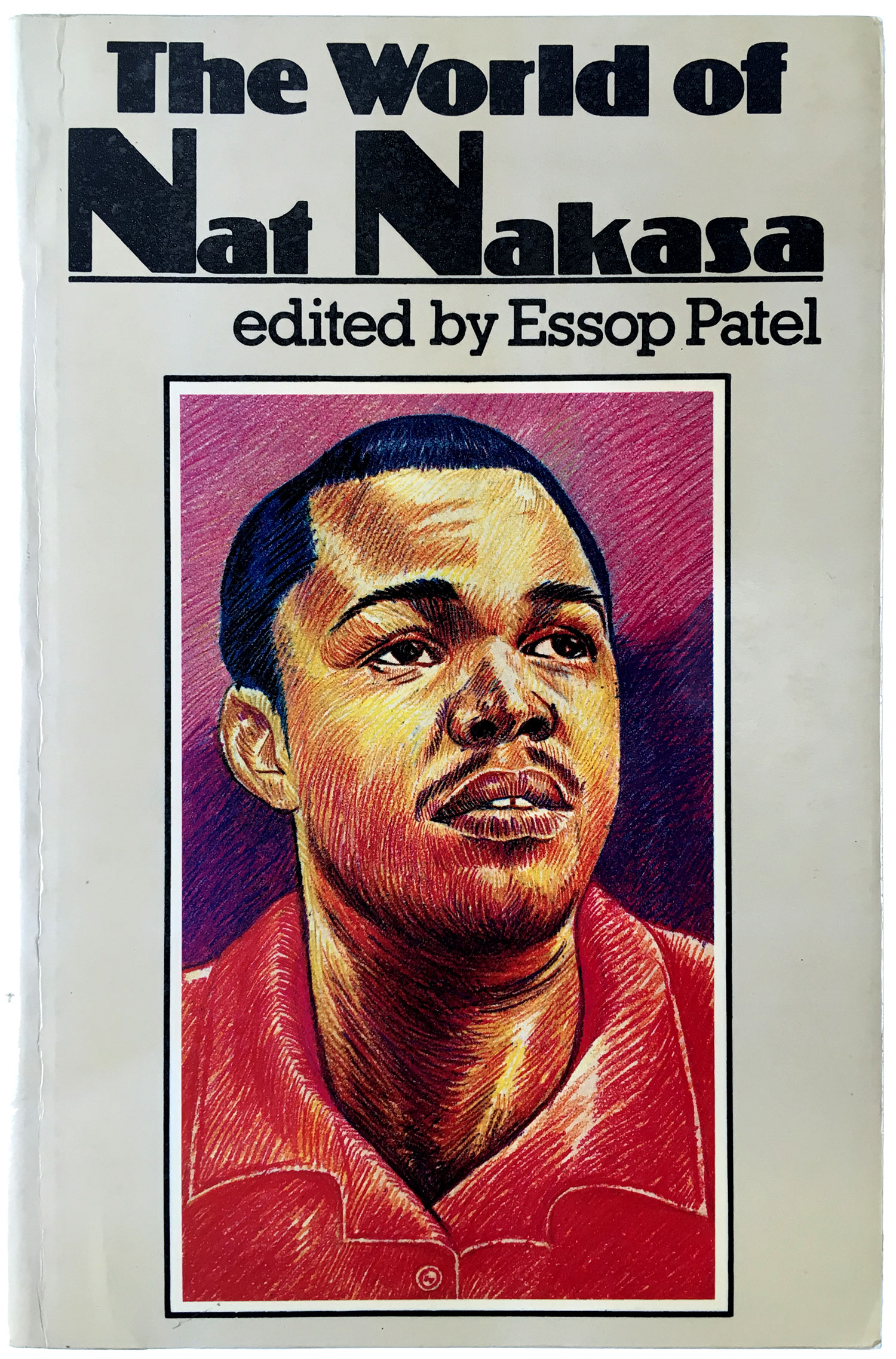

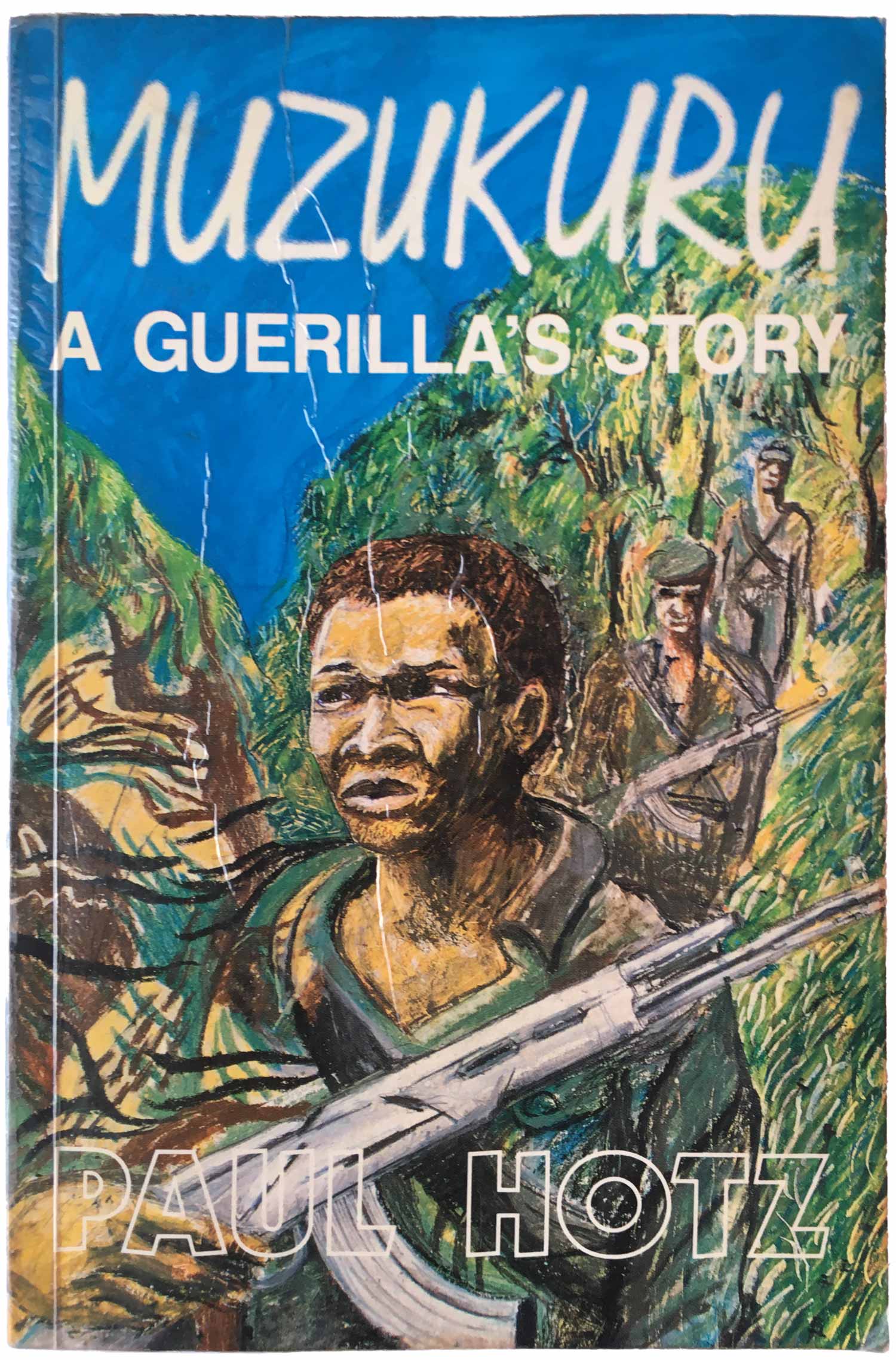

This week’s focus is on the South African published house Ravan Press, which was founded in 1972 by Peter Randall, Danie van Zyl, and Beyers Naudé. On second glance, you’ll notice the name of the press isn’t Raven, and isn’t named after a bird, but instead Ravan Press, the “Ra” from Randall, the “va” from van Zyl, and the “n” from Naudé. Regular readers of my book cover posts here might recognize Randall’s name, as he was the founder of Spro-Cas, an anti-apartheid project and publisher I featured in post 212. Naudé was also a white, Christian anti-apartheid activist, and I believe Danie van Zyl was as well. Randall and Naudé were banned multiple times by the South African government (an interested S. African invention, the banning of a person in their own country—which functionally meant a unique version of house arrest and a prohibition on all publishing by that person). The founders wanted to really push the limits of the protection whiteness gave them under the apartheid regime, and Ravan quickly became a who’s who of South African literary figures, publishing the full range from classic “struggle” literature by Sipho Sepamla (or the guerrilla narrative above, Muzukuru) to putting out the first novel by J.M. Coetzee, Dusklands. Much of their early output was banned by the government.

