Here is another excerpt from my book A People’s Art History of the United States. This excerpt details the feminist art movement in California and specifically the Woman’s Building – an epicenter for activism and art in Los Angeles from 1973 to 1991 and the home of the first independent art school for women.

In researching the chapter, I was reminded just how important collectively run spaces and experimental cultural spaces are for nurturing a culture of resistance and for fostering collaboration. These types of spaces produce activism. How many people were transformed by the LA Woman’s Building during its near two-decade run? Likely thousands. Its legacy matters. Its influence is felt.

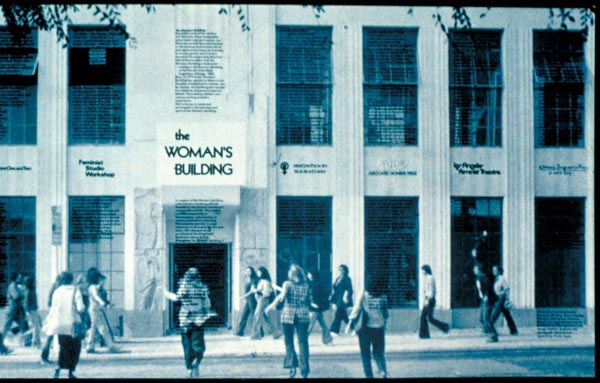

The Woman’s Building

In 1973, Judy Chicago resigned from CalArts to form the first independent art school exclusively for women—the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW)—in collaboration with the graphic designer Sheila de Bretteville and the art historian Arlene Raven.

Together, they chose the former Chouinard Art Institute—on 743 South Grand View Street, near MacArthur Park—which had fallen into disrepair and was owned by CalArts, which rented it to them for $3,000 a year.

On November 28, 1973, after months of carpentry, painting, and repairs, a new epicenter for feminist art and activism—not to mention a model for alternative art spaces and art education— opened. Named the Woman’s Building after the Woman’s Building Pavilion at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, it housed the FSW and two other women’s art education programs, the Extension Program and the Summer Art Program.

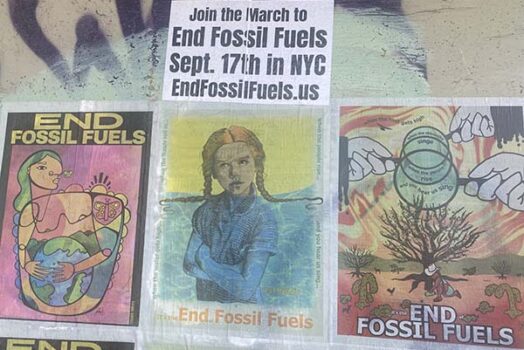

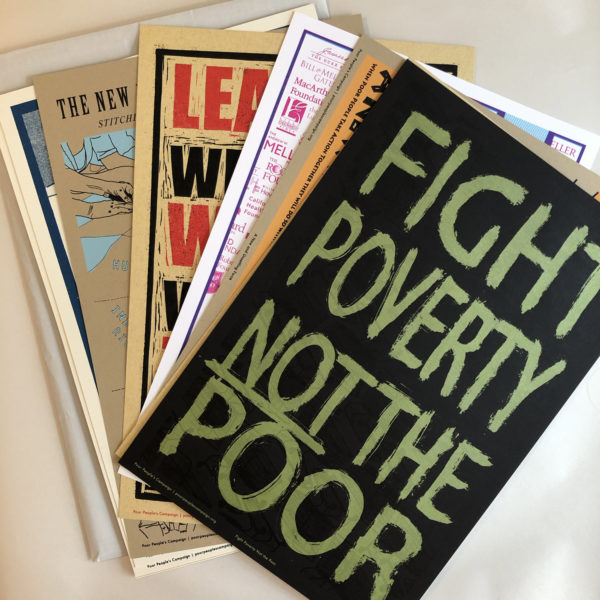

It also housed the Women’s Graphic Center, run by Sheila de Bretteville and Helen Alm, which featured offset li thography presses, silk- screen, letterpress, and other printmaking tech niques for creating broad- sides, posters, newsletters, and artists’ books; women- owned businesses (Sister hood Bookstore and the Associated Women’s Press, among others); seven galleries, including Grandview I and II, the Community Gallery, the Open Wall Show, the Upstairs Gallery, the Floating Gallery, and the Coffeehouse/Photo Gallery; performance-art spaces including Woman’s Improvisation and the Performance Project; and activist groups, including the Los Angeles chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

