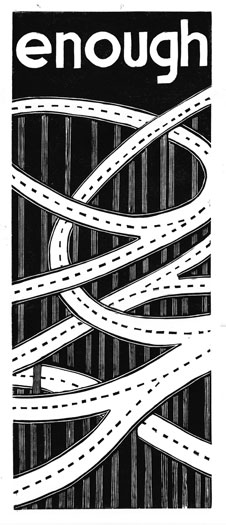

It’s been hard to know to make graphics and art that responds to the terrible and evolving situation that we are in. Our realities shift so quickly that an idea you might have one day can seem trite or irrelevant the next. It’s been further compounded for me as I’ve been working as a nurse throughout this. I want to make things that reflect the reality of our collective situation and dreams, images that may be useful and relevant; and images that draw on my experience of working with the sick and the dying. These aspirations, along with the generalized anxiety of living through all of this, can be stifling—in that I aspire to make some type of grand-theory-as-encompassed-in-an-image-piece or I skip that idea entirely and just try to produce a simple message with discrete edges. One is impossible and the other isn’t fulfilling. There is a desire to feel useful and that can be hard to achieve.

For the last three weeks I have been working in our ad hoc biological isolation critical care unit, with covid patients. Prior to this I was working in our regular ICU, with patients without covid, and some with suspected covid—sometimes with protective equipment, sometimes without. We’ve had a string of young patients who have gone into sudden respiratory collapse who have tested negative, which makes you wonder what else is going on out there and/or makes you question the veracity of testing.

If you’ve been paying attention at all over the last two months these are all things that you probably know. But here’s something you don’t know: A month ago I was taking care of an older gentleman who had an anoxic brain injury after overdosing*. He was not a covid patient. He had a full chest tattoo of the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist iconography written on his body. He was violent and sexually aggressive towards staff and due to his injury he didn’t have full control of his body. He had diarrhea, and while I was cleaning him he was threatening physical and sexual violence on me. Not one of these things on their own is unusual in this job—but this was like a perfect storm of unpleasantness. It was mid-March, early in the covid days, I was receiving lots of support from friends, housemates, and from the world, really. When I got home I thought about how hard it was to maintain patience, care, and attentiveness to people sometimes. How the hard part of this job could come from any direction. I wasn’t sure what it meant to be called a hero in this context. Almost immediately after that I was assigned to work in the newly opened covid ICU, and, selfishly, it was a bit of a relief to have patients so sick that they couldn’t talk or threaten (and FYI all of the covid patients we have seem like nice people, probably not nazis).

