To purchase a copy, you can click HERE.

To check out the website for this project, click HERE.

Issues of feminism and gender equality are not situated in my life as a single critical mass that can be excavated in one dig. I went to college, worked in industry, got pregnant, decided that day care was awful when my kids were young and elected to stay home until they started school, embarked on a master’s degree and new career when they were old enough and then plunged into the world of working and raising kids with all of the joy and frustrations that come with a woman’s dual career. In addition, I had a child with special needs at a time when her need was not readily diagnosed. My feminist experiences are buried within work and the mundane and in quiet experiences that undulate but don’t erupt. I was not an activist; I was a crusader in the worlds I inhabited: a corporation where I fought to have the rights of female clerical workers recognized; a neighborhood where I was a good friend and ally to a woman in a claustrophobic/dictatorial relationship; schools where I heard the weakest voices as clearly as the strongest; my own home where being a mother to my daughter has always been a loving, confusing dance with both of us leading and both of us following.

I learned about sex and my body from three sources: home, a progressive Reformed Synagogue, and on the street. My mother was a nurse. Somehow I think that helped her understand that it was natural for a child to learn about her body in a way that was age-appropriate and gentle. Or perhaps it was my understanding of her profession that gave me confidence in her; I am not certain. Although I cannot recall when the subject first came up, I know that when I was in seventh grade and already menstruating, I felt relatively comfortable talking to her—if indirectly at times—about sex. Once it was with a group of my girlfriends from school. We sat around the kitchen table complaining about our periods and broaching the subject of boys. We were certain that they must have a comparable monthly experience to move them toward their sexual maturity. We pressed my mother, believing there was some secret she was keeping. She did not budge on the “the boys’ menstrual cycle” but in the process of assuaging our sense that nature was decidedly unfair, she spoke of basic sexual matters and couched them in terms that made our present and future sexuality seem like something good.

In the early and mid-1960s I spent about five years in religious classes at a well-known Reformed Synagogue in the Philadelphia suburbs. Looking back as both parent and teacher, I realize now just how extraordinary an experience it was. The entire religious community was very liberal and intellectual. I did not appreciate at the time that among my teachers were leaders in the community, judges in the courts, and intellectuals from universities. We had classes in everything—ethics, comparative religion, and sex. The sex class was a one day, intimate experience with two superb rabbis; one was a distinguished historian and writer, the other his young protégé, who would go on to be a noted progressive rabbi who defied tradition and ministered to interfaith couples. They spoke to us candidly and tried to help us see sex as something natural and something we had to handle with self-awareness and respect. They opened the session to questions at the end of the presentation and no question was off-limits. The most outspoken of us raised her hand and asked, “How does it feel?” The room was silent; she echoed what each of us wanted to know most. The rabbis did not know what to say at first, but somehow they let us know that it was an appropriate question within all of us and one they had no real way of answering. We would find this out on our own.

Sex education on the streets came earlier, in the late 1950s. Before we moved to the suburbs, my family lived in an integrated, working class neighborhood in the city. We had very little money since my divorced mother, who would later remarry, was struggling to keep me and my older brother afloat with her nursing job and no assistance from my biological father. We had a rented row house in a pleasant neighborhood. In the summer my older brother and I walked about a mile to a public park that had a summer program for kids. In the walks home with kids who ranged in age from about six years like me to early teens, I was privy to sexual innuendo that I did not understand but that did not frighten me. One day, however, I was playing with some other kids about my age in the alley behind our house. I did not really know them; we just took up with each other that day. They were wilder than I was and I felt myself an outsider. I continued playing with them, however, because I was hungry for friendship. At some point they wanted to go the basement of one of the houses and I followed. There, a boy and a girl took off their clothes, got on a table with the boy on top of the girl and started rubbing their bodies together and making sounds. The two other onlookers were laughing and shouting in ways that made it clear that this was something taboo. They all seemed familiar with the raw intimacy that I didn’t understand. I just stared for a minute or so, felt things in myself that I had never felt before, and I left in fear, without saying a word. I ran home and told my grandmother, who lived with us. I recall little of the conversation we had, but I know she tried to explain it to me as well as she could. What I do know was that those kids were trying things that I had never seen before and the spectacle they put on in the basement frightened me. I know that it affected my view of sex in the short term in that what they did made me feel shame. Later I learned that sex should not be associated with either fear or shame, and I resolved that when I had children that I would try to make discussions about sex natural and positive.

