Throughout my life, I have known plenty of folks who have used roadkill for a variety of purposes. In addition to dumpster diving baked goods or produce, many of the freegan folks I knew in my twenties would eat roadkill, of course, only if fresh enough. This winter, when speaking with an elder in the urban Indigenous community where I live, he told me about the times when he and others were leaders of the Lansing Indian Center. They would get phonecalls from various people – community-members, as well as from governmental employees – when someone hit and killedwaawaashkeshiwag (deer) with their automobiles. Community-members would process the meat and then gift it to others in the community or use it in community feasts. Ethically, I love the idea of eating roadkill and honoring the spirit of those waawaashkeshiwag killed by cars. However, given that my mother has innumerable stories of death from situations potentially must less harmful, I have never eaten roadkill – in any form. Thanks mom, I guess.

While I might not have eaten roadkill, I do commonly use parts from those dead animals that litter the highway and back country roads. I would say that the countless animals that line the road, wherever I travel, are the structural detritus of automobility. While we may feel bad when we accidentally kill animals with our autos, it seems that our guilt is only momentarily. Personally, I can still recall the time I ran over a rabbit as a teenager or, more recently, hit a fox when driving to my grandmother’s home on Christmas Eve. Needless to say, I cherish those times when I stop along the side of highways and county roads to honor a deceased animal and to harvest parts that I can use in my own cultural practice or – better yet – give away to others. Just this past weekend, as part of my mentoring Indigenous students at Graduate Horizons, I gifted gaawayag (porcupine quills) that I recently harvested along the road near Cadillac, Michigan to those students I was mentoring. For me, this helped establish deeper social relationships with one another and with the land.

About a week ago, I was driving home from visiting family and spending time in Northern Michigan. Although driving alone, my eldest daughter, Reina, was traveling with a friend. They were about fifteen minutes ahead of me. When my daughter noticed the recently deceased body of a porcupine on the side of the road, she immediately texted me – she was the passenger – and let me know its location. When I came across the gaag (porcupine), I quickly pulled over. After offering some semaa and song, I began to remove quills from the porcupine. I filled my wiigwaas-makak (birchbark berrying basket) about one-third of the way, leaving plenty of quills for those who may have stopped by after me.

As my daughters and partner know all too well, it is common for me to harvest road kill. It connects with the land and with those other being who are traveling similar pathways. A few summers ago, I picked up a bird that was infested with insects, which began to fly into the hair of everyone in the car. In retrospect, it was quote a hilarious situation, but at the time, there was little laughter. At that moment, I made a commitment to my family that I would only stop for roadkill if I am traveling alone and, more importantly, if I was driving my truck and could place the animals or parts in the bed. When my daughter texted me, I knew that even if she wasn’t stopping to harvest the quills herself, she was nonetheless attentive to the animals and to her environment. This is something we should all be doing.

Where I live in East Lansing, we do not generally have porcupines. Up North, as people say around here, you’ll see lots of porcupine, both living and dead. If you know Michigan’s ecology, you realize that the northwoods start somewhere around Clare – just south of the 44th parallel. US 10 is my somewhat fictive border between Down State and Up North. This demarcation-line also helps me know when I should become more attentive to possible porcupine roadkill. While you may see porcupines (or porcupine roadkill) south of this point, I feel it is helpful to know where I should become more attentive. Wild turkeys, however, can seemingly be found everywhere.

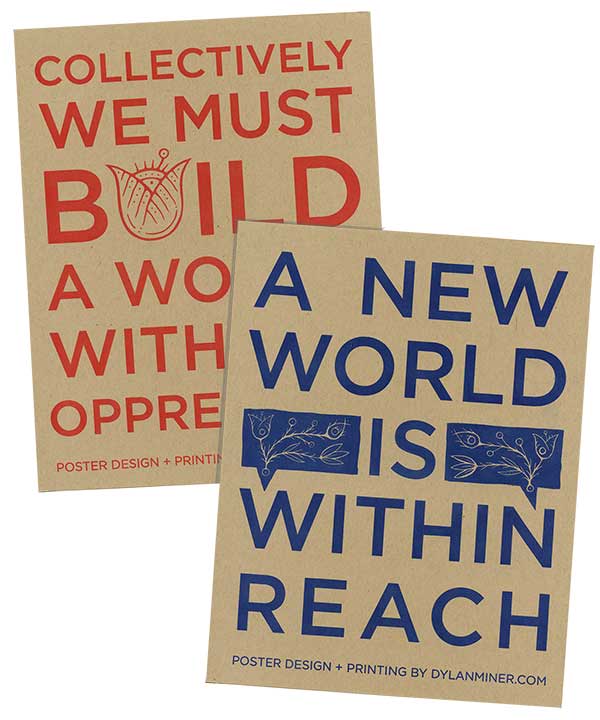

Porcupine quills are a wonderful material for artmaking. Many Indigenous nations have traditions of using quills within their art and cultural practices. While wuillwork pre-dates beadwork, it is still actively practiced throughout Turtle Island. The above image is a beautiful example of Métis quillwork in the collection of the Minnesota Historical Society. Thanks Ben Gessner for showing this important collection. Quillwork, as this artform is known, has an especially long tradition across the woodlands, plains, and subarctic. I’ve viewed wonderful archival collections of quillwork in the National Museum of the American Indian, as well as in the Minnesota Historical Society and other museums and personal collections. Quills can be used on bucksin or on birchbark and when dyed allow for beautiful and multi-colored imagery to be created. There are a variety of ways to attach the quills to the backing. Historically, quills were dyed with natural dyes, which many artist still do today. However, it is also common for quillworkers to use commercial dyes like Rit to get vibrant colors, such as quills I dyed below).

I am definitely not a skilled quillworker, but the more I learn about plants and plant-knowledge, the more I can also begin to incorporate this into my everyday place in the world. Miigwetch miinwaa baamaa pii.

I’m looking to purchase a whole animal to do quill earrings with. Please let me know if you can direct me n the right direction