Libre Gutierrez interviewed by Tyce Vande Berg, December 2024

Transportapueblos, Companion of Migrants (images courtesy Libre Gutierrez)

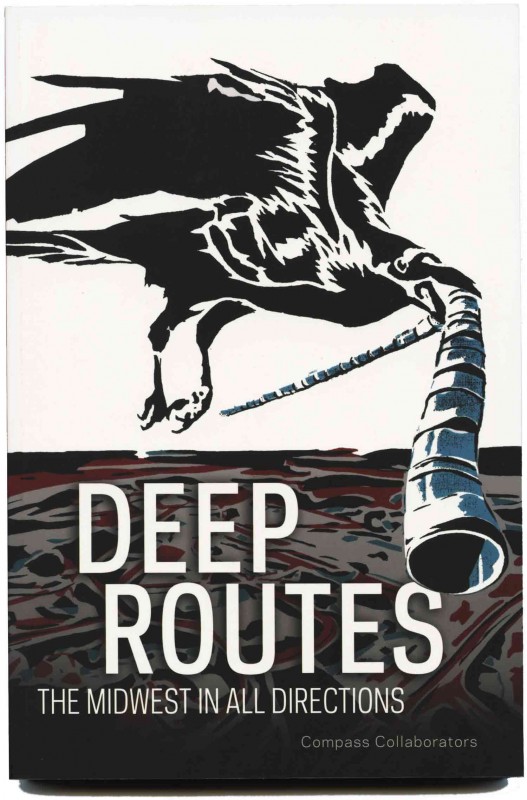

Libre Gutierrez is a sculptor, muralist, and community activist born in Tijuana, Mexico currently residing in Mexico City, Mexico. A large majority of his work comes from the inspiration and work he has done with community organizations and nonprofits over the past two decades. One of his most notable works is the ‘Transportapueblos’ series of sculptures. These sculptures are a lifesaving tool for migrants coming from South America, Central America, and other parts of the world looking to escape violence, political repression, and climate destruction. Supplied with food, water, and information, these sculptures act as a life saving device and symbol of strength and resilience. In this interview, we discuss the idea, creation, and ideas that Transportapueblos represent, as well as what it means to be an artist and how we can prioritize supporting the community around us.

TVB: I am inspired by your Transportapueblos project not only because of the technicality and construction and how beautiful it was, but also how it became a tool. I wanted to ask; did you know that it would become a lifesaving piece?

LG: Well, in a way it was born with that in mind, that was the initial concept, because it came about when I was doing volunteer work. I think it is very important as an artist to do that. I believe that at least here in Mexico, we have a big heritage of art and murals in the history of Mexico, it has always been manifestations of art and sculpture and murals. We have a deep heritage that we should share, and that if every artist donated a day, in any situation, it could be in a jail, in a homeless shelter, could be in a migrant shelter, could be anywhere, this country would be a different thing. With that in mind, I do a lot of volunteer work. At that point I had been going to a migrant shelter for a couple of years in a migrant shelter in Mexico City. I invited them every Sunday, I would take them to museums or the zoo, museums and zoos in Mexico are free on Sundays. We went there a few times to draw animals, because they came from the trip from the south of Mexico. People from Honduras, Cuba, from El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, being violentados, people being treated in a violent way. From the whole route, once they arrive to Mexico in the shelter, they don’t even want to go out. They’re shocked from the whole trip that they just went on. So, me as an artist, working with them, painting with them, and volunteering with them, we would take these trips, it was very mentally healthy. After that, I would buy them coffee or lunch and we started talking every time. I always asked the migrants, what was one of the difficult things besides the gangsters, cartels, the migration and the police. They told me that they didn’t know that there were shelters like the one they were staying in, like Casa Tochan, they didn’t know there were places like that in Mexico. So, I started investigating, and it turns out, at that point, there existed eighty four shelters in the entire country of Mexico that help migrants, that gave them food, water, medicine, care, information. A lot of them proposed different things, these ideas help the migrants. But they didn’t know this, so I thought, well this is important information that they need to know. So, I asked them, “do you think if I do a sign and I write down the shelters that exist and the map of Mexico, it will help them?” They said yes, that would be a life saver. So, in the beginning it became an idea as a sign, but I thought, “that’s too boring, come on, I’m an artist!” So, I’ve always wanted to do a sculpture, because I’m an architect, I started painting and doing murals but that’s always been my dream, doing sculptures. I took that opportunity to do it.