I fancied myself an intellectual in the 1960s, but I was also a cheerleader. That dichotomy has been with me all of my life, and in some ways it shaped my emergence into every stage of life. I was sixteen when I worked endless days and weeks to make the cheerleading squad at my high school along with my friend from elementary school, Susan. Those were the days of pom-poms, megaphones, black and white saddle shoes, and twelve girl squads.

Two years later, in 1968 when I was a senior in high school, I missed as many cheerleading practices as I could without being dismissed from the squad, and I subscribed to a magazine called Avanti Guard that was filled with wild and provocative art, sexuality that was raw, and language that I had never seen in print nor, I might add, had ever uttered. It seemed like a key to another world. When my mother found it under my bed she was appalled. (If I had ever kept up the responsibility of cleaning my room she would not have found it!) She called me downstairs to have a very civilized talk: I know that she was frightened for me and did not want to push me away. I told her that this was an art magazine and that I wanted to know more about life beyond the suburbs. I don’t think I was savvy enough to use that expression; I probably intimated it in some teenage way. I might have referred to Sgt. Pepper for dramatic punch.

The issue of shame and sexuality confronted me again when I had my first job after graduating college. I was working for a large engineering firm, and aside from women in clerical or administrative capacities, the hundred or so people I worked with were men. Over time I became friendly with David, who like me was in his mid-twenties. We developed a great friendship, but although I was open about my personal life, David said little about his. At one point David became visibly depressed for quite a few days. I asked what it was about and he hesitated. He said that he feared if he spoke openly, that our friendship would end. I assured him that he could tell me anything and I would not be judgmental. I suspected he might be gay, but I was not certain. He finally swore me to secrecy and confirmed his sexuality. To say that he was overjoyed at my supportive reaction is an understatement; this company was the bastion of button-down manhood. David knew he was an outsider and he feared for both his job and his reputation with his colleagues. This was six years after Stonewall, but the reality was that to be openly gay in a conventional work environment was risky. David felt fear and a shame that was unnaturally imposed upon him.

David was the first gay person I ever knew who wanted me to know about his sexual preferences. Homosexuality was not a topic with which I was very familiar; if alluded to at all when I was a child, it was with code words which I only vaguely understood. I knew no openly gay people in high school and only one or two in college. This is drastically different from today where I have students in my high school English class who are either open about their sexuality or make an effort to let me know individually once they are certain that I can be trusted. Most of the cautious students open up about their identity completely before they graduate. Even so, I know that some still struggle in terrible ways. This past year a student wrote a short memoir for my class and included a note at the end about his sexuality. In the note he said that his family was very religious and that they had him going to a class to “change his attitude” about his sexual identity. He is a bright and talented young man—evidently the best academic achiever in the family. He told me that his father once told him that the family finally had someone who could be a success in life and “look what he turned out to be.” I know this young man will make it; he knows he is gay and he is looking forward to life. It is just so sad that he must deal with such pain while he moves toward it. When I consider the kids I knew in high school who were gay but unable to admit it until later in their lives, I envision the torment they must have felt pretending to us all—and perhaps, themselves.

Growing up, I knew what abortion was and that it was a dangerous, secretive deal. Like homosexuality, the notion of abortion was avoided and inferred rather than discussed openly. My grandmother spoke of it as something awful, something done in dirty places by men who were not doctors. She said she knew a girl when she was young who had an abortion and almost bled to death; the girl was unable to have children after the abortion. That would have been sometime in the 1920s. She also talked about some movie stars alleged to have had abortions, but I don’t recall who they were. I found it strange then and now how news of illegal abortions of famous people reached the public. As I write, I cannot even imagine how we came upon this topic, but I know it made me feel that there was something wrong if when abortion was mentioned, it always seemed as if it was a burden for a woman to bear alone and that it was a choice riddled with shame—again born by the woman. It was alluded to in old movies like Men in White and A Place in the Sun although the word abortion was not mentioned; I barely understood the references. These films, like the hushed conversations, made a woman seem singularly culpable of something unutterable.

