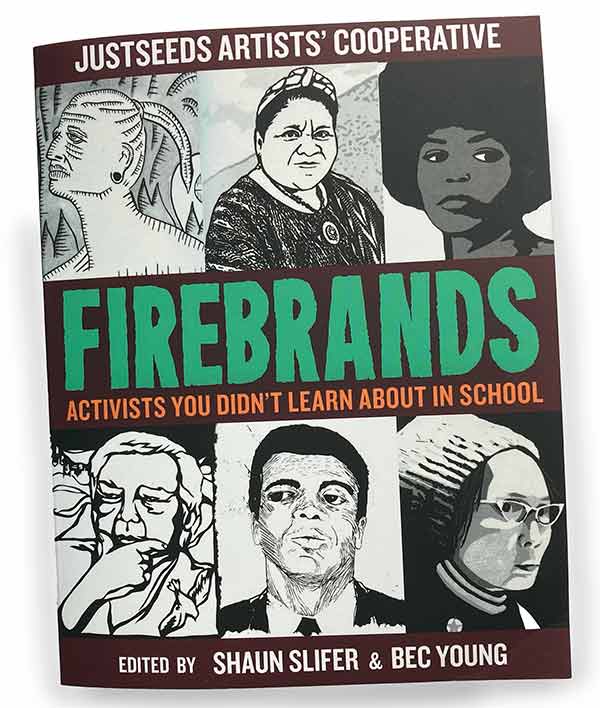

A new excerpt from A People’s Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice Movements that was published by The New Press. This excerpt looks at ACT UP and the design collective Gran Fury that is hands down one of the most important groups for activist artists to study today and to adapt various tactics (especially their structure) to today’s struggles. Here is the excerpt:

ACT UP

In early March 1987, more than three hundred gay and lesbian people gathered in New York City and founded ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). ACT UP’s mandate was specific—“medication into bodies”—free access to antiviral drugs to help those who were infected and more public awareness to stop the spread of AIDS. ACT UP embraced direct action as the primary way to respond to the AIDS crisis, to force the government, pharmaceutical companies, and the media to respond. Each meeting began with members stating in unison that they were “united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” These words were quickly backed up in practice.

The first ACT UP/NYC demonstration took place just two weeks after the founding meeting. On March 24, hundreds gathered at Wall Street to protest the FDA’s slow approval process for drugs and the collusion of government and corporate interests that profited from the manufacture of AZT, the only FDA-approved AIDS drug, sold by the pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome. AZT was a double negative; it was highly toxic and incredibly expensive. AZT cost patients more than $10,000 a year, despite the fact that the government had subsidized Burroughs Wellcome to develop it.

During the protest, activists blocked traffic in the streets, an effigy of FDA commissioner Frank Young was hung, and seventeen people were arrested. In the aftermath, the demonstration made national news and CBS newsanchor Dan Rather credited ACT UP for bringing national attention to the issue. Several weeks later, the FDA announced plans to speed up its drug-approval process, and in December, Burroughs Wellcome announced plans to drop the price of AZT by 20 percent. The stunning success of the Wall Street action placed ACT UP at the forefront of the AIDS activist movement. In a short time, more than a hundred ACT UP branches were formed in cities across the United States and abroad, although the NYC branch would remain the most visible of the chapters.

Structurally, ACT UP was organized into a series of committees that allowed people to engage with the group depending upon their talents and interests. Gregg Bordowitz of ACT UP/NYC explains:

ACT UP [NYC] was not one monolithic institution. It was a group of people who met every Monday night. Many of them were parts of smaller groups, or cells, or affinity groups within the larger group. And those affinity groups to some extent had, if not a separate life, a life outside the group.

Committees included, among others, a steering committee, a coordinating committee, and a women’s caucus. A majority caucus was formed in late 1987 because African Americans and Latinos represented the highest percentage of AIDS cases in NYC. For many, ACT UP be- came their social circle, dating scene, extended family, and way of life. Members would often go to different committee meetings nearly every night of the week.

ACT UP was also home to numerous art collectives that marked the organization from the very beginning. Michael Nesline, who was a member of the art collective Gran Fury, re- calls how members of the Silence = Death Project first introduced themselves to the group:

Avram [Finkelstein] stood up and said, “I’m one of the people that made those posters [Silence = Death]. Most of us are in the room. We talked about it after last week’s ACT UP meeting, and we decided that we want you all to know that we made those posters and we want ACT UP to be able to use that poster and that image for whatever purposes ACT UP deems appropriate. So, it’s yours.”

The image would quickly be put into action, including during the New York City Gay Pride Parade on June 28, 1987. ACT UP blanketed the march with the logo on T-shirts and signs carried in the parade. Nesline explains:

What the media was impressed by was the uniformity of our presentation. I mean, all of the posters are black posters with big pink triangles. It looked really organized. That was not a completely conscious strategy at that point. It quickly became a conscious strategy, because we realized that it worked, for the media.