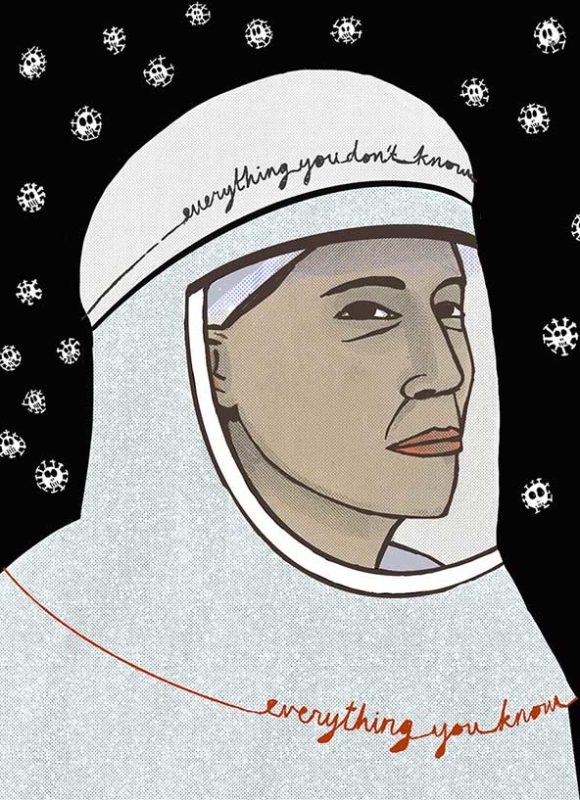

If you work in critical care, you are accustomed to a certain amount of alienation from your patients—they are reduced to simple sick bodies that need care, often comatose or deeply sedated. You usually wear gloves to touch them, you might wear a mask or gown in the room depending on infection. Airborne isolation is unusual, reserved for infectious states that are pretty rare. But these days we are not breezing in and out of rooms to do what we need to do, we are suiting up (‘donning’) to travel into rooms, trying to ‘cluster care’, and then decontaminating to leave (‘doffing’). Several of our patients are on life support systems that require frequent attention (ECMO, dialysis), and these involve staying in rooms for long periods of time. Nursing is a very social job, but as we are conserving PPE, it can be hard to get help at times. We are reliant on systems we haven’t had to think about much, like the effectiveness of the filters in our respirators, the lack of negative pressure rooms in our hospital, and all of the other questions that have been ongoing through out this pandemic. So I’ve been drawing, trying to make something that felt resonant with this current reality: of being a person in this situation, the strangeness and thin safety of PPE, the unknowing unknowingness of coronavirus transmission.

