I was two years old and five thousand miles away in Ecuador when Los Siete de la Raza were railroaded for the shooting death of a cop in San Francisco, in front of a house a block away from where I now live. The reverberations of that incident, and the political awakening of the San Francisco Mission Latinx community, shaped my own political development many years later.

I think I first heard of Los Siete from community organizer Eric Quezada, when I was finding my own political road with the Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition (MAC), and trying to figure out how my activism and art skills met. Eric spoke of Los Siete as the left pole of Mission District politics that has continued to define the neighborhood decades later, a radical alternative to the nonprofit-driven activism that we were all involved in, in one way or another. Through MAC, I met the San Francisco Print Collective, who, Atelier Populaire-style, provided the visual aesthetics of MAC’s activism, blanketing the walls of the Mission with wheatpasted posters, and it was through the Print Collective that I found a direction to my own artmaking. Somewhere in those same years, organizing a Latin@s Against the War contingent in the leadup to the invasion of Iraq, Betita Martinez introduced me to veteran artist Yolanda Lopez, and I heard her own story of finding her artistic path as a core member of the Los Siete organization in 1969.

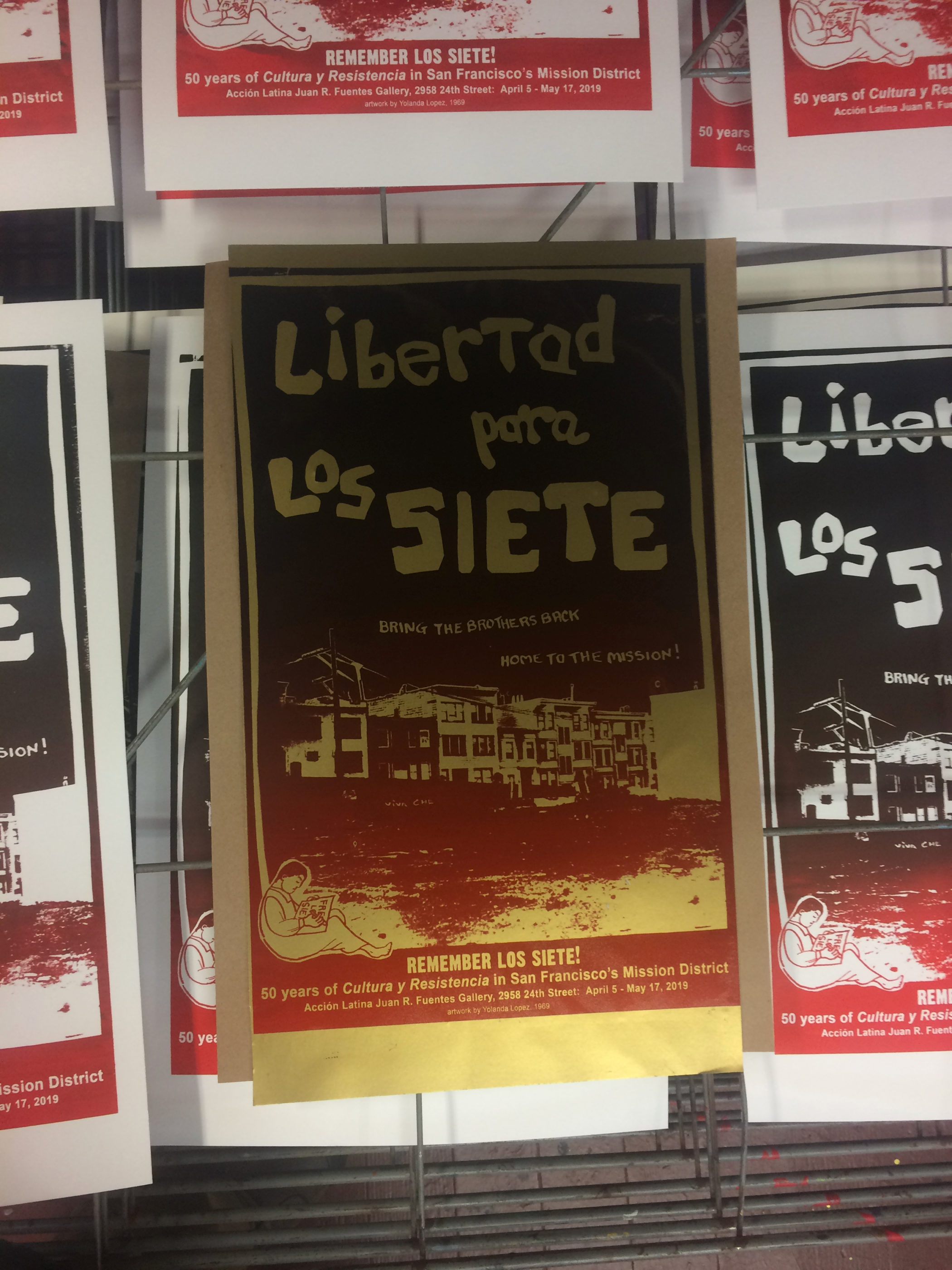

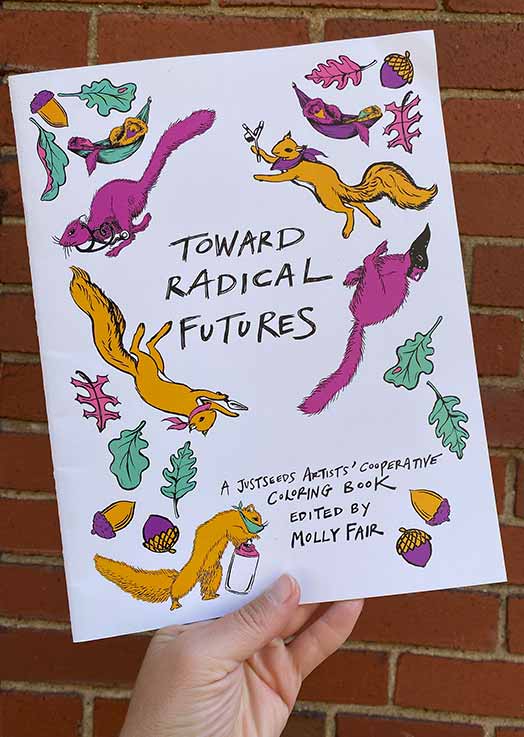

One of my first projects after joining the Justseeds Cooperative was to create a bilingual Celebrate People’s History poster telling the story of Los Siete. But it’s been a dream for the last ten years to create a space to not just remember, but to reflect on and engage with that history. This year, on the 50th Anniversary of the incident that sparked Los Siete de la Raza, I had the honor to curate an exhibit on Los Siete with Yolanda Lopez at Acción Latina’s Juan R. Fuentes Gallery in the Mission District.

