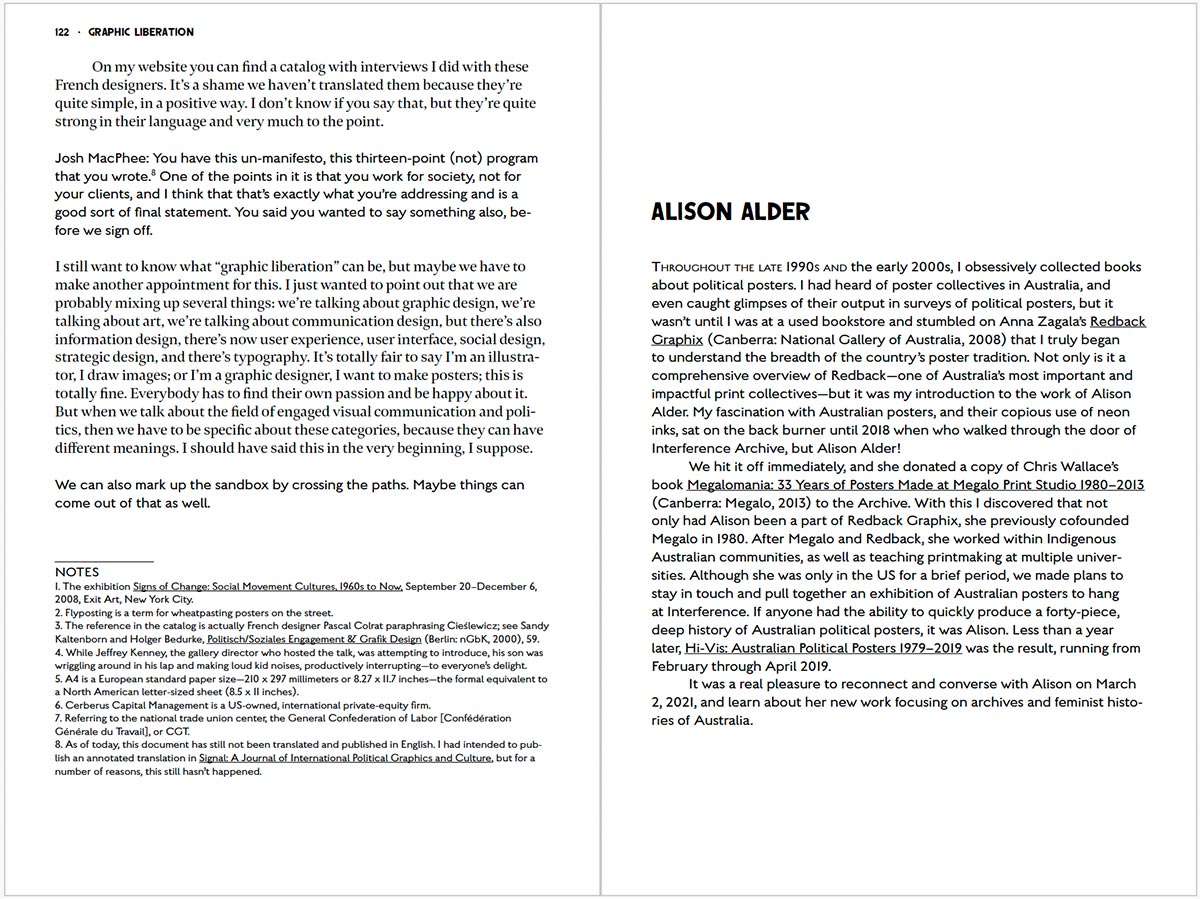

I’m very excited to announce my new book, Graphic Liberation: Image Making and Political Movements, which is being shipped from the printed this week! I’ve been slowly and quietly at work on it for the past couple years, transcribing and cleaning up the best parts of my Graphic Liberation online conversation series to create a book which I hope will be an extremely useful tool for political graphics producers, social justice oriented artists, and politically engaged designers. It is a book about art and design, but it is not an art book, per se. Rather than focusing on images of work, it focuses in on multiple cultural workers’ processes: what they do, how they do it, who they work with, and why. Overall I’m humbled to have been able to discuss all these things with some of the most dynamic social movement artists of the past 50-60 years: A3BC, Alison Alder, Tomie Arai, Tings Chak, Dignidad Rebelde (Jesus Barraza and Melanie Cervantes), Emory Douglas, Daniel Drennan ElAwar, Avram Finkelstein, Sandy Kaltenborn, and Judy Seidman.