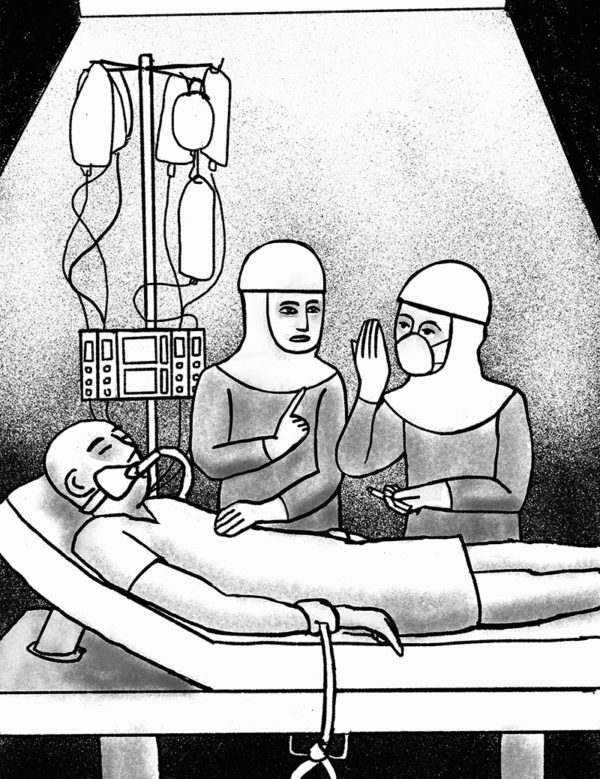

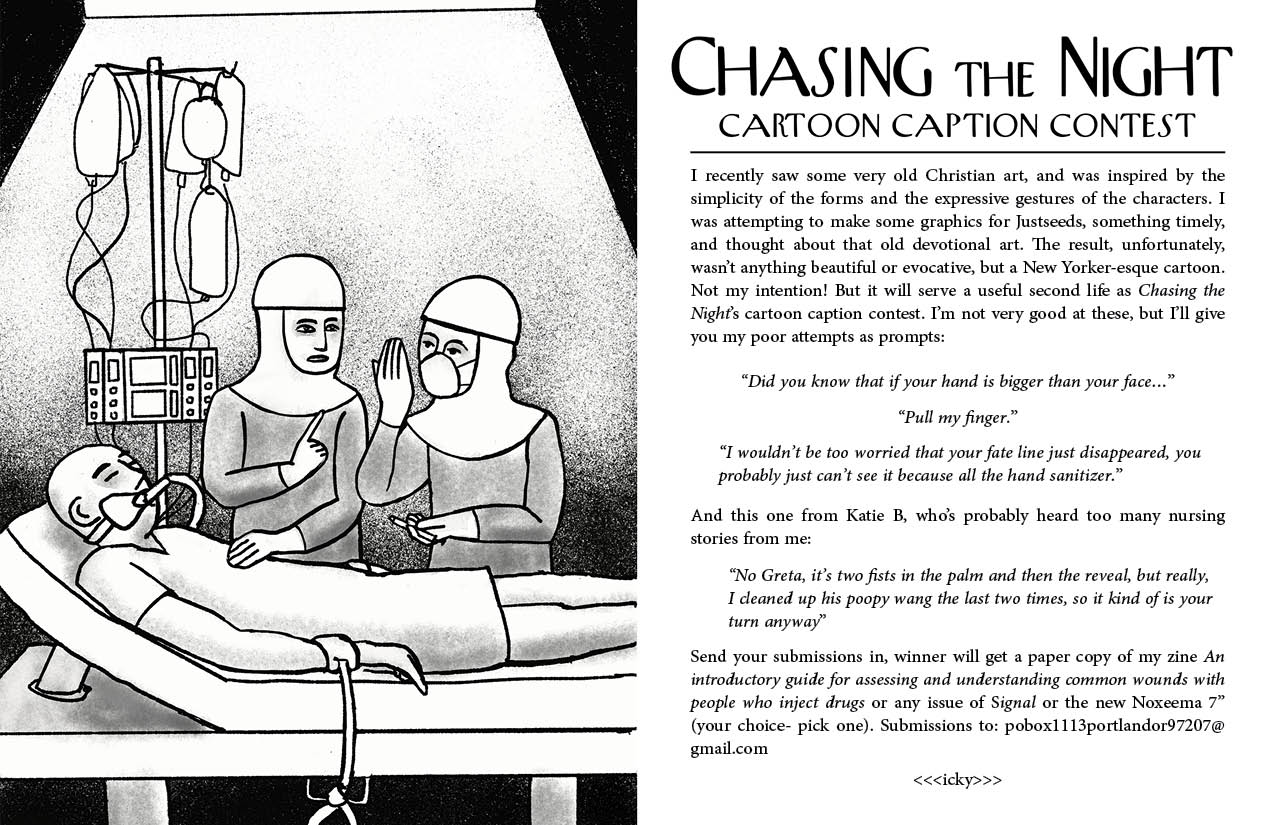

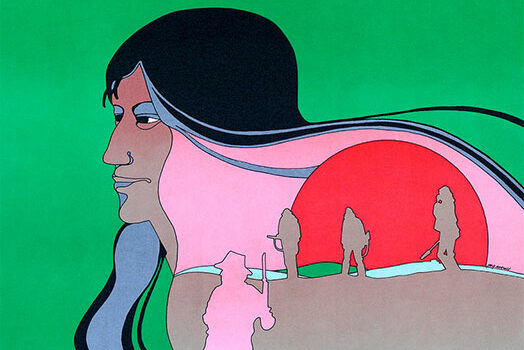

In doing this I found that I have fallen back on some tropes that I have been opposed to: the nurse as saint, the nurse as holy, the nurse as pure. Is it true there are no atheists in foxholes?** Maybe, but I’ve also been trying to avoid war metaphors, so forget that. I came upon the religious vibe in these drawings by chance. After torturing myself over my first drawing (at the top of the page) I saw a crusades-era devotional painting and thought of how the soldiers in the picture looked like they were wearing PPE (which in a literal sense, they were), and admired the simple expressiveness of the image. I made a drawing exploring that influence, and perhaps using too many gadgets on a tablet with new drawing software. The result (above), when I stepped back, looked like a comic from the New Yorker, which was a disappointing but also unexpectedly funny result. At the time my friend Erin Yanke was soliciting work for her zine Chasing the Night, so that ended up as a caption contest for that (with direct design references to the New Yorker).

The third drawing (below) I did a couple of days ago. Before I started I thought to myself, “Let’s do this again. Just start fresh, draw a face, get loose, and see where it goes.” The face with the respiratory PPE, once again, looked very religious—this time with a more 1970s Catholic vibe—an aesthetic I can get with. The PPE that we use are actually called PAPR shrouds, and in the drawing it looked very much like a saintly shroud. I then thought to add the corona halo. Are we baptized through our willingness to work during this? Sanctified by exposure? Maybe… but as medical workers we are privileged to expect protection— what about bus drivers, postal workers, grocery store clerks? Making these has been a process, bringing up many questions and few answers which seems appropriate for the way we are living.

*details changed to protect the innocent my nursing license, but outline remains the same

**My dad is/was an atheist and was in a foxhole, so I know this not to be true, actually

Thank you for your powerful words. Take good care.

We are thinking of you! Thanks for your beautiful work and sharing your experiences.