Louis E.V. Nevaer & Elaine Sendyk

Protest Graffiti Mexico: Oaxaca

Mark Batty Publishers, 2009

As far as I know, this is the first book out that exclusively focuses on the political street art produced during the uprising in Oaxaca in 2006. Normally one might ask why we should embrace a book on the graffiti of a political rebellion when we barely have any books that deal with the actions of the period or the politics behind them. But as our world becomes more and more media saturated, how people that reject the status quo represent themselves publicly becomes increasingly important. If most people in the US saw anything about the Oaxaca rebellion, it was likely photos of the graffiti it produced on yahoo news. The popular and mass occupation of Oaxaca City lasted longer than the Paris Commune, and all we got were a couple lousy internet slideshows?!?

Thankfully Nevaer and Sendyk give us a much more in-depth look at the streets of Oaxaca than any web news outlet. Sendyk took the bulk of the photos included (over 150), and Nevaer narrates our trip through the images. Unlike most graffiti books coming out these days, this one actually attempts to provide context for the images included. The book begins with a reprinting of an Open Letter in Support of the People of Oaxaca, signed by an international collection of Left public intellectuals, and leads right into a chronology of events in Oaxaca. Nevaer tries to give us the information we need to understand the images, including a history of the PRI Party in Mexico, context for teachers strikes in Oaxaca, background on the Mexican Revolution, as well as the development of the strike in 2006, the formation of the Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (APPO), and the role of women in the struggle. The information provided is generally solid, if a little to liberal and repetitive for my taste.

What unfortunately is missing is background on the art itself. There is no history of the forms used (block prints which owe a huge debt to the Taller Gráfica de Popular, stencils that are a product of the last 5 years of international online image and info swapping by street artists), and we are told little about the artists themselves. Ana Santos is trumpeted as one of the most important artists to develop out of the struggle, the original female stencil artist, but we only get one paragraph about her. Likewise for the collective Arte Jaguar, whose images are compelling but we learn almost nothing about them or their motivations, other than that they seem to draw equal inspiration from the Zapatistas and Banksy. More troubling is the very limited description of ASARO (Asamblea de Artistas, Revolucionaros de Oaxaca). ASARO has been heralded, celebrated, dismissed and railed against by all different factions in the struggle and support networks. Their bold and powerful blockprints (which are oddly missing, for the most part, from this book) have become symbolic representations of the uprising, with international exhibitions being mounted and print sales supposedly going to support the struggle. At the same time some ASARO members affiliations with various sectarian political parties and their behavior as the police suppressed the revolt have caused splits in the movement, with public distancing from some sectors of APPO. When artists are representing a movement, it becomes important to know who they are and what ends they are working towards.

Unfortunately this book gives us little background on the artists themselves, we only get very select quotes from them, and no extended look at their real role in the Oaxacan movement. This is the book’s weakest point, and in-depth interviews with some of the artists could have pushed it from being a really good survey and collection to a great book. I would have liked to have seen a more inside view. To give an example, the image on the cover is by Colombian street art collective Excusado, in town for an exhibition, not to participate in the rebellion. Excusado is not the only non-Oaxacan art we see, the book also captures pieces by Swoon, Seth Tobocman, Bansky and Clifford Harper. The problem is not that these images are included, or that they did not also influence the visual landscape, but that none of the them are attributed in the book, and we are given no context or understanding of why they would show up in Oaxaca at this time. Images by popular street artists are being pulled down from the internet and reproduced in the heat of a full scale rebellion, this seems quite remarkable to me! People call the Zapatista uprising of 1994 the first post-modern revolution, but Oaxaca might be the first post-modern street art rebellion. All of the tools used by art rebels throughout history are mixed and matched in Oaxaca. We see classic relief printing, silkscreened posters, photocopy art, simple street stencils a la the Nicaraguan Revolution of 1979, more high-tech and accomplished stencils created with Photoshop and Illustrator, international images beamed across the internet, flyers using mock-popular culture references, and newspaper editorial cartoons painted directly on the wall. You don’t get much more of an interesting brew of street images than this!