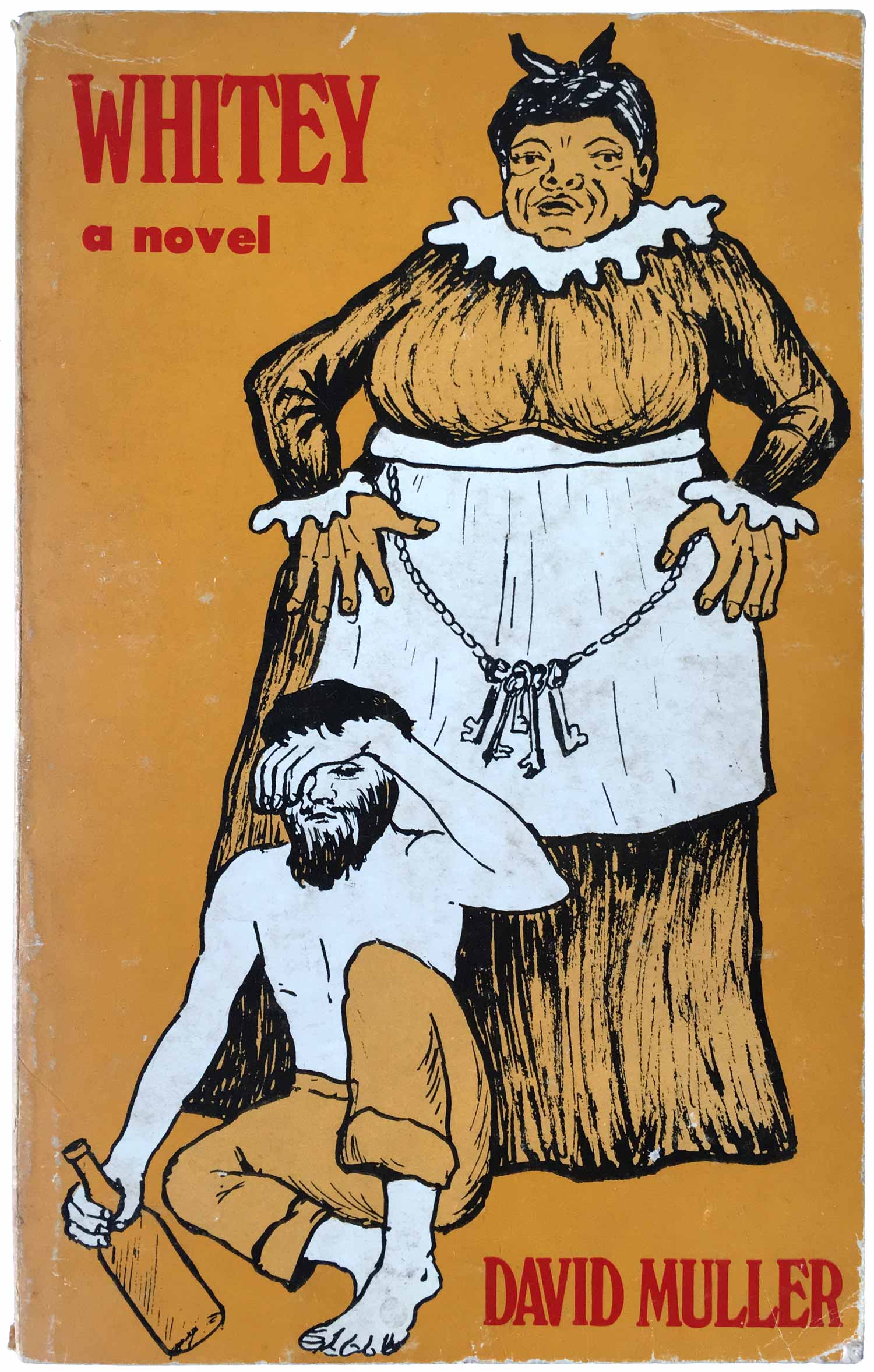

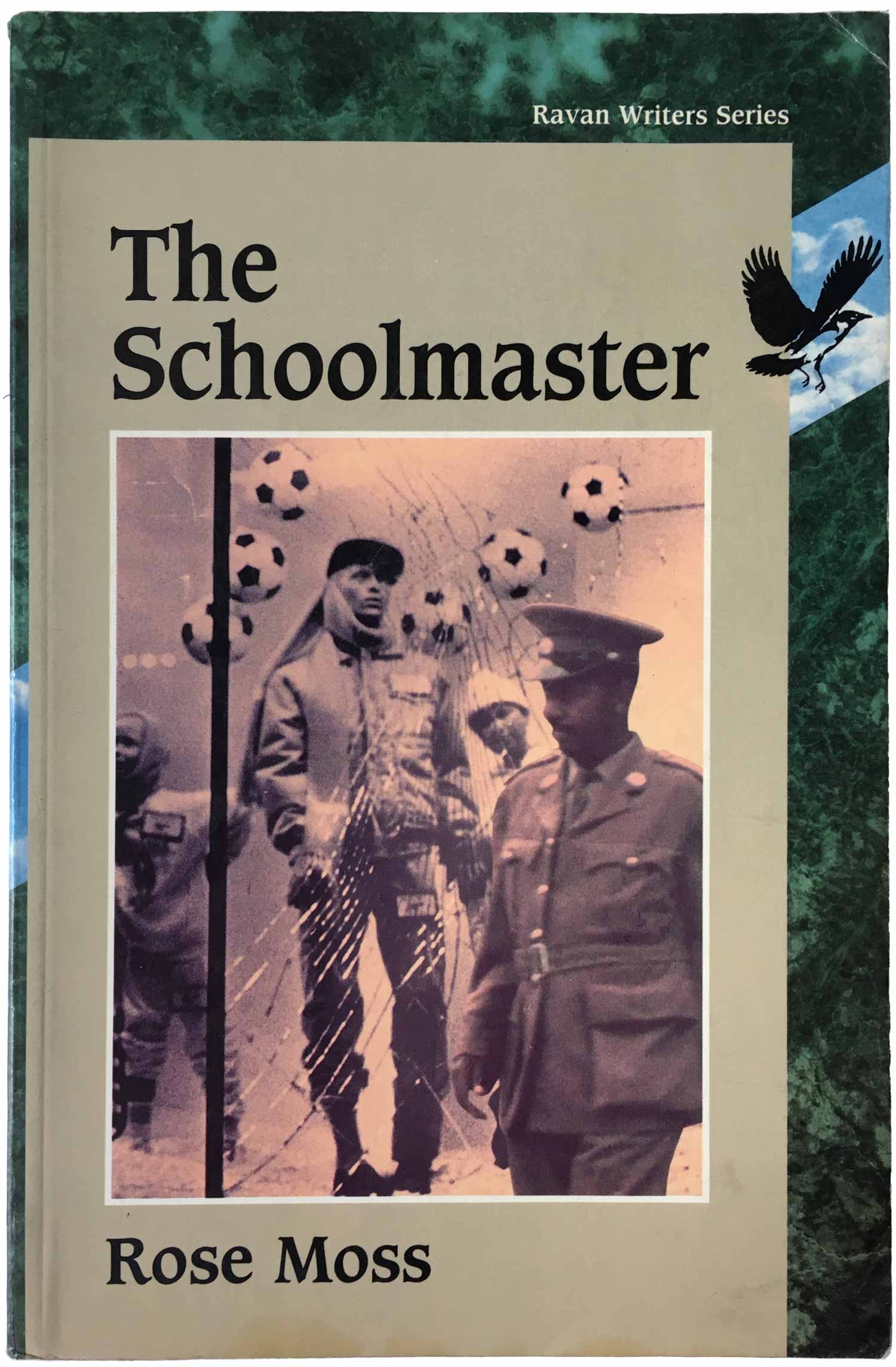

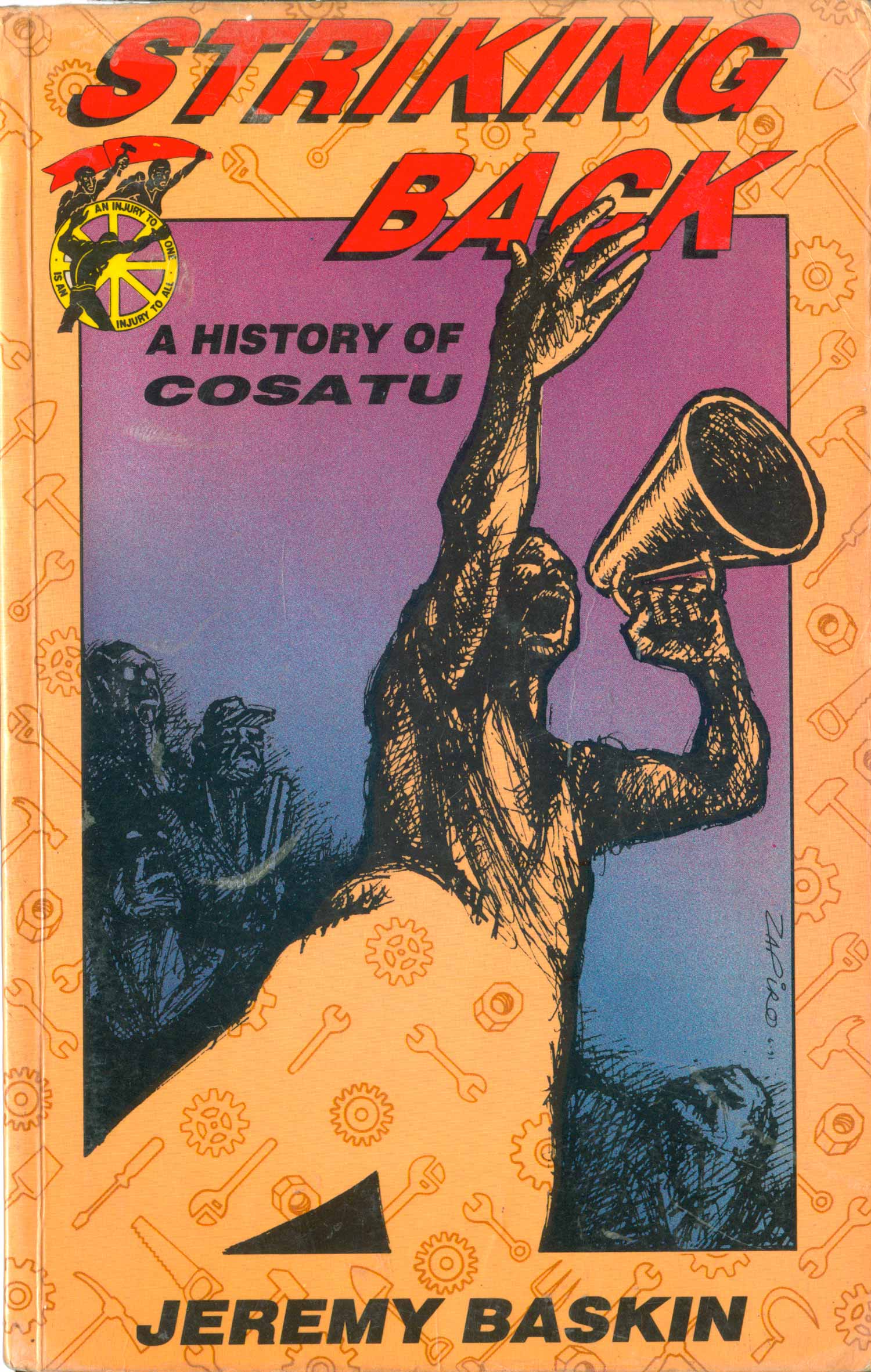

The core of the Ravan list was fiction, which included a both a random assortment of novels, but later series of books, including the “Ravan Writers Series.” Most—if not all—were South African, and a very strong mix of all the different racial groups in the country, from Afrikaaners to English whites, Indian and “Colored,” as well as titles from multiple Black African ethnic groups and languages. Below are a couple of these novels, as well as a history of the biggest labor union, COSATU. The COSATU cover features an illustration by Zapiro, or Jonathan Shapiro, one of the country’s most popular editorial cartoonists who had been a militant against apartheid.

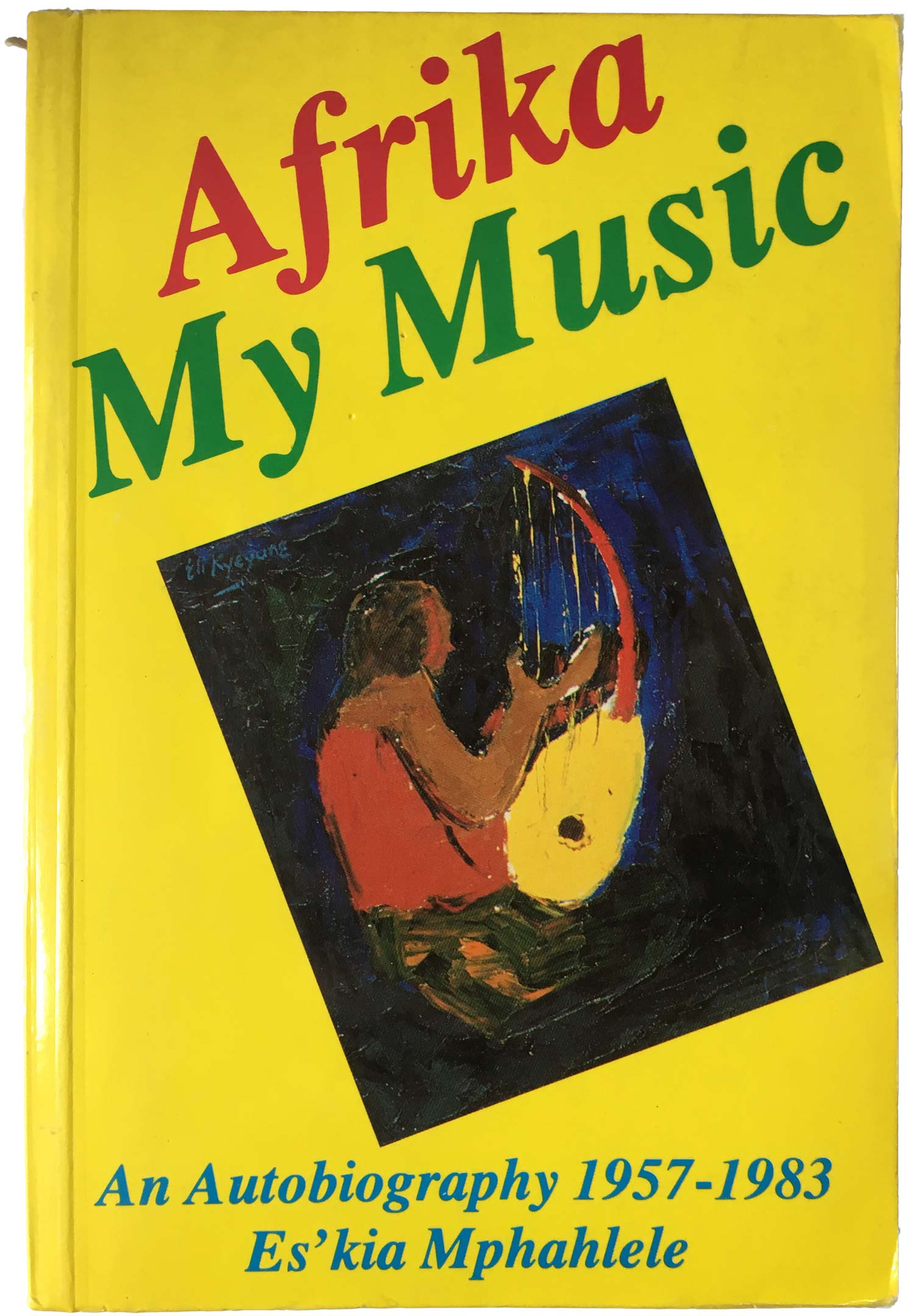

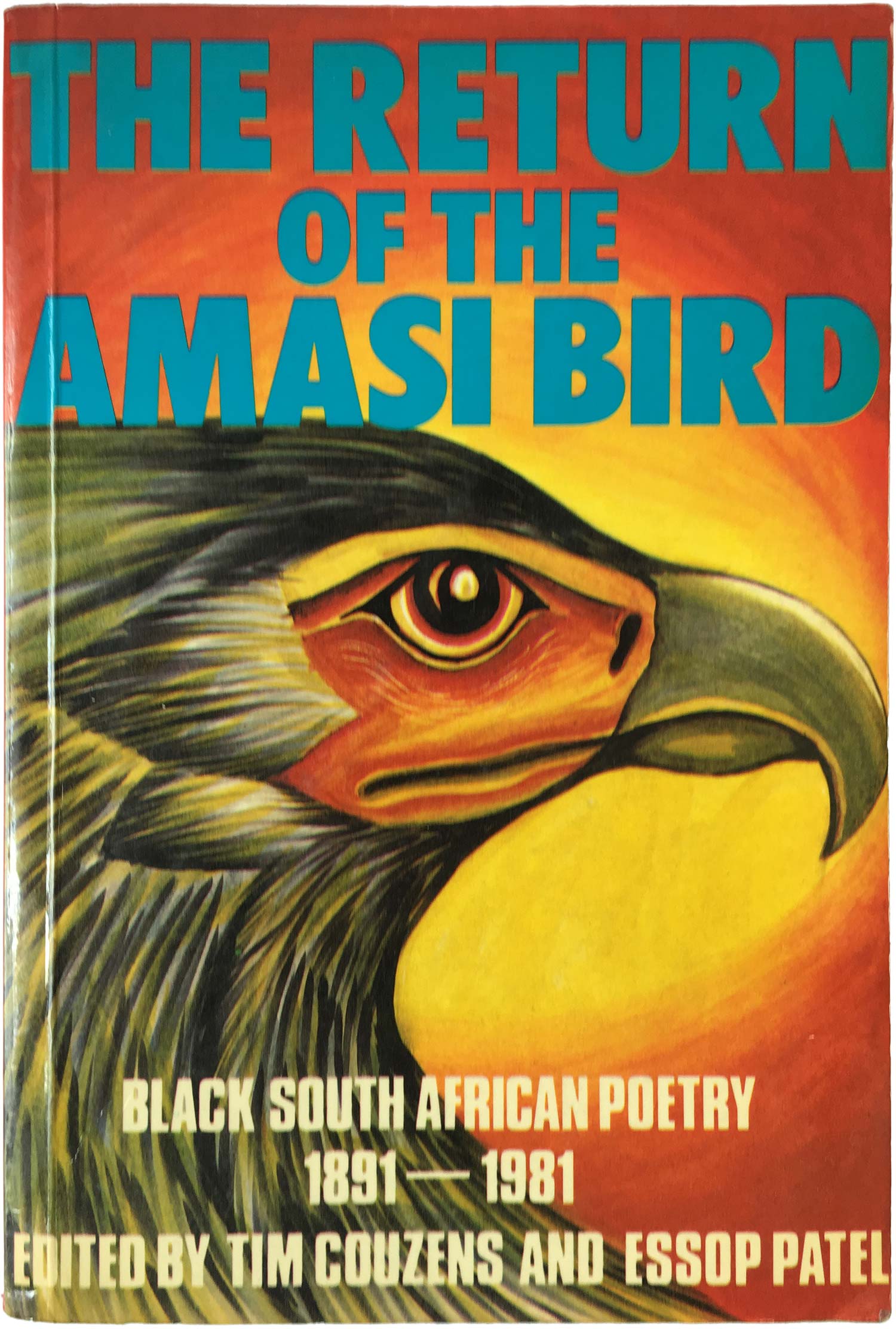

Here are two more titles that seem representative of Ravan’s output: a memoir by one of S. Africa’s most well-respected writers, Es’kia Mphahlele, and a broad and sweeping collection of Black S. African poetry. Both covers feature artwork by S. Africans, and while the painting on Afrika, My Music fails as a cover illustration (or maybe the design fails the painting), the illustration on The Return of the Amasi Bird is both striking and powerful. The blue sans serif title compliments the image perfectly, pulling out the cool colors within the feathers, and boldy giving us the title without diminishing the image.

