Futuros Fugaces was a way to explore themes and relationships that have concerned me for a long time: what it means to reclaim ancestral knowledge, how we re-imagine the future, and what this looks like in the particular of the Mission/Excelsior Latinx community I’ve worked with for the last 30 years. Thanks to the SF Arts Commission for funding my first Individual Artist Grant! In imagining a Latinx futurism, the project took me in unexpected directions, beyond a more literal extrapolation of futurism, to a more mythical layering of Mesoamerican imagery as a way to connect past and future cosmic time.

My development as an artist is inseparable from my immigrant Latinx roots, and the experience of migration and dislocation to the heart of the empire. My work explores the reclamation of collective memory, and the transformative capacity of a futurist imagination rooted in culture. It is informed by the relationships and communities that have fostered me, and the experience of the struggles in these neighborhoods, in the face of massive displacement and gentrification, to define and redefine ourselves as an evolving and emergent Latinx community. I’m filled with the inspiration and hope of those who have made this city their own, and continue to fight for it and for a dignified future for the next generations.

Futuros Fugaces began with a series of interviews with local Latinx activists, elders, and youth, involved in the reclamation of ancestral traditions and the imagination of survival and adaptation. As the instability of climate change and pandemic is layered over the existence under racist policing and precarity in employment and housing, our communities continue to fight with amazing resilience. New waves of climate precarity call forth new forms of cultural resistance. I’ve been privileged to be part of a community that is reclaiming food traditions, herbalism, and urban agriculture, trying to rebuild connections to a land base in a difficult urban terrain that is often not where our ancestors come from.

Many are folks I know involved in the work of San Francisco-based PODER, or inspired by the just transition framing of Movement Generation’s Justice & Ecology project. Through the interviews, I wanted to explore how Latinx cultural practitioners were reclaiming and reimagining ancestral land-based knowledge. I was interested in how engaging in these practices could shape the struggle of young people to find a place in an often-alienating and difficult city, and how it could shape their fight for a transition toward a better and more just world. Finally, I was interested in how these practices shape how we imagine, physically and visually, a utopian de-colonized future for our urban communities. I asked folks to share their thoughts about these questions of reclaiming Latinx ancestral traditions, reimagining these practices for a contemporary urban culture, the significance of these practices to the struggles we face (gentrification, pandemic, climate change, policing), and how they inform our views of the future.

The work was always meant to deal with collective imagination during a period of emerging climate change and displacement pressures, but the pandemic gave the work a different urgency, as PODER’s staff and members reprioritize food and health security, and as the work of my interviewees in healing and plant medicine took on a new resonance. The Black Lives Matter uprisings, following the murder of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and other recent state killings, also brought policing and social control to the fore: other forms of precarity requiring strategies for resilience and transformation. Thanks to my first five interviewees: Tere Almaguer, Carlos Peterson-Gomez, Jacqueline Gutierrez, Edgar Xochitl Edgar, and Jorge Molina, and all the staff, elders and youth members of PODER who are an inspiration.

I view artwork as creating an arena for public dialogue, a dialectic process between the artist and world around them. While I originally envisioned the work culminating with a physical exhibit, workshop, and gathering with the community leaders I interviewed for the project, I was able to arrange an online Facebook/zoom exhibit with the support of the SF International Arts Festival, allowing the project to fulfill its goal of amplifying community voices and cultural traditions as part of organizing around climate change. The conversation was held via Facebook/Zoom, between the artist and three of the people interviewed for the project, herbalist/organizer Tere Almaguer, educator/artist Jacqueline Gutierrez, and gardener/ecologist Xochitl Flores, and the public, with the visual work as backdrop/instigator to the bigger issues the community is grappling with. But the actual gathering or convivio, coming together to share experience and co-create our visions of the future in a shared physical space, will have to wait for after shelter in place. When we do, the conversations will be different than originally envisioned, as we think collectively about what a Latinx futurism means informed by the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter uprisings.

