Josh MacPhee is one of those people who are difficult to categorise. He’s an artist, an author, a zine maker, radical, and a curator pretty much all at the same time! He established a novel distribution network called Justseeds back in 1998 with the intention of getting more radical art projects out to the public. Over the years it has grown and morphed and is currently an artists collective known as Justseeds Visual Resistance.

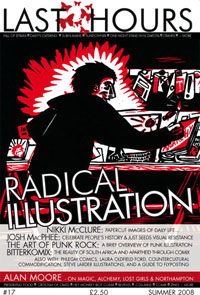

He has also published a number of books, most recently Realizing the Impossible, which he co-edited with Erik Reuland. His book I first encountered though was Stencil Pirates back in 2004, which my friends and I returned to fitfully during that hot summer as we explored our city with our spraycans. I met him, almost by accident, at 2007’s anarchist bookfair where he had a table hidden in the back of the hall. Early in 2008 I finally sent through some questions about Justseeds, radical art, the Celebrate People’s History poster project he established and some of his future projects he’s working on.

Last Hours: To start from the beginning how did you get involved in creating artwork, was it something you were always interested in or something that developed. Likewise what led you to become interested in radical politics? Were you always interested in creating ‘political’ art or did one proceed the other?

Josh MacPhee: Both my parents are teachers, and my Dad was a high school art teacher (recently retired). I grew up around art and books, and art books! I started making art at a really early age, and just never stopped. I don’t have a ton of formal training, art was never something I thought of as a career. I didn’t go to art school, it’s just something I’ve always done. At some point I realized art was the thing I enjoyed doing most in life, and I should figure out how to spend as much time as possible doing it.

As for politics, I became interested in anarchism through reading books in grade school (I remember my parents giving me Emma Goldman’s Living My Life for my birthday once). I became more directly politically aware about the larger world around me when the US invaded Iraq back in 1990/91, the first Gulf War. It didn’t make a ton of sense, and if you interrogated the official US reasons for the war, they unraveled pretty quick.

It was at this time that I first came in contact with World War 3 Illustrated and Punchline magazines. World War 3 is a political comic book that was started back in 1981, but in the late 80s, early 90s, they had a couple issues about the Gulf War. It was here that I was first introduced to artists like Seth Tobocman, Peter Kuper, Sue Coe and Anton Van Dalen, and more specifically to the use of stenciling for political art. Punchline was a zine created by John Yates, a political designer who was really involved in the California punk scene (and ran Allied Records). Each issue was a themed compilation of single pages designed, drawn or collaged mini-posters, seemingly created to be thrown on a photocopy machine and reproduced, then pasted up on the street. Both these publications opened my eyes to people struggling with what the fuck was going on in our messed up world through art, and I was hooked.

Why did you choose to work with printmaking and stencils?

Before starting with stencils or any traditional forms of printmaking, I was making photocopy art. In 1988 or ‘89 I started making weird zines with my friends. I had one friend whose parents owned a franchise of an insta-print photocopy store, and we used spend weekends in there fucking around with the machines, blowing images up, shrinking them, piecing together pages. We’d make an issue of a zine and then run dozens of copies off, then hand them out at school. I was always attracted to the ability to make multiples, to be able to get them into the hands of lots of different people.