For two years, the Grand View location became a hub of activity. Exhibitions, performances, lectures, readings, and workshops took place nearly every day of the week. Women—primarily white, middle-class women—from across the country enrolled in the FSW and immersed themselves in the activities of the Woman’s Building, training in new media, graphic arts, and feminist art (painting and sculpture classes were not offered).

Projects and groups that formed at the Woman’s Building during the 1970s included Mother Art (a space that welcomed women artists and their children), the Waitresses (a performance group confronting sexism in the workplace), the Lesbian Art Project (whose groundbreaking work included the performance An Oral Herstory of Lesbianism), and Ariadne: A Social Art Network (that connected women artists, collectives, and activist groups across the country), among others.

This separatist space and separatist feminist movement was needed. Women artists and designers were not deemed equal in the art world and the workforce. In the early 1970s, the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists reported that out of 713 artists who exhibited in group shows at the Los Angeles County Museum only 29 of them were women. Out of 53 solo exhibitions, only 1 was a woman’s.

The Woman’s Building and the FSW supported women artists forging their own paths. It supported collectivity and collective action. All decisions at the Woman’s Building were made by a council that included one member from each group and tenant in the building. Cheri Gaulke writes, “Collaboration was a means of production, but at its best, it was also the living, breathing embodiment of a culture transformed. In many ways it represented our utopian vision of the world, where people were truly equal and everyone’s contribution was valued.”

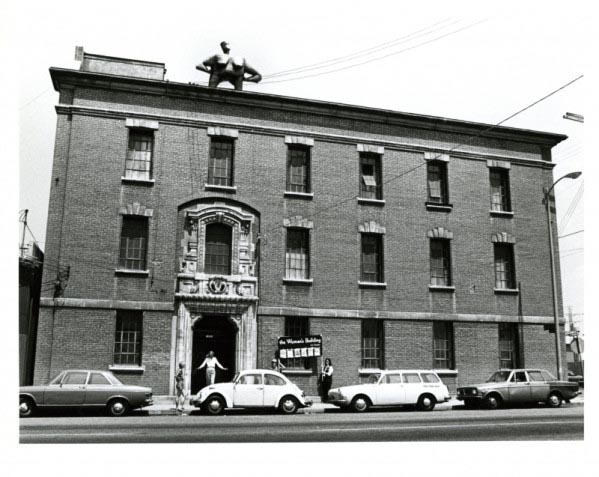

Judy Chicago, whose vision helped create the Woman’s Building, left after the first year to focus on her own individual art career. Nonetheless, others carried forth the organizing efforts; the Woman’s Building allowed the alternative art space to become larger than any of the individuals involved. People could come and go and bring forth new ideas and new energy. The pressures of maintaining the space, however, were notable. In 1975, CalArts sold the building and the new owner ended the lease. Undeterred, the Woman’s Building, along with the FSW, moved to North Spring Street in an industrial corner of downtown Los Angeles.

Internal group pressures also took a toll. In 1976, Arlene Raven wrote to Sheila de Bretteville, “Somehow I feel the need to feel like a separate person instead of a cog in our group/organizational wheel, marching as I have been these last years to the sound of what I think is my duty . . . I love what we’ve built even though its maintenance is burdensome.”

Raven’s quote summarized the highs and lows of collective practices: the sacrifice of individual needs for the group’s benefit, and the intense amount of work needed to keep these types of spaces running, often on little funds and donated labor.

