A few years ago, I desired to learn to speak to plants and learn their language. Although I had been raised primarily in the woods in Michigan’s Thumb, I didn’t have the language to listen to the plants. I could not identify more than a few well-known varieties of trees or flowers or berries. At some point in time, the Indigenous plant-based knowledge that my grandfather’s grandmother was known to have, disappeared from my family. As an artist, I have the privilege to work in a way where my projects emerge from a desire to address certain issues or questions or – as happens most frequently – there is something I need to learn (not for myself, but rather in relationship to community). In this particular case, I wanted to learn to engage in conversation with plants. As such, I come to my practice as an artist, and especially in this project, as one of decolonial learning and sharing.

Much in the same way that I began to work with bikes and youth from a collective desire to increase our shared knowledge – while sharing that with others – Michif-Michin (the people, the medicine), as I call this project, allows me the space to spend time in the woods, and on the prairies, and lakes and swamps, and anywhere else where plants grow. It is about personal and collective healing. It means that I harvest berries between my activities with my daughters and escape into the woods when transferring trains in places I’d never been before. It means awakening before dawn to drive hours to meet at elder for harvesting. It means smelling like smoke and sugar during maple sugaring season. It means organizing workshops with elders who hold knowledge about manoomin (wild rice). It means traveling and visiting. It means lots of things. Michif-Michin (the people, the medicine) is about being in the world in a way that places value on relationships and not on things.

But, I am a novice and I do not know much about plants. I am neither an ethnobotanist, not an expert. I am a learner at best. I am an artist and a community-member that has only recently begun to learn to listen to the plants and, at times, have conversations with them. In this process, I’ve learned how little I know and how little I can ever know. I am consistently reminded how many plants I cannot identify or understand, even those growing near my home.

As I sit here writing this brief essay – having just spent time in unceded Coast Salish Territory – I cannot escape the memories of harvesting on the land: the smell and sound of harvesting birch bark in Michigan’s upper peninsula or the feeling of wet moss on my knees as I pick mossberries and Labrador tea in the far north. I recall my own shyness and awkwardness, both with plants, but also with humans. By connecting with my food and with the plants, I have become more human. I have become less awkward and more alive. Just as we must build trust with other humans – and with animal-beings – so too must we establish a rapport with the plants. While I acknowledge the important information that I have learned from other humans in the process of this project – from writings in books and on the internet; from digital conversation through email and on Facebook; through conversations over mshkiki-waaboo or while in the bush – I like to think about Michif-Michin (the people, the medicine) as a collaboration with the plants themselves. It isn’t just human knowledge, but plant-based ways of knowing. I wonder what it would mean if we started to think about the various plants as co-collaborators. What would it mean to collaborate with them? What does any of this mean?

I am presently heading home from an extended visit in Vancouver, a city that sits on unceded Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh lands. When I get back to Michigan, it will be time to harvest birchbark. I like the fact that much of my life is dictated my the seasons and the plants and the natural world. As I boarded the plane, I noticed a message on my cellphone from the elder with whom I harvest bark. I’m hoping he is checking in about dates to harvest wiigwaas. I’ve been in Vancouver working on a project for Gallery Gachet, an artist-run centre located in the Downtown Eastside. Gachet is an important space that has a commitment to the neighborhood, as well as a commitment to using the arts to address mental health. I am excited to be working in the Downtown Eastside, as well as with Gachet and the community members with whom they’ve been connecting me.

I hope to write a few posts while I work on this project – a project that in many ways has simply become my life. If you follow me on Facebook or Instagram, you will see I was actively harvesting medicines while in Vancouver. While there, I spoke with cedar and yarrow and fireweed and horsetail and salmonberry and many others. When I arrived in Vancouver, I had developed a chest cold and had a throbbing headache. One of the first things I did was harvest horsetail, boil it and breathe in the vapors. I also made some cedar tea and engaged in ceremony. Moreover, I spent time meeting with elders and community members, sharing food and stories and time.

Last week, T’uy’tanat (Cease Wyss) conducted a beautiful plant walk in Stanley Park, which was organized by Gallery Gachet as part of my project here. Nearly fifty people attended. The large number of people attending is indicative of the need for many of us – Indigenous, settler, and arrivant alike – to learn to speak with the plants. Cease is doing important decolonial work. I also traveled with Anne Riley and Cecily Nicholson to the University of British Columbia, where Anne shared stories and knowledge about Indigenous community gardens. Cree elder Robert Bonner organized ceremonial activities and gifted me some sage. I shared a meal with Rodrigo Hernández and members of his collective, discussing Indigenous medicines and anticolonial struggles in México. I ate dosas with artists Carmen Papalia and curator Kristin Lantz. Community members from the Downtown Eastside shared songs and bannock and tea. We shared stories in the gallery and made new relationships. I shared dinners and walks and spoke with the plants. I believe that art has the possibility to be many things and that many things can use the language and infrastructure of art. I imagine a world where art is the way in which we build non-colonial and non-capitalist modes of being in the world. This is but one attempt.

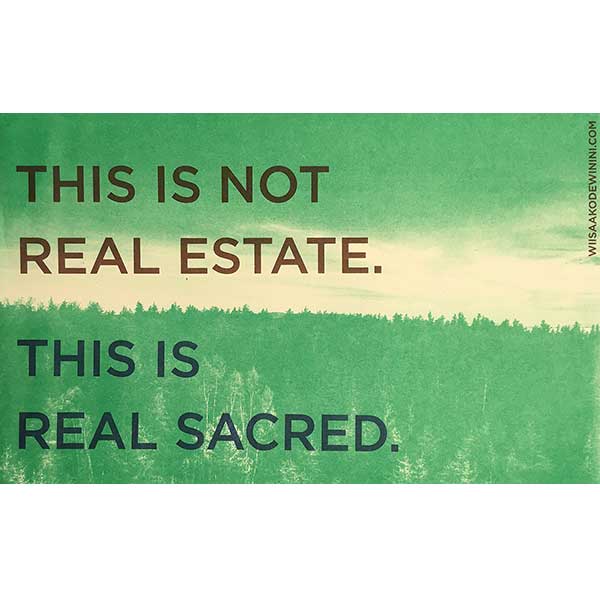

Activist art has the ability to resist and challenge repressive and colonial and capitalist institutions and structures. I think this kind of work is needed. However, I also believe that we need to remember that other ways of being in the world are still possible. Many people are still living them and that since time-immemorial, many communities have been practicing ways of being that are beautiful and fulfilling and non-colonial. I hope that, if nothing else, I can use my privilege as an artist to practice some of these ways, while imagining new ones. I think the plants can help us in this regard.

[…] more about Dylan’s thoughts on plants in Vancouver on Justseeds, an artist collective focused on social, environmental and political engagement. The […]