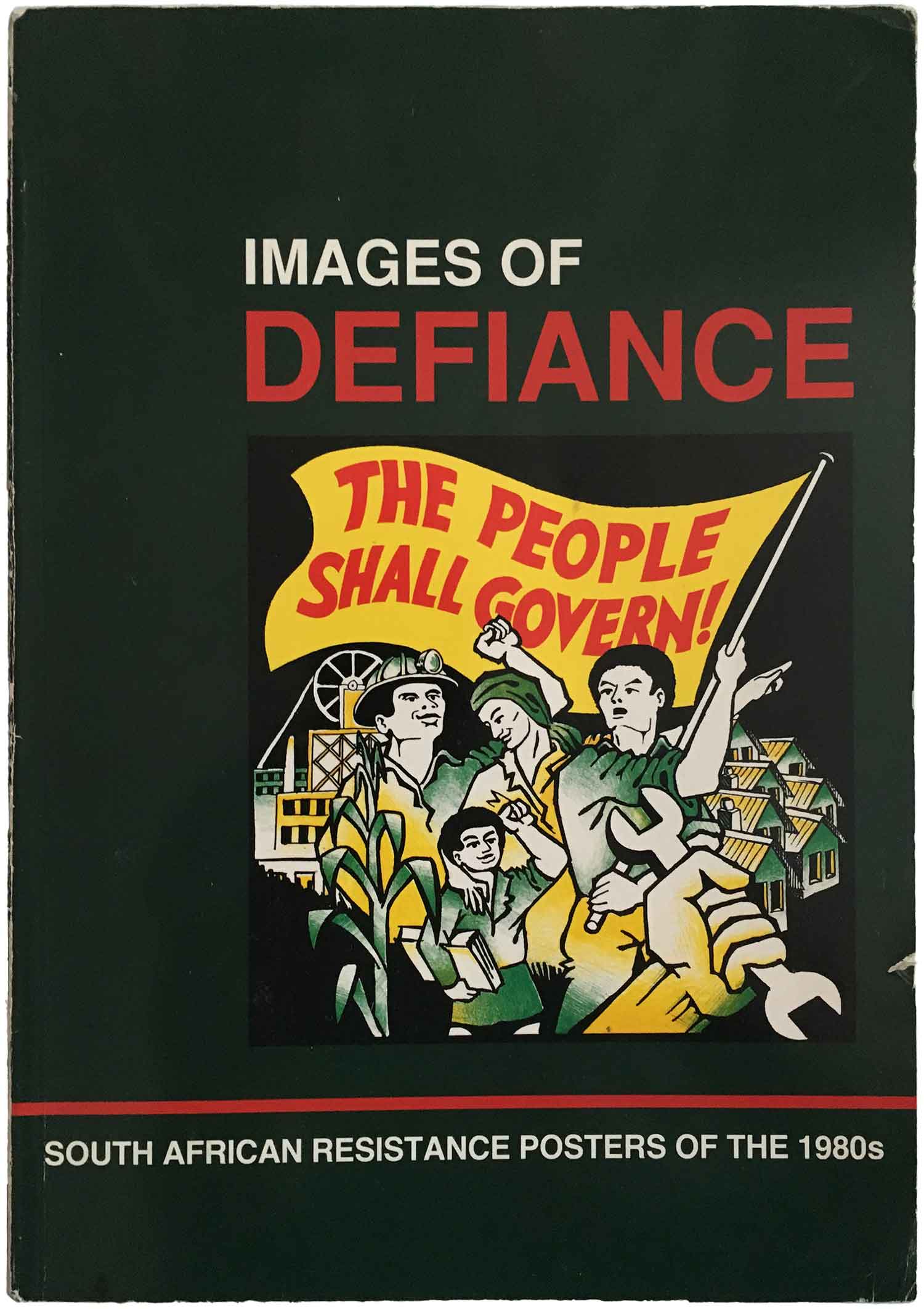

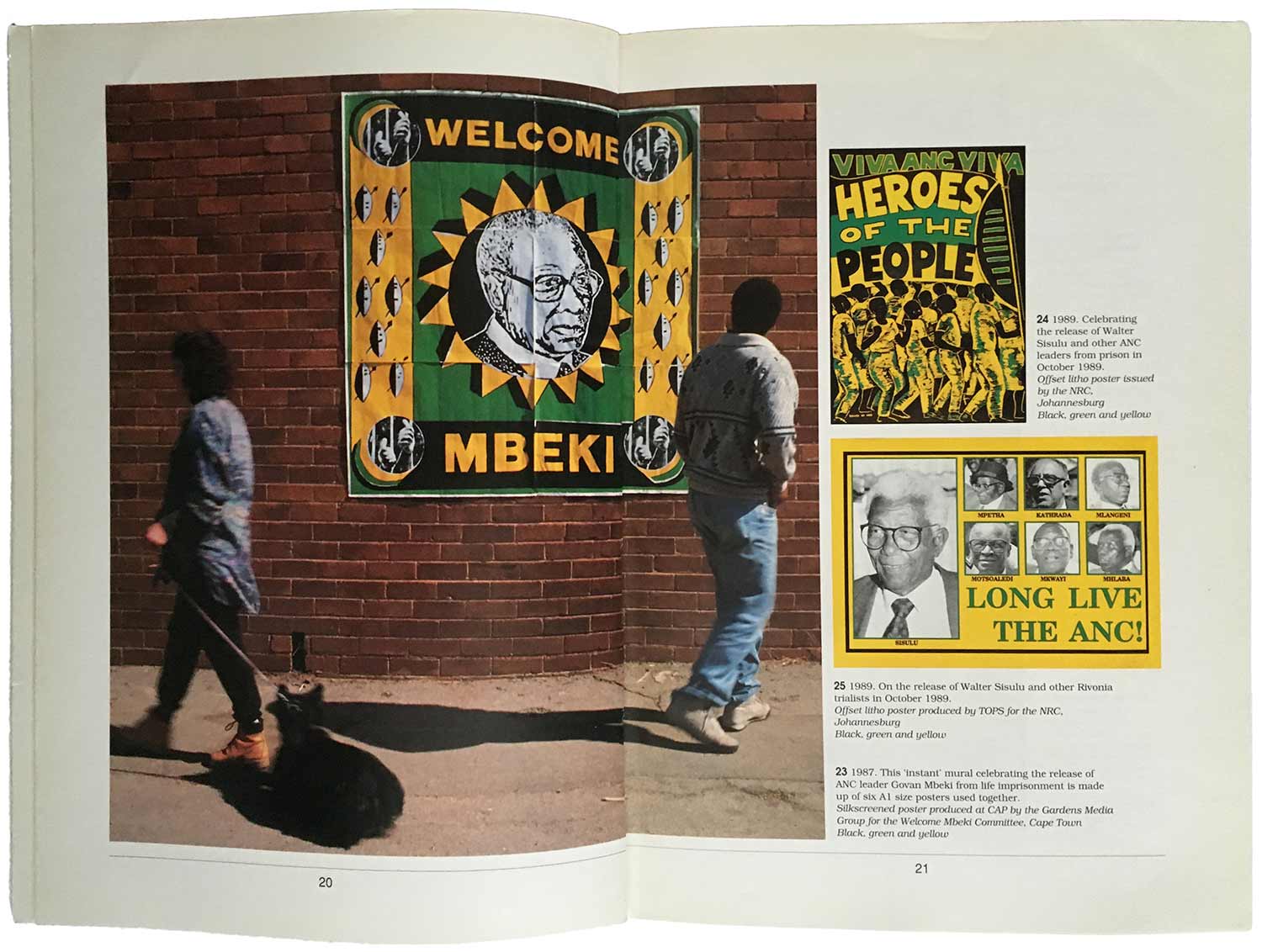

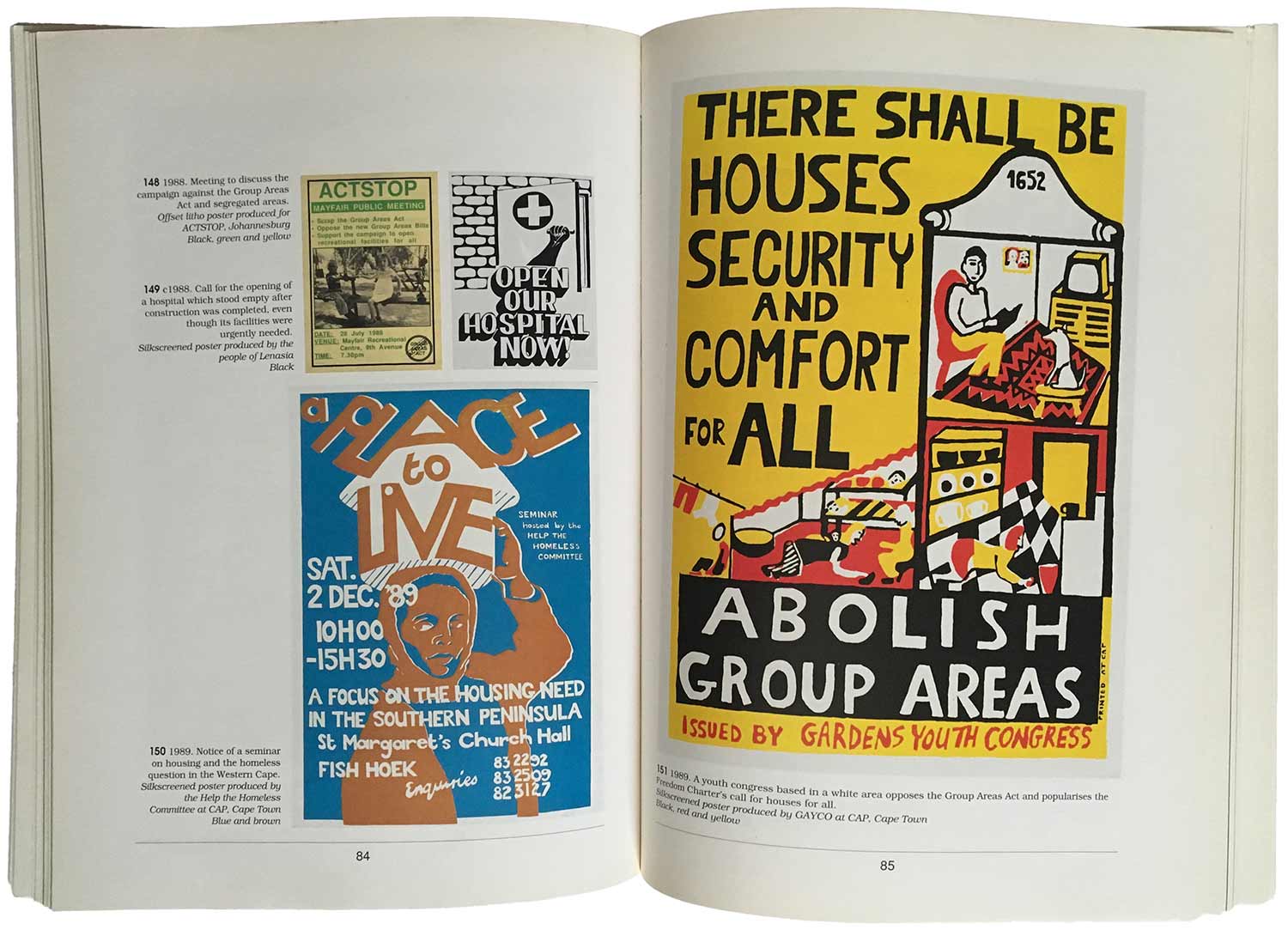

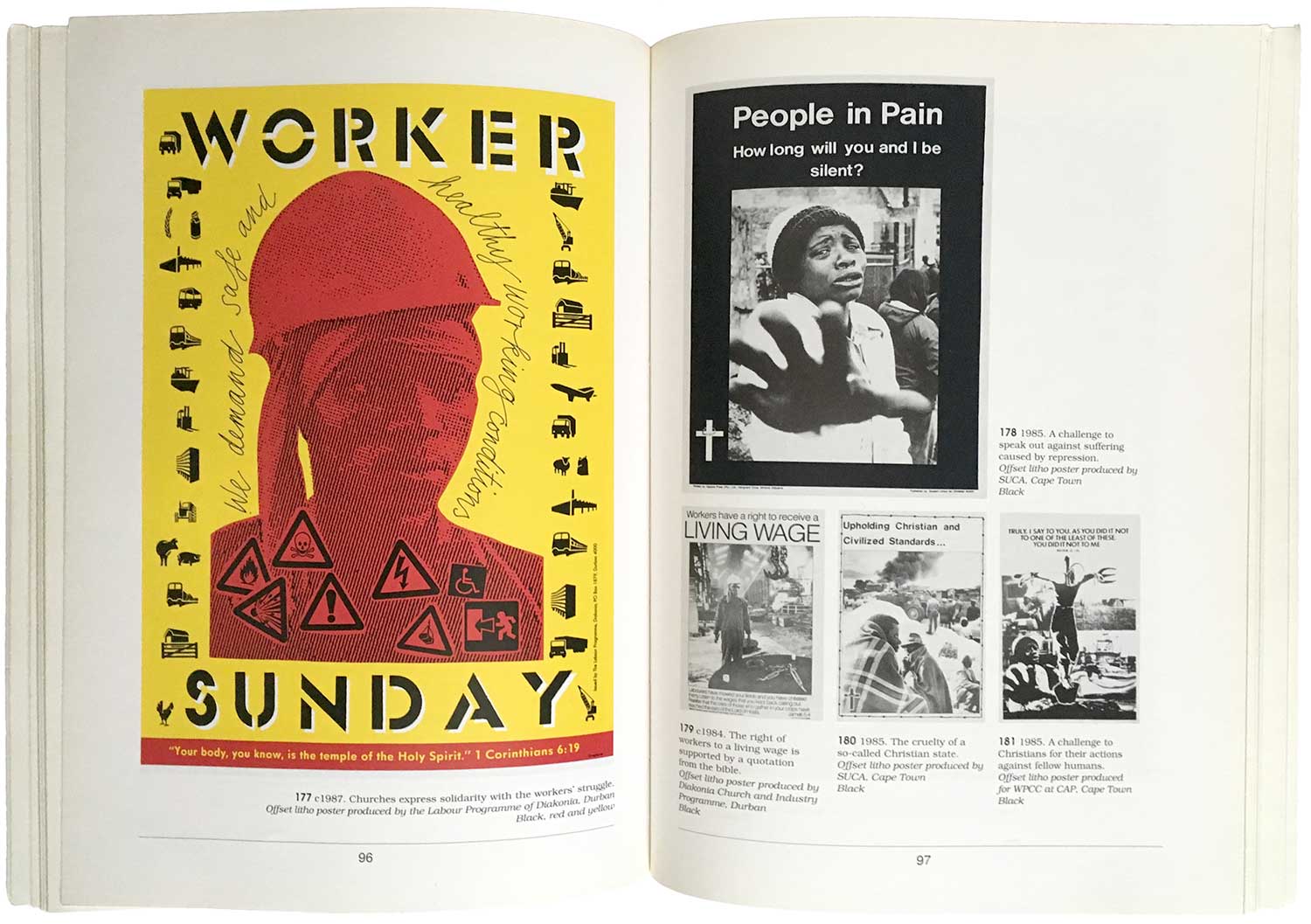

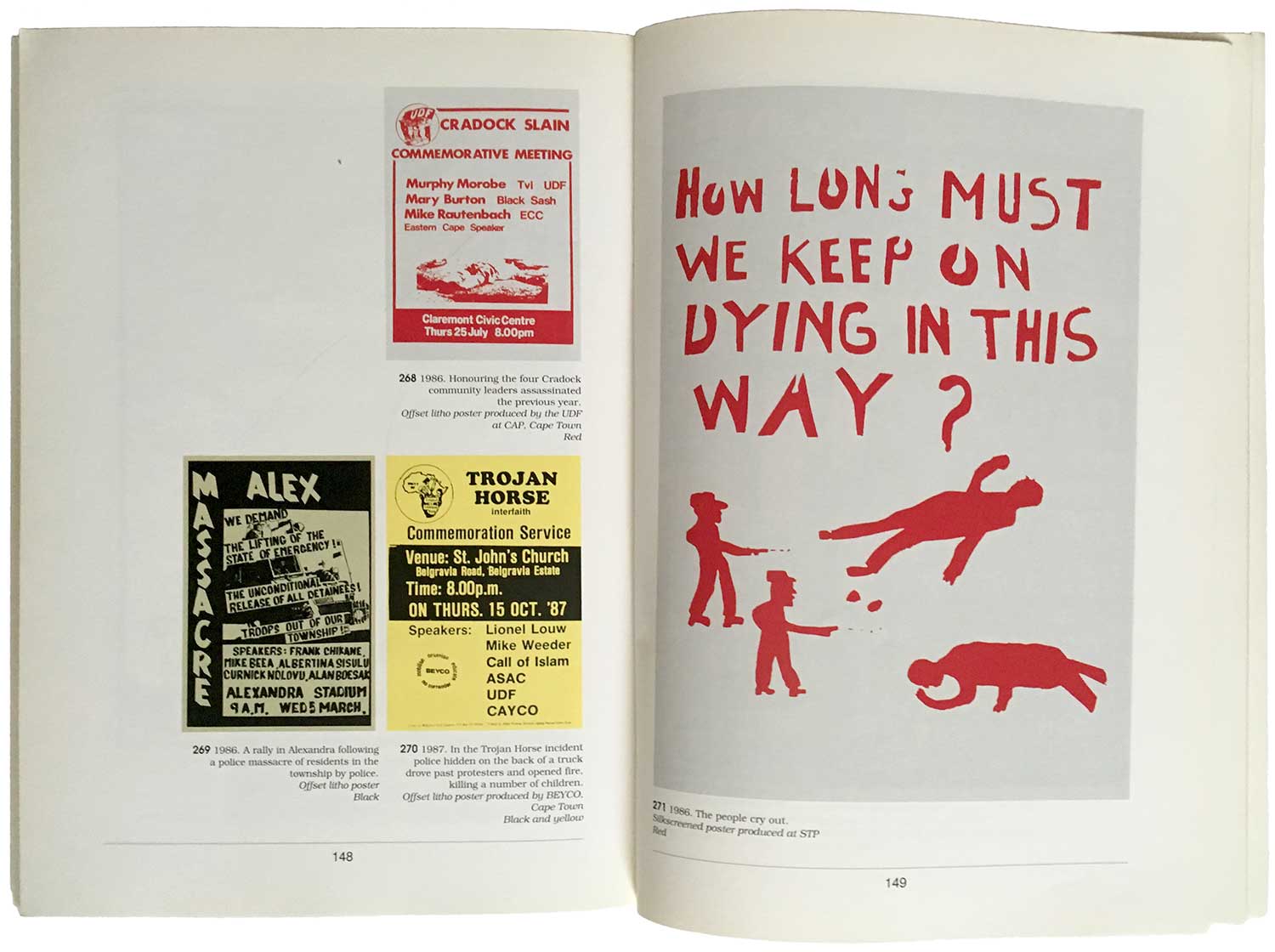

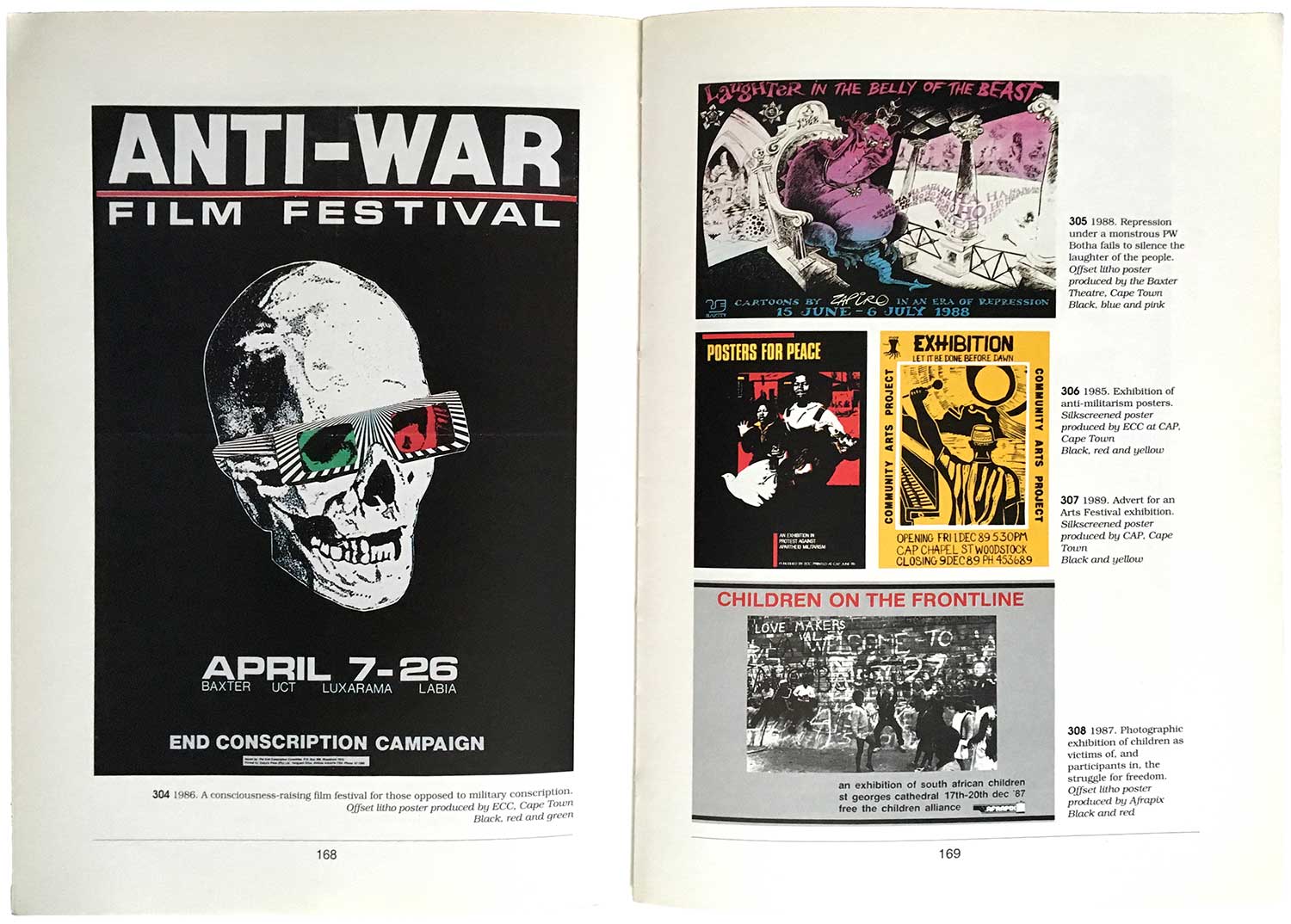

In addition to these relative standard trade paperback books, Ravan also did a great job (for a small publisher) in putting out more lavish, yet affordable, graphic and art books. The first Ravan title I ever say was a gift from a friend who had just returned from South Africa. Knowing me as a poster maker, she super thoughtfully brought me a copy of Images of Defiance, an amazing collection of hundreds of anti-apartheid posters. Edited by an ad-hoc group of artists and cultural workers calling themselves the “Poster Book Collective,” they’ve assembled one of the most complete collections not only of South African posters, but of the posters of any political movement.

They’ve done a great job of not simply focusing in on the posters that with hindsight we can see are well designed, but on the full range of production, from the most advanced and successful to graphics clearly produced by total amateurs. In fact, in the contextual and historical essays in the book they make it clear the importance for the struggle of poster production be accessible to amateurs, and the power of democratizing the means of production.