The images

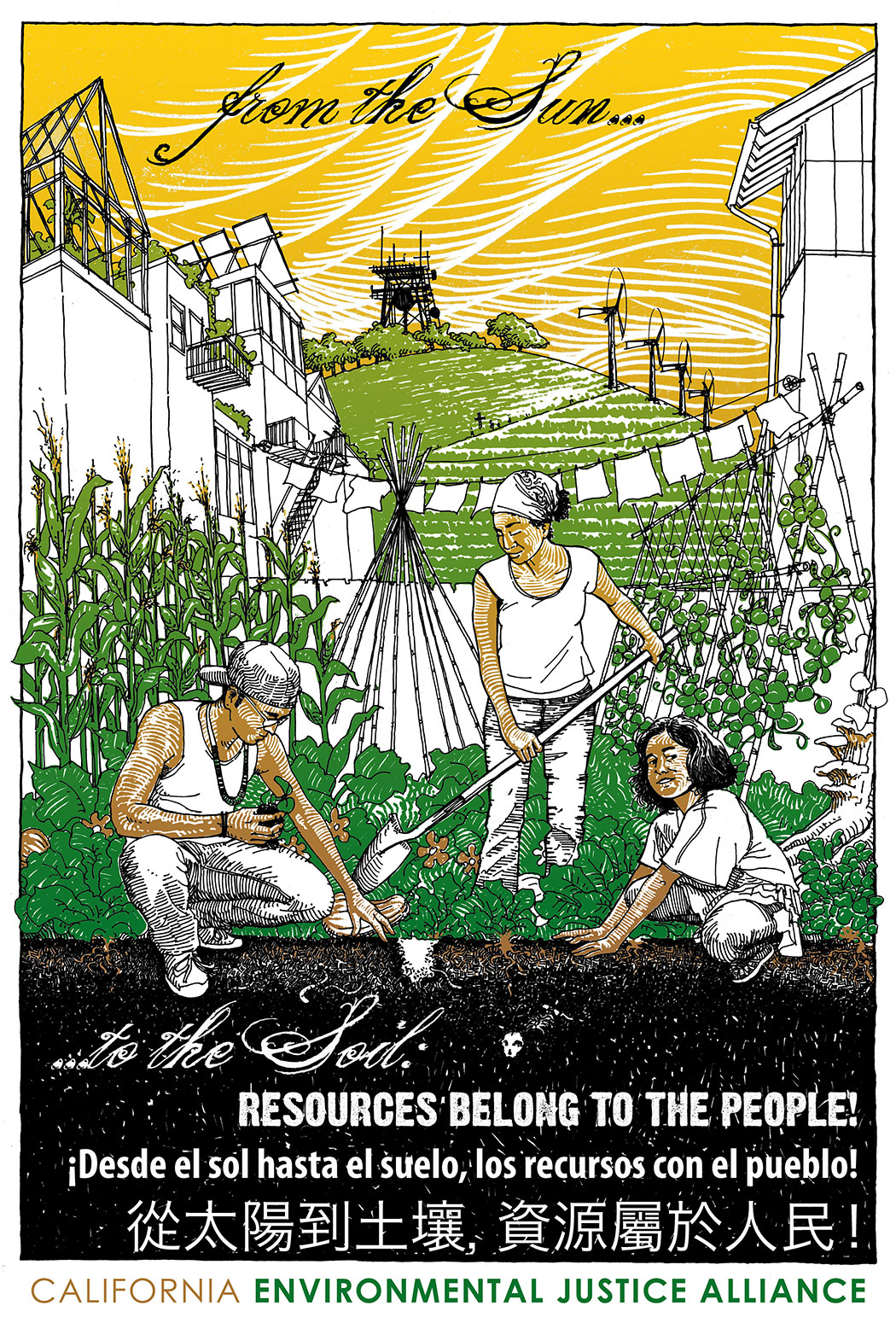

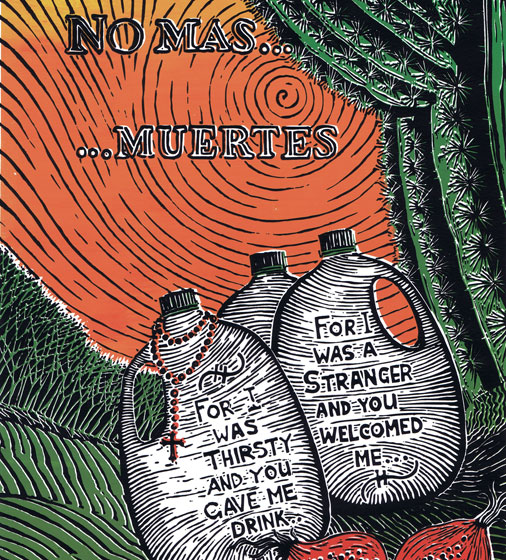

As a child I was fascinated with science fiction (and continue to be). My imagery often juxtaposes present conditions with “what-could-be,” a utopian impulse to imagine possibilities of transformation. The utopian narratives we are familiar with have typically been trapped in Eurocentric and technocratic aspirations. Imagining a dystopia is easy – Netflix is filled with dystopian shows. Imagining a utopian future time has to be more than sticking plants, greenhouses, solar panels and windmills on top of buildings (though that is surely part of it, and some of that comes into my images). Utopia is not just the past (paradise, the Great Unity), or accessible only in death (heaven), or a thought experiment that exists elsewhere (More’s Utopia, Peach Blossom Spring), or in an extrapolated future (Bellamy, Morris, Callenbach, LeGuin, Piercy, Starhawk).

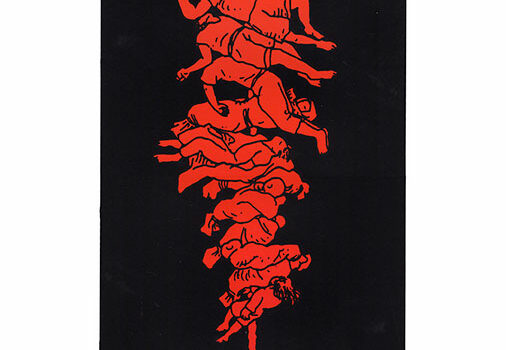

The emergent utopias of our communities of color will not be sterile or sanitized; they will contain hints of the dystopias we’re already living through, and they will contain the messiness and contradictions of our cultures, a collage of rasquachismo, rooted in a reclamation of ancestral traditions and collective memory to urban land struggles and queer ecologies. As I thought of a Latinx futurism, the cyclical nature of Mesoamerican time, cyclical, perhaps helical, expanding outward but always returning. Or perhaps it is a simultaneity of times, layered in parallel existences informing the present, accessible through ritual and ceremony. Mesoamerican time gave me a layering of myth and history and contemporary cultures and utopian visions. Utopia has to coexist with the present, accessible through our cultural practices and our arts, to inform our actions. Glimpses or shadows of that utopia found their way into these images.

In imagining place, I have to acknowledge the ancestors who took care of this land for thousands of years for us to be here, and the struggles still ongoing, to claim recognition, to claim access to their own land, to claim sovereignty and autonomy. This is unceded Ramaytush Ohlone territory. One example of this ongoing struggle of indigenous people is the work just across the Bay of the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust.

The imagery that came out of this was not a literal interpretation of the interviews, but became magical-realist companions to the interviews. The portfolio and interviews will eventually be documented in a published zine, but for now the first 8 plates are shared below. The images were created in pencil, scanned to create the line drawing, then watercolored and scanned again, and additional colors and backgrounds applied digitally in Photoshop. Over the next few months I’m aiming to complete 5 more images, to have a set of 13, one for each month of the Mesoamerican calendar.