Los Siete is a bit of forgotten history, or perhaps it’s erased history: too radical, with its close association with the Black Panther Party, hints of Mao’s little red book, and revolutionary riffs about “Third World Liberation” and “Serving the People,” to fit neatly, even within our own Latinx histories, of the trajectory from zoot suit riots to farmworker pilgrimages to Sonya Sotomayor. And it’s also human and messy, not always heroic, a story of seven young Central American immigrants already characterized by the SF Chronicle as “thugs” and “hoodlums” even before the incident happened, a view held too by the more mainstream “leaders” in the community. Some of the brothers went on to become professors and others ended up dying in prison. While much of the exhibit was about the organization that grew up around them, Yolanda made sure we remembered each of their names: Tony Martinez, Mario Martinez, Pinky Lescallet, Bebe Melendez, Jose Rios, Nelson Rodriguez, and Gio Lopez. In her multi-media performance at nearby Brava Theater, “Remember Los Siete,” filmmaker Vero Majano retold each of their stories and how it impacted her growing up in the streets of the Mission.

Two of the brothers stopped by the exhibit, appreciative that we remembered them and their struggle fifty years later. They had not talked about Los Siete for years. They shared with the gallery staff how their histories followed them, costing them jobs, and even now, still wanting to maintain a distance. It’s easy for some to forget the trauma that the experience left on the seven young men. They had to live with it the rest of their lives: “It was a terrible day,” one said.