Rather than generate a bunch of hype-focused promo language, I’m just going to post an excerpt from my introduction here:

“For much of my life as a cultural producer I’ve been trying to find a place to belong. Neither formally trained in art or design, what I do and what I make have never felt truly at home in either domain. My art isn’t art-y enough and my design isn’t design-y enough; didactic political graphics, posters for movement actions, and calls for solidarity always feels a little awkward in either sphere. This likely would have mattered little if I had come up in a moment of social movement upheaval, or even one where political organizations valued culture. But I didn’t. So, I’ve carried a chip on my shoulder for thirty years, trying to distance myself from the seeming frivolity, self-referentiality, and entrepreneurship of fine art as well as the commercial focus and aesthetic conventions of graphic design, all the while still needing to make money to live. The 1990s and early 2000s was a raucous time, trying to prove that what I was doing could be a valuable aspect of political struggle, usually feeling like my pleas (and work) were falling on the closed minds of union officials, community organizers, and leftist activists alike.

Much has changed over the past twenty-five years. Everyone from the executive directors of social justice nonprofits to funding agencies to street-level activists are talking about art as central to social transformation. This concept moved quickly from underground mantra to mainstream gospel—I passed a woman on the street yesterday wearing a t-shirt that proudly proclaimed “I believe in the power of art.” Yet few seem to have stopped to ask: if art is necessary for social change, how exactly does that change happen? And what role does art play in it? It is often claimed that art operates in the realm of the affective, yet social change is best marked by a transformation of concrete material conditions. What actual role does culture play in this? If it has power, what is it?

In trying to navigate these questions, and research the historical roles culture has contributed to people organizing to transform their lives, I loosely developed a concept with Dara Greenwald which we called “social movement culture.” To return to the seeming contradictions of the epigraphs above, rather than trying to be art or design, why not both? Or neither? Maybe a binary is not effective at describing the actual conditions of the production of culture for political movements. Maybe this kind of movement culture is a distinct tradition from both art and design.

. . .

This book is an assembly of edited transcripts from a set of conversations I held in 2021–2022 with ten social movement cultural producers. Rather than introduce them individually here, each conversation has its own opening comments. But I will say that I am extremely privileged that each of my interlocutors agreed to participate in this project, each has and continues to contribute greatly to movement culture and offer profound insights into it here. Originally framed as the Graphic Liberation discussion series, these exchanges evolved out of a visiting artist residency I held at Colgate University which was specifically shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic.

. . .