That said, the pictures are the heart of the book, and they rescue it. A really sweeping and broad collection images, Protest Graffiti Mexico not only captures the spray painted scrawl and stencils, but a full range of public expression. Their are almost two dozen images of protest banners, as well as flyers, posters, and hand-painted characters. We really get a feeling of what the streets looked like at the time, with every wall covered with multiple layers of messaging, stencils having to share space with wheat pastes and scrawled cartoons. The diversity of images of hated Oaxaca Governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz (URO) are impressive by themselves, with hundreds of Oaxacans spilling their hatred and unique visual representations of URO. Even with it’s limitations, this book is a must-have for those interested in the Oaxacan struggle, or political street art more generally.

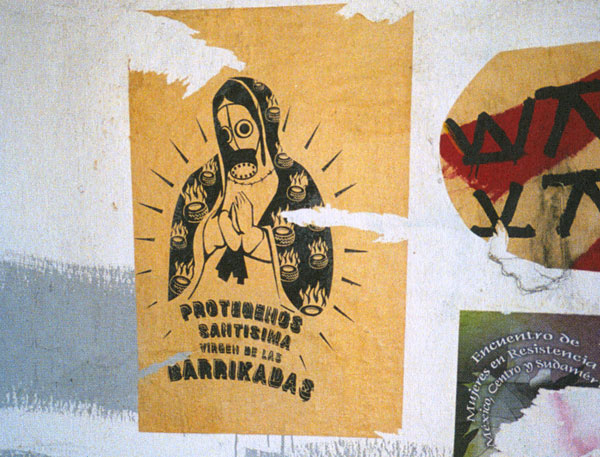

(one of my favorite images from Oaxaca: “Protect Us Most Holly Virgin of the Barricades”)

Thanks Josh!! Just ordered this. I haven’t seen it. Do you know either of the authors?

I believe Sendyk was a photographer who happened to be in the right place at the right time. Nevaer is a journalist I think, I don’t remember there being a proper bio in the book. He seems to be one of the go-to guys for Mark Batty Publishers when they have a collection of images and need to provide context, esp. youth culture/latino related. He also edited the Illustrations from the Inside book I reviewed a month or so back.

I have lived in Oaxaca for the past ten years and Elaine Sendyk and I were good friends. She died unexpectedly almost two years ago. The amazing fact concerning her photos is that she was not a photographer. These photos – each and every one of them – were taken with a throw-away camera. Professional photographers who reviewed her work always assumed she had used a state of the art camera. She had the most extraordinary eye and as the rebellion in Oaxaca took hold and developed, she became emotionally involved in the efforts of the teachers and APPO and, particularly, with its artistic representation. She walked the streets of Oaxaca searching out every bit of graffiti she could find. The fact that this book exists is due largely to the efforts of her sister, Ellyne, who was determined to see these photos published as a tribute to Elaine.

Interesting! There is nothing in the book to imply she wasn’t a photographer, and also nothing that explains why she ended up in Oaxaca. Based on what is in the book, I assumed she was a socially-conscious photographer who happened to be in Oaxaca when the strike broke out, and did what she could to help.

I agree with Josh’s points above.

Providing more depth about the producers of the street work could have pushed this book even further as a document of social struggle and culture production.

Giving the trajectory in Mexican society that led to the rebellion is crucial, yet its surprising that the incredible history of Mexican printmaking and image production is not mentioned. Even though there weren’t direct references of many influential Mexican artists, like Jose Guadalupe Posada, Leopoldo Méndez, Alberto Beltrán, or so many others, in the street based work, was it a conscious decision to leave that history out?

There could be another essay about why certain images and metaphors are utilized, with acknowledgment to the mediums from where they were taken. The internet, television, etc.

Visual and “popular” mass production is very unique to Mexican struggles. The approach of communicating political concepts and social history in simple graphics then mass-produced as leaflets, pamphlets, and posters, or painted as murals is invaluable. It is necessary to connect that history to the production in these recent struggles.