I recall very clearly when Roe vs. Wade made abortion legal. I felt it was a victory for woman and made the “back-alley” abortions that my grandmother told me about a thing of the past. But almost the moment Roe was made a law, it also became a money-making scheme and that repulsed me. I recall looking for a job sometime in 1974—there were few opportunities for graduates with a BA in English—and answering an ad that required intelligence and an articulate manner with the public. When I called, I was asked to come for an interview, but I was not told what the job would entail. When I arrived at the address—a private home rather than an office—I became engaged in a conversation about Roe and treated to the excitement of an entrepreneur who was giddy at the prospect of getting in on the bottom of an enterprise where, because of the inevitability of sexual impulse, money could be made indefinitely. My job would be to engage the pregnant women who called and assure them that this was the right choice and the right place. The entrepreneur—a man—would simply contract out the abortion to a doctor on a list. In addition to a salary, I would make a commission on each abortion I “booked” for the business. I left there appalled; here was a law intended to emancipate women from torture and shame, and it was for this man a lucrative career with no regard for the individual. Later in the 1970s I became aware of decent women’s clinics like Margaret Sanger in Philadelphia. A friend of mine volunteered there and related positive accounts of women getting counseling and care from people dedicated to their wellbeing rather than money.

Likewise, around the same time, I remember a couple I met while taking graduate classes. They had the most wonderful way of making conversation with anyone and they seemed almost self-mesmerized by the notion of rallying God’s minions against abortion. They had a messianic way of speaking that both amazed and repulsed me. They always had pamphlets to hand out and meetings to invite you to. They were my first glimpse into Christian Fundamentalism resolutely directed toward political change, and in the years since, I realize how very naïve I had been to think that everyone in my generation was looking for enlightenment.

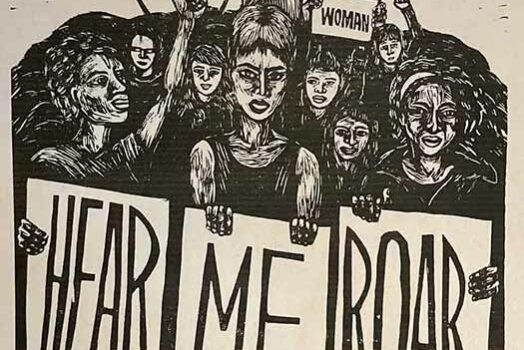

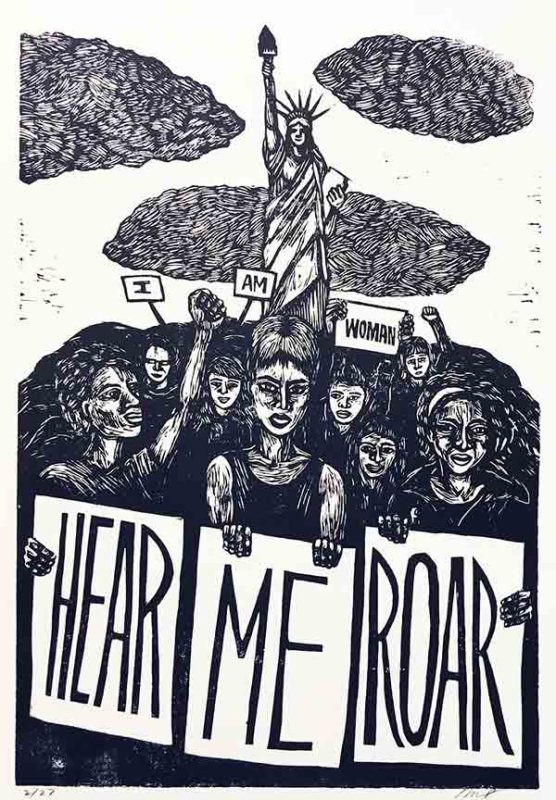

Today I find myself worried by the undercurrent of self-righteous attitudes about reproductive rights in the country. Initiatives in states that seek to not only dictate choice but invade a woman’s body seem culled from medieval times. I believe there is an ages-old hubris that manifests itself as concern for the rights of all but is actually an insidious effort by some to control women and limit freedom to a definition imagined by would-be oligarchs who want a white, Christian nation modeled on a reality that never existed. I believe this is a powerful minority, but one that benefits from apathy in much of the general public. I am so grateful to women and men with the courage to speak out and rage against oppression despite the many masks it wears. But I wish we also had more people interested in public affairs and willing to vote. We need vigilance so that what we have gained is not lost.

-Elizabeth Esris