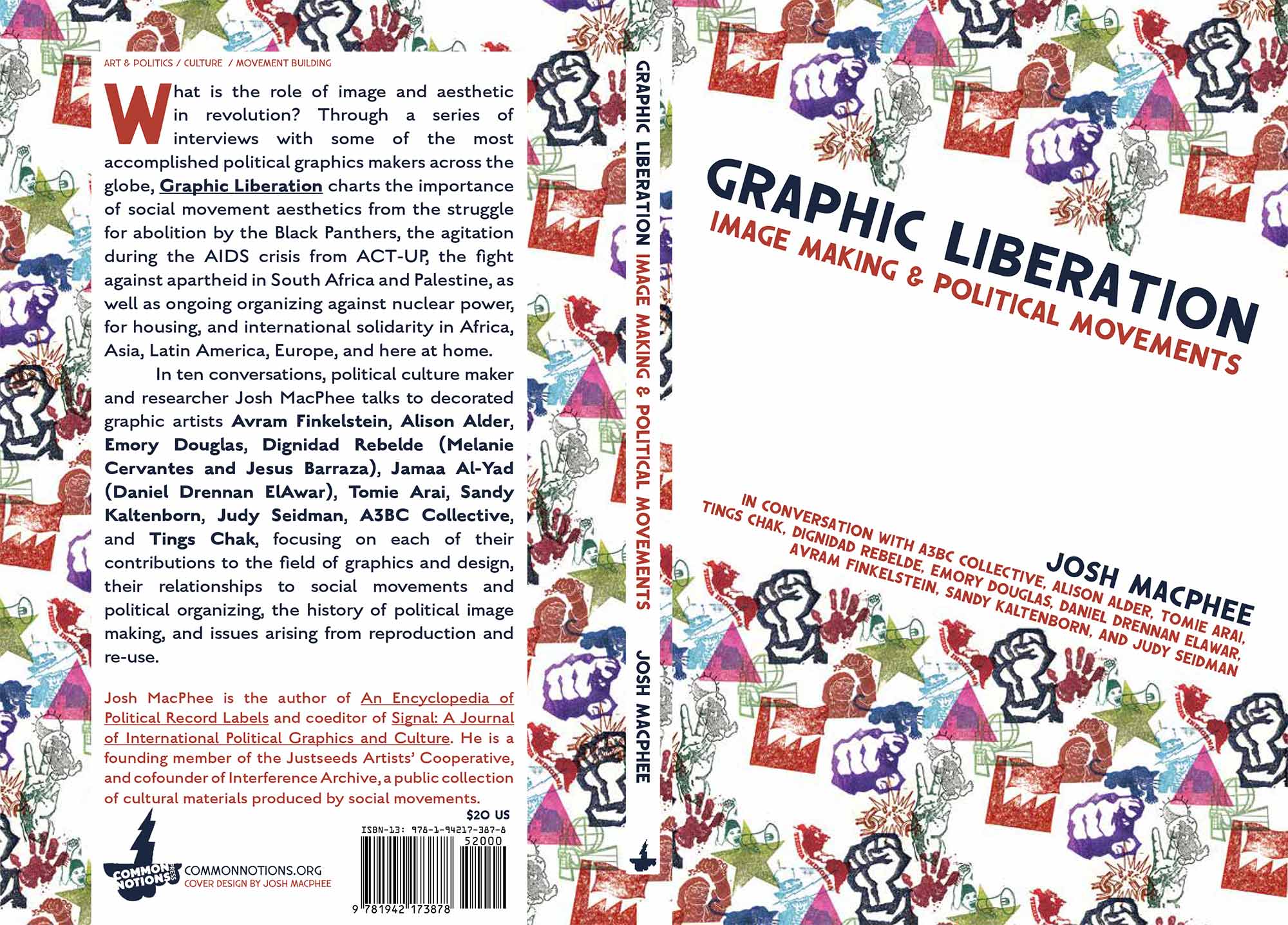

The conversation series provided voices and content to a largely closed campus, but also helped me build a conceptual structure around an interlocking set of ideas: how cultural producers work within social movements; how authorship—and therefore intellectual property and copyright—functions in these contexts; the centrality of collaboration and collectivity with other producers, audience, and both; and how imagery and ideas evolve and jump from one political context to another. Each of these concepts was further addressed in an exhibition, also titled Graphic Liberation, I assembled at Colgate’s Clifford Gallery in the fall of 2021. Iterations of that exhibition then traveled to both George Mason University in Northern Virginia, the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA), and Russell Sage College in Albany, NY in 2022. Both George Mason and CIA were kind enough to each facilitate one of these conversations, so eight were hosted by Colgate, while Sandy Kaltenborn’s was organized with George Mason and Tings Chak’s with CIA.

. . .

