The TV show Miami Vice ran from 1984–1990, closing out the decade with a slick, fashionable, multi-racial crime fighting duo that got to play it both ways—creating a sexy, alluring image of drug culture and also ending each episode with a win for the “good guys.” 1984 also saw the publishing of long-time crime novelist Charles Willeford’s first entry in his Hoke Moseley detective series, Miami Blues. While the two seem to be often compared, even in the blurbs on the Willeford novels, to me they couldn’t be further apart. There is nothing sexy or alluring about Willeford’s Miami, or his protagonist, for that matter. Vice is about action, in Blues it’s hard to figure out if anything actually happens. The sprawling go-nowhere plots of the novels are almost a mockery of Miami Vice—for Willeford Miami is a shambles: dirty, directionless, and full of clueless retirees and snowbirds uncomfortably rubbing up against jobless immigrants from the Mariel boatlift. Crockett and Tubbs cruise around in sports cars and designer cloths, Moseley is more likely to be spilling food on cloths he hasn’t washed for weeks.

He’s been called the Philip K. Dick of the crime genre, likely for both the quirky, downright weirdness of some of his writing, but also his refusal to stick to standard genre conventions. Willeford’s genius Cockfighter is another noir with no clear crime, taking the reader deeper than one would ever want into the pathos of the marginal and marginalized culture of cockfighting. He also wrote Westerns, and books like The Pick-Up, a rambling, almost plotless story of a down-and out character with a twist at the end that completely transforms the reading of the book. One of my favorites is The Burnt-Orange Heresy, a hilarious 1970s take-down of the simultaneous commercialization and hollowing out of meaning within the world of modern art, years before anything close to Willeford’s level of insight and critique was being circulated within art circles.