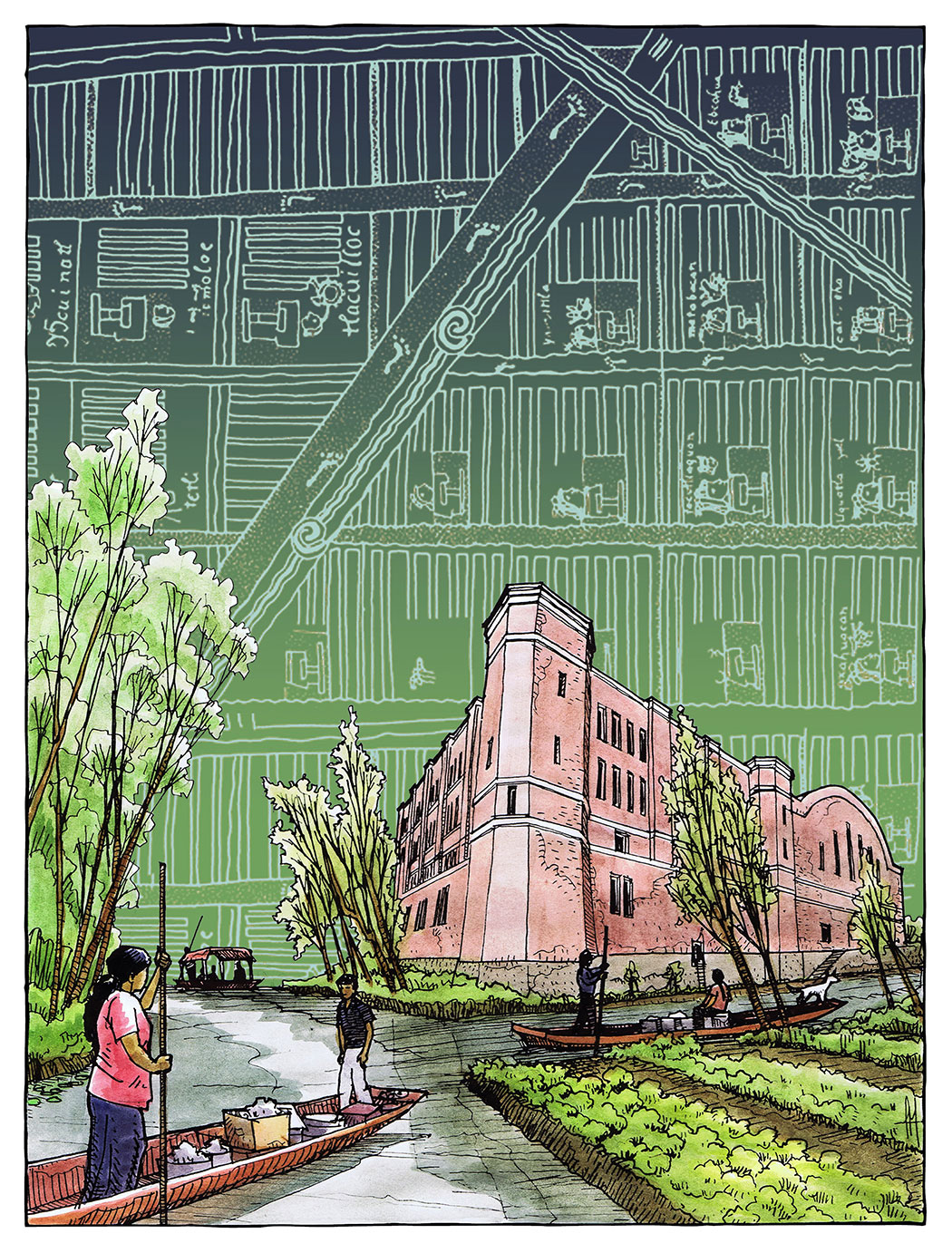

Plate 1. Armory Chinampas.

This was an image I’ve had in mind in some form or other since the late 90s, when the old Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition crashed a party held by the Mayor to celebrate turning the dilapidated National Guard Armory into a server farm. For years the city had discussed turning it over to the community for a dollar, but no one had the cash to bring it up to seismic safety standards, and finally the Mayor just gave it to his tech investor friends. The server farm didn’t last long, and then it became the home of Kink.com, till that also went away. Today, with National Guard troops mobilizing around the country to quell uprisings, the building had a different resonance. I remember writer John Ross telling the story of how Mission activists had surrounded the Armory in 1966 to stop troops from mobilizing to put down the Hunter’s Point uprising.

The Armory sits over a natural spring, and its basement floods with every rain. I originally imagined it sitting on a lake, with squatter shacks hanging off its walls like the hills above Guayaquil or Caracas. But as I thought more of rising seas and adapting to the new climates we will all be facing, the image that stuck was of the chinampas, the floating gardens of Tenochtitlan, still practiced in Xochimilco. Will our streets become canals, traveled by colorful lanchas, the sidewalks farmed in chinampas wherever the old creeks and marshes, now paved over, return to their watery state? The background image is adapted from a map of chinampa farm tributes, ca. 1542, from the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Mexico.

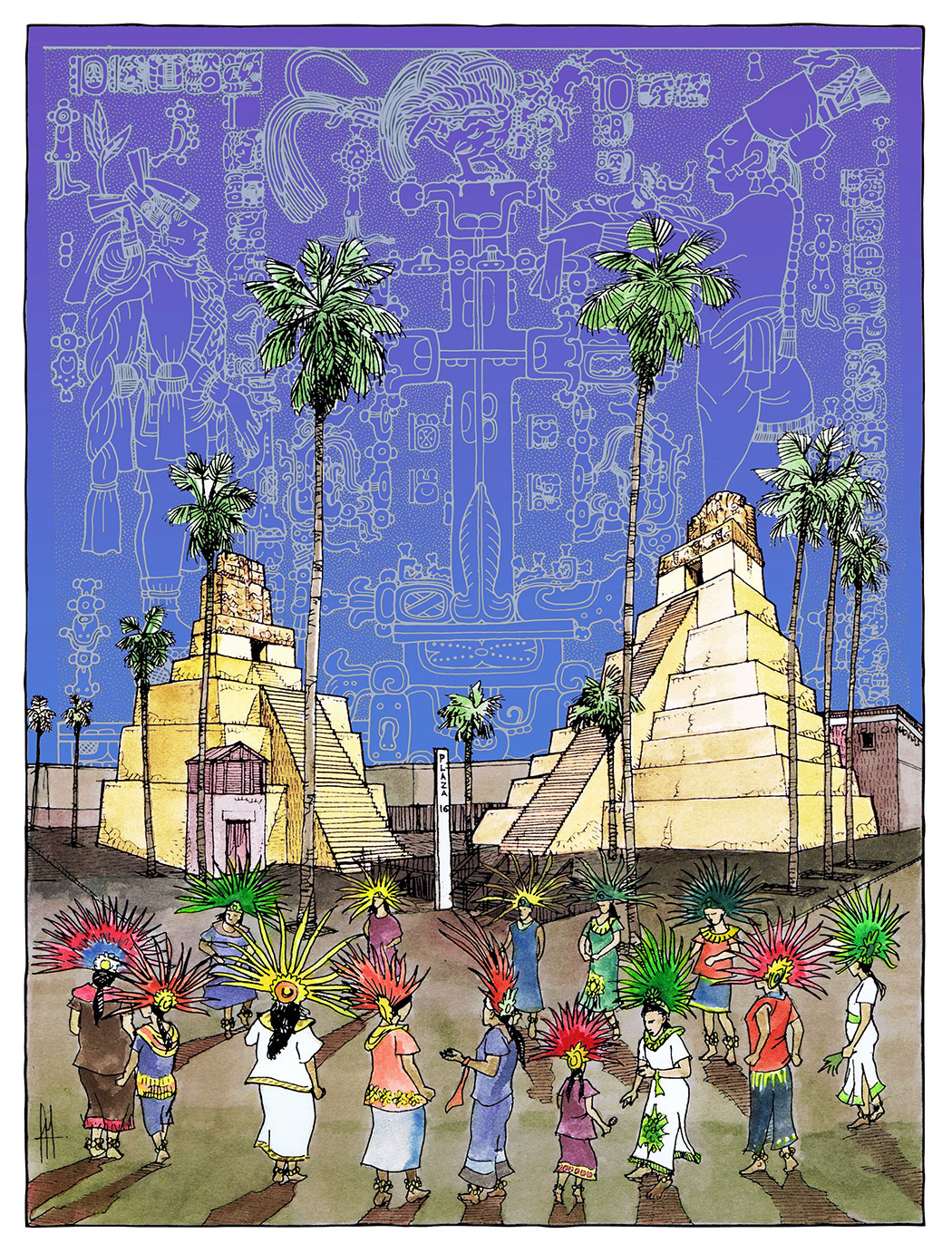

Plate 2: Plaza 16.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the BART subway lines coming to the neighborhood in the early 70s was the first large-scale attack at erasing the Mission’s Latinx community. BART was part of a massive urban renewal plan, intended to demolish huge swaths of the neighborhood, and rebuild it with commercial and residential towers connected to the new commuter line. Seeing what had already happened in the Fillmore and was happening South of Market, the Mission community mobilized successfully to stop it, but in the process of building the subway, what was left was a dilapidated one-story building with a chain pharmacy, fast food, and a parking lot, in the middle of one of the densest neighborhoods in the West. The intention was always there to remake it in the image of capital, waiting for the right stage of the gentrification process to see it fulfilled. For the last few years the community has again mobilized to stop this new “Monster in the Mission” at the 16th Street BART station, proposing instead a community-created vision with affordable housing, community centers, and social services for the large residential hotel community surrounding these blocks.