One of the things that struck me was how the seven brothers stuck together through the trial, and how the community understood that this attack on seven young men was an attack on the community itself. That we all had to stick together. It reminds me of the slogan used by prison activists today, All of us or None.

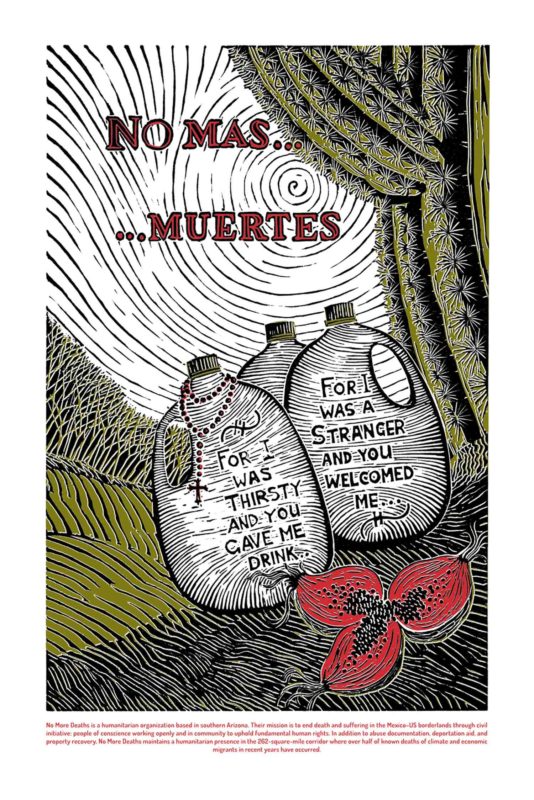

As an activist, much of my interest was in tracing the echoes of 1969 to our own day, the issues Los Siete were dealing with, from development and gentrification (before that word existed) and the internal colonization of our barrios and neighborhoods, to today’s situation in the Mission District – the capitalist subtext to the more visible targeting of black and brown youth.