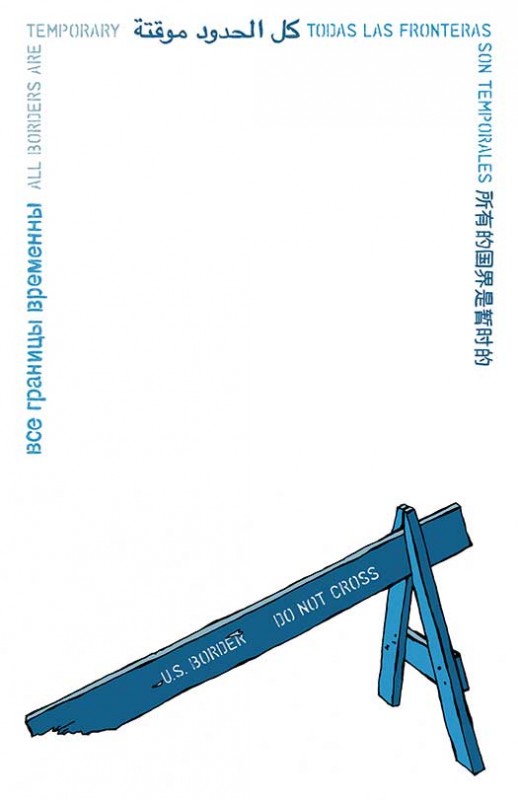

Stencils and silkscreening just follow from that. It’s all about being able to make and distribute a thousand of something, to get as many people as possible to see it. I’m interested in spreading ideas, and we live in a mass society, so I believe in the mass production of the vehicles of ideas, whether that’s in the form of street stencils, offset printed posters or photocopied magazines.

Along this same idea I’m just finishing up a new book with Favianna Rodriguez, which is a collection of 500 reproducible political graphics for activists to use. It’s called Reproduce & Revolt, and should be out on Soft Skull Press in the next couple months. The graphics are from around the world, and are all Creative Commons licensed, so that activists and organizers can use them far and wide, and we can more graphics injected into our collective radical bloodstream.

What was the inspiration behind establishing Justseeds? Had you worked on any similar project before?

I started Justseeds back in 1998 as a way to distribute the political art I was making, which at the time was mostly political t-shirts. I started with a small mail-order catalog (one sheet of paper, really!) that I distributed to bookstores and infoshops and such, and also sent out to friends, and slowly people started ordering stuff. I added posters and some zines, and then created a basic website, and by 2004 it had grown a little too big for my tiny apartment.

To make a long story short, some friends were running an online store, and they offered to take over filling all my orders for me, since they already had a small working warehouse set up. That allowed me to expand Justseeds to include work by other like-minded artists, and turn it into a place people could go to find all kinds of political art. This worked well for a couple years, but then my friends had some financial troubles, and had to shut down.

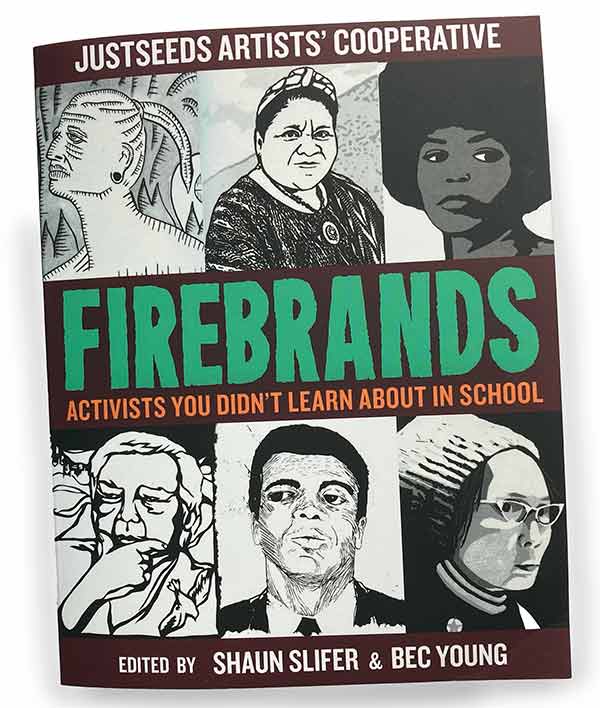

I couldn’t take the whole thing back into my small apartment, I didn’t have the space or the time, but I didn’t want to shut the whole thing down either. What ended up happening was a number of the artists whose work I had been distributing were interested in turning Justseeds into a artists’ cooperative. Now there are about 20 people involved in some capacity, we all have equal ownership and decision making in the operation, and we try to share all the labor as best we can. That’s how the Justseeds Visual Resistance Artist’s Cooperative was born!

We’ve now got over 200 items up on the site, as well as run a political art blog that we all post to, pulling together a ton of information about the political end of what’s going on in the world of art and culture, and the cultural end of what’s going on in politics.

Was the ‘Celebrate People’s History’ poster project started at around the same time? What led you to starting the project?