My image was not a literal interpretation of what could be at 16th Street, but a reclaiming of ceremony and sacred space at the center of that reimagination: the temples of Tikal rising on either side of BART plaza, and the ceremony of Danza Mexica holding space for a future that includes us in it. In my interview, Mission elder and musician Jorge Molina said, “Cada humano sobre nuestro planeta es un chaman. Every human on our planet has their own medicine… There is something pagan in every ancestral tree.” Within capitalism, the pagan either doesn’t exist, or becomes a sub-market for consumption. How do we re-incorporate land-based ritual and ceremony into our visions for the development of the city? The sky is adapted from a drawing of the World Tree / Milky Way by archeologist Linda Schele from the Temple of the Cross in Palenque.

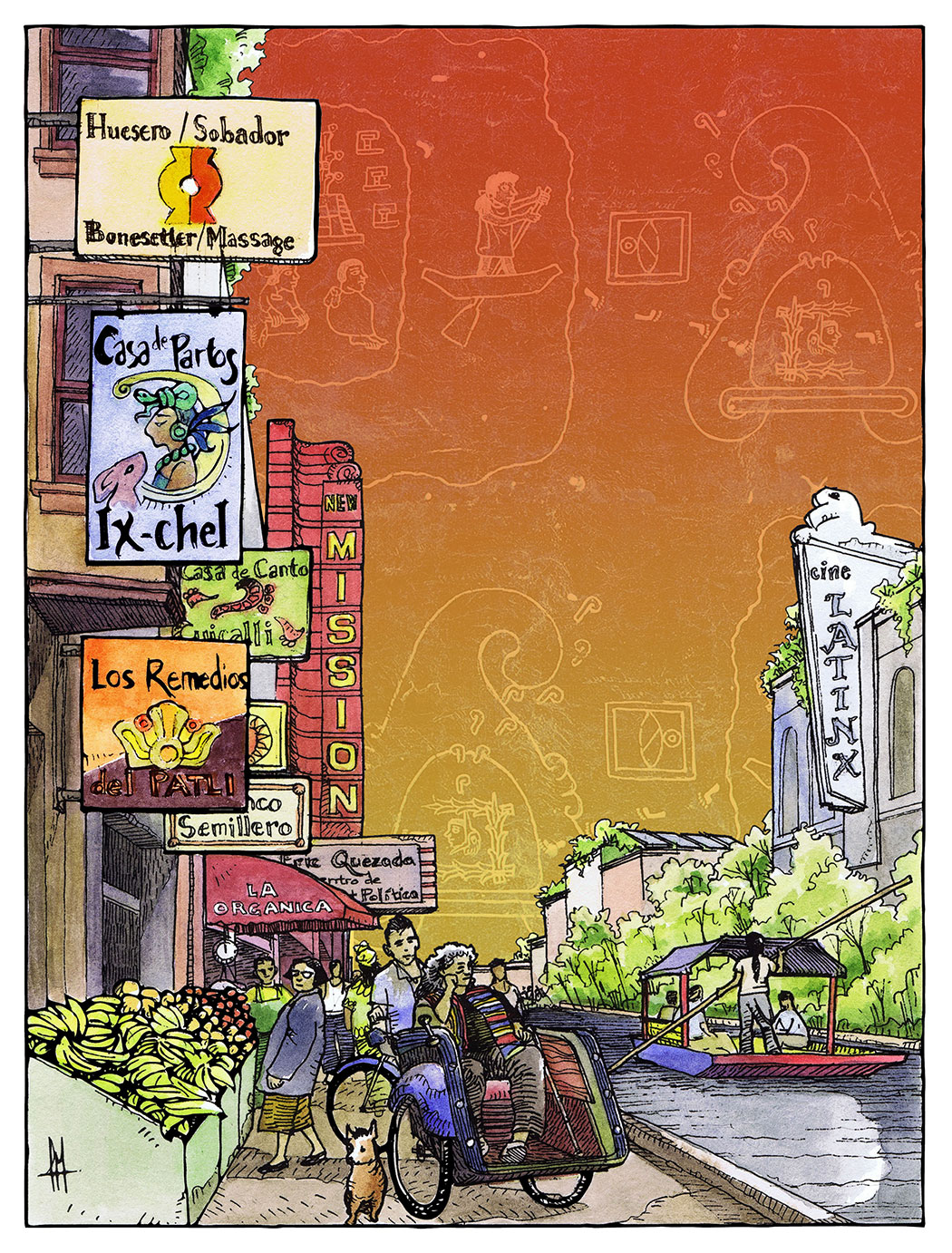

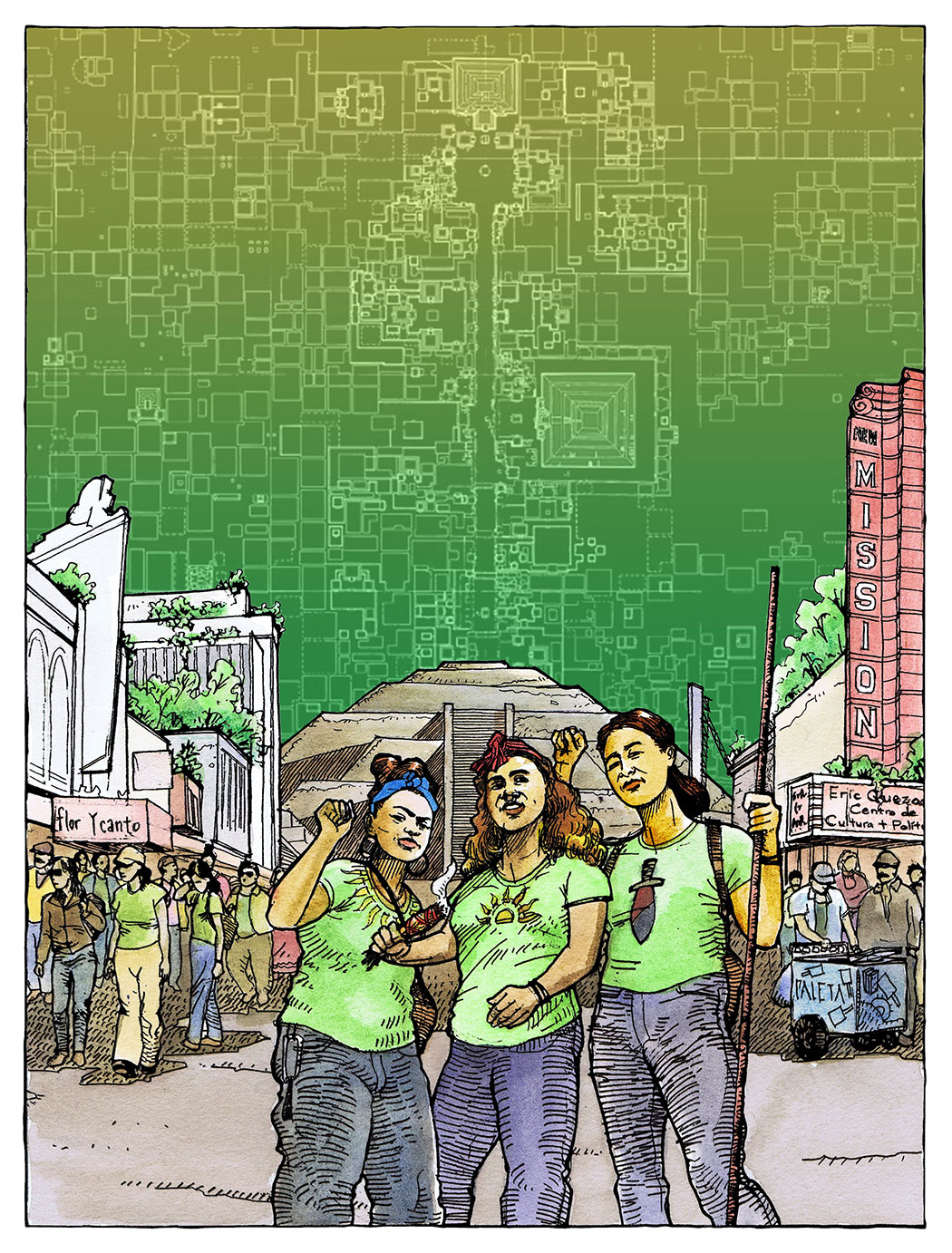

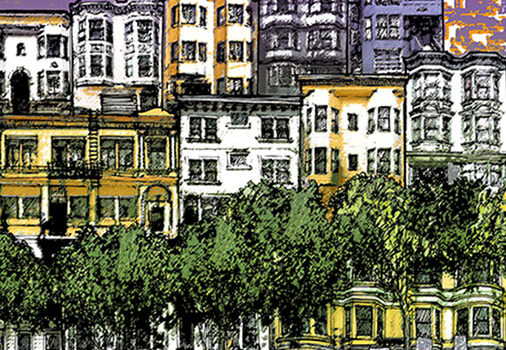

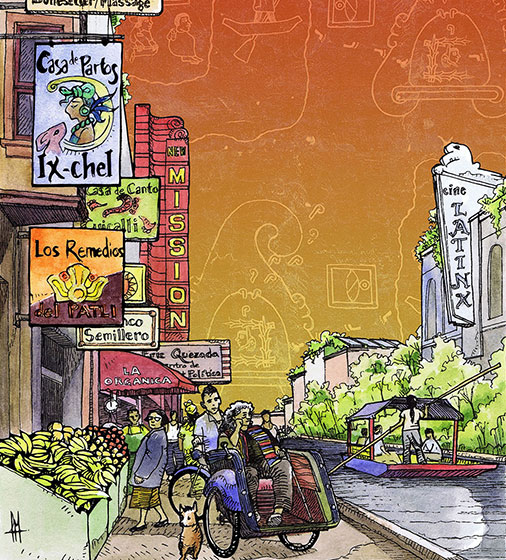

Plate 3: Mission-Aztlán.

When I arrived in the Mission in the early 90s, I was drawn in by people speaking my own language, the mezcla of words and colors and skin tones, and the street and its storefronts and signs reflected this: taquerías next to cheap import dollar stores, pawn shops, computer repair and socialist bookstores, Yucatecan next to Vietnamese, but then too, over the years, the signs of gentrification, the mobile phone franchises, the new theater redesigned exclusively for 20-something millennials, and trendy too-expensive coffeeshops. In 2009 I was involved in fixing up 518 Valencia as what was to become the Eric Quezada Center for Culture and Politics, and it got me to thinking, what would the store signs look like in a utopian future? What would markets and trade look like when the oppressive fixtures of corporate capitalism were removed, and when blind consumerism was replaced by things that mattered, would the dollar stores be replaced by community social centers, neighborhood health clinics and birthing