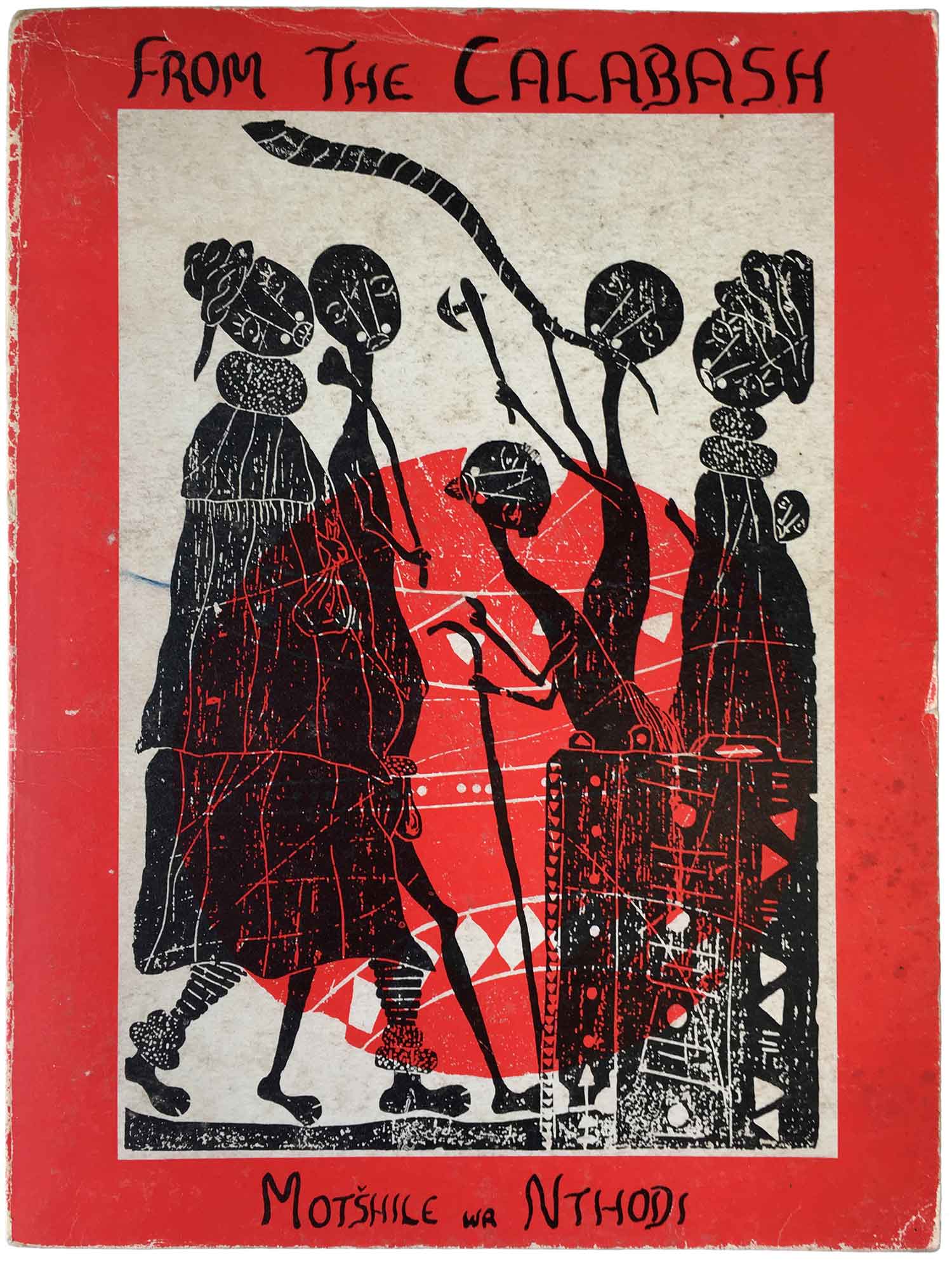

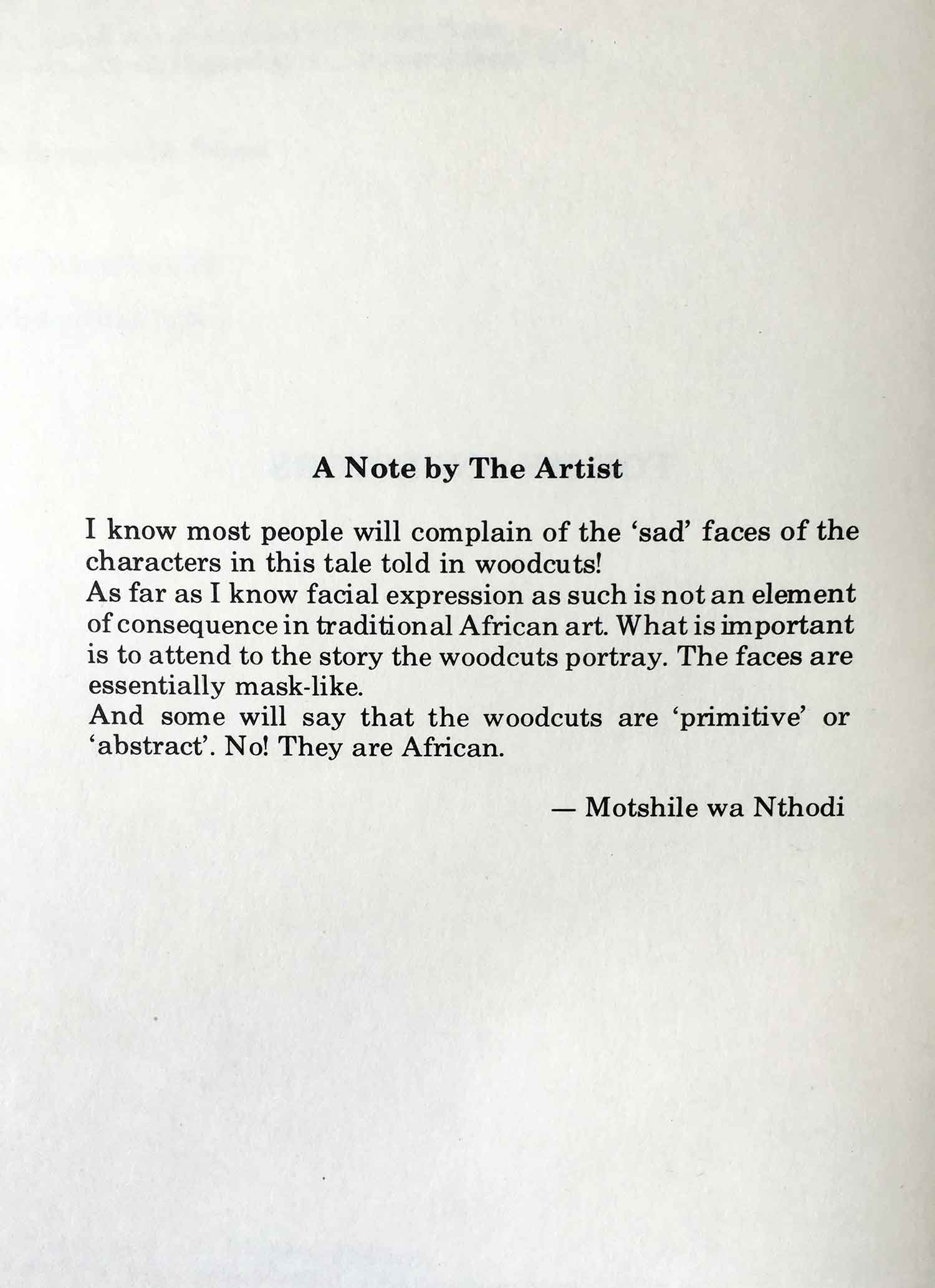

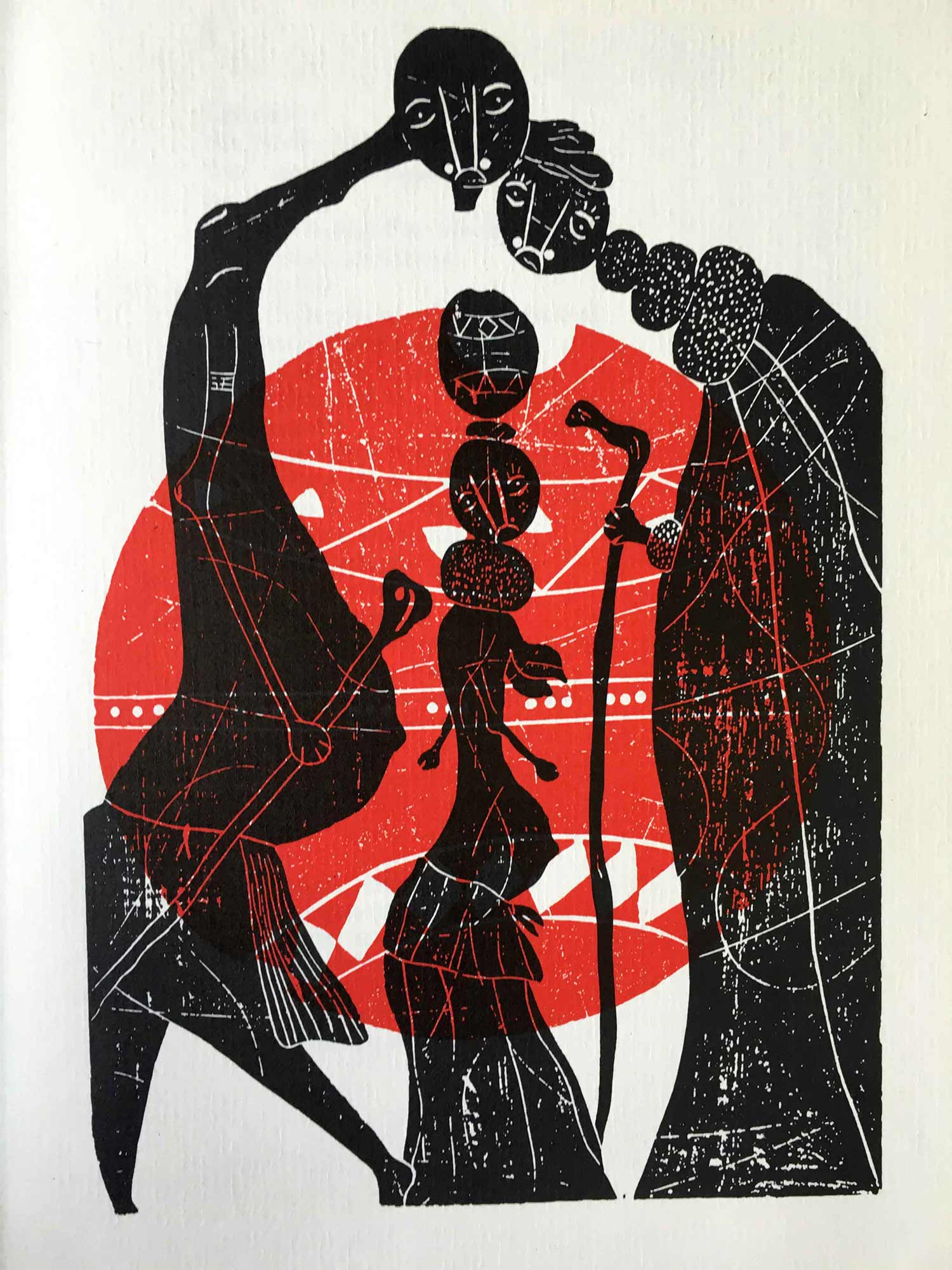

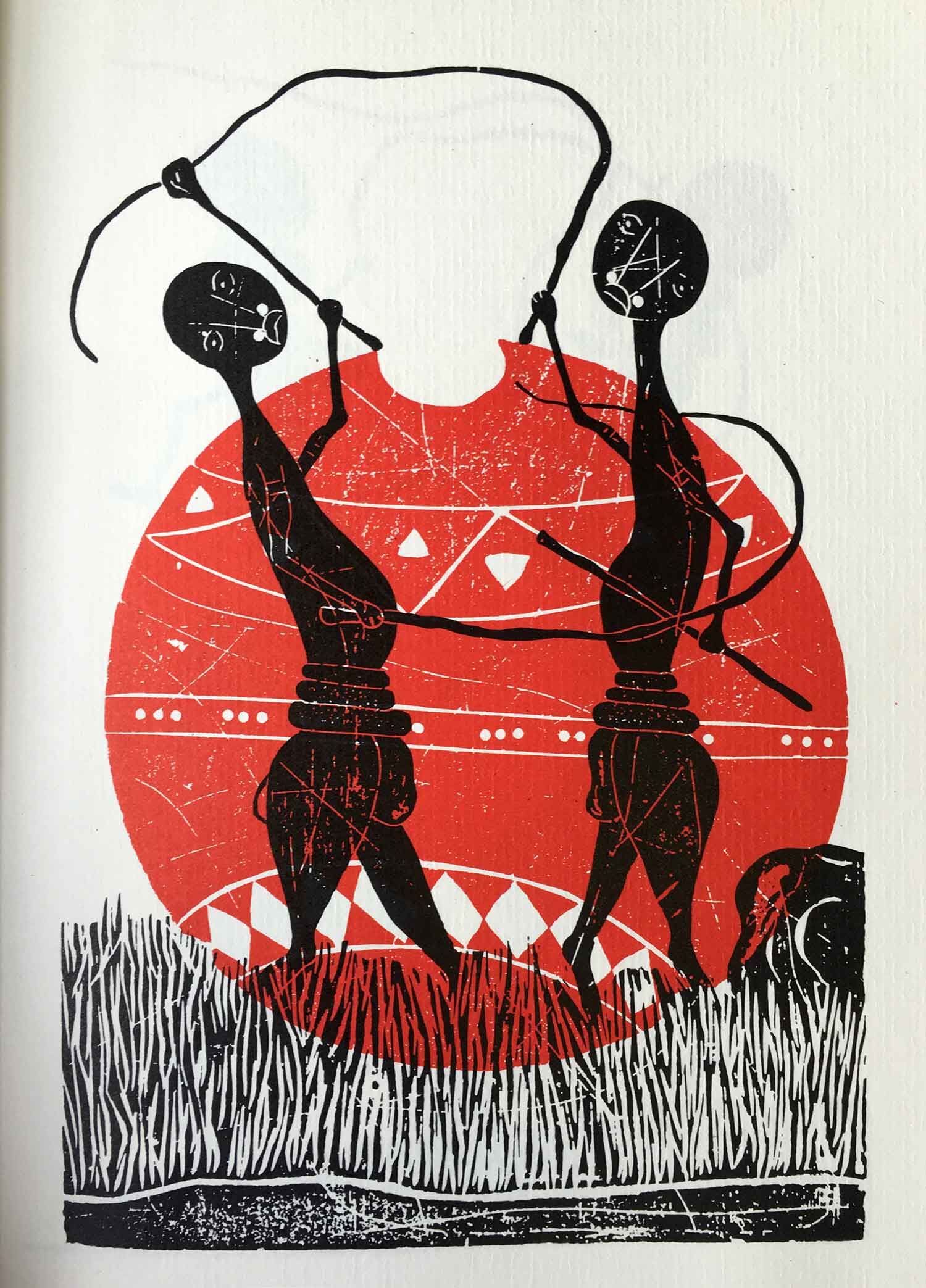

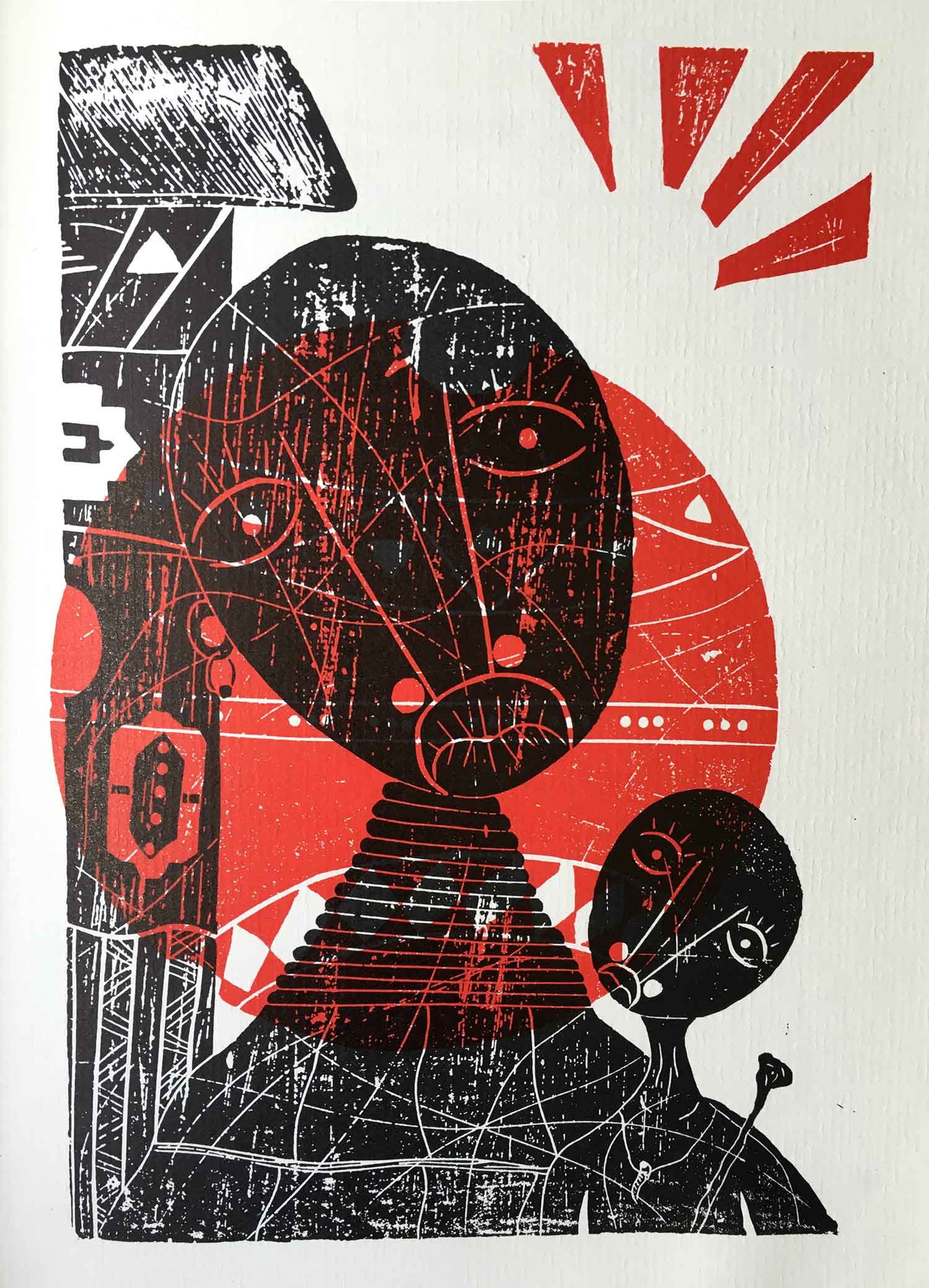

One of Ravan’s early book experiments was From the Calabash, published in 1978. It’s an impressive collection of writing and woodcut prints from the Motshile wa Nthodi. Each print is published on a thicker, textured stock in two colors. Each woodblock is composed of 2 elements: a calabash, printed in red in the background and a representation of both ancestors and the rural; and a composition of black figures, which represent life. It’s a beautiful book.