The first Transportapueblos turned out pretty ugly because I didn’t know how to do it well yet, but the intent was the important thing. So, the second one turned out better, and the third one was way nicer. At that point, I learned how to weld. The first one was made from wood, and they destroyed it, people that kidnap migrants. I put it on the railroad tracks and way on the outskirts of the city, in a dangerous, sketchy part, so we installed it in the morning, when all the bad guys were sleeping. At about 7AM. Also, I didn’t ask for any permit because it’s in a legal Mexican limbo where the state, federal and city government don’t give permission. There’s like a limbo where I said, “you know what? It’s too difficult,” so I didn’t ask for permission and just went out with my friends and a floor plan. We marked them and started digging the foundation and poured the cement and placed the metal structure. We would arrive the next day and mount everything, it’s in seven pieces, the legs, the body, the head, and the tail. In about forty-five minutes we were out of there, it’s all wood, and screws so I’d take my drill and *chk chk chk* get out of there. In the end, nobody says anything because it’s cool, the sculpture looks cool, and people start to get attached to it. The tail has shelves and every two weeks, we would take canned food, clothing, things that I bought, or volunteers bought to give to the sculpture. A few times we arrived; people were there with notebooks writing down the geography. If your geography is off, mine is as well, when you think of it, people sometimes won’t know if they’ll arrive in L.A. or Texas, or whatever state in the U.S., or even Mexico. It’s not their country, they don’t know what city borders San Diego, or what state they’re in. I had to learn all of that in the beginning, small towns like, Brownsville or Eagle Pass, I didn’t know these places existed. It was a learning experience. I always wanted to help people with information, it’s all on the internet, it’s there for you, but not for someone who has been robbed or doesn’t have a cellphone, or doesn’t know anyone anywhere in the middle of nowhere and they just bump into that sculpture and it’s like, “Hey, I don’t know you but I care about you, we’re here to help.” In my small way, but it’s my contribution.

Something that really struck me was a message a guy wrote on the sculpture, “I’m looking for Guadalupe from Nicaragua, my phone number is this, your uncle” and his full name. We always write messages on it like, “we’re here to help” or “transpuertapueblos” or “brother migrant.” Then people started writing on it, searching for their family members, writing down numbers, or asking questions. It hit me, it went way over me, the piece was having its own life and path. For me that was a little overwhelming and beautiful.

TVB: That is beautiful. So, would you say that Transpuertapueblos was your introduction to sculpture and maybe even art activism?

LG: No, no, I had been doing volunteer work for years, since 2002-2003. I’ve been doing community work, and I believe it’s activism to educate people in poor areas. To go and try to motivate people and work with them, I’ve been doing that forever. I gave workshops for a ton of years before I got paid. I’m thinking up another sculpture that cleans water where people can grab water from the rain. I’ve been doing different things, different murals, talking about the subject of migration. I had done small format sculptures, but Transpuertapueblos was the biggest one. The concept comes from the idea, that you travel with your town, your music, your colors, your food, with everything. I’ve been a migrant also, staying in places for a long time and you have to adapt, and you bring your culture it’s a beautiful exchange, the knowledge and growth. I don’t know why people are so against migration, we are granddaughters, grandsons, and grandchildren of migration. It’s the way we grow, exchange knowledge, and how we become better. That’s where it came from, you transport your things. I had been painting that piece for years (the coyote), my character. So, when I came up with the idea, I decided to go with the coyote, it was about time. I made it in SketchUp and made it with recycled wood, recycled floorboards. I didn’t have any money at that point, so I had to do it with whatever I had.

TVB: About how many of the Transpuertopueblos did you build? You said one even got destroyed. Did they face any other issues from the government or the state or the city, or from vagrants?

LG: All of them, the one I did in the beginning got damaged. I put the sculpture up and about a year and a half after, we arrived and it looked like someone took some jackhammers to it, there was wood all over the place, the head was mostly intact, but the rest of the body was torn. I was really upset, so I took it to my studio to rebuild it. A friend lent me a warehouse to work on it because it was too big to put in my house. So, I restored it and even put some pieces of metal on the inside, I didn’t know how to weld at this time, so it was just wired and screws. It came out better and bigger, we installed it the same way. It lasted maybe six months, I arrived, and it was just the head, everything had disappeared. It was like a message; I got super upset and packed it up. That’s when I started welding. I thought, I could do two things, “I could stop the project and throw in the towel or say fuck it and buy a welding machine and learn how to weld it to make it stronger” like the three little pigs. So, I said, “you’re not gonna defeat me,” I bought the welding machine and learned how to weld in the next week.