centers, produce and medicinal herb shops straight from urban agriculture plots. This could be the new Aztlán, the home for the cosmic mezcla of humanity. The stories of Aztlán were of a place surrounded by waters, where a white heron flew, from which the Nahuatl-speaking peoples headed south to settle in the basin of Mexico. Could it have been a place like this? The sky is adapted from a map of the commencement of the migration from Aztlán from the Codex Boturini.

Plate 4: Mission-Temple of the Moon

Looking south down Mission Street one can imagine the journeys we travel back and forth from our homes in the south to our new homes in El Norte. And while Mission Street plays into the colonial legacy of the “Camino Real,” trade routes connecting native peoples from the southwest to Oregon existed long before the Spanish/Missionary conquest. Today the street is a site of low-rider cruises, rallies and protests, and continuing fights over gentrification, of trying to remake the street as a high-end luxury condo district. But in this imaginary, the ancient city of Teotihuacan traces its long lineage through to these streets created by colonialism and imperialism, reminding us that the future is not yet solidified, that our young people can still shape it. In the face of uncertain futures, it’s been inspiring to see how youth find their voice and their power through organizations like PODER. The streets are theirs. And it is vital that we see that ancestral spirit flowing through them. We are lucky to share both in their strength and optimism, and in the legacy of the knowledge we carry from ancient times. Jacqueline Gutierrez, who supports youth organizing at PODER, spoke of how she has always had strong and powerful young womxn coming from the community to guide how her classes run, watching them all step into their own power. I tried to convey that sense in the young womxn owning Mission Street. The sky is adapted from Rene Millon’s map of Teotihuacan’s Avenue of the Dead, with the Temple of the Moon at the top.