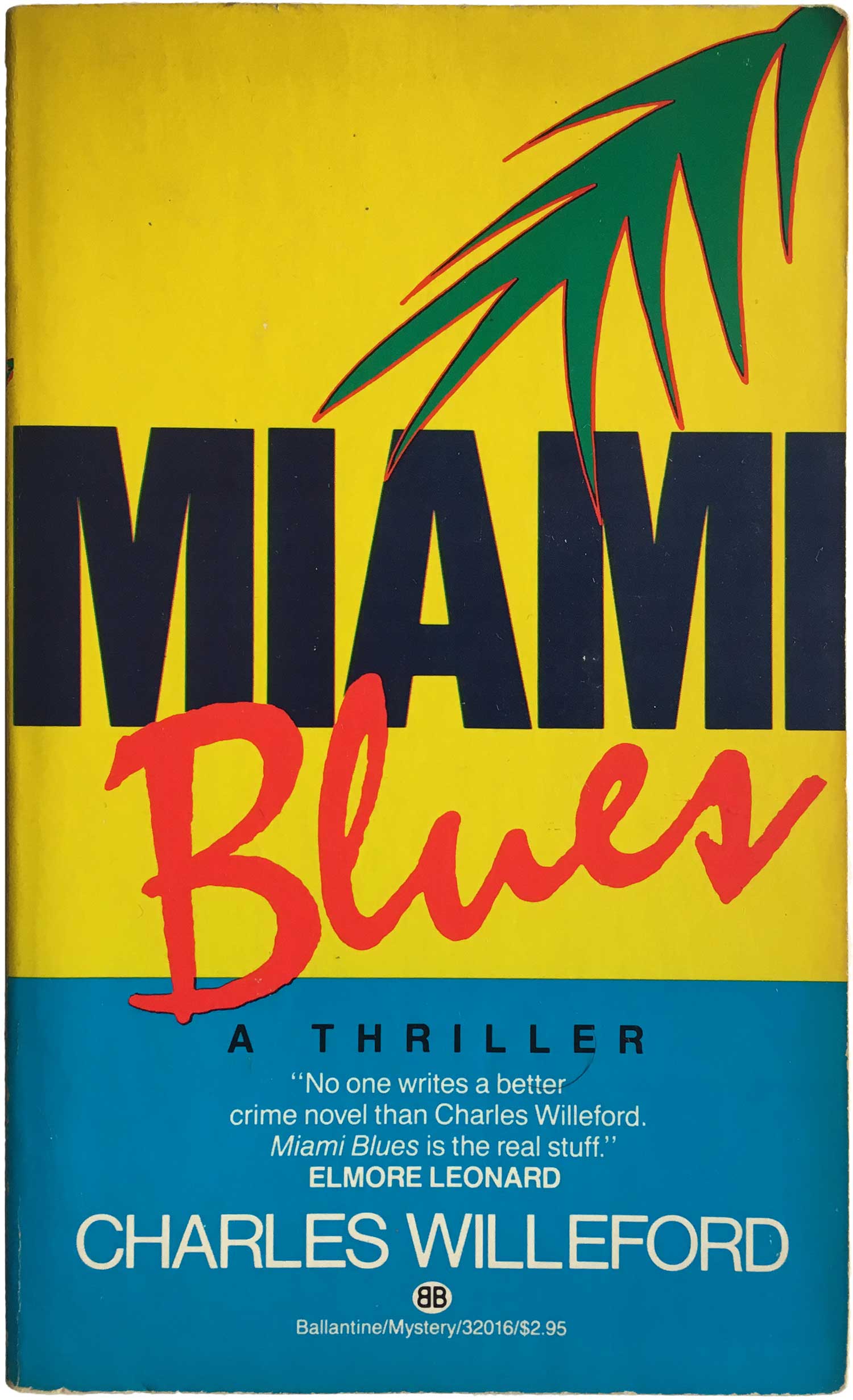

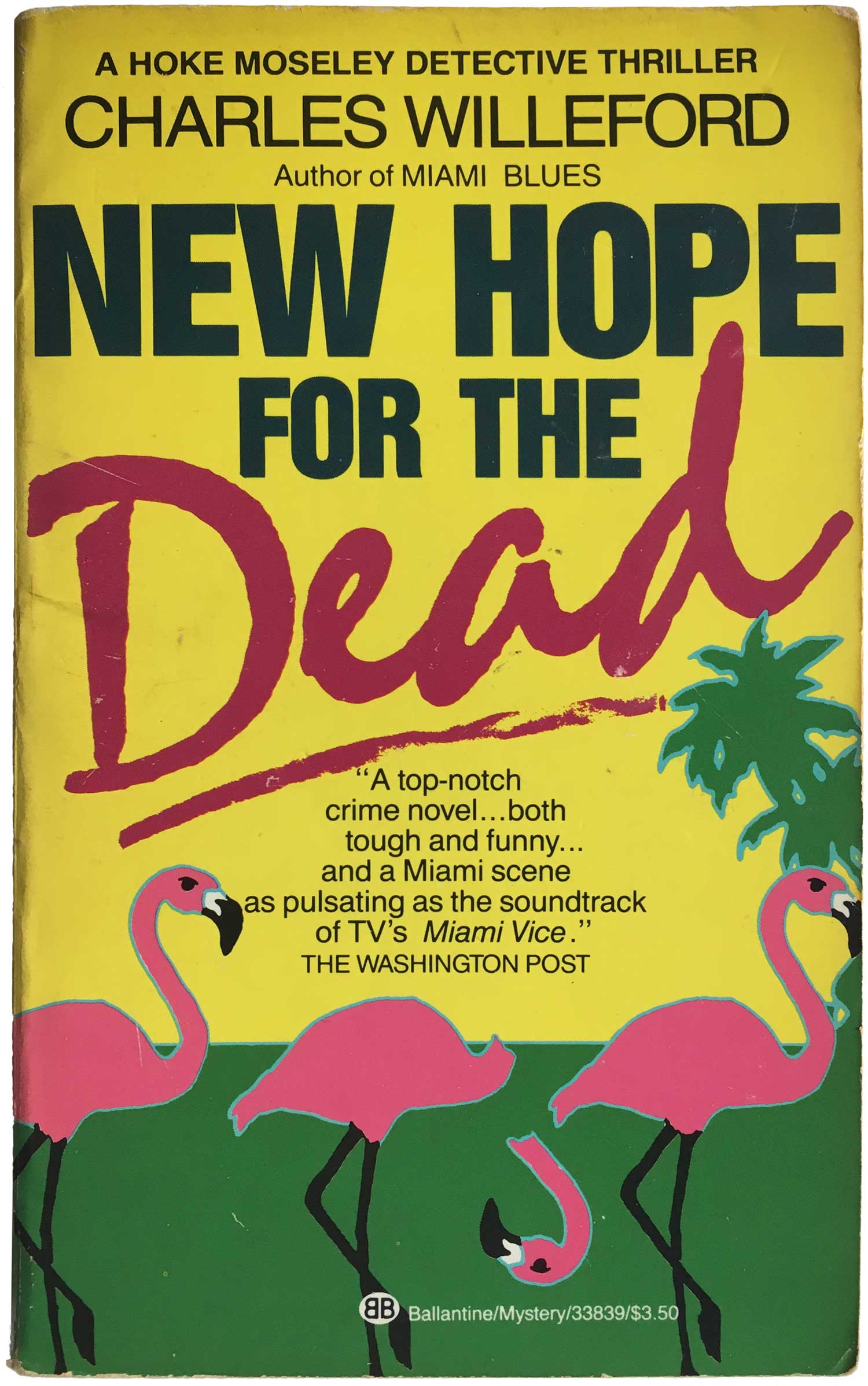

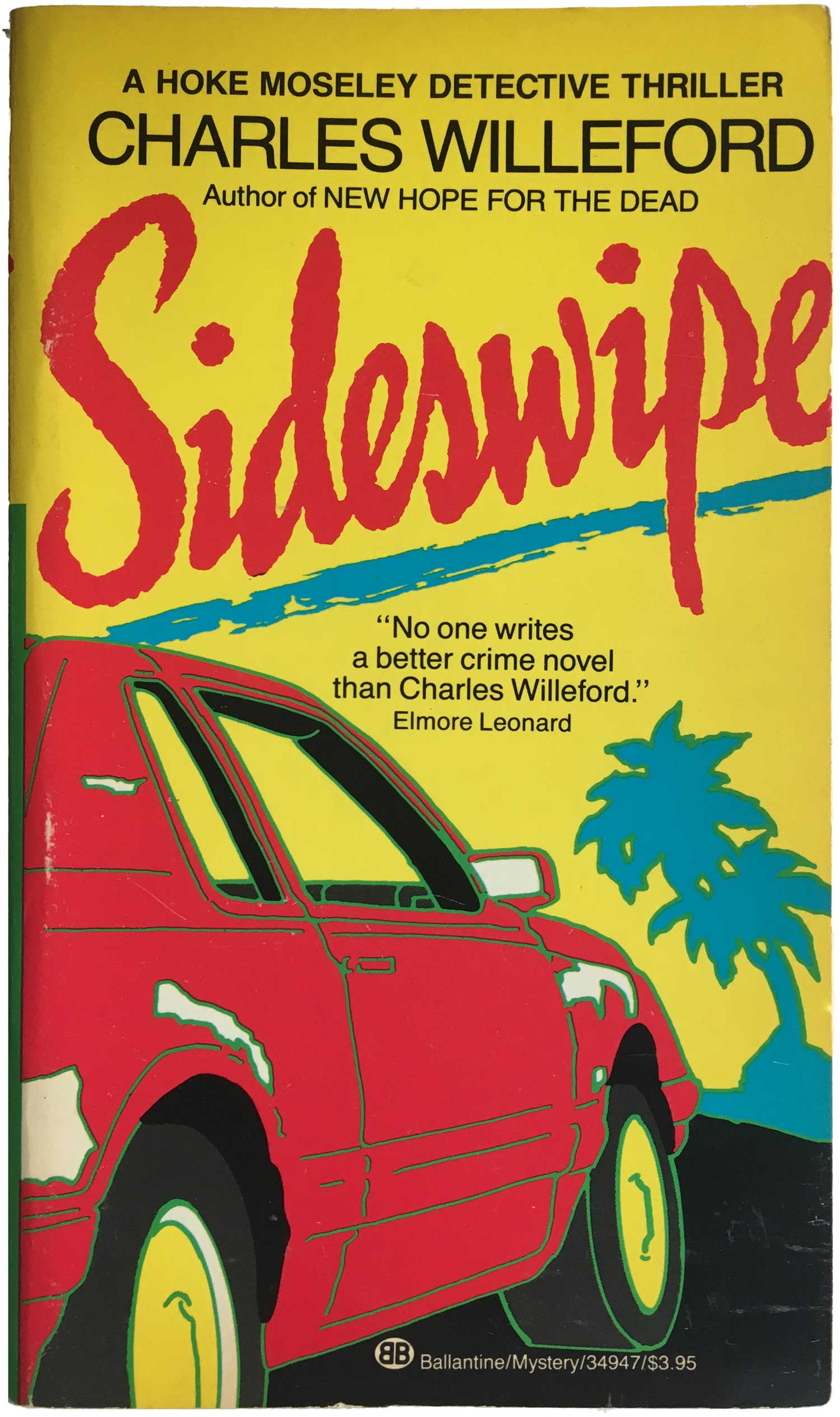

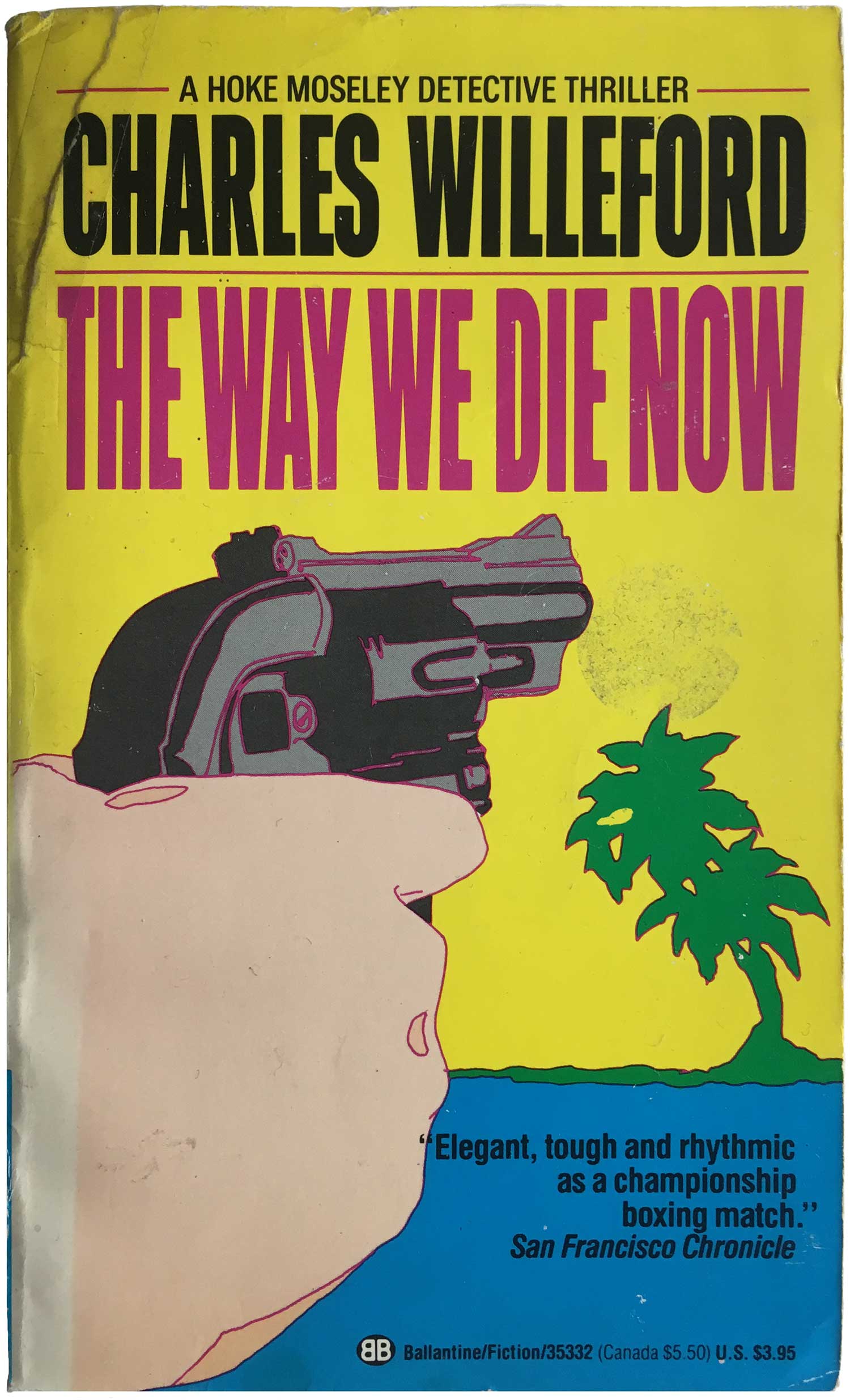

Back to the books at hand. The Moseley series was released in cloth by St. Martins Press (except the final novel, The Way We Die, released on Random House), but I’m really only interested in the first mass-market paperback editions, each published by Ballantine Books a year after the initial hardback release. It’s criminal that the designer of the set isn’t credited anywhere, and my cursory research hasn’t turned up a name. The covers are all great. Not only do they catch the eye and distinguish the series from other books, but they double as twisted neon pop-versions of Florida, with broken flamingos, guns aimed nowhere, and the same flat, cut-out palm tree haunting three of the four designs. Although the trees, pink flamingos, and yellow-drenched backgrounds signal “Miami” loud and clear, the stripped down nature of the designs also gives a sense that these books take place nowhere—as if Miami is purely a figment of pop culture imagination, with nothing “real” marking it as distinct or unique. As if Miami itself has swallowed the myth of Miami, leaving little else to hold onto.

Usually I’m just focusing on covers here, but this time around I really encourage people to check out Willeford’s book. They’re strange in a good way, without being onerous to read. If you just go along for the ride, I doubt you’ll be disappointed.

Books shown in this post:

Charles Willeford, Miami Blues (New York: Ballentine Books, 1985).

Charles Willeford, New Hope for the Dead (New York: Ballentine Books, 1987).

Charles Willeford, Sideswipe (New York: Ballentine Books, 1988).

Charles Willeford, The Way We Die Now (New York: Ballentine Books, 1989).