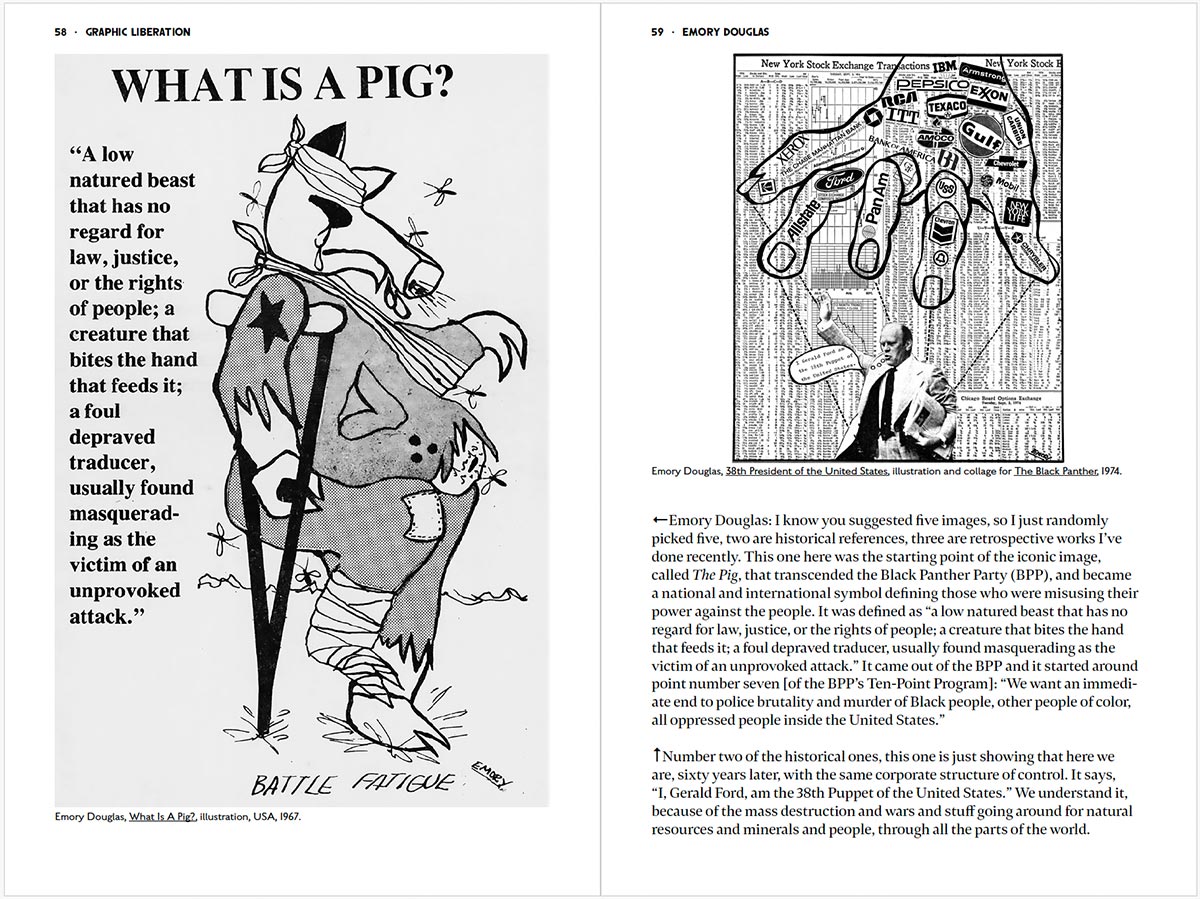

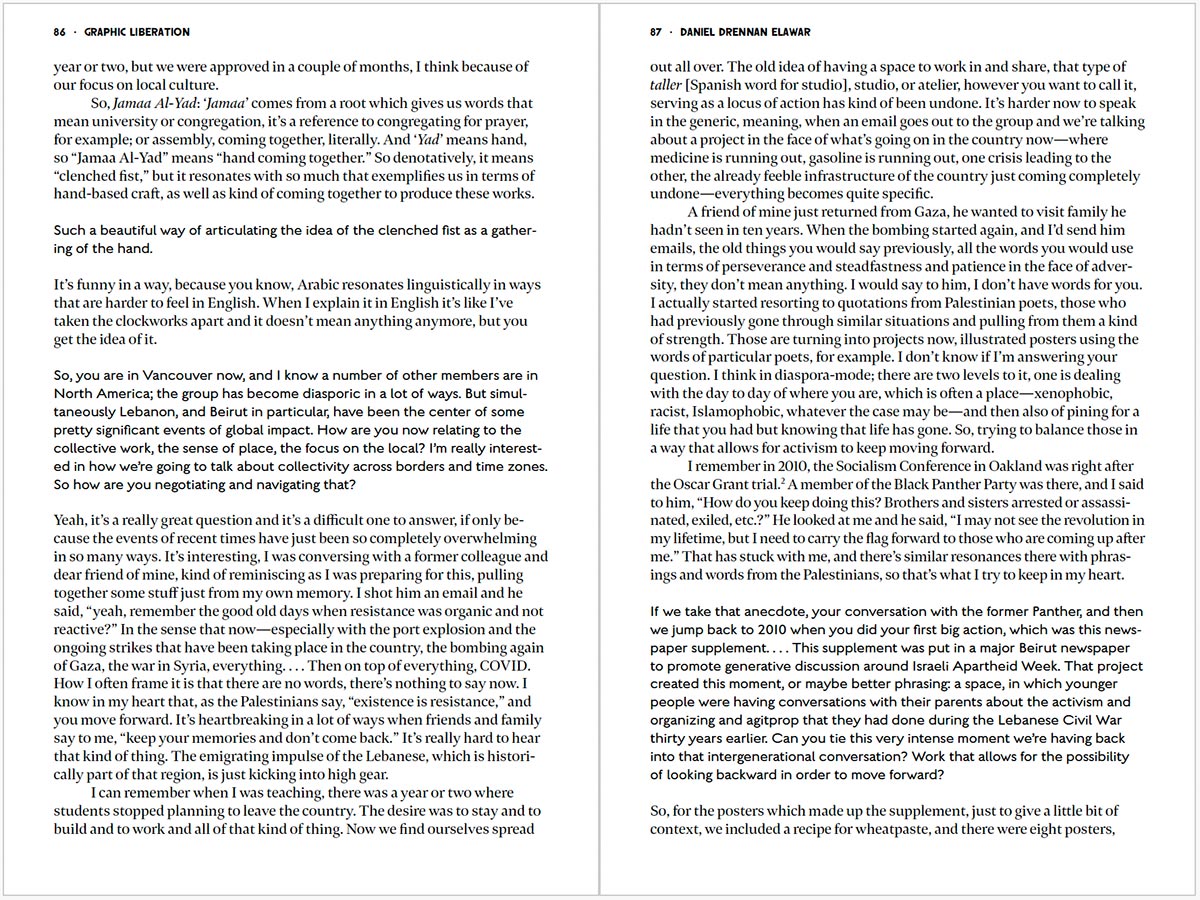

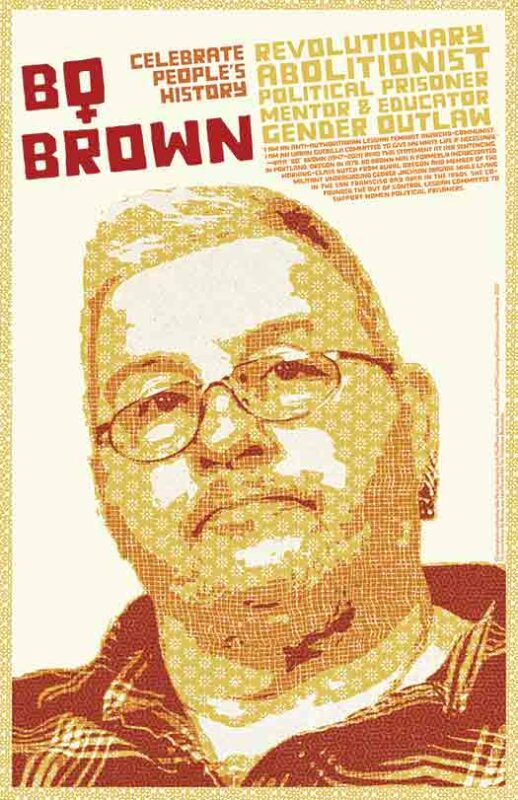

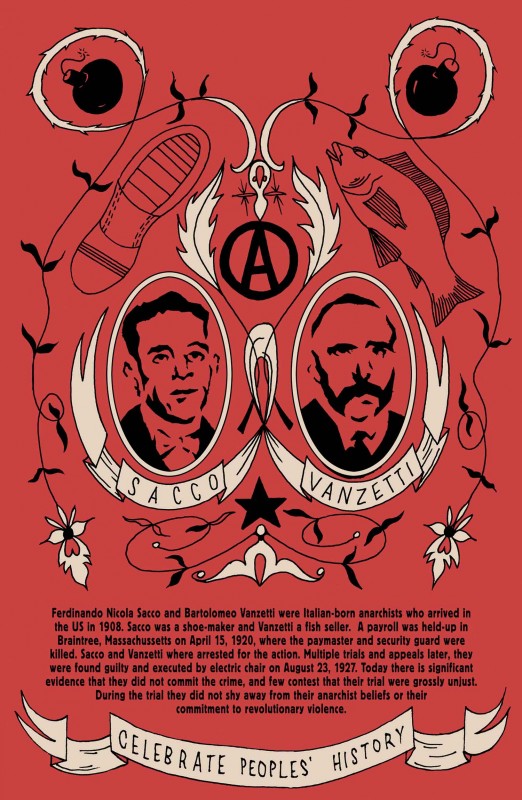

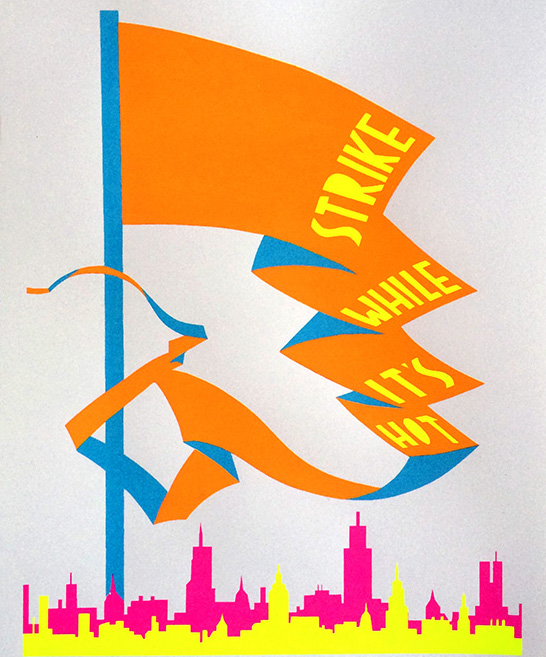

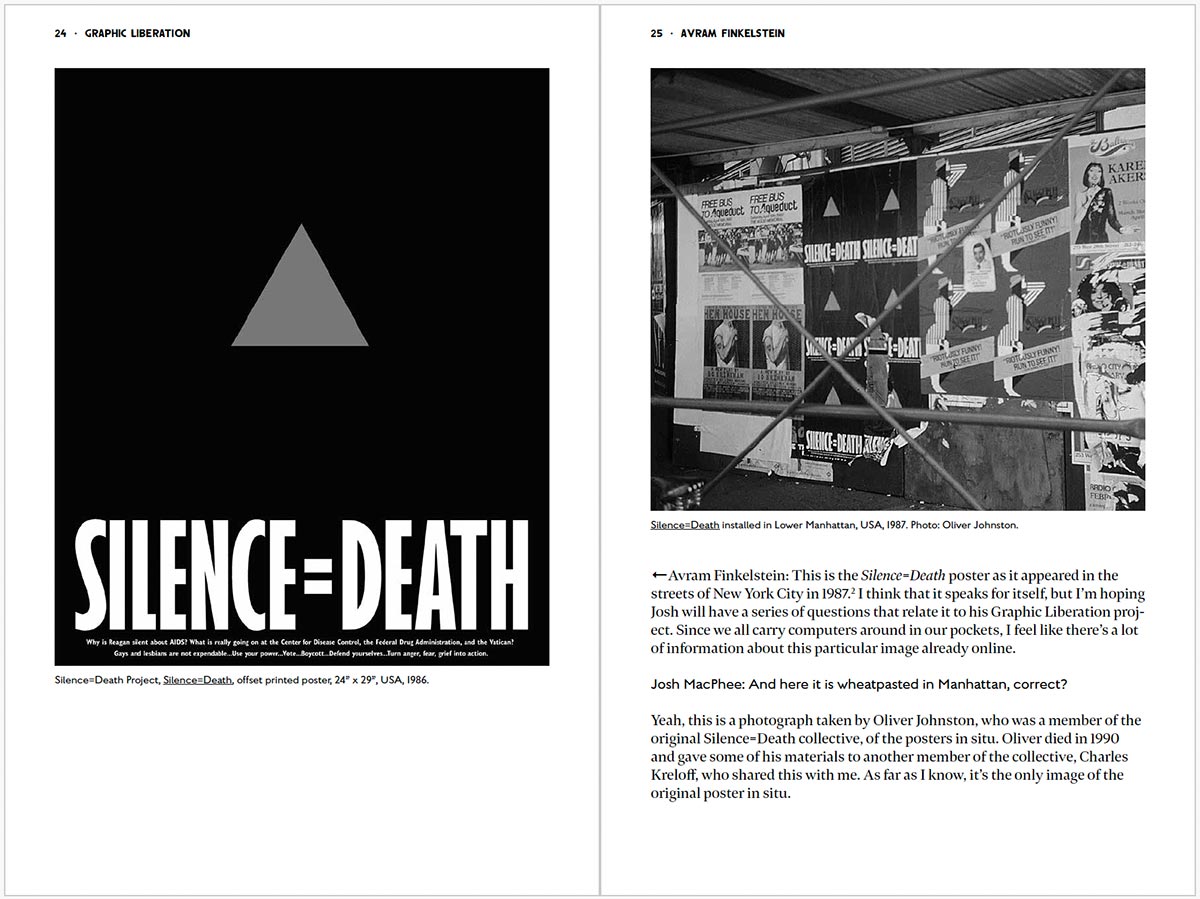

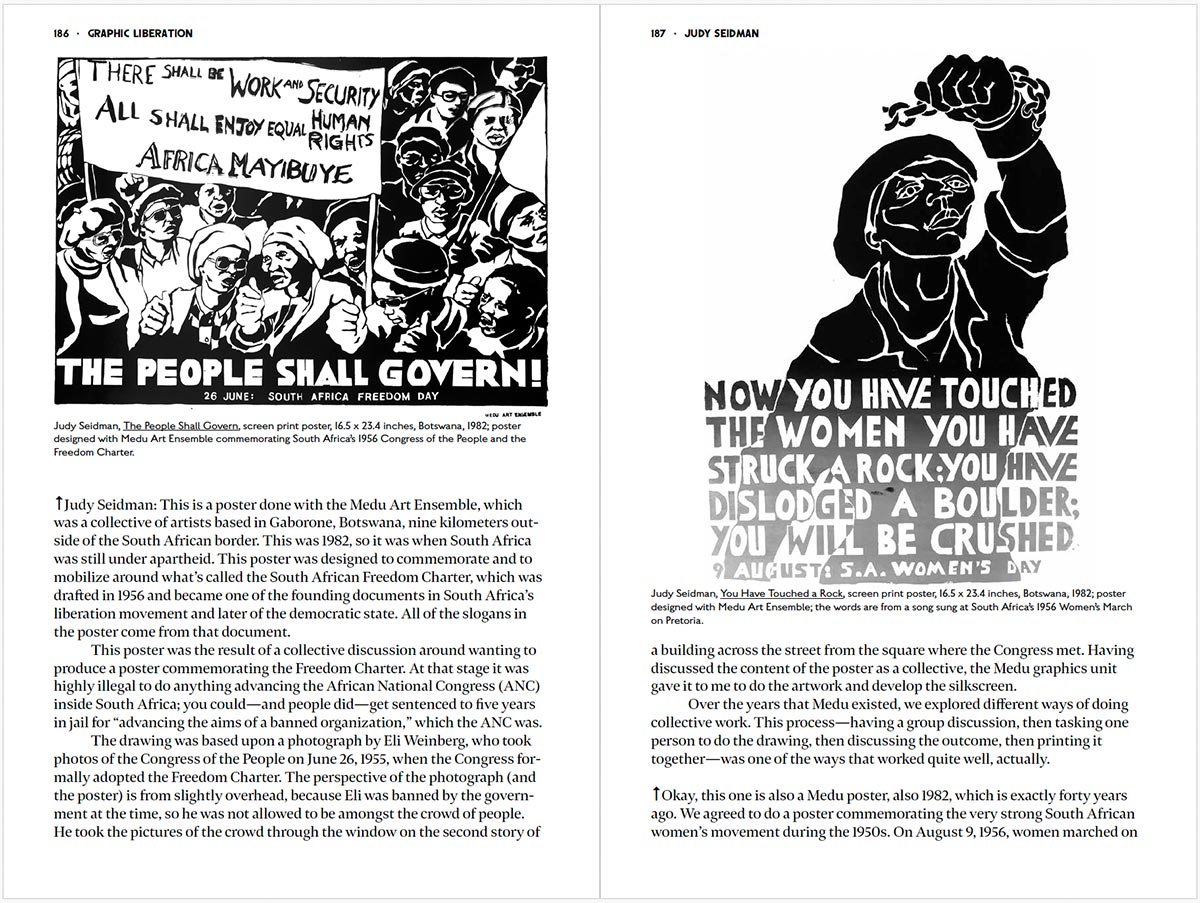

You’ll notice there aren’t many images in this book. For the live (online) discussions, I didn’t want my conversants leaning on prepared presentations about their work, but instead focusing on being present in the moment. At the same time, I wanted the audience to have some grounding in their work, so I hit upon a compromise: each conversation would begin with 4 to 5 images of work, which each person could briefly describe. This created a scaffold for the following discussion to build on. This book is organized in the same manner, each chapter starting with a series