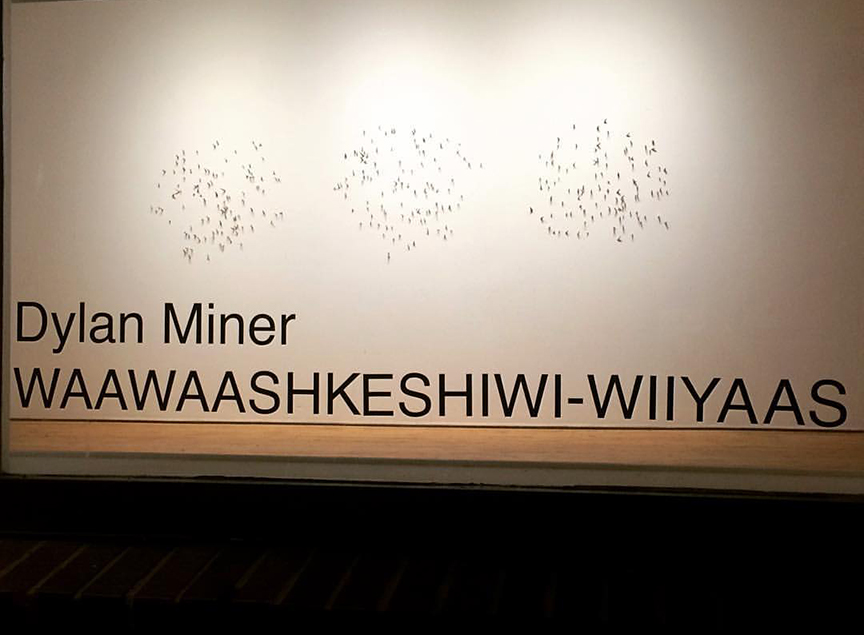

For my first entry in Aniibiishaaboo miinawaa Makade-mshkikiwaaboo – Tea and Coffee, I want to reflect on my exhibition that is currently on view at Artspace in Nogojiwanong (place at the end of the rapids, also known as Peterborough, Ontario, Canada). You can read the brief gallery guide to the exhibition here.

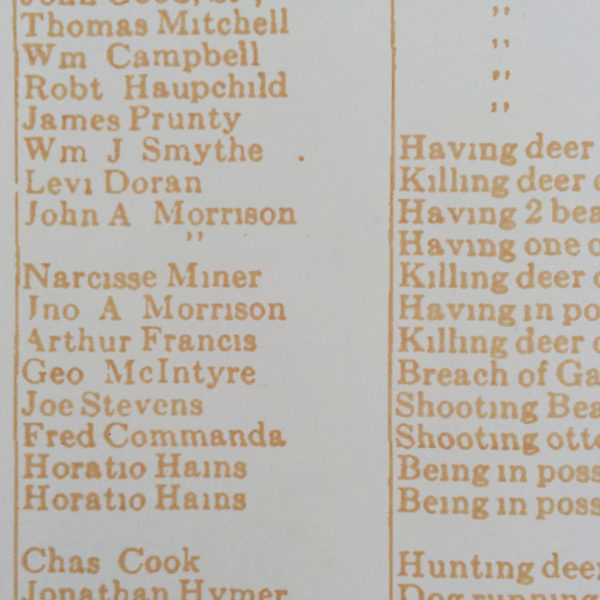

A few years ago, I discovered a document that recorded my grandfather’s grandfather – who I would call my gichi-aanikoobijigan – Narcisse Miner was convicted in 1906 for hunting a deer out of season. I later had a conversation about this event with my great-great-auntie, who remembered stories of this incident. Narcisse’s conviction happened on his trapline in Ontario’s Georgian Bay region near Lake Huron. Narcisse’s mother was Red River Métis and his family had worked for many generations for the Hudsons’ Bay Company. They had lived, worked, and traveled across what many call the Métis Nation Homeland, on both sides of today’s US-Canada border. In fact, Nascisse’s grandfather had fought against the Americans during the War of 1812 and was among a group of Métis, Anishinaabeg, and voyageurs who were forced from Bootaagani-minis (Drummond Island) when it became part of the United States.