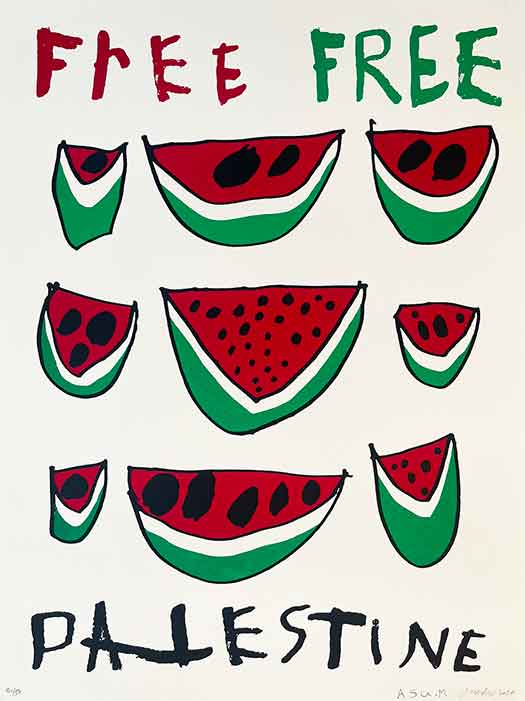

The People’s History posters were started around the same time I started Justseeds, 1998. The CPH project came together from a whole set of impulses: First, I had just recently moved to Chicago, which is the third largest city in the US. I had never lived in a place as big before, and definitely not a place so completely covered with advertisements and public messaging. Such a big city is a target market for just about everything, so every single movie, record, fast food restaurant and big chain store has advertisements up everywhere, from giant billboards to small wheat pasted posters on boarded-up buildings. On top of that, Chicago has a thriving independent culture, so there are also tons of small bands, record labels, art galleries and clubs posting up advertisements on the street, as well as political groups and social clubs. In some neighborhoods every square inch of space was covered, which I found exhilarating, but also kind of intense considering that all the messaging was directives, attempting to tell people what to do; buy this, go here, do this. What I wanted to do with the CPH posters was to put something a little more generous out on the street, something attractive and interesting to look at that wasn’t trying to get anyone to do anything other than think, there was no directive involved.

Second, some of my close friends were school teachers, and were always lamenting the lack of any materials for teachers that were about radical political history. After hours of conversation with my then roommate Liz (who is an elementary school teacher) we hit on the idea of making a poster celebrating Malcolm X’s birthday. She found the Malcolm X quote, “Armed with the knowledge of our past we can charter a course for our future. Only by knowing where we have been can we know where we are and look to where we want to go.” That led to the first poster, and the quote has basically become the motto for the project.

It started with just me making posters, but after the first couple I thought it would be cool to start getting other artists involved, and I also started getting requests from artists asking if they could do posters. And that is how it has continued to grow, and nice combination of me soliciting posters from cool artists I meet, and artists getting in touch with me out of the blue and sending amazing poster mock-ups!

Has CPH lived up to your hopes of what it would achieve? Do you think it’s been aided or hindered by the fact it had large print runs of identical pieces (as opposed to people cutting their own stencils or creating their own paste-ups)?

I’m really happy with the impact of the CPH project. So far there has been 48 different posters by 40 different artists, with a total of over 100,000 posters printed and distributed. That’s a lot of posters about history! Thousands have been pasted up in over a dozen cities, and thousands of others are hanging up in people’s houses and rooms for thousands of other people to see. People can and should cut their own stencils and print their own posters, the more the merrier! But I also think it is important for some art and propaganda to have as far a reach as possible. My hope is that we can change the world for the better, and to do that we need as many people as possible engaged on as many levels as possible. Not everyone is going to wake up in the morning and cut a stencil, but if someone sees a CPH poster on the street it might peek their interest in a point in history, then they look it up at work on wikipedia, and they are beginning to be engaged in the process of challenging the world we inherit, and starting to change it, rather than just accepting it as is.

What are your hopes for the future of CPH?

For the most part I want to just keep producing more posters, by more artists, about more diverse subjects. I’d like to work with more artists outside the US, as well as produce more posters that are bilingual, and can spread further across the globe. At some point soon I think I’d also like to produce a book about the project that chronicles the last ten years, but also includes a bunch of educational materials that can help teachers use the posters in classrooms. Kids definitely need to learn more alternative history, and hopefully the CPH posters can help.