of images and descriptions of them and their context, which then open out into a much more free-ranging back and forth. The chapters here are drawn from the live conversations, but are not beholden to them. The transcripts have been heavily edited—and even sometimes added to—by myself, the conversants, and the editing team at Common Notions. The goal here was not to stay true to the live conversations, but to create free-standing discussions that are easy to read and highlight the insights and experiences revealed within them.

Each conversation captured in this book helped me further understand not only how culture has been mobilized for social transformation, but opened windows into ways to build on that foundation. A3BC’s experience of making the entire process of image making collective and collaborative points us in one exciting direction. Tomie Arai’s work with the Chinatown Art Brigade and Sandy Kaltenborn’s subsuming of his design practice into tenant organizing are two others. Melanie and Jesus’s conversion of their living space during the pandemic into a print studio, mobilizing new technologies towards political cultural production, highlights for me how even under the most isolating of conditions we can push forward. Both Avram Finkelstein’s (and Gran Fury’s) and Judy Seidman’s (and Medu Arts Ensemble’s) commitment to their legacy of movement work being held in the commons helps us chart a path away from individual ownership of culture. While everyone in this book spoke to an essential connection to larger communities, Emory Douglas and Alison Alder—in different ways—highlighted how important that connection is not just for the artist but for the work itself, to gain traction and find