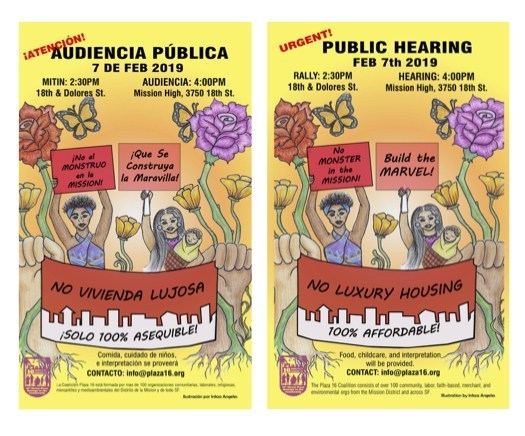

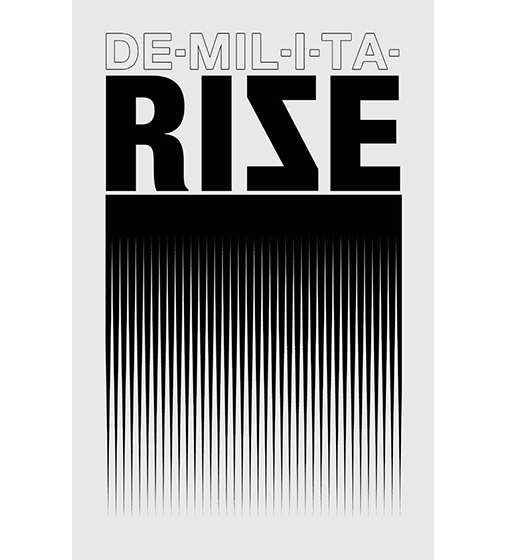

At a gallery discussion on Fifty Years of Gentrification, from Los Siete to Today, Galería de la Raza director Ani Rivera recalled the recent eviction of the venerated community institution on 24th Street. “They want us to just pick up our tiliches and go. But we have this ancestral memory of place.” Galería de la Raza’s fight is “not for another fifty years, but for seven generations.” María Zamudio of the Plaza 16 Coalition reminded us that these are all just “different iterations of the same pattern.” Today’s response draws from our own radical histories of imagining a different future. What’s important, Maria says, is realizing that “this isn’t inevitable. They want us to think, ‘Evictions happen. Isn’t it all over? Así son las cosas. Ya se acabó.’” But it’s not over, not when there’s still a community fighting to stay. “There could be one grandma left in the Mission. I’ll fight for her.” At the root of these struggles, PODER organizer Jacquie Gutierrez reminded us, is “the centrality of land.” Losing that is not inevitable. “La Dieciseis. La Veinticuatro. El Excelsior. It’s where we do our work, activating space.” For PODER high school youth member Inkza Angeles, whose 2019 poster against “The Monster in the Mission” hung alongside the 1969 Basta Ya! posters on the displacement caused by BART, remembering the past was critical to imagining the future. “No history, no self. What legacy are we a part of?” As for Yolanda, uniting culture and activism, “opened a whole new side, made me realize how much power I had, power united with other youth…”

I was interested in the alliances built across Third World organizations (the Panthers, the Young Lords, Los Siete), and even with radical working-class white organizations like the Young Patriots (Jason Ferreira writes about Los Siete’s Internationalism in Ten Years that Shook the City). Los Siete was a historical marker that defined how the community would see itself from then on, and filled a space in our own imagination.

It was also a period of contradictions within the community, when the powerful Mission Coalition Organization leveraged political favors for Federal funding, and spawned the network of nonprofits that serve the Mission community today, from health programs to employment and housing. I was curious about Los Siete’s approach to serving the people, like the free breakfast programs and the free clinic, that saw services as inseparable from political education and self-determination. “No one was getting paid,” Yolanda remembers. “No one was waiting for the War on Poverty money to come raining down.” Serving the people meant building relationships – the long-term view of organizing for the long-haul. As Los Siete organizer Roger Alvarado stressed, what united everyone was a common experience of police brutality and criminalization as a way of enforcing gentrification.

Together with Acción Latina’s staff, we created a series of public pláticas and a study guide to accompany the exhibit, asking critical questions around each of these issues. Local environmental justice organization PODER and radical historians Shaping SF organized a reading group of Marjorie Heinz’s Strictly Ghetto Property and a Bicis del Pueblo bike tour visiting the house on Alvarado Street where the officer was shot, the office where Los Siete published their paper, and the workers’ restaurant and the free clinic.

For the staff at Acción Latina, one of the most impactful aspects of the exhibit was how people came in to the storefront gallery, everyone with a story, either having lived through Los Siete or having had uncles or parents impacted by Los Siete. That response, from regular folks stopping in from off the street, across generations of the Mission, was as much an affirmation as the crowd at the opening or the other events we organized.