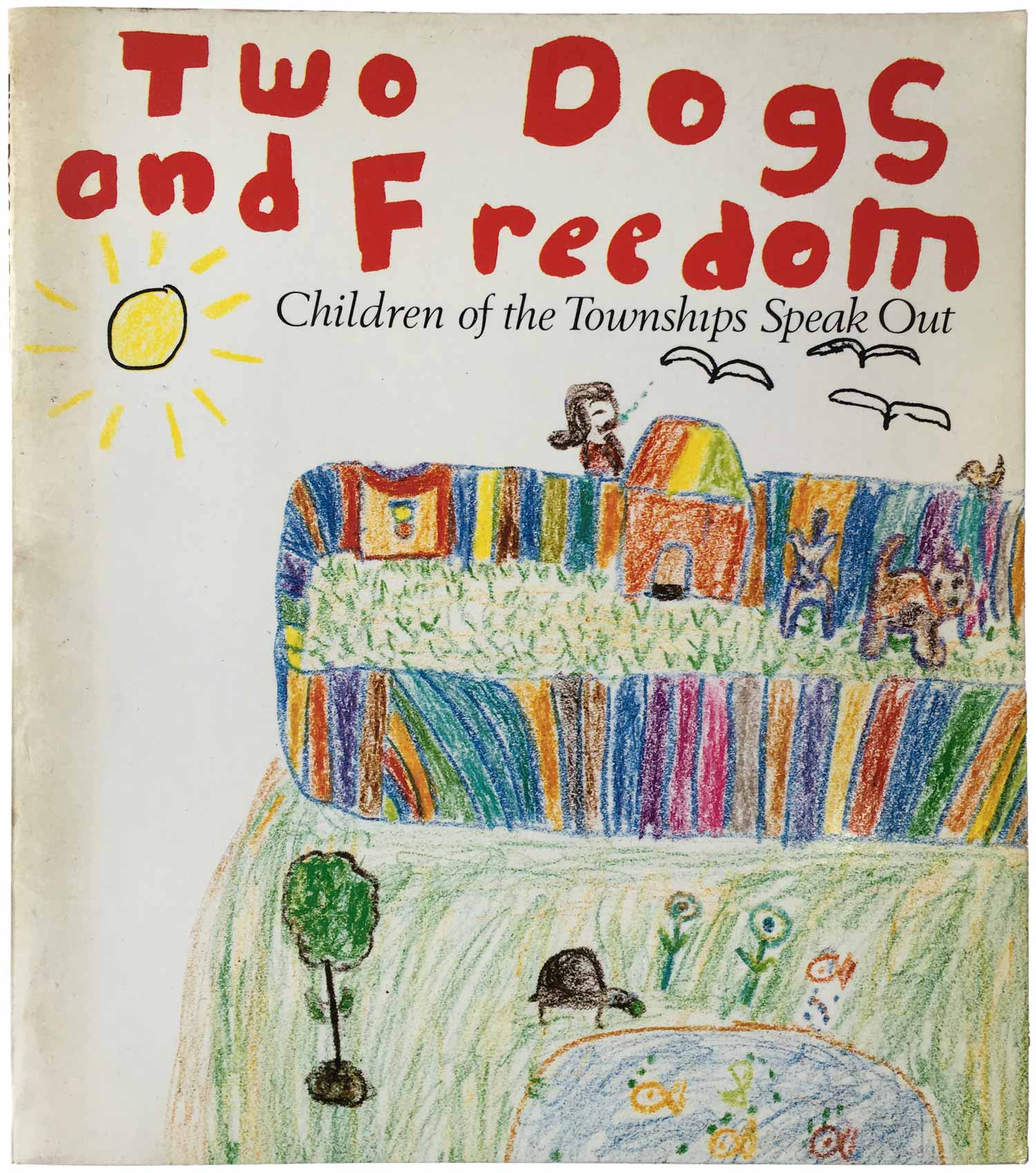

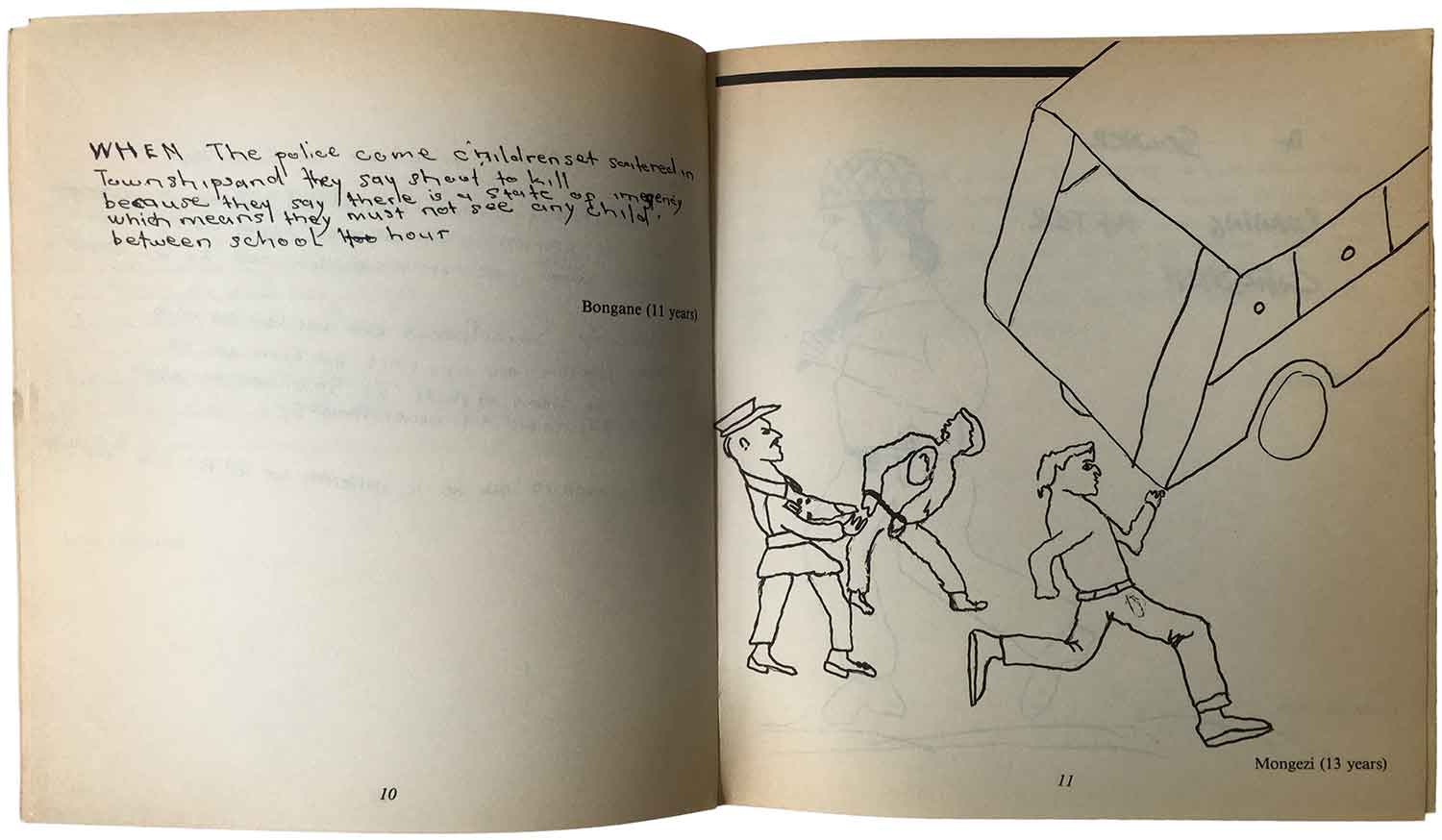

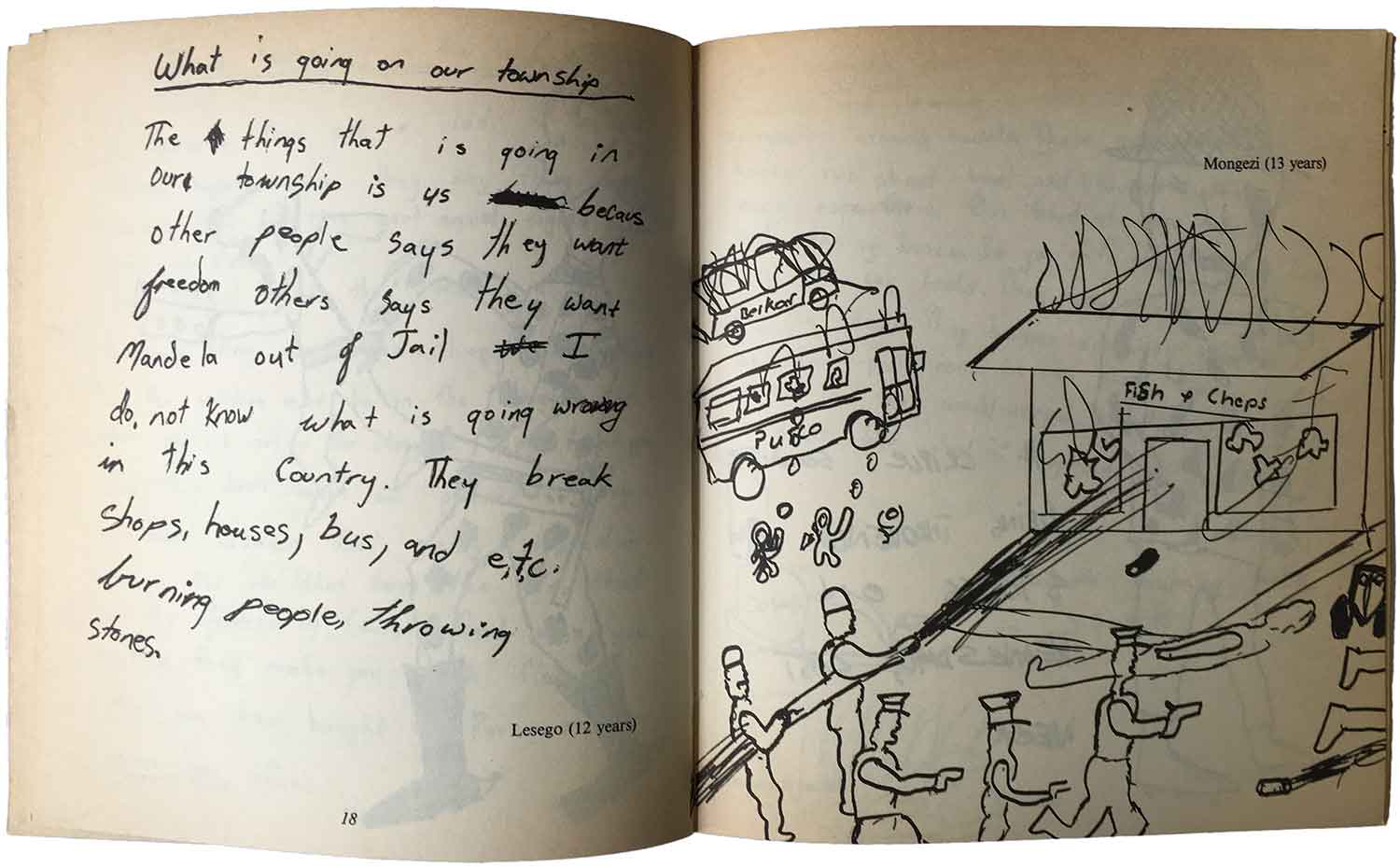

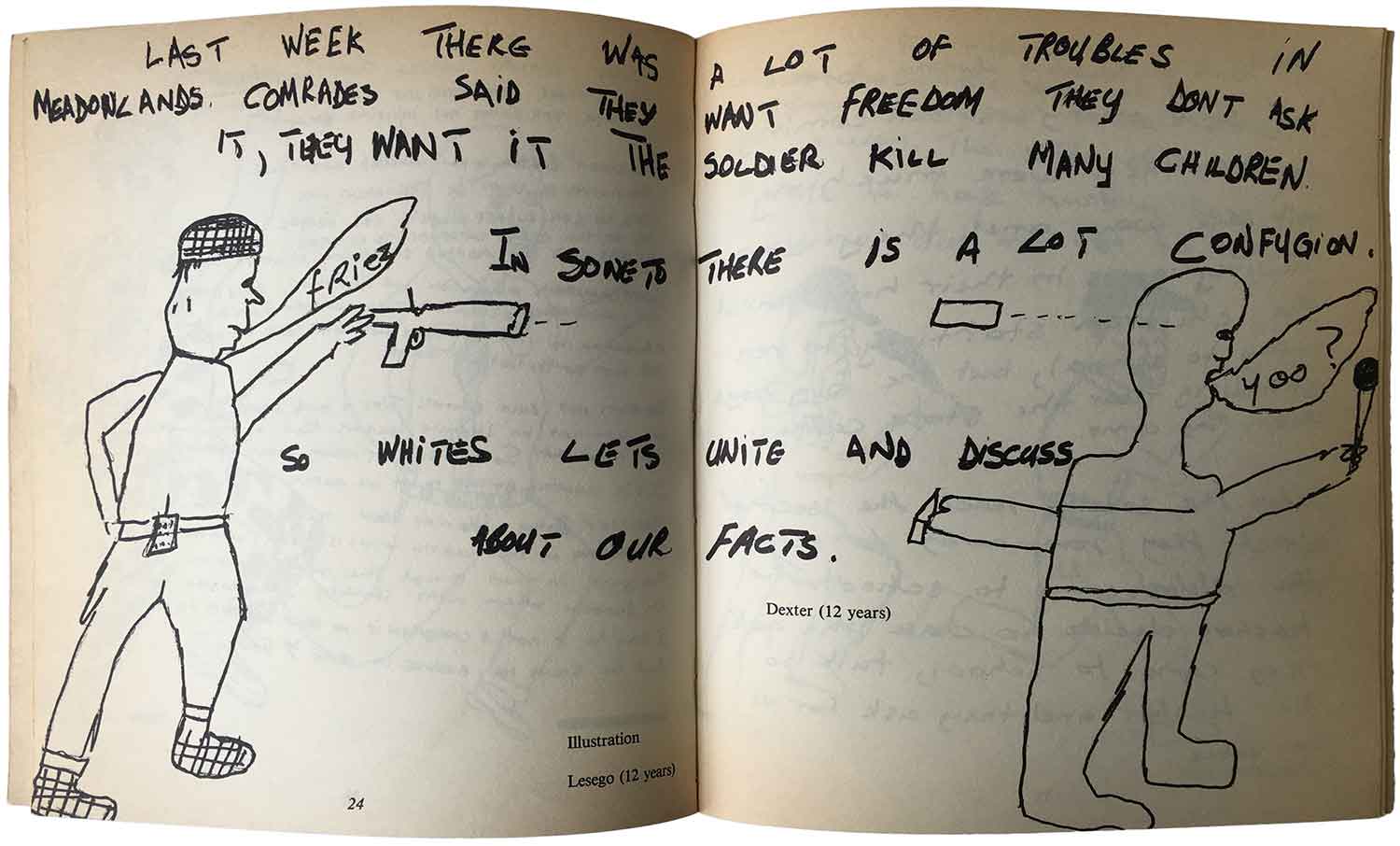

The last “picture book” I have to share is Two Dogs and Freedom: Children of the Townships Speak Out. The book is edited and compiled by The Open School, which was an alternative education project run by the Institute for Race Relations in South Africa for Black youth from the townships, with a focus on arts training. This book is a collection of drawings and writing by Black youth, and rather than cleaning them up and heavily designing the book, it largely is facsimile reproductions of the kid’s work. As you can see below, the work is both striking and powerful, especially in its direct depictions of violence.