life as an expression of larger social realities, not simply individual perspectives. Daniel Drennan ElAwar spoke eloquently about how cultural production can help us make intergenerational struggle visible, and how communities are not simply constructed in space, but also in time. Finally, Tings Chak’s work connecting movement artists and designers across broad geographies and experiences points us towards the value of seeing both our similarities and differences. I very much look forward to the “Movement Culture International” that our conversation evokes!

And to be clear, there is also much contention and difference captured here as well. Emory, Judy, Tomie, A3BC, and Avram (really, everyone in this book!) would more than likely have a hearty and conflictual conversation amongst themselves about copyright, authorship, and the control of image usage. Meanwhile I suspect Tings and Sandy might hold some deep seated disagreements about the use of communist tropes in images intended for organizing. I don’t believe there is a simple right and wrong on any of these issues, our relationship to them will always be contingent on our context and what we are attempting to accomplish. Which brings us back to those epigraphs I began with. What do we do when the master’s tools won’t dismantle his house, but these same tools will always be the raw materials at our disposal to fashion our weapons? If anything, social movement culture is rooted in both its dynamism and its tradition. We must grasp both if we have any hope of culture playing a meaningful role in ending the world we know, and building a new one.”

Thanks for reading, and please buy a copy of the book HERE!

Any thoughts and comments are welcome below!