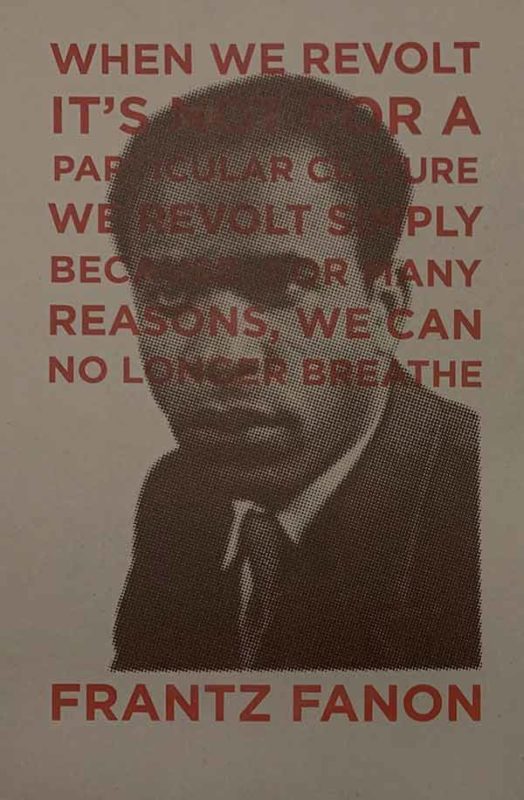

Much of my recent work has been thinking about Indigenous resistance to ongoing colonial histories and policies, including familial stories and histories. I am particularly interested in the ways that history and futurity link back up in undeniable ways. I decided to work on this project while reflecting on the Anishinaabemowin word for an ancestor – aanikoobijigan – which is also the word for descendant. The word for great-grandmother becomes the same as the word for great-granddaughter. For each subsequent generation out from your great-grandmother/father/daughter/son, moving in multiple directions, the base-word aanikoobijigan is appended with the prefix gichi, meaning: big, great, very, or quite. By working on a project about my grandfather’s grandfather, I am also making work about my granddaughter’s granddaughter. In my mind, this is an irreducible component of my practice.

For Waawaakeshiwi-wiiyaas, I wanted to think about subsistence hunting and reflect upon the colonial violence inflicted on Indigenous communities when their/our practices are delimited by colonial jurisprudence and legislation. The settler-colonial violence of being unable to harvest your own food, as was the case of my gichi-aanikoobijigan, is integral to the way that colonial systems work and reproduce themselves. By making artwork about these things – especially art intended for the gallery and not for the street – I do not naively assume that my practice will undermine the colonial or capitalist system. However, by engaging with this history (and of course, future) and integrating ancestral knowledge (which is simultaneously descendent knowledge) into the making of this project, I have moved my own place in the world from one that singularly works to dismantle systems of oppression to one where I imagine – acting in all historical directions – different worlds (to borrow from the Zapatistas). As a father of two teenage daughters, I am interested in activist ways of being that do not only challenge power, but struggle to live otherwise. Of course, I understand my own complicity in systems of power and privilege. Having temporally looked backwards, forwards, sideways, and otherways, I understand that these were/are concerns that my gichi-aanikoobijigan (grand-parents’ grandparents and grandchildren’s grandchildren) were dealing with and will be dealing with.

In conversations with curator Jon Lockyer, I decided to develop a project around an incident when my grandfather’s grandfather was convicted for hunting a deer. As part of this project, I will return to the Georgian Bay next fall to attempt to harvest a deer – and if successful feast on the deer in a community celebration at the gallery. The project is organized in three phases, commencing with the initial phase, which is currently on view at Artspace.

The current exhibition includes two primary components in two separate galleries. In the first gallery, which is quite large, I have installed thirteen works on gallery walls, singularly consisting of the tips of deer antlers. Each work, which have circular forms, are starmaps based on the thirteen moons of the year. Within each map, those who can interpret them at least, will notice various constellations, both Indigenous and Western. For me, each map focuses on a single Anishinaabe constellation, located in clusters of other stars. To help make these works legible, next year, I will create an artists’ book that will help clarify these works for those unaware of Indigenous sky knowledge. Of course, this will also help me work through these ideas, as well.

Personally, the antler tips and constellations demarcate time and space, with each map consisting of 110 antlers. These constellations, in turn, recall particular sections of the sky and 110 stars within it. These starmaps are about the relationship between the stars and the aanikoobijigan and us. They are about the passing of time – in various directions. They are about the interconnectedness of various beings – including all of us – and manidoog (spirits). Since Narcisse was convicted 110 years ago, the thirteen constellations with 110 stars in each starmap evoke the number of years since this particular moment of settler-colonial and state violence. Using aanikoobijigan as a conceptual point of emergence and metaphor, these works also prefigure things 110 years in the future.

In the back gallery, I have created a limited edition serigraph – printed in animal blood – of Narcisse’ ‘return of conviction,’ which I found in Ontario’s legislative journal. The use of blood could be read many ways, and I appreciate this ambiguity. Materially, this is a new exploration, and I spoke with master-screenprinter and collective-mate Jesús Barraza on how to actually print in blood. To make the blood printable, I mixed it with an acrylic base for printing effectiveness. These 110 prints are hung in a matrix on the northern and southern walls. The eastern wall, which points towards the rising sun and place of emergence, includes a single framed print that is surrounded by two shrouded deer heads and two commercial trail cameras that are produced for sport hunters to track deer when they are not themselves in the bush. Here, I am thinking about the ways that the nation-state and settler-colonial technologies engage in surveillance against Indigenous communities and non-human beings, as well. The burial shrouds offer the deer a sense of postmortem respect that challenge the trophy-like specter of European and settler-North American wall mounts. In the center of the room, a single commercial picnic table, wrapped in a Hudsons’ Bay blanket, becomes a space for feasting and non-commercial social exchange. The gallery becomes social and gathering space.

In early June, I will be heading back to Regina, Saskatchewan, where I am in residence at the Mackenzie Art Gallery. In Regina, I am working with four indigenous artists – Stacey Fayant, Katherine Boyer, Eagleclaw Thom, and Keith Bird – who are, in turn, working with urban youth to build lowrider bicycles that circulate around Treaty Four. I will connect back up with everyone about that project in a few weeks. Baamaa pii miinawaa.

Fascinating stuff. Curious to hear how you’ve learned about the Anishinaabe constellations, and what they represent.

Very much interested in the constellations and getting my hands on whatever you publish about it!