The next sculptures came with metal and things got interesting. I could make them stronger. I did one in Carretero, another one in Tapachula, the border from Guatemala and Mexico. There I had already hopped on La Bestia and had that experience. So, in Tapachula, I made the sculpture of the mother and son, because I saw that experience, I saw families on this journey. Old ladies, people in wheelchairs, traveling in the caravan. Six-hundred fifty people in total. When they commissioned me to do that sculpture, I wanted to do something different. Each one is different. The one in Carretero was white, El Transpuetapueblos Albino. I did one in L.A. with information for migrants that are already there, having difficulties finding help. Also, the American Dream is no longer the dream. A lot of migrants are staying in Mexico. A lot of them end up homeless thinking they’re going into a gold rush. We see it a lot, a lot of migrants coming from the states to Tijuana. For me the Transpuertapueblos piece is a proposal as a human being to help another human being. I think it’s really important, but I criticize my country, the city, my situation, and the world but I also propose ways that we can help one another. I was in a Canadian documentary once and there were a lot of artists from around the world feature, you know, dancers, performers, and this couple who did paste-ups. I was at the end and the director went up to me and said, “you’re the only one who talks about an issue but proposes something to help.” It’s easy for artists to talk about it, but they don’t propose shit.

TVB: It’s half the work. You’re right, I think most artists lean towards criticism and critique, rather than concrete solutions.

LG: Exactly or do something! “Hey, the beach is super dirty, let’s do something!” Grab a bag and go clean it! That’s very basic.

TVB: Would you say that kind of mindset came from all the volunteer work you’ve done?

LG: Yes, my family had a big part in it too. My parents did a lot of volunteer work too, my dad would often grab a broom and just sweep the street. He doesn’t care; he wants a clean street. I think it’s the conjunction of a lot of things that have happened in my life. You know, Mexico is really fucked up, Tijuana also, it’s violent, it’s crazy, but it’s also beautiful. It’s up to us to make it either a Heaven or a Hell. I have a saying which translates to English, “It’s not fair to criticize without doing anything.” For me, it’s not worth it, that criticism that comes from someone who isn’t doing anything.

TVB: I want to go back to Transpuertapueblos, you mentioned briefly your character, the coyote with the pueblo on its back. What does the coyote mean to you?

LG: The coyote, the people that smuggle migrants, they snatched the concept of the coyote. For me, part of the volunteer work I did when I was studying architecture, I was going with a tribe in the desert. I saw coyotes when I was with them. Their mythology has a lot of meaning in Mexican mythology, in the Native American mythology also. For me the coyote has a wise connotation, astute, smart, family individual working in patterns. It’s a symbolic creature. I wanted to bring back the nobility and the beauty of the creature instead of the negative connotation that it has now. On migration, that’s the coyote’s nature. It’s a counter-narrative to the current idea of the coyote.

TVB: What advice would you give a young artist who wants to use their art to help the community? It’s a very broad question but I’d like to hear your answer.

LG: Well, I believe first we need to be very emphatic, try to reach out for whatever you can do. If you see a torn down facade, go paint it or just try to make your community better. If you do mosaics, put it up on the street. Go to a school and maybe stay with the kids after school. Engage in doing some volunteer work. I did volunteer work in prisons; I did that for two and a half years. I did that ten years ago. I did that once a week every Wednesday for eight hours. Now, they’ve started getting released, and they’re my assistants now. Six of my students got out, one is a tattoo artist in Toronto now, one is a painter in his seventies, all of them never want to go back to that place and are great citizens now. They’re helping me out as artists. Just do something like that. I was just thinking about what I can do to help out with my skills and talent. I had a theory where art is a great tool for controlling violent behavior and decided to go to the belly of the beast. It was a very important learning experience. It’s gotten me some international awards, one is the Kindle Project and the Other is Mozaik Philanthropy. You don’t apply to them, they look at your work and see if what you do is real. I was shocked because I do the volunteer work out of my heart, and they recognized it. They gave me that award because of all the years I’ve put in and it created a history of doing shit, and that’s important.

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE ARTIST

Visit: Coyote Sculptures in Mexico and US Share Vital Information With Migrants

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/libre_hem/reels/

About the author: Tyce Vande Berg is Milwaukee-based undergraduate art student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The interview was part of his Fall 2024 final project for the class Community Arts II taught by Nicolas Lampert