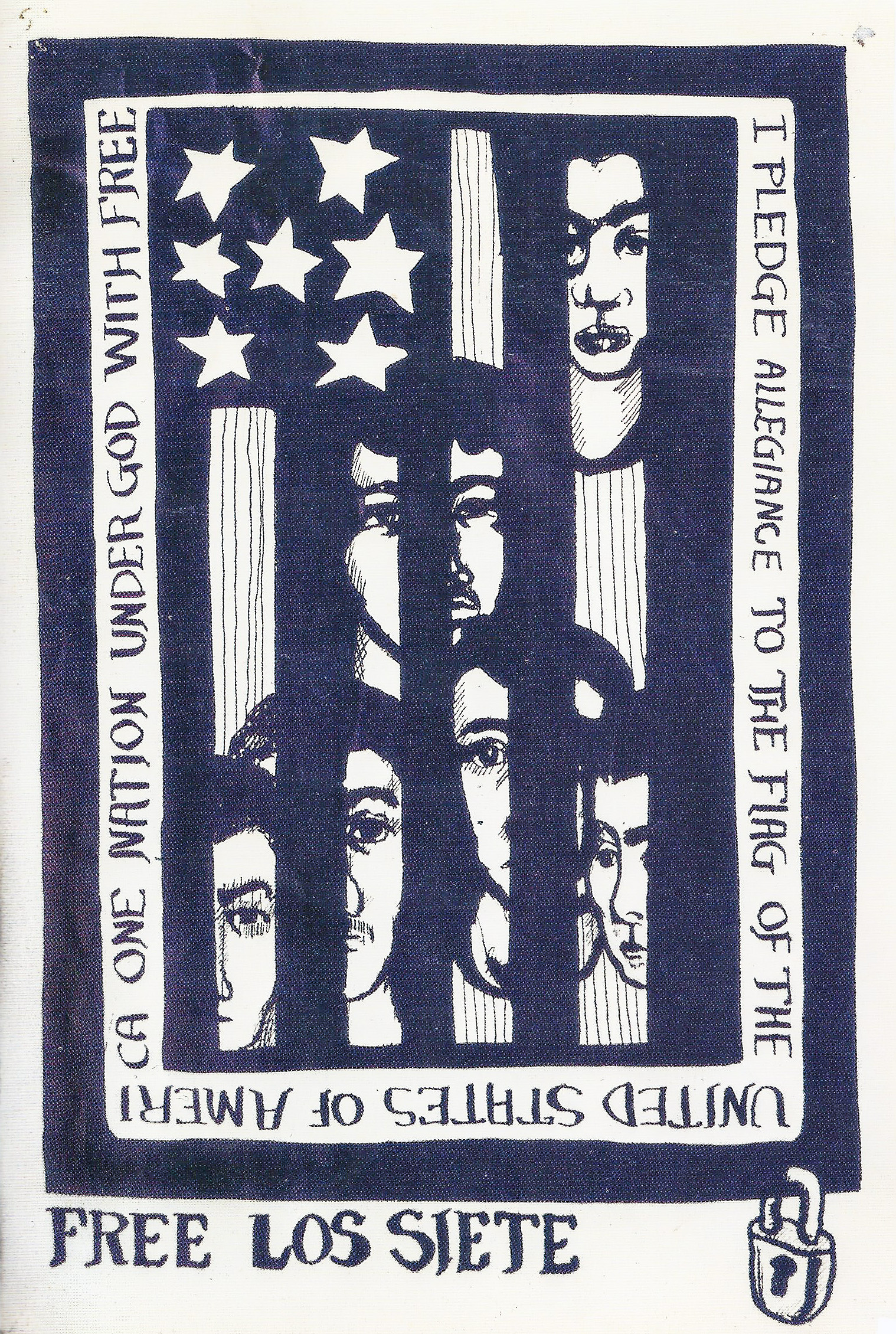

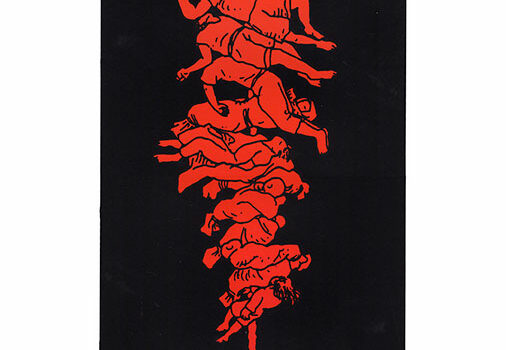

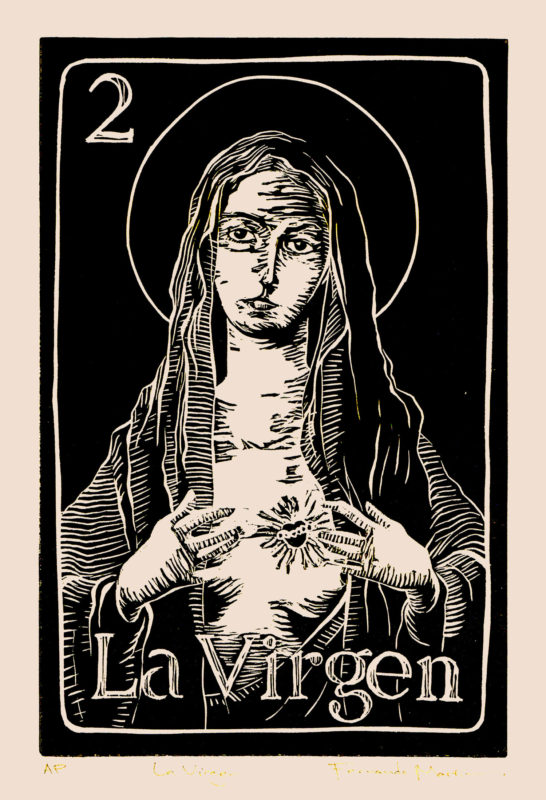

As an artist, I was especially curious about Yolanda Lopez’s role as a movement cultural worker, and the aesthetics she created for Los Siete. Yolanda’s graphics went hand-in-hand with Donna Amador’s writing and framing as editor of the Basta Ya!, the community newspaper created by Los Siete. This was the time of the explosion of underground newspapers, and the beginnings of the Chicano poster movement. Yolanda’s image of the stars and stripes enclosing the seven young men like prison bars, with a broken and unfinished pledge of allegiance around it, became the poster for the rallies and protests in front of the courthouse, a backdrop to the chants of “Que viva Los Siete, Que viva, Vivá!

