By Justyn Dillingham

You might not know it to look at that small, trim-looking white building next to the School of Art, but inside those walls, universes are colliding.

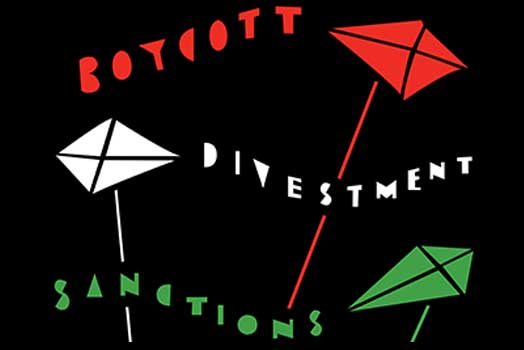

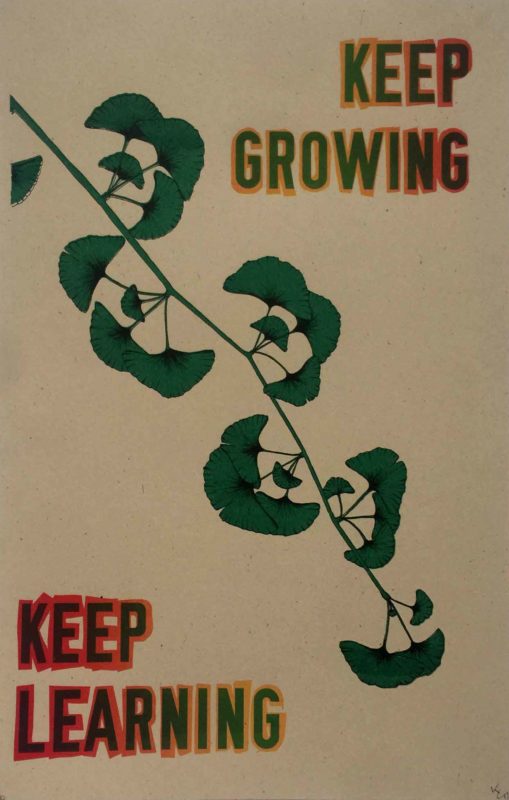

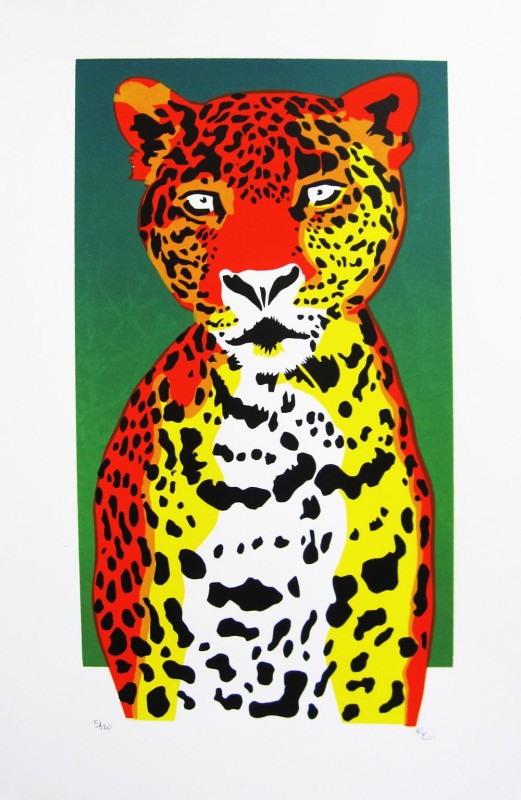

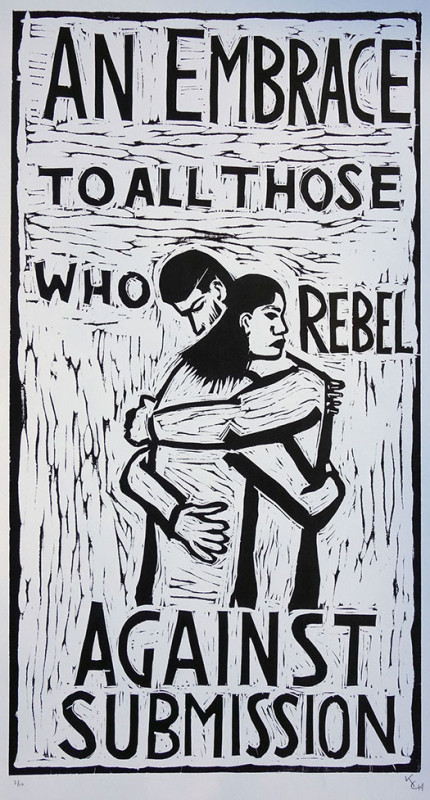

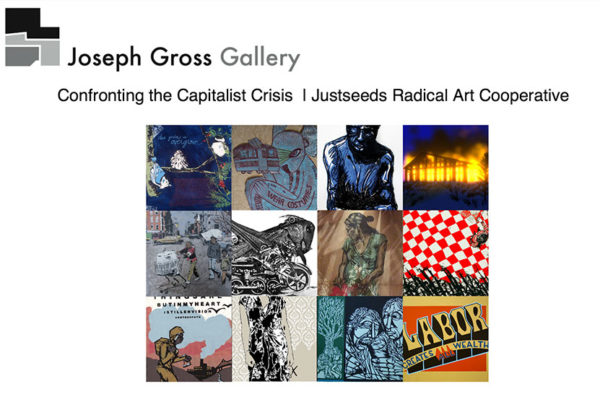

“Confronting the Capitalist Crisis,” on display in the Joseph Gross Gallery through Oct. 7, is a display of prints brought together by the radical artists’ group Justseeds Radical Art Cooperative. It features the work of more than 60 artists from across the country, all illustrating familiar radical themes: the people against capitalism, the people against globalization, the people against “the prison-industrial complex.”

In the next room, the Lionel Rombach Gallery, Chris McGinnis’s “Heritage” is on display until Sept. 9. It’s a startling work: twenty-nine wooden panels spread across the floor (with one on the wall), all painted with eerie, evocative images of industrial America.

In terms of style and intent, these two exhibits are about as far apart as you can get. But their physical closeness is fortuitous. Spend an afternoon walking back and forth between the two rooms, taking in their ferociously detailed images, taking in their messages, and you can begin to imagine the two exhibits having an argument of sorts.

From anger to ambiguity

Slogans scream at you from the walls of the Joseph Gross Gallery: “Solidarity with the Palestinian People,” “How Many Dead Are Too Many,” “Strike While It’s Hot.” Engraved faces, emaciated and stark, glare out at you with despairing eyes — members of the “people’s history” the exhibit celebrates. It’s a striking and haunting compilation of images.

The energy and emotion that went into “Capitalist Crisis” is palpable. If you stand there long enough, you might begin to feel the eerie contrast between the silent noise conjured up by the emotional images and the stillness of the gallery itself.

What “Capitalist Crisis” has not done is find an original way to express its vision. It speaks the familiar language of the Old Left: flags, marches, fists clenched in solidarity. They seem archaic and clichéd because they are. You can almost hear Woody Guthrie strumming his guitar in the background.

Some of the prints are striking — the grim “Hope,” the Soviet-esque “Strike While It’s Hot” — but they’re drowned out by the deafening roar of the rest of the images, all clamoring for your attention. In a way, the visual blare of “Capitalist Crisis” is simply another version of the crass world of mainstream politics; it speaks in absolutes, and if your answers aren’t theirs, there’s no place for you.