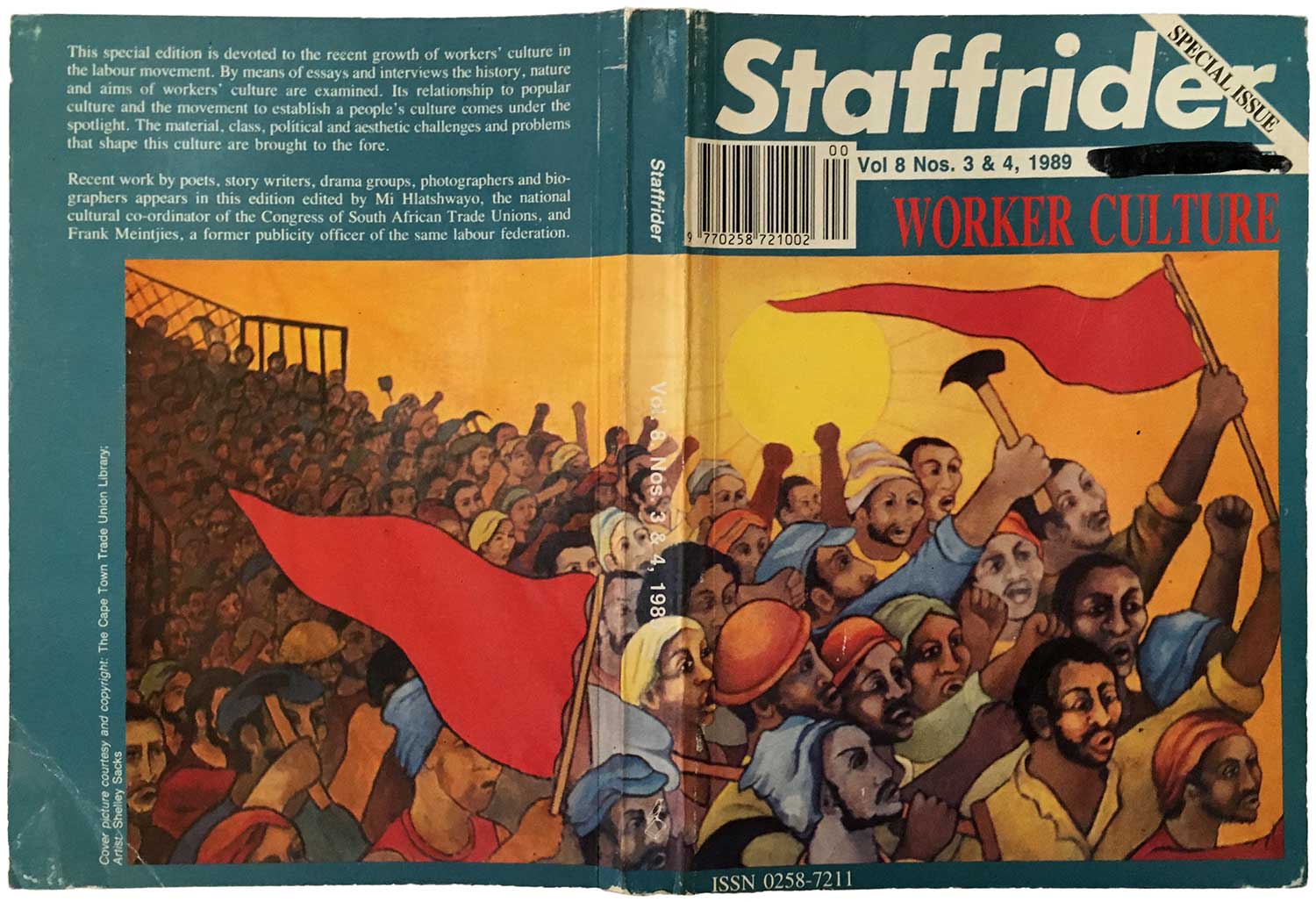

Staffrider was one of the most important magazines in 1980s South Africa. It was named after township slang for kids who caught illegal rides on the tops of commuter trains, and during the apartheid-era, it’s embracing of English as common language and it’s publishing of writing across the racial spectrum was seen as amazingly threatening. Although it was founded in 1978, in the wake of massive wildcat strikes by Black workers in Durban (inspired, in part, by the work of Steve Biko, but not affiliated with any official parties or organizations), a decade later it had settled in to becoming a voice for the largely ANC-dominated anti-apartheid movement. Staffrider was an outlet for writers not just across the racial spectrum, but also experience, publishing first time authors as well as people such as Nadine Gordimer. I’m unsure of the exact relationship between Ravan Press and Staffrider, but I know Ravan published some of the later issues in book format, such as the issue below. In addition, they shared some staff, including Ivan Vladaslavic as an editor. For those that haven’t had the pleasure, check out Vladaslavic’s novels—they are quite popular in South Africa, but he is sadly almost unheard of here in the U.S. His book Restless Supermarket is the best novel written about the fate and psyche of whites in just-post-apartheid S. Africa, it’s a must read.

