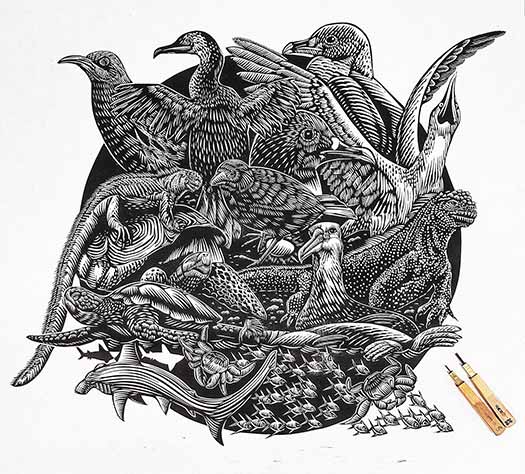

I was recently interviewed by Jeanne Dodds at the Endangered Species Coalition about the mural project I’ve been coordinating for the past four and a half years. See the full post there at this link.

Jeanne Dodds, Endangered Species Coalition What inspired the Center for Biological Diversity to initiate a series of murals depicting endangered species?

Roger Peet, The germ of the idea for the project came when Noah Greenwald, the Center’s Endangered Species Director, was visiting Sandpoint Idaho to do some work on the dwindling herd of Mountain Caribou that lived in the mountains nearby. While discussing the plight of these animals with a city council-member, the thought emerged that it was a pity that there was nothing in the town of Sandpoint to alert residents to the fact that there was this population of distinct, dramatic, charismatic and highly endangered mammals roaming the high peaks that are visible from town. The city councilperson opined that someone could paint a mural or something, and Noah, with whom I’d worked on several art projects for the Center and who was familiar with my work as an artist and muralist, thought: I know someone who could do that. We talked about the prospect of painting a mural, and agreed that we should try to paint more than one, to see how many we could create and how far we could make the idea go.

JD What are the goals for the mural project?

RP Generally my response to this question is to say that we are trying, through these murals, to communicate about something that makes a place unique; the endangered species that inhabit different regions and communities across the country are part of what makes those places special, and are a part of the fabric of civic and environmental life and culture. Their loss would mean that the place where they were once found is much diminished, and that the people who live there have lost something that helped to define their home as somewhere different, a place with its own quality, character, and history. Species connect us to each other, and to deep time, and their loss impoverishes us all in novel and depressing ways. By celebrating them we help to celebrate ourselves, and to imagine our communities as whole places that value every part of the landscape and ecology that encompasses them.

JD What do you hope that the audience for this work takes away from seeing these murals?

RP My most basic hope is that they are inspired to learn more about the species that surround them, and in so doing acquire a deeper and more basic sense of themselves as part of a larger world, a larger biological context which is worth identifying with and worth defending. Beyond that I hope that people are driven to get involved in the transformation of their communities and societies, finding new ways to live in the world that do less damage to the land, water, and air that we depend on, developing new sets of responsibilities that they take seriously and teach to each other, to their children and to their parents.

JD What kinds of responses have you heard from individuals or groups viewing the artworks?

RP Well, painting a mural is pretty good for the ego- people walking by are generally pretty complimentary and as a mural progresses the comments get more and more enthusiastic. It’s always heartening to see young people interacting with these works, and especially so when they understand right off the bat what we’re trying to communicate. As a rule I think young people are more receptive to the ideas that we’re promoting, and are a really core audience that picks up what we’re laying down. Walking away from a finished mural in Cottage Grove, Oregon last year I saw a line of middle-schoolers walking past it and touching it as they passed, looking up at the image and stopping to read the explanation next to it. That felt like success.

JD What do you see as the value of art in communicating about biodiversity and species conservation?

RP Art can do a lot of things, but not everything, and it’s important to recognize that and to consider when art is useful in trying to achieve a result, and when another tactic might be better employed. For communication purposes, art does a pretty good job, and static pieces like murals can serve as landmarks and subjects of conversation over time. Art also confronts people with ideas that they might not like or that they might not initially identify with, and while it’s always best to consider a community’s sentiment when installing a work like this, a mural can serve as a way of stating a position, and create a line in the sand which helps people defend their points of view. One thing that I’m personally really interested in doing with my art is not to say that these species are sacred or to be venerated, but that they are a part of us, part of our daily lives, and deserve our respect and consideration.

JD As an artist, can you describe the creative process in developing and realizing a completed mural?

RP Each of these murals starts from the point of finding an appropriate wall. Once we have one in our sights, and have worked with the scientists and organizers at the Center to identify a candidate species that we’re hoping to represent, I or the other artist creating the mural will do a sketch of a design to be shown to all the parties involved in the project. If the idea meets with approval a more detailed design is created to summarize more precisely how the finished mural will look. Once that’s approved and everyone is one board we schedule a date to paint. At the site we clean and prime the surface and then trace the design onto it, either via projection or by gridding the surface with chalk line. Then we paint, usually filling in large areas of color first and then working back into it with more colors and more layers until we’ve covered the entire surface and are touching up the small details. We’ve learned a lot about different ways that murals go up, including a novel technique that involves painting the mural on a polyester substrate like the material that’s used to stiffen shirt collars (and comes in 5 foot wide rolls about 200 feet long) and then adhering it to the wall with a gel medium. This method is really great because it allows us to work indoors when it’s super hot, and also to take the mural into schools and allow students to work on it without the complication and hassle of getting them out to the site itself. Once we’re done we apply some sort of protective medium to protect against UV or less likely, graffiti. We’ve found that murals are broadly respected by street artists and don’t necessarily need a lot of protection, however. When we’re completely finished with all of these details we host a party, inviting local scientists, students and organizers as well as community members to help us celebrate the finished object, usually with music and snacks.

JD How can people become involved with this project to create a mural in their community?

RP Help us find a wall! The hardest part of this project is finding an appropriate place to paint, somewhere with good year-round pedestrian exposure, a nice smooth surface in good shape, and with an owner willing to leave it up for five years. Unfortunately we’re never going to lack for subjects, so we will go anywhere we can find a bit of funding and a wall to paint on. We rely on local partners to help us find places to paint and to connect with the communities where these murals are created, and building those relationships is a really important part of the project.

JD What actions can people take to support conservation of the species depicted in the murals?

RP Staying educated and staying involved in local environmental politics is always important, and there are local organizations almost everywhere working to defend species and their habitat. If you can’t find one, maybe you could start one!