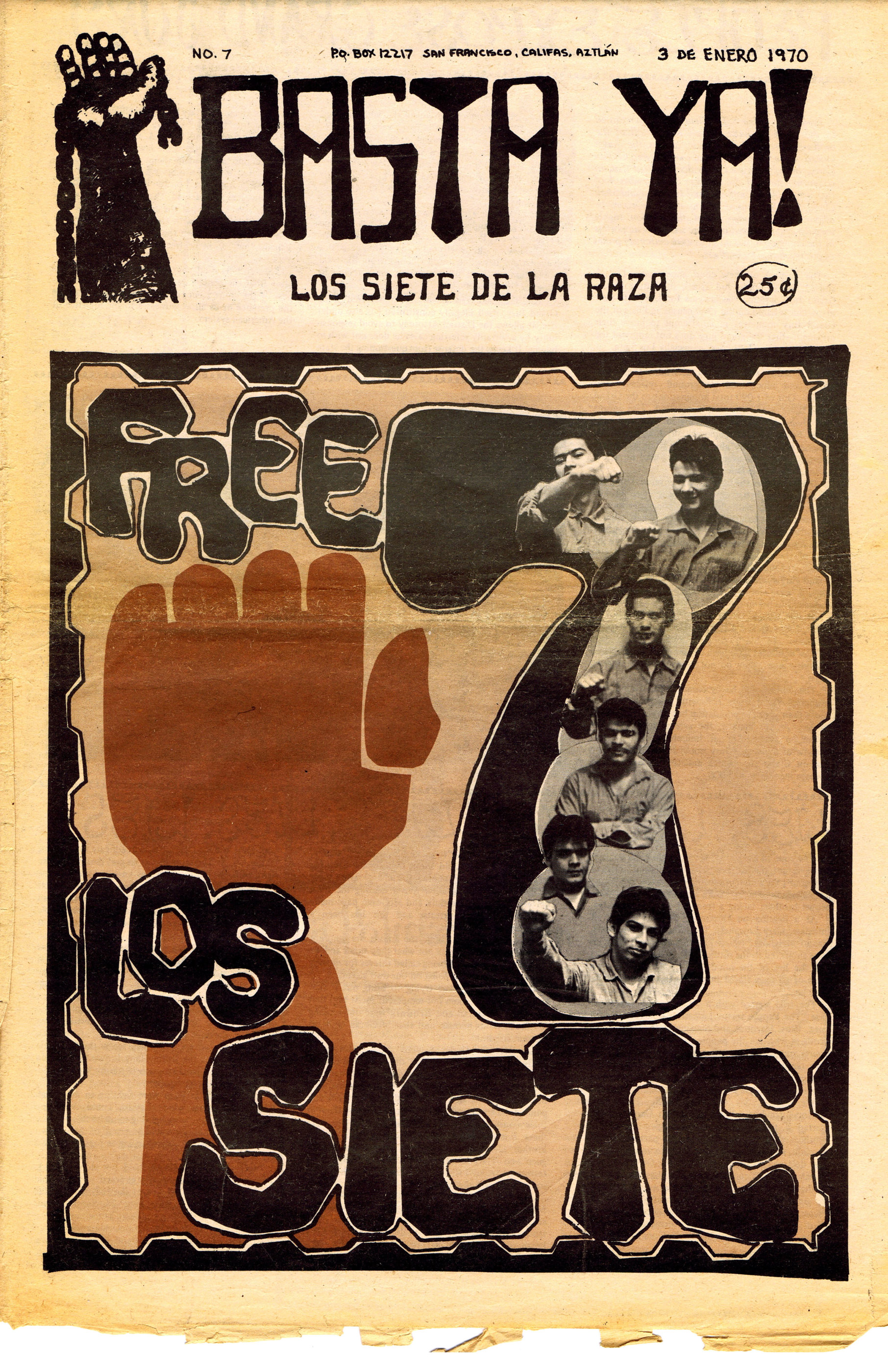

The number “7” became a unifying theme, from buttons to posters to newspaper covers.