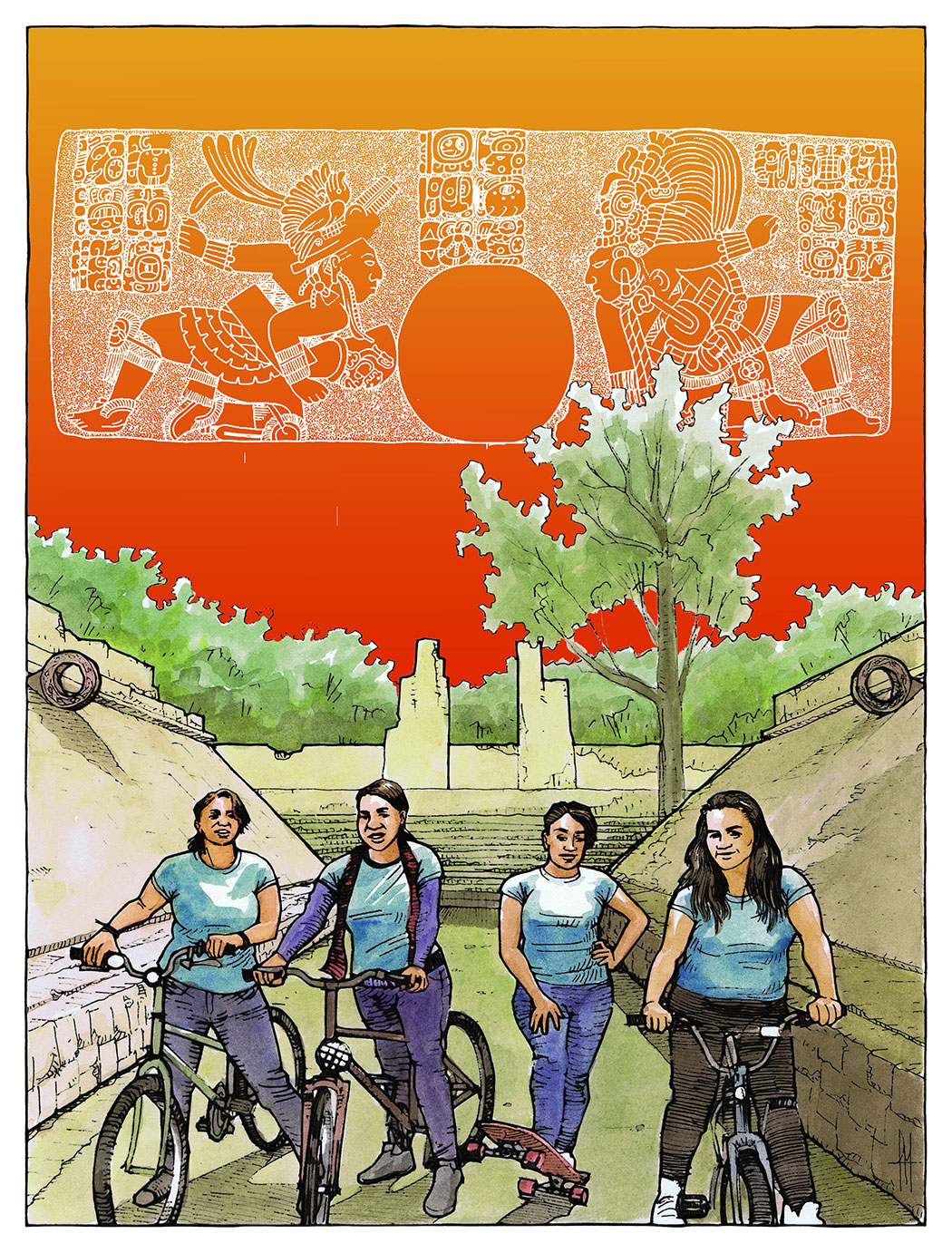

Plate 5: Bicis / Ball Court

One of the projects PODER has engaged in for years is Bicis del Pueblo, getting young people in the community on bikes, fixing and making their own bikes, taking to the streets. The bike to me was not just about transportation, but a different way of relating to streets, to movement, to what our bodies can do. Bicis is about how young people (and old) can make the streets their our own, the way the ancient Mesoamerican ball games are “our own,” and the origin of most modern team ball sports. In the interviews, I spoke with Carlos Peterson-Gomez about the need for rites of passage in our communities, both for boys and for girls, for finding that place in the world which is our own. A Latinx future, I think, will be in part defined by how we re-incorporate these rites into adulthood. I saw the bicis in the ball court as a space where we reclaim what is important from the past on our journey to adulthood. The sky is adapted from an inscription of a ball game from Toniná, Chiapas, by Ian Graham.