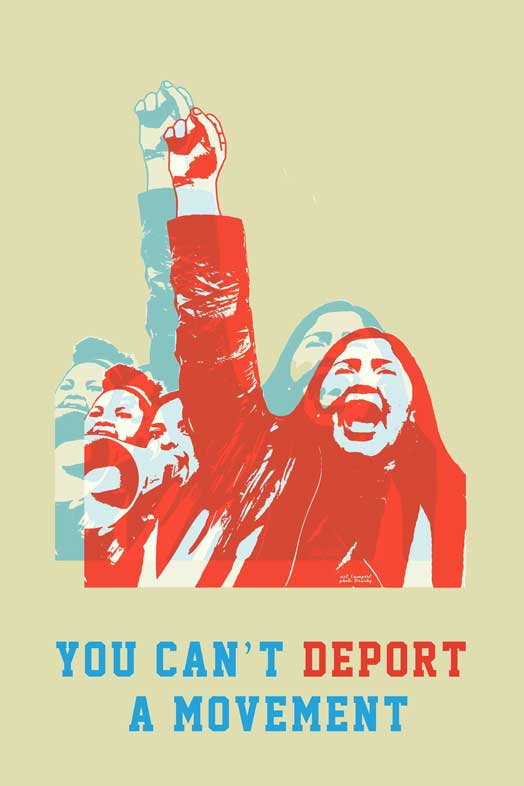

In the early 1980s, low enrollment ended the FSW and forced the Woman’s Building to alter its course once again. More space was carved out and leased to other groups to help pay the rent. Moreover, the focus of the Woman’s Building shifted toward coalition-building and global solidarity movements. While the 1970s called for a much-needed separatist movement that nurtured and empowered women, the 1980s demanded new tactics. President Ronald Reagan’s two terms in office ushered in a nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, a covert war against leftist movements in Central America, the start of the mass incarceration of Americans – especially people of color (the War on Drugs), a roll back on environmental protections, and an attack on unions. In general, Reagan’s policies represented a hyper-privatization of the public sphere that led to drastic de-funding for public education and public services at the federal, state, and city levels. Cultural spaces were hit hard and had to scramble for funding. Furthermore, these policies embodied an affront to the gains made by the feminist and multicultural movements of the 1970s.

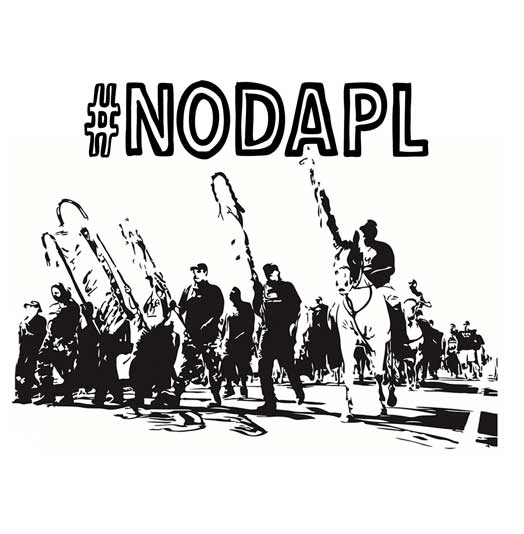

The Woman’s Building responded in kind. The Sisters of Survival, a group that challenged the impending threat of nuclear war, formed in 1981. The Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador also moved into the Woman’s Building, bringing men and more minorities into the space, something that had been lacking during the 1970s.

In 1991, the Woman’s Building project came to an end. Its influence, however, was felt by the tens of thousands of people who had passed through its doors as students, instructors, performers, artists, and visitors. It influenced an untold number of artists’ groups and spaces that formed during and after its incredible run. Cheri Gaulke reflects, “We were concerned with changing the lives of real women through our art, our activism, and our very organizational structures.” The Woman’s Building, along with Womanhouse and the Feminist Art Programs, achieved this goal; they each served as a safe space where a separatist movement could be nurtured, as well as critiqued and expanded upon.

Learn more about the Woman’s Building history:

http://www.womansbuilding.org/

The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact, Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, eds. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1994)

Faith Wilding, By Our Own Hands: The Women Artist’s Movement, Southern California 1970– 1976 (Santa Monica: Double X, 1977)

Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building, Meg Linton and Sue Maberry, curators (exhibition catalog, Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, 2011),

http://peoplesarthistoryus.org/

http://justseeds.org/nicolas_lampert/03pahbook.html