Wilson is the chief opponent of their national enfranchisement.

Help us make this nation really free. Tell our government it must liberate its people before it can claim free Russia as an ally.

On June 22, Burns and Katherine Morey were arrested for “obstructing traffic.” Three days later, twelve more women were arrested for carrying banners. In court, the women were ordered to pay a $25 fine; they refused and spent three days in jail. When one group of six women was brought before the court, one responded by stating, “Not a dollar of your fine will we pay. To pay a fine would be an admission of guilt. We are innocent.” From that point on NWP women began to fill the jails.

Wilson detested the tactics of the NWP and the press attention that they received. His secretary and political aide Joseph Tumulty called for a partial press blackout of the pickets, pressuring Washington-area newspapers to keep stories on the NWP to a minimum. Many obliged. The Washington Post refused.

The Russia banner also enraged conservative suffragists. National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) president Anna Howard Shaw wrote to Dora Lewis in 1917 and accused the NWP of treasonous activity. NAWSA printed objections to the White House pickets in 350 papers across the United States. Carrie Catt went a step further. She would at times notify the White House of planned embarrassments by the NWP.

Despite their detractors, the NWP stepped up their agitation. They followed a pattern of escalation: pickets, jail time, and capitalizing on the press that their actions received. In July and August of 1917, Wilson finally attempted to break this cycle by calling for an end to the arrests and consequently the press attention. So Paul, in turn, upped the ante. The NWP created a banner that compared Wilson to the enemy, German Kaiser Wilhelm II. One banner read: For 20,000,000 AMERICAN WOMEN WILSON IS A KAISER. This created an uproar. Woman who held the banners were attacked. Paul was knocked down three times, and on one occasion she was dragged the length of the White House sidewalk by an enraged sailor. After each attack, Paul sent out a press release detailing what had transpired.

The courts responded to these new tactics with longer jail sentences. Women were charged with a $25 fine or sixty days in prison at the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia. Those arrested were charged with obstructing traffic and were denied the right to a trial by jury. Instead, they were sent to prison and housed with the general population.

On October 20, Paul and three others left the NWP office with a banner carrying a phrase that the Wilson administration had used on a poster for a Second Liberty Bond Loan: THE TIME HAS COME WHEN WE MUST CONQUER OR SUBMIT. FOR US THERE CAN BE BUT ONE CHOICE. WE HAVE MADE IT. Paul was arrested and sentenced to seven months at the Occoquan Workhouse.

Jailed for Freedom

“Things took a more serious turn than I had planned but it’s happened rather well because we’ll have ammunition against the Administration, and the more harsh and repressive they seem the better.” —Alice Paul, letter to Dora Lewis from prison, 1917

When Paul arrived at Occoquan, she initiated a hunger strike. Fourteen other women joined her. Each was force-fed three times a day—an extremely painful procedure in which a hard tube is placed down one’s throat and food is deposited into the stomach against one’s will. All of the NWP women who were jailed refused to work. They also demanded to be classified as political prisoners, a demand that was denied.

Paul received particularly brutal treatment. She was placed in solidary confinement and, eventually, a psychopathic ward—a terrifying prospect, considering that prisoners in this ward could be held indefinitely. Paul, however, recognized the tactical advantages of her harsh treatment— news of the force-feeding and the horrid conditions of the prison resulted in a public outcry and greater approval for the suffrage cause.

Still, the government would not relent. NWP activists in Washington, DC, who demonstrated against Paul’s treatment in prison were arrested and also sent to jail. When they entered Occoquan they endured a “Night of Terror” when the warden instructed more than forty guards to brutalize the women, by beating, kicking, choking, and dragging them across the jailhouse floor.

On November 23, many of these same women were brought before a judge. In the courtroom, the press re- ported on their poor conditions and noted that many were too weak to stand or sit. The judge ordered three women immediately released due to their ill health.

By the end of 1917, the movement was taking a toll on the women, but it was also taking a toll on Wilson to the point where he changed his position on woman’s suffrage. He spoke out in support of a federal amendment for the first time and lobbied his colleagues to do the same. In January 1918, the amendment passed the House 274 to 136. In June a filibuster by Democratic senator James A. Reed of Missouri prevented a vote in the Senate.

The NWP decided to keep a watch fire (an urn) lit in Lafayette Square as a reminder to Wilson, and to themselves, that they would not quit until an amendment was passed. There, the demonstrators burned copies of Wilson’s speeches and burned an effigy of him in protest. More arrests followed. Paul, Burns, and others were sentenced to ten to fifteen days in prison and placed in underground cells that had been deemed too unsanitary for the general prison population. The women initiated a hunger strike and were released after five days.

During the fall of 1918, a federal woman’s suffrage amendment failed to pass the Senate, but it finally succeeded in 1919. On May 21, the House passed the amendment 304 to 89. On June 4, the Senate passed it 56 to 25. From there, the constitutional amendment needed three-fourths of the states to ratify it. The NWP then focused their attention away from Wilson and directed their campaign toward the states where votes were needed most. By March 1920, thirty-five states had ratified, and the struggle came down to Tennessee. The close race was decided when Harry Burn, a twenty-four-year-old legislator, changed his vote in favor of ratification at the insistence of his elderly mother. In August, Tennessee would ratify. In celebration, the NWP hung a ratification banner outside its Washington, DC, office.

http://peoplesarthistoryus.org/

http://justseeds.org/nicolas_lampert/03pahbook.html

Also: I will be in NYC, Baltimore, and Philadelphia giving book talks from January 8th – 12th. To see the schedule of talks, click here.