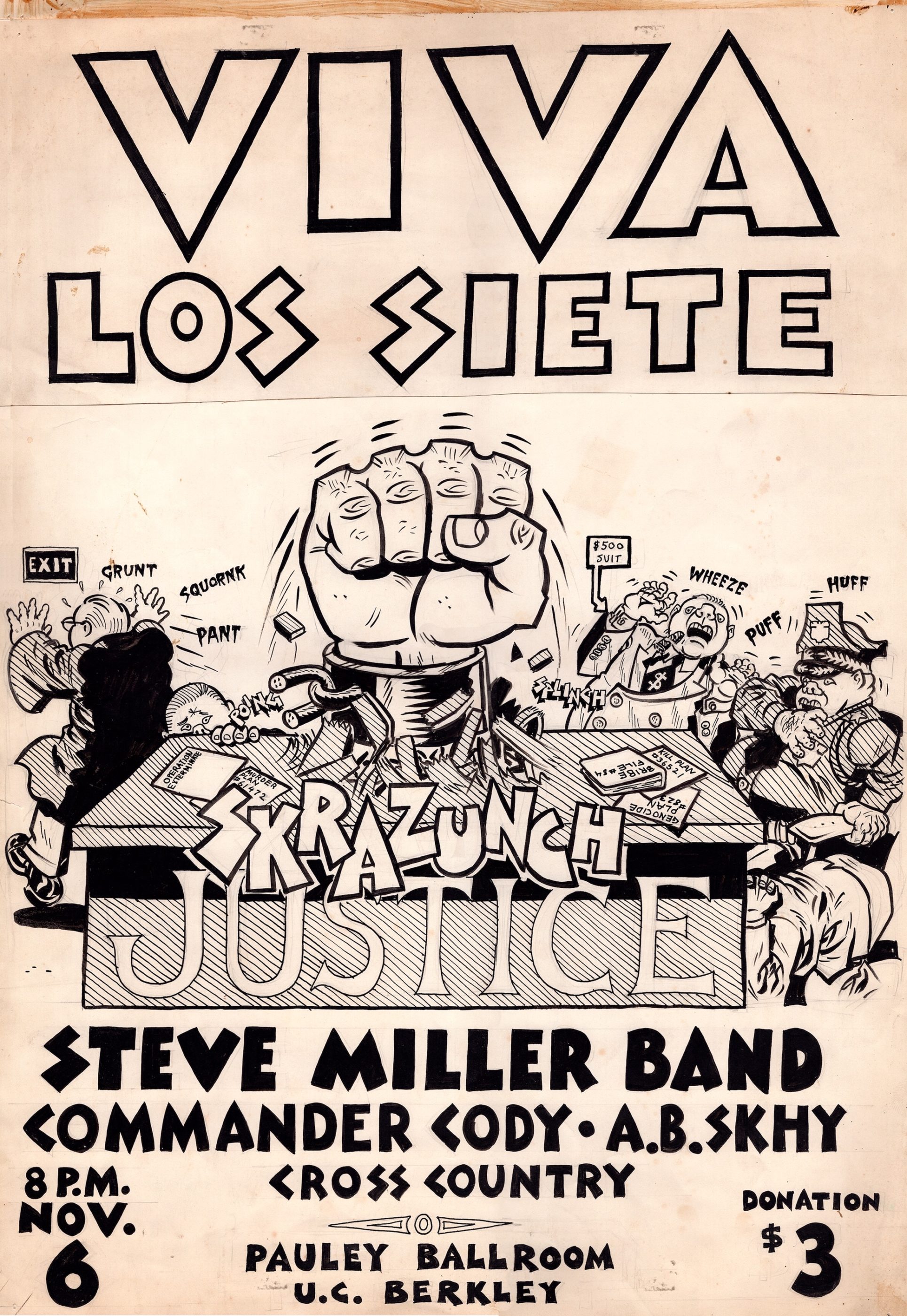

Other movement artists provided their versions, from Rupert Garcia and Spain Rodriguez to many anonymous poster-makers.

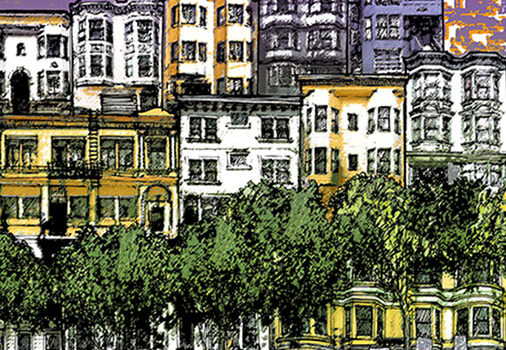

In the face of the terrible injustice of the case, the ongoing brutality of the police in the neighborhood, and the poverty and disinvestment to which the community was subjected, Yolanda Lopez chose to highlight the brave faces of the seven young men, the neighborhood children who dropped in regularly at the Los Siete defense committee’s storefront office, and the physical fabric of the neighborhood the Latinx community had made home. San Francisco’s Mission District was very much a hybrid culture in the 1970s, more Central-American than most other US Latinx barrios, with Puerto Ricans, Blacks, Native Americans and the old Irish residents contributing to the culture along with Chicanos and Mexican immigrants. It was this mezcla that the Basta Ya! attempted to represent and give voice to. As Yolanda put it, “I wanted to portray the community we loved. I was trying to convey the compassion of the brothers, and the compassion we had for the community.”

For the exhibit, I screenprinted one of Yolanda’s photo-collages from the Basta Ya!, a black-and-white image of neighborhood Victorians facing a park, with the words “Bring the Brothers Home.” We turned one of the Basta Ya! covers, a photo-collage of the seven inside a stylized “7,” into buttons for participants to make and give out at the opening. Yolanda insisted that we list each of the brothers, their names spelled out in handcut