You recently edited Realizing the Impossible: Art Against Authority with Erik Reuland on the history of radical artwork. What led you to write the book?

Both Erik and I were really interested in the intersection of art and anarchism, but the topic has been seriously under-explored. So we decided it would be cool to put together a book of writing and images that would be the book we wished existed on the subject, a book for people just like us who wanted to be more serious about thinking about the connections between culture and radical politics. We also wanted it to be an introduction to the subject, something anyone could pick up and get something out of, that you didn’t have to be a graduate student in high theory to enjoy.

So much interesting intellectual work about art and politics is written in such specific language that is almost only used in higher educational contexts, we wanted to filter some of that out to a more general audience. At the same time we don’t want to dumb down the conversation. When people organize a protest or political action, if they are smart and interested in accomplishing their goals then they spend a lot of time planning, and then also assessing the efficacy of their actions after the fact. I think we need to do the same with art. If we want to claim our art is political, then we need to spend some time thinking about what it actually does, and if there are ways we can make it better, so it can accomplish it’s goals more effectively. The book was intended as a beginning to those conversations.

You mentioned with Erik Reuland about how anarchist ideals have driven much modern artwork. Have you any more ideas of writing about the intersection of anarchy and art?

There’s nothing exactly in the works right now, but I’m interested in continuing down this path in the future. I’m currently working with Dara Greenwald on a large scale exhibition that is a global survey of the art, culture and media of social movements from the 1960s to the present. We’re really focusing in on the culture that is produced by attempts at direct democracy, and this, of course, has an immense overlap with anarchism, whether the people involved called themselves Anarchists or not.

LH: In Realizing the Impossible Clifford Harper says that, “Most anarchists displayed an astoundingly philistine attitude to creative work [in the past 25 years]”. Have you shared similar experiences? Why do you think there’s a tendency within radical culture to want art to serve utilitarian functions?

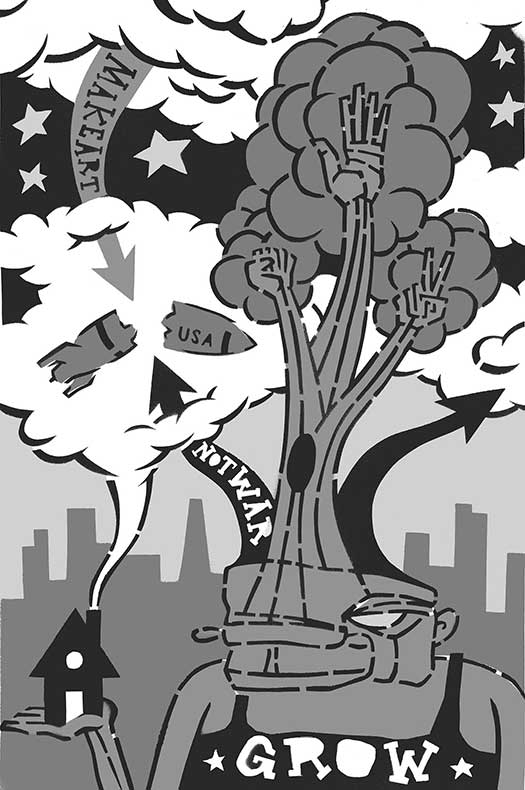

JM: Yes, there is definitely a tension there. In the past I’ve been told by activists and organizers that art isn’t “real” political work, that it is a sideshow to the main event of actual political activity, be it meeting, protesting, union organizing, whatever. You can see this sidelining of culture in the generally horrific aesthetics of most radical political propaganda and activities. Small flyers of white paper covered with lines and lines of tiny black type, endlessly dry looking brochures and pamphlets, boring protests where we stand around and march in circles. Changing the world is going to be hard work, no doubt about it, but there is no good reason I can think of why we can’t do it with a little style! Bright colors, big pictures, creative actions, lets make an activist culture people want to be a part of, not just because it is “the right thing to do,” but because it makes us feel vital and alive.

Josh has recently co-edited a new book, with Favianna Rodriguez, collecting together modern, radical illustrations called Reproduce and Revolt. A review of the book can be found here.