But the images and slogans were not aimed just at the media and spectators. Cultural critic and ACT UP/NYC member Douglas Crimp argues that the primary audience for the graphics was people within the movement:

AIDS activist graphics enunciate AIDS politics to and for all of us in the movement. They suggest slogans (SILENCE = DEATH becomes “We’ll never be silent again”), target opponents (the New York Times, President Reagan, Cardinal O’Connor), define positions (“All people with AIDS are innocent’), propose actions (“Boycott Burroughs Wellcome”) . . . In the end when the final product is wheatpasted around the city, carried on protest placards, and worn on T-shirts, our politics, and our cohesion around those politics, be- come visible to us, and to those who will potentially join us.

One of the most prolific of all the ACT UP art collectives, and the one responsible for much of the protest ephemera, was Gran Fury.

This Is to Enrage You

“We wanted to point out that the idea of the isolated cultural producer, the lonely artist in the studio, was one that at a time of crisis for us did not quite work, did not reflect the necessities or the possibilities of what collective action could do.” – Gran Fury

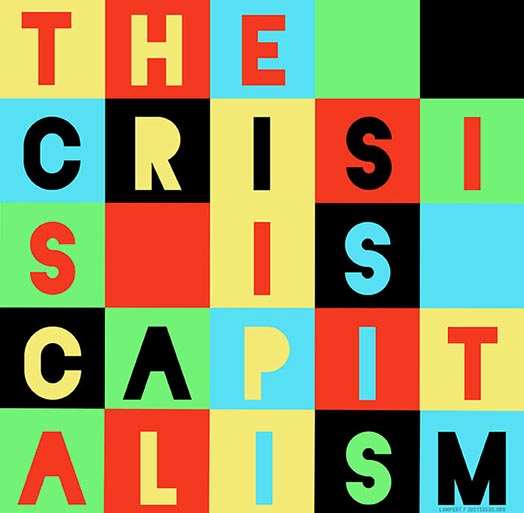

Gran Fury, a ten-to-twelve-person activist art collective within ACT UP/NYC, was formed in January 1988 and created myriad projects, including posters, stickers, flyers, bill- boards, bus ads, art installations, fake newspapers, and other forms of creative resistance. Gran Fury specialized in bold graphics and simple slogans—images were produced for actions, often the night before, and images were constantly re- purposed.

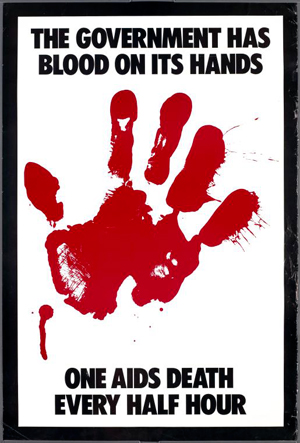

The Government Has Blood on Its Hands followed this rubric. The poster was initially created for an ACT UP demonstration on July 28, 1988, against the New York City Department of Health (DOC) and NYC health commissioner Stephen Joseph. Joseph had enraged activists by stating that only 50,000 NYC residents had AIDS (instead of the more accurate number of 200,000) to justify the city’s minimal commitment to care services. The poster itself featured a blood-red handprint with text that read YOU’VE GOT BLOOD ON YOUR HANDS STEPHEN JOSEPH. THE CUTS IN AIDS NUMBERS IS A LETHAL LIE. An alternate version of the poster was aimed at Mayor Ed Koch for his failure to seriously address the AIDS crisis. It read NYC AIDS CARE DOESN’T EXIST, which was a bitter reality. Mayor Koch had provided a measly $25,000 in funding for AIDS research and patient care in 1983, compared to the $1 million that Mayor Dianne Feinstein had committed in San Francisco, a figure that was still too low. To address the failure of politicians in NYC, Gran Fury wheat-pasted the poster in the streets and “crews of ACT UP members went about with buckets of red paint, into which they dipped their latex-glove-covered hands to imprint bloody palm prints all over the city.”

Other actions were just as confrontational. During the second Wall Street action on March 24, 1988, Gran Fury photocopied thousands of $10, $20, $50, and $100 bills onto green paper and scattered them all over the streets, causing traffic to come to a standstill. There were 111 ACT UP activists arrested while passersby and Wall Street brokers were invited to collect the fake bills; messages on the back of the bills read, among other things, White Heterosexual Men Can’t Get AIDS . . . Don’t Bank On It” and “Fuck Your Profiteering: People Are Dying While You Play Business.” Gran Fury member Loring McAlpin reflected on the simplicity of the technique: “If you’re angry enough and have a Xerox machine and five or six friends who feel the same way, you’d be surprised how far you can go with that.”