The world “Heritage” calls up is ancient, too, but in a more ambiguous way. Some of its panels are flat and smooth, like the ghostly vision of a downtown at night — based on a pinhole photograph McGinnis took of Tucson’s Santa Rita Ballroom, torn down earlier this year. Others are so choked with impasto that they more closely resemble clouds or abstract images than landscapes.

Overhanging the exhibit is a painting of a Ford dealership half-buried under snow. Part of a poem by Vachel Lindsay runs around the room, setting the stage: Kansas, plains, deserted roads. We’re in the America of John Steinbeck, but it’s one that’s been evacuated, leaving behind only landscapes and machines.

“Heritage” is, among other things, a sort of travelogue of America, like “Wichita Vortex Sutra,” Allen Ginsberg’s epic 1966 poem. Ginsberg composed his poem by speaking it into a tape recorder during a car ride through Kansas — which is also where “Heritage” seems to take place, its Tucson ballrooms and abstract snowstorms notwithstanding.

Walking away from the galleries, I felt I understood only too well what the artists behind “Capitalist Crisis” had been telling me; every image practically contained its own footnote. But what was “Heritage” trying to say? Was it condemning industrialism, celebrating it, or simply portraying it?

Recreating the industrial past

McGinnis, a third-year graduate pursuing his MFA in painting, told me he originally planned to display the panels individually on the gallery walls before deciding on the experimental and strangely apt U-shape it has been arranged in.

With its red obelisk — a homemade work made out of wood and painted with automobile paint — as a kind of focal point, the exhibit resembles a sort of mysterious machine. An ideal vehicle, perhaps, for reflecting on the impact of the machine — particularly the car — and its arrival in our society.

The obelisk, McGinnis said, was inspired by the Washington Monument, with all its associations of nationalism and the past, manifest destiny and masculinity, integrity and weakness. “It looks like it’s sturdy but it’s just stacked wood, it’s cheap — it presents itself as something more than it is.”

“I don’t consider myself a political artist,” McGinnis said. “I consider myself a historical artist who attempts to recreate history in an accurate way.”

He said he doesn’t consider “Heritage” a political critique so much as an attempt to evoke the past, with all its flaws and wonders.

“This is our history — good, bad or indifferent. We should critique it, we should celebrate it, but more than anything we should talk about it.”

“Heritage” and “Confronting the Capitalist Crisis” are both attempts to talk about history. While they speak a very different language, it’s heartening to know that there’s enough room for both visions — one angry and direct, the other dreamy and unsettled — in one museum.