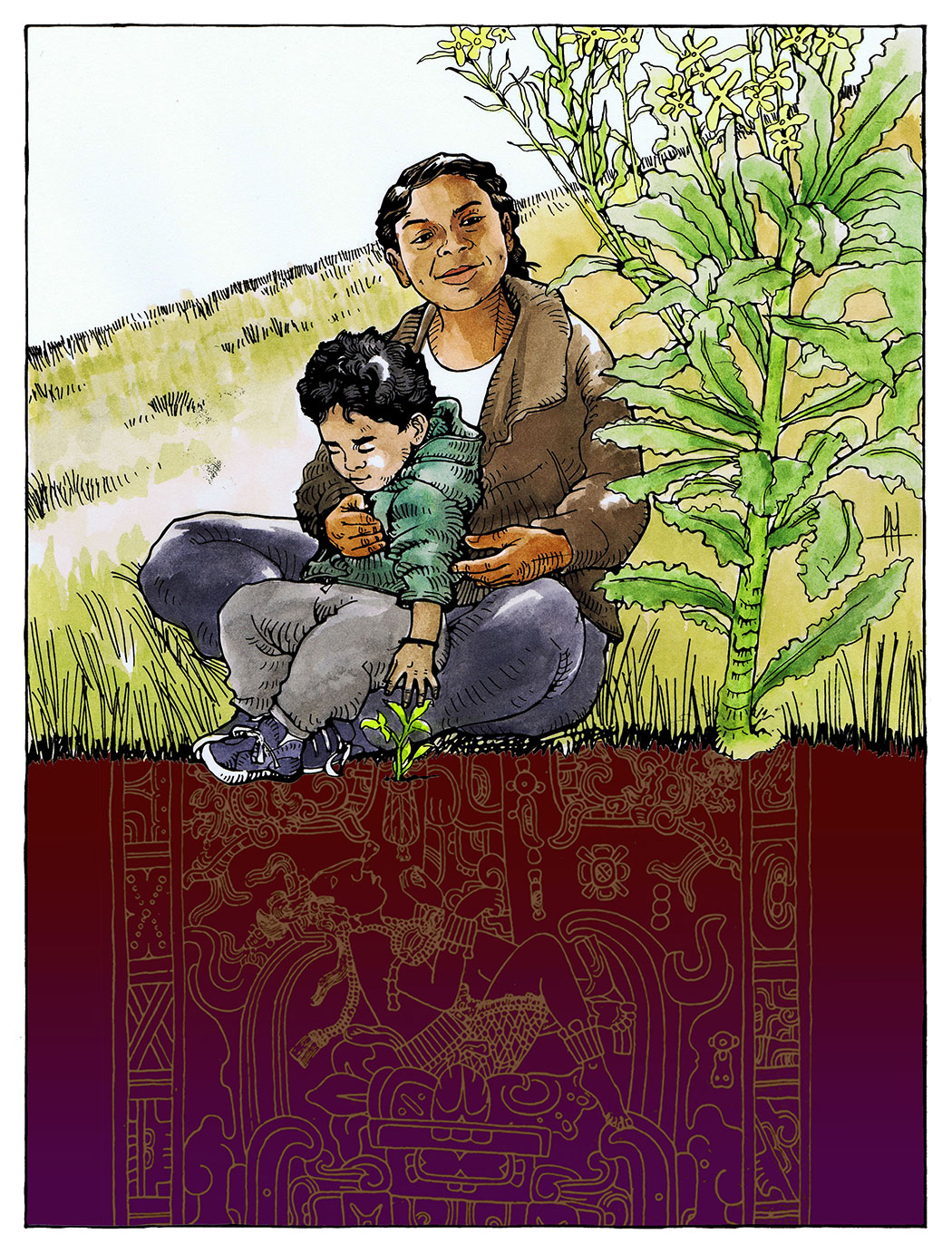

Plate 6: Desde Abajo

Re-connecting to land-based ancestral knowledge takes on a very different form for those of us who live in dense urban areas like San Francisco. PODER’s youth began a movement to connect back to these histories through Urban Campesinx, a food justice and leadership program. Even here in San Francisco, we can find areas of land that others might think of as the leftovers, to dig deep. For the last three years, PODER has engaged in an urban agriculture experiment on the southern edge of the city, building a farm on Public Utilities Commission land. Hummingbird Farm / Huerto Colibrí, has become not only a place for growing food and plant medicines, but a place for ritual and ceremony, and a place to bring our children to be in the earth (when so much of the soil we might have access to in the city is polluted with lead or arsenic). Imagining the future is often visualized in the sky: flight and space, the moon and the stars and planets beyond our own. But there is no future without soil, without that connection back to ancestral time that flows from past to future. Here Alondra and her son reach down to the growing plants. It’s been amazing to watch this child grow together with the plants, from the time they were a newborn. Below them, Pakal reaches up from the underworld to the world tree, adapted from a drawing by Merle Greene from the Temple of Inscriptions in Palenque. I think of the Mayan tradition that Tere Almaguer recounted to me, of the connection we have with the place where we take our first breath.