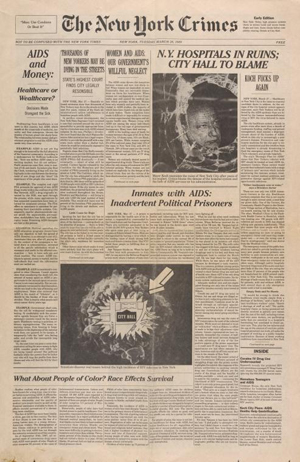

Some Gran Fury actions took more time and resources to create. ACT UP/NYC consistently held the New York Times responsible for its abysmal reporting on the AIDS epidemic, consistently underestimating the scale of the crisis. The June 29, 1989, editorial “Why Make AIDS Worse Than It Is?” became the last straw. It argued that the virus was leveling off and was confined to “special risk groups,” saying in not-so-coded language that straight readers could relax while gay men and intravenous drug users died. In response, ACT UP demonstrated in front of New York Times editor Arthur “Punch” Sulzberger’s Fifth Avenue home in late July. Body outlines were painted all over the streets, fact sheets were handed out throughout the neighborhood, and a large demonstration took place. The Times never felt compelled to cover it.

To further address the lackluster reporting, Gran Fury printed thousands of copies of their own version of a fake newspaper called the New York Crimes that included stories by ACT UP members and graphics by Gran Fury. The four-page paper mimicked the look of the Times and was placed in newspaper boxes during a late-night action.

Activists fanned out throughout the city at four in the morning, opened Times newspaper boxes, and wrapped each paper with the new-and-improved front-page section. Included in the Crimes was a full-page graphic of a laboratory scene with a quote by Patrick Gage of the Hoffman-La Roche pharmaceutical company: “One million [people with AIDS] isn’t a market that’s exciting. Sure it’s growing, but it’s not asthma.” Below the egregious quote, on the bottom of the image, Gran Fury simply added the commentary: “THIS IS TO ENRAGE YOU.”

As a small collective, Gran Fury members would meet at the end of ACT UP meetings on Monday nights and discuss project ideas. Anyone in ACT UP/NYC was welcome to take part. By their second year, the group be- came closed. A good working nucleus had been formed and it became too difficult to work with noncommitted people who would come and go. By their second year, Gran Fury began meeting once a week at someone’s apartment or studio. Here, they would debate ideas for images and actions, alter them, reject them, choose projects to take to the larger ACT UP meetings for discussions, and sometimes choose to do projects autonomously on their own terms. None of the artists in Gran Fury were paid, nothing was copyrighted, projects were credited to the collective’s name, and nothing was sold on the art market. Everything that Gran Fury created was for the AIDS movement.

Gran Fury’s drift toward more autonomous projects grew out of the frustration of seeing their finished ideas debated and overanalyzed by three hundred–plus people at the Monday-night meetings. Michael Nesline reflects:

[Gran Fury] didn’t want to have to listen to ACT UP’s—why is it blue? Why shouldn’t it be green? We don’t want to have to listen to a conversation for 45 minutes about which is better, blue or green. We’ve already had that discussion, and we’ve decided it’s blue, and we’re not going to have the discussion again. And, we don’t really need to justify it, too. If you don’t like it, you don’t like it. So, tell you what—we’ll just do what we’re going to do, and if ACT UP is doing something, and we feel like piggy-backing onto that, we’ll piggy back onto that. And, if we feel like doing something on our own, we’ll do it on our own.

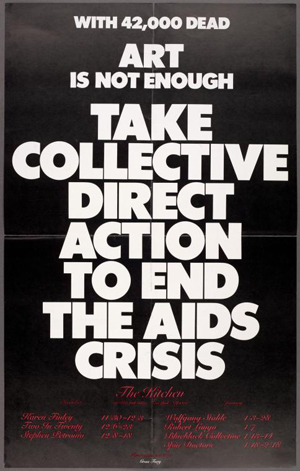

The poster With 42,000 Dead, Art Is Not Enough, Take Collective Direct Action to End the AIDS Crisis represented work aimed at an art audience. The text-based image served as an advertisement for the NYC performance art space The Kitchen and communicated the need for both art and direct action to confront the AIDS crisis.

Gran Fury clearly understood the dire need for art and cultural activism, but they equally understood the limitations of the medium. Art was not enough if it was isolated within the art world and under- stood primarily as a commercial object to exhibit and sell. Gran Fury knew that they could benefit from the contemporary art world. As Gran Fury evolved, they began to tap into artist grants to fund their projects and museum shows to gain more exposure for the issue. Nesline viewed this as a win-win situation:

Here’s this little Cinderella group [Gran Fury] that makes art that can’t be sold, because it doesn’t exist, and they’ll give us money so that we can produce our art projects, which are actions, and the art world can feel really good about themselves, because they’ve now contributed to the AIDS crisis—to ending the AIDS crisis—and we can feel really good that we’ve taken their money. So, we’ve used them, and we’re not going to give them anything in return, because there’s not going to be any art product at the end of it that can be re-sold and could accumulate in value. So, our status as Cinderella was preserved.

In short, Gran Fury navigated both the activist and the contemporary art world. Their message was aimed at all.

http://peoplesarthistoryus.org/

http://justseeds.org/nicolas_lampert/03pahbook.html

More on ACT UP:

Gran Fury images at NYPL Digital Gallery

ACT UP Oral History Project

How to Survive A Plague – documentary Film