I met Elaine when Visual Resistance was installing the ASAR-O exhibit at ABC no Rio, in NYC, a few years ago. She was kind enough to leave a portfolio of her documentation in the gallery. It was really helpful to have those images to contextualize the prints and stencils that adorned the walls.

I did find it “funny” that a paper cut-out that I had wheatpasted with Swoon was included in her binder, and later the book. Elaine was surprised when I explained who’s work it was and that it was installed before the uprising.

It occurs to me that she was documenting everything she encountered, now for our historical benefit, yet when some are placed together in this book, without specific context, or attribution, they can be confusing.

In looking for images I found a short piece of writing, about Oaxacan graffiti, accompanied with some photos:

http://www.wanderoo.net/oaxaca_resiste/street-art.html

Interesting review. I’ve spent some time with ASARO artist collective in Oaxaca. They are a fascinating and diverse group, from devoutly religious to devoutly Stalinist. I’ve written a number of essays on them for an online magazine, Commonsense2.com

Most of the ASARO essays are linked to this story:

http://commonsense2.com/2009/03/politics-world/oaxaca-update/

Best,

Kevin McCloskey

I could not agree more with your criticisms, the frustration at lack of background on stylistic aspects of the art. Even something on the location of the pieces. And something on Che. It drove me to Google, of course, and your review, and also to wonder why Banksy is also Bansky, or which is which? And yes, the whole story and history is more nuanced than the simplistic account given. I found the book for sale at the Oakland Museum of California in conjunction with a show on African influences in Mexico. I’m glad I found it. And Oaxaca, what a great place, I was there last November! Anyway, thanks for your review.

I did a Yahoo search on Elaine Sendyk and found the website for mesoamerica foundation. Elaine was my first cousin and we lost touch over 15 years ago.

I did not know she was living in Mexico and I was truly upset to read that she had died.

She did not have a sister named Ellyne or any sisters. She was the only child of my Mother’s sister Hilda.

I would like to be in touch with anyone who knew her during her years in Mexico and I would like to know where she is buried and what happened to her African collection of art and handmade Jewelry. It should be displayed in a Museum for people to see. She made many journeys to Africa and I loved to see the artifacts she brought back and hear her stories.

Any information on Cookie’s last years on Earth would be welcomed. I tried to find her about 8 years ago and the search came up with nothing.

In response to Annette’s comments….Elaine and I also lost track of each other when I moved to Massachusetts and I too was terribly saddened to learn of her death while googling recently as I had never forgotten the Cookie who graduated HS with me in 1954. That was Washington Irving HS in Manhattan. We each lived in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn and rode the same subway uptown to 14th St every morning for three years, becoming fast friends. We even once double dated identical twins. She was a beautiful young girl and a gifted artist and our HS offered choices to foster our creative sides. I was thrilled to find a photo of her online and the sculpted face was the same as I clearly remembered. I never knew anyone else who could throw an ordinary scarf around her head quite like she did and pin it to one side and look totally glam…though I tried and tried! It pleases me no end to know that she continued to express herself and her ideas and communicate them through her creativity. It appears she pursued her dreams and enjoyed her life. I’ve ordered a copy of the book with her photographs. I don’t care what kind of camera she used to take her pictures, their value lies in the intuitive eye that pursued, observed and captured them for posterity and that was all about Elaine!

I was thinking of Elaine (“Cookie” to her friends and family at one time)today and began a Google search for her for the first time since I lost contact with her at least 7 years ago. I was pleased to read Suzanne’s and Barabar’s posts which revealed to me that this was the Cookie I knew from girlhood in the Catskill Mountains and in Brooklyn before and a after her mother died. And, of course, I was saddened by the news of her death; I thought, today that on a future trip to NY I would contact her. I remember her fondly (as will members of my family and some friends)and the lovely jewelry and ceramic sculptures she created, some of which were presented to me as a gift and which I still have. Her association with Ornette Coleman led her to Africa where she collected African instruments for him.

I would love to hear from both Suzanne and Barbara on this blog to begin with.

Unfortunately there is terrible news from the state of Mexico where Elaine was photo-documenting.

http://justseeds.org/blog/2010/04/armed_attack_on_the_support_an.html