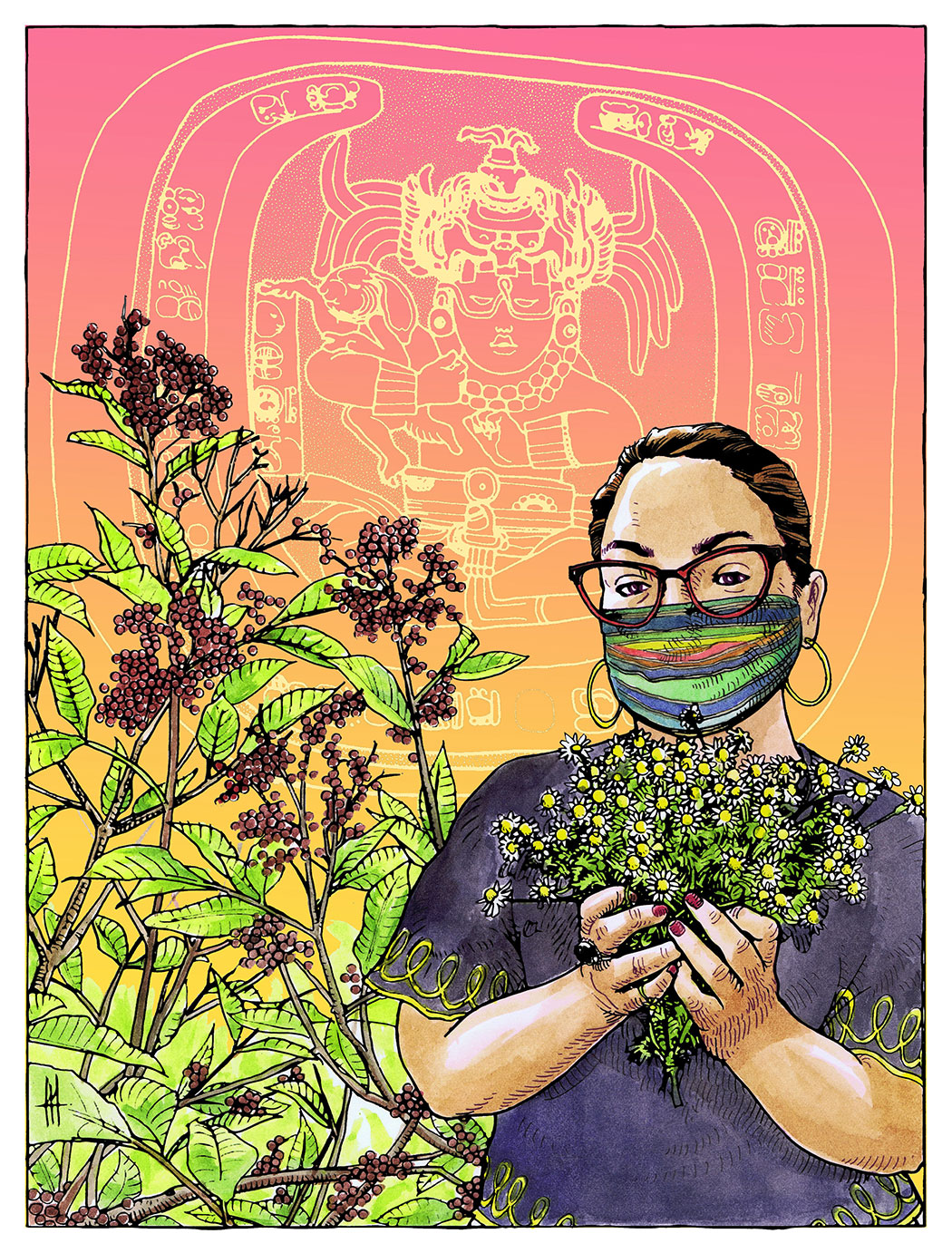

Plate 7: Saúco y Manzanilla

My first interview for this project was with Tere Almaguer, a long-time organizer with PODER, an herbalist, and a danzante Mexica. As people of color and immigrant communities living in a city in the heart of empire, there are so many battles to be fought: against the racist social control of the police, against the evictions and displacement, against the revanchist gentrification that tries to remake our communities as playground for the rich after decades of disinvestment. But the struggles are long. In this particular land, the struggle of native people has been going on for over 240 years. For us as descendants of the mezcla, of the Latinx diaspora, the struggles are external and internal, oppressions often within ourselves. For the struggle to be resilient for that long haul, we must care for ourselves, healing our bodies and minds and communities. Different from technocratic futurism, a Latinx futurism would embrace the technologies and ancestral knowledges that will allow for our future resilience. Tere has been part of the Ancestral Apothecary cohort of people of color reclaiming herbalism and other traditional practices. In our interviews, she talked of the elderberry growing at Hummingbird Farm, and other immune-boosting plant medicines, so needed in these times when our systems are facing the onslaught of diseases, toxins and infections unleashed by capitalist exploitation. I had not intended this series to have portraits of real people, but as I worked on the interviews, I could see their expressions as portraits of our possible futures. I borrowed from a couple of photos of Tere, one holding a chamomile bunch from Hummingbird Farm, and another wearing a mask at a social distancing car protest demanding homes for our unhoused neighbors. The sky is adapted from a drawing by Linda Schele of Ixchel, Mayan goddess of healing and midwifery, whose inscriptions look suspiciously like Tere’s cat glasses.

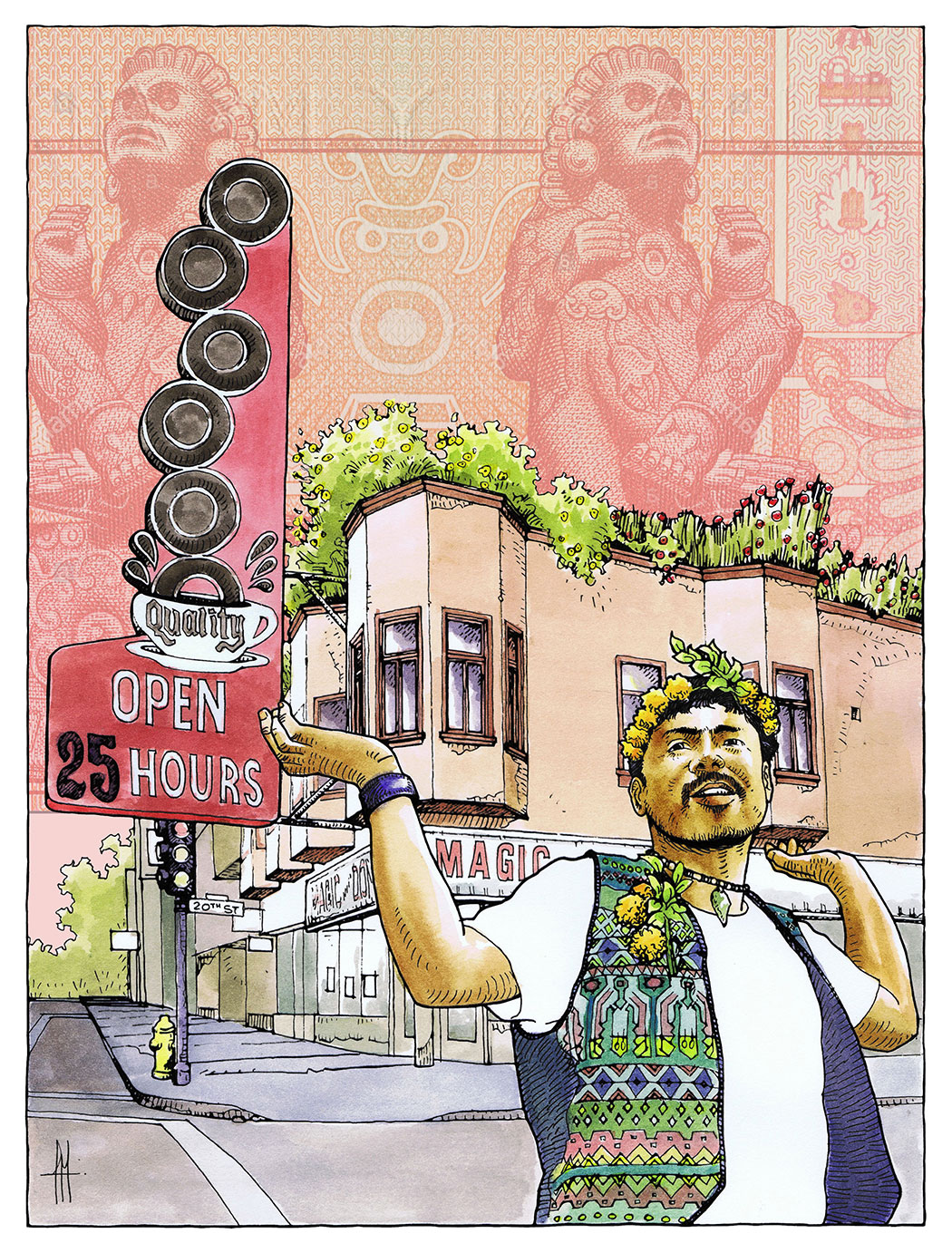

Plate 8: Xochipilli Magic

Edgar Xochitl is the farm manager at Hummingbird Farm. I first heard Xoch at another of community space stewarded by PODER, el Jardin Secreto in the Mission, speaking on queer ecology. Queer ecology gave me a new language for understanding the world around me, beyond the binary of Linnaean plant classification. In our interview, Xoch talked about what we wanted to keep from our ancestral traditions, and where we needed to look beyond, or what suppressed knowledges we needed to raise up. Thinking of the ancient Mayan and Aztec cosmologies, formed by their own empires and patriarchies, and our understandings of them today shaped by colonial influence, I tried to find where the queer magic could be found. Xochipilli stood out as a trickster within the Aztec pantheon, who somehow snuck in, upholding queerness and fun and flower magic. The sky above the Magic Donut place is an image of Xochipilli from the back of an old Mexican 100 peso bill. Here is more wisdom from Edgar Xochitl.

Somehow, I knew Magic Donuts would make it into this series. Like the Armory, this is an image I’ve wanted to work on for a long time. The sign is gone now, as is the donut shop. When I moved to SF in the 90s, it was still the place where late night punks, homeless folks, and cops on a donut run convened to create a certain kind of fluorescent-lit magic 25 hours into the night. Before it was “Magic Donuts,” it was “Hunt’s,” where the Mission’s revolutionary organization from the late 60s/early 70s, Los Siete de la Raza, sold their newspaper to educate the masses. Thank you to Vero Majano and to Erica Dawn Lyle’s excellent Scam! for sharing the history of Hunt’s.

Muy rico su trabajo. Estoy en Belo Horizonte y tambien tengo uno proyecto de presevar las nuestras tradiciones.

Mira en http://www.instagram.com/sementemaker

Donde encontramos este artista en las redes sociales por favor?

Fernando es en instagram: https://www.instagram.com/el_compay_nando/