Here’s a new review of Realizing the Impossible from the UK anarchist mag Direct Action #41:

Reviews: Realizing the Impossible: Art against Authority

by Josh MacPhee and Erik Reuland

AK Press 2007 – 319 pages – £16.00 – ISBN: 9781904859321

This monochrome book arrived shortly after an interview with Banksy, the “graffiti artist”, had been aired on the BBC. A commentator went along to a working men’s (sic) club in Bethnal Green to view Banksy’s diversion of yellow road markings across the pavement and up the wall to blossom into a flower. Banksy says in the book, “Imagine a city where graffiti wasn’t illegal…a city which felt like a living breathing thing which belonged to everybody, not just real estate agents and the barons of big business”. The club secretary was quite pleased to leave it there. But not all graffiti is of artistic merit and many regard it as degrading the environment. Do graffitos adorn their own dwellings thus?

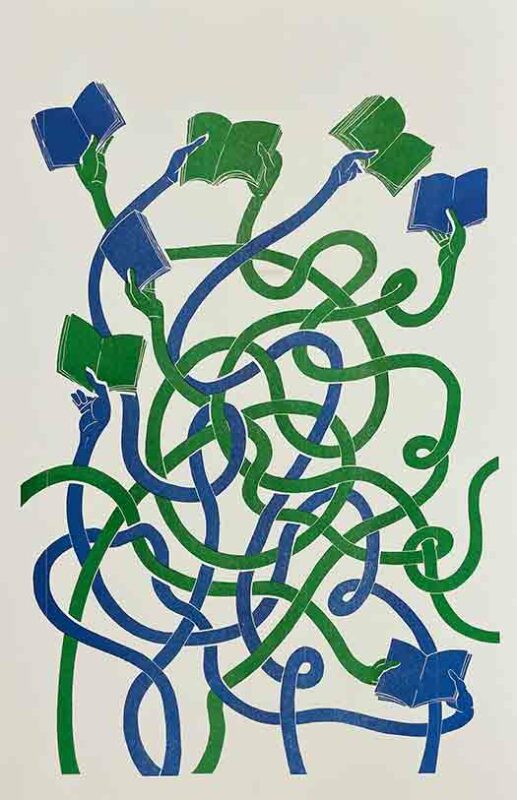

This is not one of those large-format books designed to grace middle-class shelves but is firmly entrenched in anti-authoritarian activism “towards

anarchist art theories”. Whether we need anarchist art theories is a moot point. “Just do it,” perhaps.

The work is wide-ranging: Picasso and Cubism, the forgotten women of Dadaism;

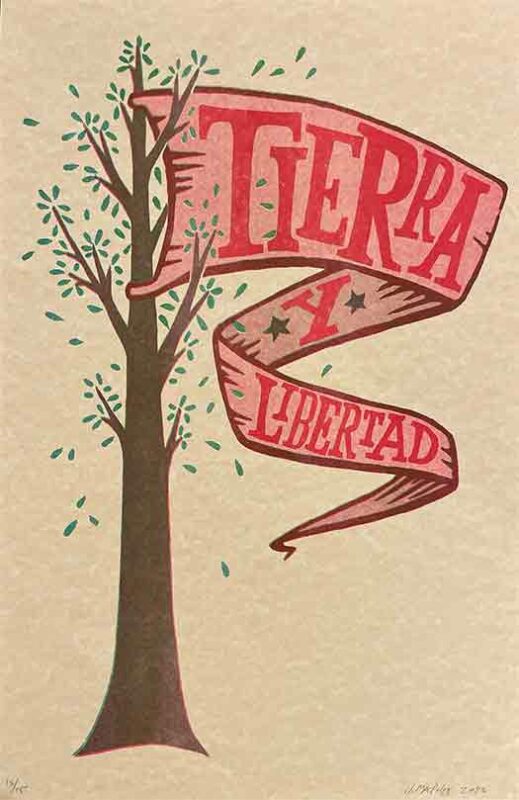

Christiania in Copenhagen; the use of discarded x-ray film to create stencils for spray-painting slogans by Argentinean activists; Crass album covers; Zapatista “Insurgent Radio” and street puppetry; YouTube; video and more. The illustrations vary in quality and the lack of colour lessens the impact of some. Obviously colour would have pushed the price through the roof. There is more text than illustration with lengthy essays that require attention, some being more academic.

As you would expect in such a work, ideas on the conventional art system and galleries vary. Luis Jacob, a Peruvian born artist living in Canada, manages to work within it, claiming that “at some level it is the gallery that must adapt itself to what I do as an artist”. Meanwhile Clifford Harper (“I don’t regard myself as an artist, by the way, I am a craftsman”) fulminates: “The whole thing – artists, art works, art theorists, art critics, art galleries, art schools, art money, the whole dismal thing is so compromised, so hopelessly fucking with the state – fame, greed, wealth, prestige – that it’s best left to its own degradation.”

Artists need to make a living in this capitalist system and in this they, like us, are compromised. As Marianna Cortéz, the partner of Carlos Koyuikatl Cortéz, interjected when he was asked how he would advise anyone struggling to support themselves through art, “You need to have someone else working for you!”

Rudolf Rocker said, when writing of Rembrandt, “The artist became a rebel against his time and drew with keen clarity the boundary between his art and the national Philistinism of his land (Nationalism and Culture p.502). The artists in this work are rebels against the manipulating Philistines of our time. In the final essay Cindy Milstein writes, “The creative act – the arduous task of seeing something other than the space of capitalism, statism, the gender binary, racism, and other rooms without a view – is the hope we can offer to the world.”

This book is useful, not to encourage copycat actions, but to foster the imagination. There is inspirational work here aplenty and this review cannot encompass its breadth. A good buy.