letters, just the way she did when laying out the Basta Ya! newspaper back in 1969-71. While I hung the show, Yolanda connected to the young people who stopped by to help, cutting and pasting the names, and sharing stories. Again, the affirmation of art in the storefronts.

For Yolanda, the lessons of organizing with and making art for Los Siete were to shape her work and her life: “In 1969, seven young men in the Mission District were charged with killing an undercover policeman. When I came to Los Siete, all of a sudden there was a need for the tools that I had, my art skills. With the experience of Los Siete, I understood what I was to do as an artist. My professional life followed that trajectory, as an artist for social and political change.” There was an energy to being an artist and an organizer in the midst of this community self-discovery and affirmation. “It was a thrilling time. It was fantastically dangerous. It was like war. There was a driving ferocious energy at the time. I made friendships that lasted forever. I learned what I wanted to be as an artist.”

Reflecting on the ongoing gentrification and policing of the community today, Yolanda says, “We need more art, we need more street theater, guerilla presence. Just do it, do it outside. The people need to see it… We need to make a bigger ruckus, continuous ruckus. We need to be impolite.” The art flows from the action: “When you’re making a ruckus, you have to be very clever.”

Thanks so much for this Fernando! I absolutely love Yolanda’s button sketches, so cool!

Such a great example of the role of culture in a movement.