My friend Daniel Drennan in Beruit was recently interviewed on the Design Altruism Blog. He is a member of the artist/design collective Jamaa Al-Yad (who contributed a poster to the recent Occupied Wall Street Journal poster edition). The interview is a good read, so check it out HERE. Here is a taste:

NC: How do you view people’s enthusiasm for creating illustrative graphics for left-leaning causes today in Lebanon? I would think this has changed or calmed down over the last couple of years in Lebanon from the situation around 2001-2007, during the inner turmoil with political issues, and the effect of Bush, Iraq, and Sept. 11, 2001. How has it changed?

DD: Lebanon is a very particular case; we have to examine it in terms of its political and economic history. There is no history to this country other than one framed along neo-liberal economic lines; meaning, the governmental, legal, educational, social, and cultural systems existing here work within an economic model that has always been purely capitalistic and serving comprador and foreign interests. Period.

Unlike our neighbors going through various revolutions, there has never been an official government or “regime” here that advocated for, say, socialism, or Pan-Arabism, or a break with foreign interests. So the left-leaning causes end up being centered elsewhere, and they resonate back here, especially in terms of specific industries, like publishing. But when they actually managed to gain strength and popular support, they became targeted. The destruction of the left-wing coalition that went up against the local system and acted in a resistant capacity wholly outside of this mode gave us the civil war. This has not been recovered from yet.

Just like in the United States and most of the First World, Capital has co-opted the left and progressive elements if not eliminated them; on the flip side we have an imposition of a mindset that has segments of the population claiming to be “progressive” but who do not want to give up their bourgeois privilege as guarded and protected by this entrenched system. So in terms of creative output there might currently be a bit of barking, but it is safe and within limits; there is certainly no bite, especially of the hand that feeds them. And what you notice is that the expression is well within the parameters set by these economic systems: In foreign languages, aimed at foreign media/NGO audiences, or placed online or in particular media outside of the reach of the street. During the election campaigns and after the war in 2006 you notice a shift to the advertising realm away from what was formerly expressed on the street. So it’s not so much a calming down, but an effective “defanging” of popular expression.

NC: In terms of local illustration, we have had editorial strips, civil war/political posters, and recently more subversive or online local comics that used illustration as means to go against something or somebody, and to satire, support, or propagandize political issues. Do you feel that there is a large gap between the situation here in comparison with that in modern non-western countries, Arab or otherwise, who have developed more of a base? If so, in what way?

DD: The gap is certainly not between what we might wrongly refer to as “East” and “West”. There has always been an active graphic tradition, but it has settled into a more or less sectarian mode, where graphic production is for a local party that oversees a given neighborhood or community as opposed to a given grander ideal. This insularity is not necessarily a fault of individuals, but a desired and incentivized fragmentation from above of political actors on the local stage. I would differentiate though between what was traditionally and historically produced in terms of posters, coupled with printers and other disseminators and communicators who were all of a decidedly populist nature, and what is found in the online realm today, along with the English- and French-language publications that are, on the contrary, elitist in nature and in content.

To be considered here are aspects of a framework that we use in our collective to analyze any manifestation along these lines. Namely, the artist involved, what is her ability and right to speak? What is her luxury or privilege beyond that to say what she wishes? Finally, what audience is she speaking to, in what medium, via what venue, at what cost? If I am of a class removed from the street, and I am publishing cartoon strips in an online realm removed from the majority of the population’s ability to access them, in a language foreign to them beyond that, who am I serving? If I bring Emory Douglas into the Beirut Art Center and charge fifty dollars to participate in a workshop with him, who am I serving except my own class vanity? This isn’t subversive; this is playing “edgy” with one’s class status, this is slumming it. This is a completely different from publishing subversive work or expressing oneself subversively.

I would also be careful of using the word “modern.” Things aren’t “backwards” here; they are in fact refreshingly active if one can step down from one’s class position enough to notice. The so-called First World is the one which has gone stagnant, now that it has exported its local printers’ trade and craft, co-opted and destroyed any concept of local media, and has replaced true activism with a disturbing post-modern version that would have us accept our condition as a given, with minor divergences from this somehow labeled “resistant”. This shift in focus is a function of Capital, where dissent is allowed within the parameters of the system itself. It should be seen for what it is, and resisted at all costs.

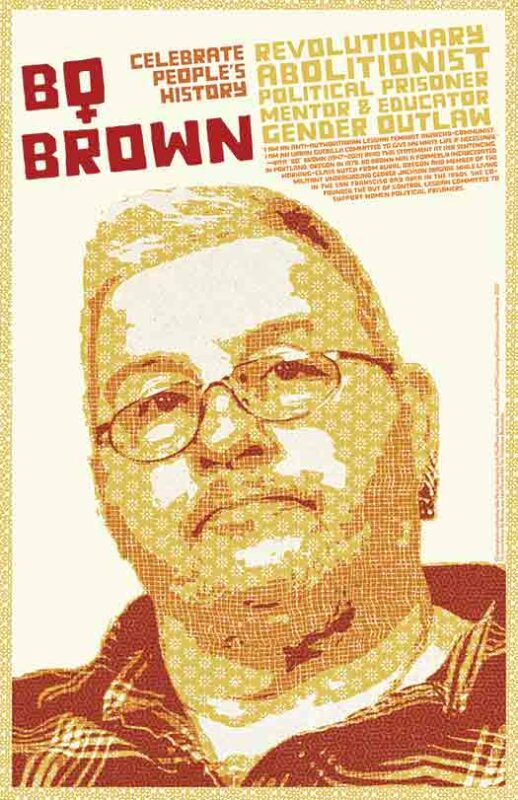

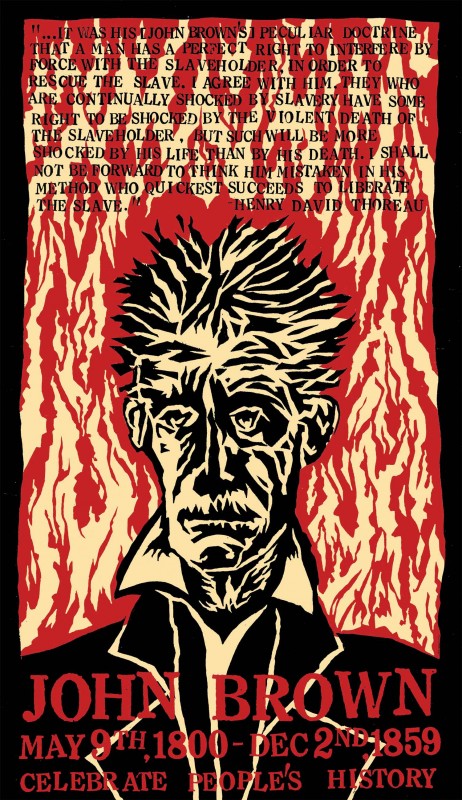

image above: Series of four posters for the Return to Palestine March, May 15, 2011. Artist: Jamaa Al-Yad