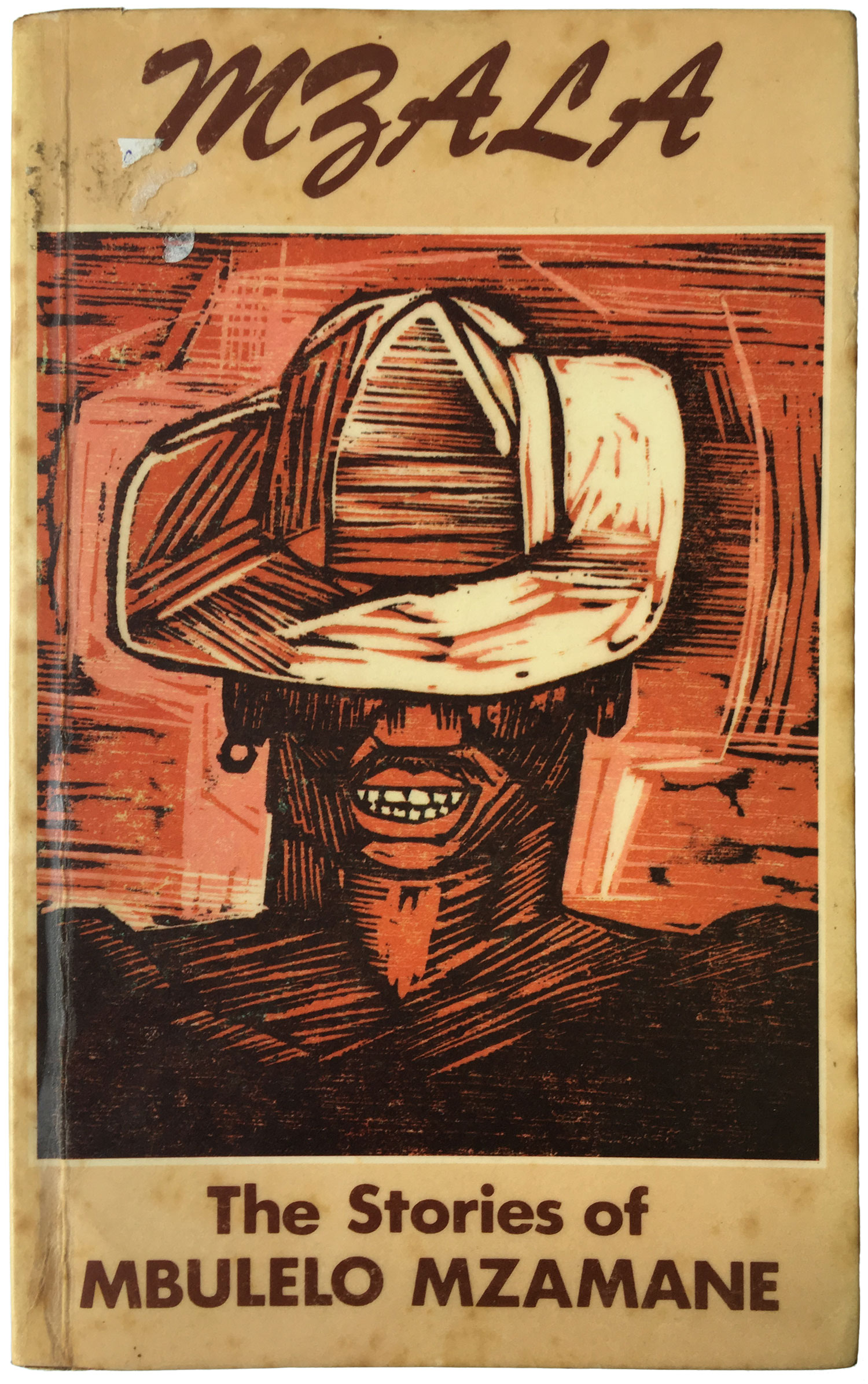

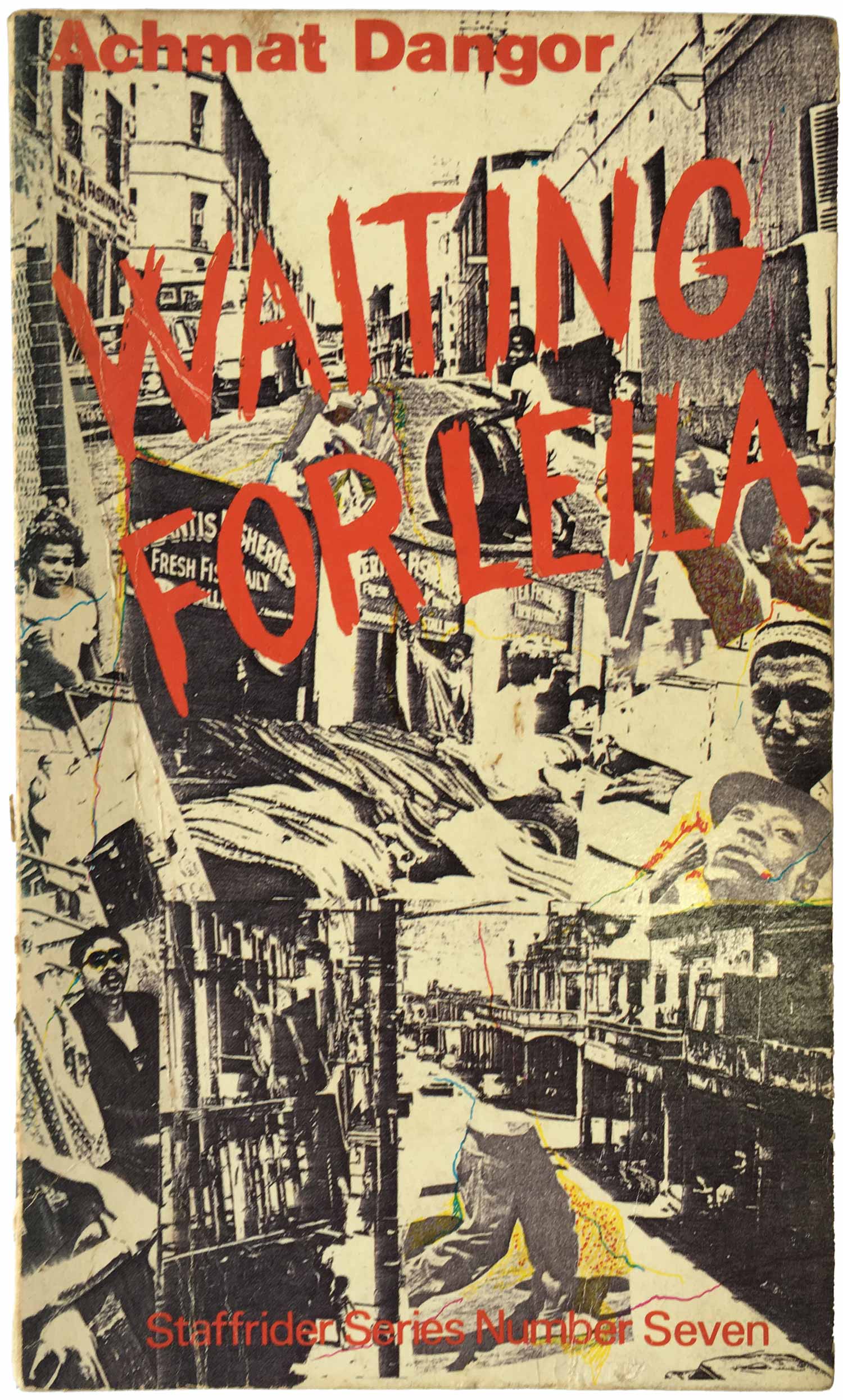

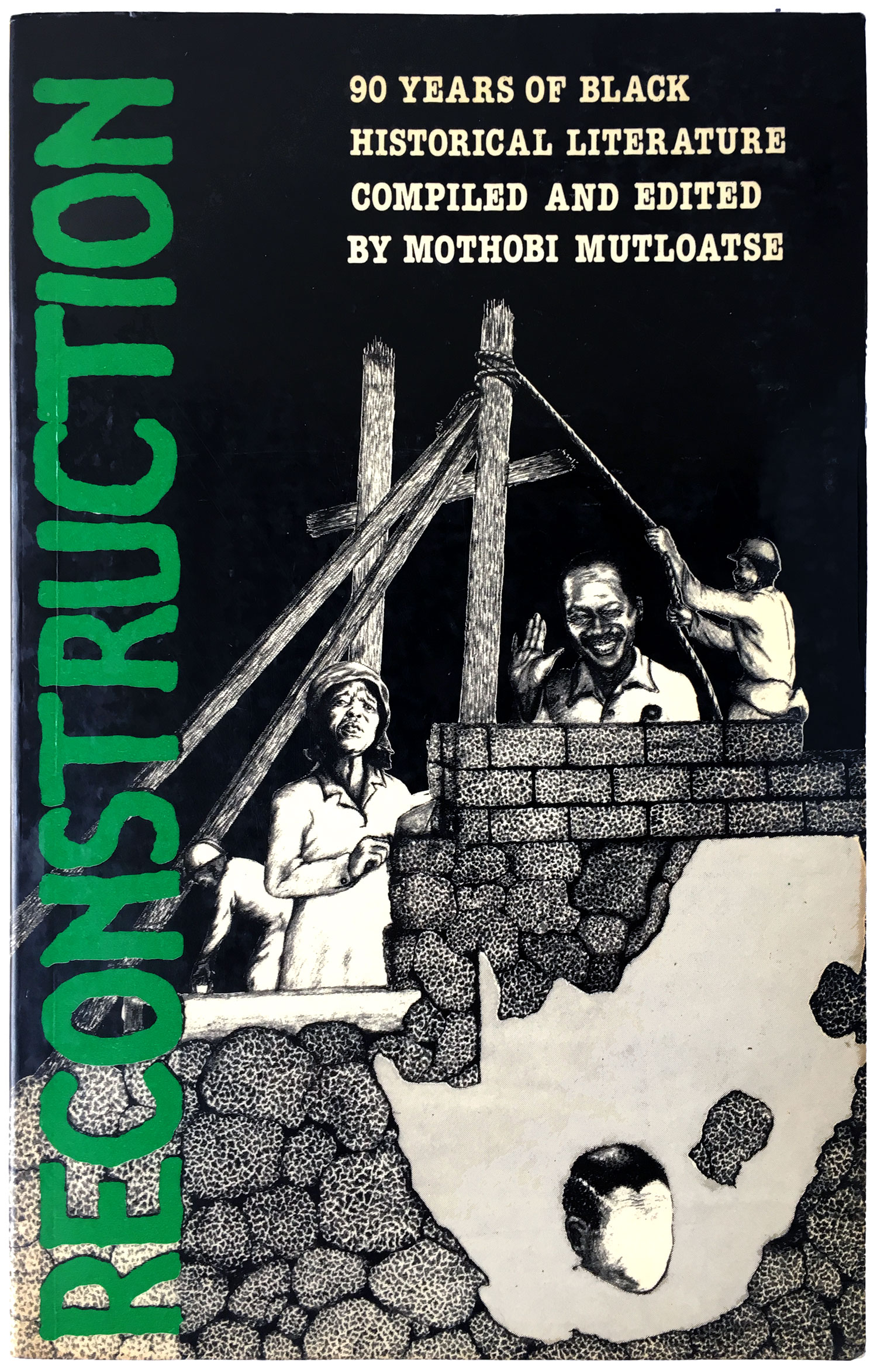

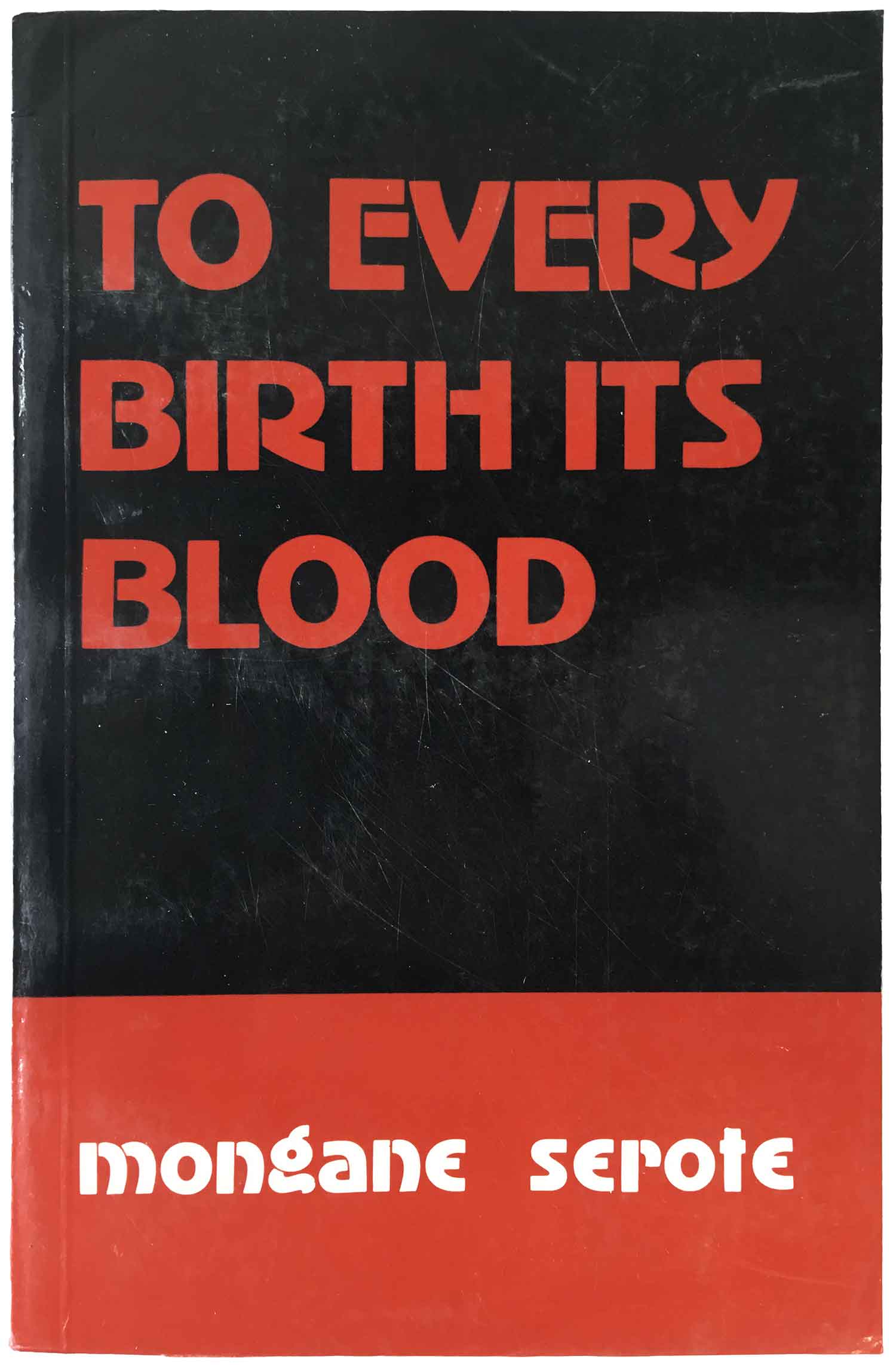

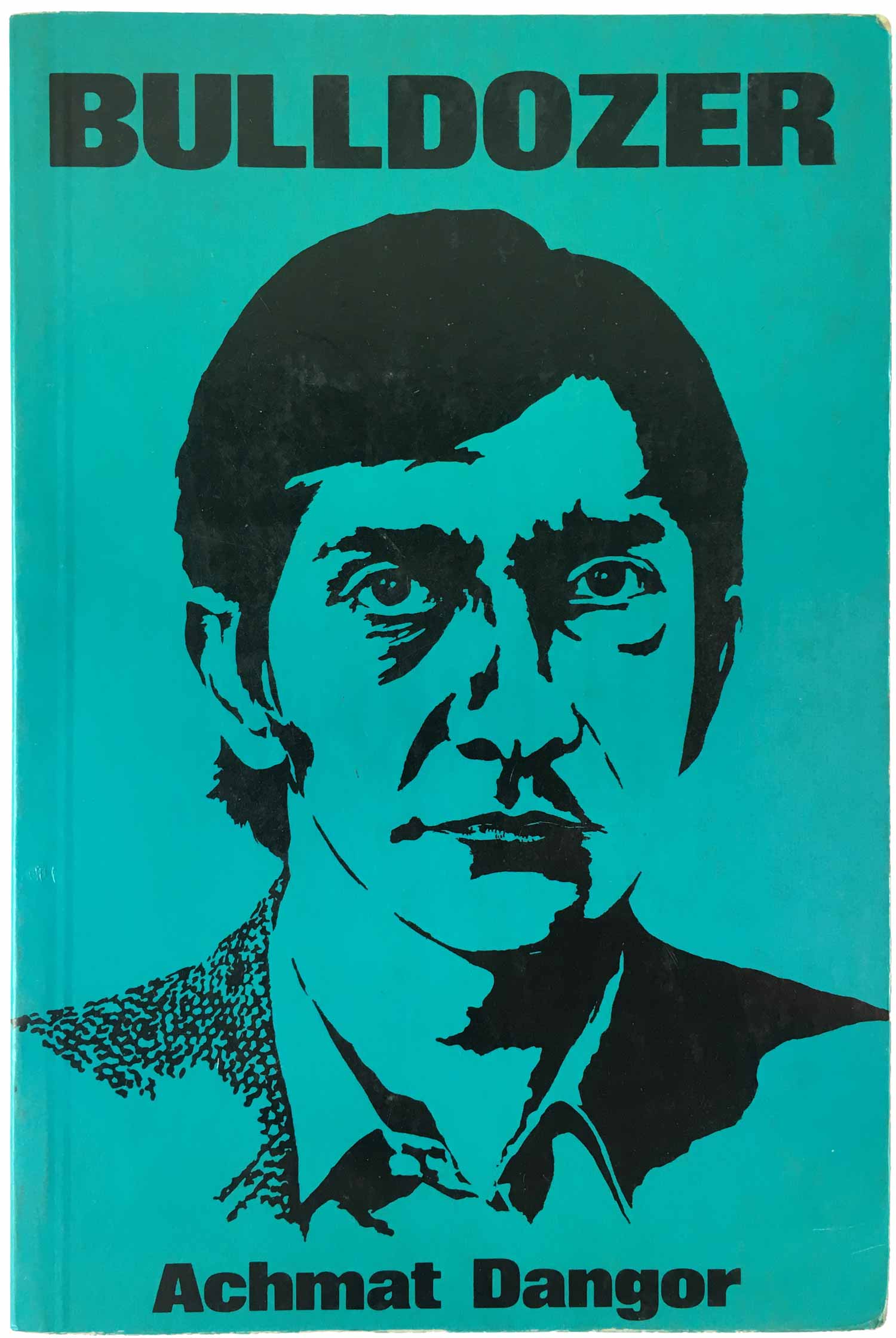

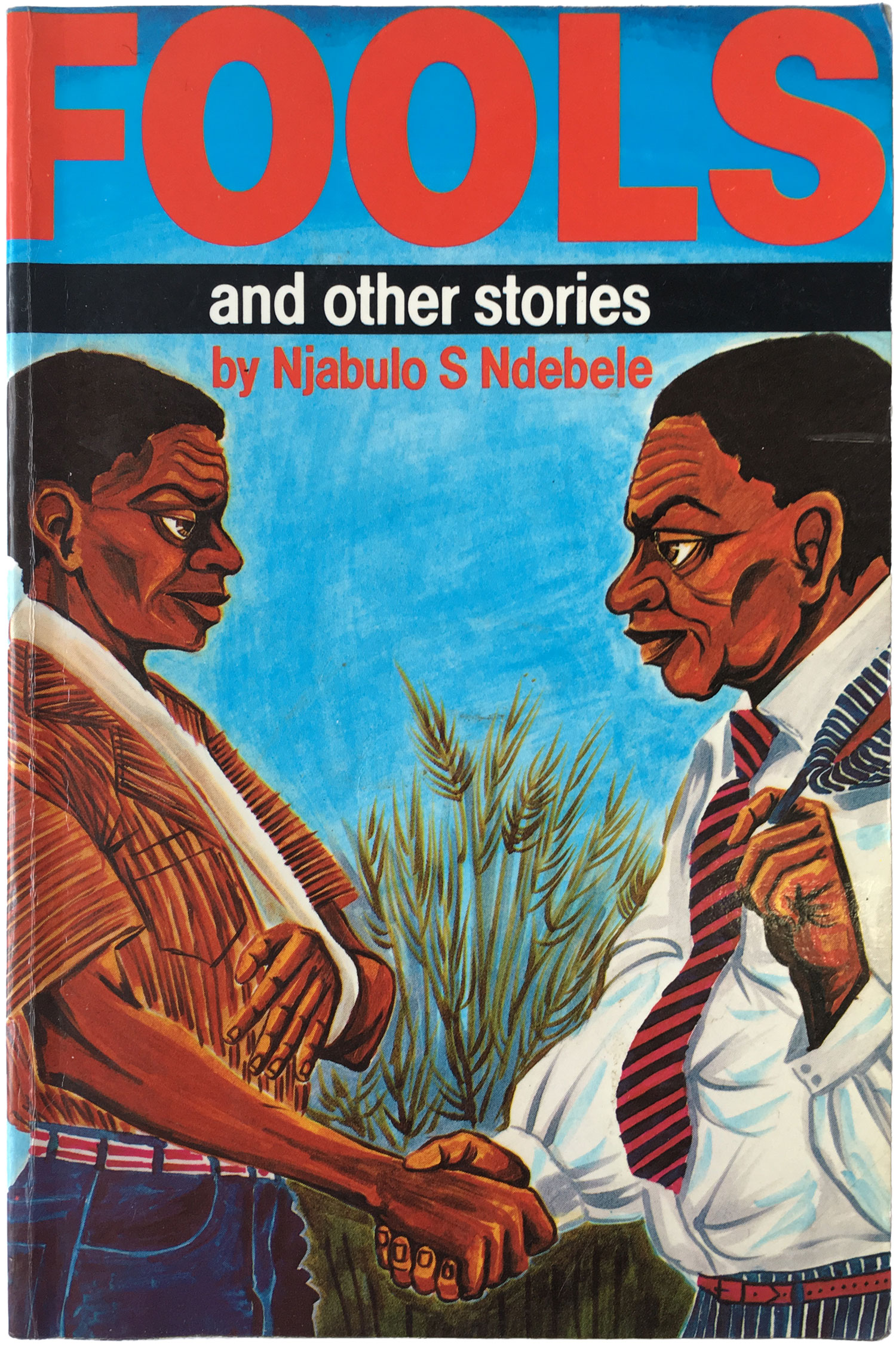

On top of publishing special issues, Ravan also published a collection of thirty something volumes of their “Staffrider Series”—books pulled together by the magazine’s editors of some of their most important authors and writing. These didn’t circulate much outside of the country—I’ve only got seven of the volumes, and half of those I got in S. Africa. As you can see below, for the most part these are handsome volumes, with simple type treatments and strong cover illustrations, almost always by artists who also worked with Staffrider. You can’t tell by the covers, but many of these books were banned at different points in S. Africa. It makes me wonder how this worked for Ravan, whether the ban upped popularity, and made it easier to sell the other books, or made their distribution increasingly difficult to manage?

I really like the design for Waiting for Leila above. In some ways it fails as a book cover—it’s hard for the eye to find a place to rest—but the image is so rich with content I keep wanting to go back to it. At first glance its a simple montage of photos, but the more you look, the more you see. Red, blue, and yellow threads emerge, as well as parts of maps and shapes, as if the photographic images are laid on, and obscure, a topography beneath. The cover for Dangor’s Bulldozer is almost the opposite, design-wise. A very bold and stencil-like portrait of the author sits in heavy black on a aqua background. It’s notable for its simplicity. The same could be said for the Serote book, except that it’s too simple, a graphic was definitely needed.

I’m not entirely sure when Ravan shut their doors, but they published for at least twenty-five years. They put out hundreds and hundreds of titles, this is just a very small sampling. As I find more, I’ll be adding them to this post. Ravan and other S. African publishers raise all kinds of questions for me about how apartheid actually functioned. On the one hand you had police firebombing community workshops, and on the other you had publishers putting out novelizations of anti-apartheid armed struggle. Somehow these things co-existed, making it feel like repression and resistance in 1980s S. African was a very uneven terrain.

Bibliography:

Ravan ceased being Ravan in 1996, although it published a few rather inferior titles after it was taken over and became an imprint of Hodder & Stoughton Educational Southern Africa.

Thanks Monica! Any additional contextual information is always very appreciated. Feel free to comment on this or any of the other S. Africa book posts.