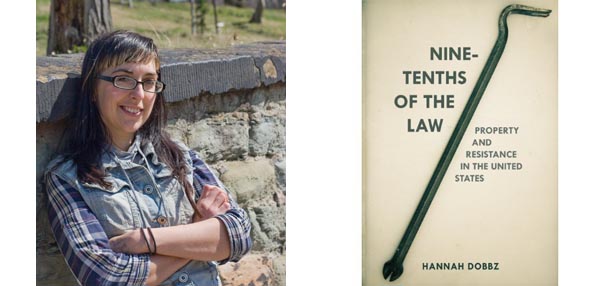

Hannah Dobbz is the Pittsburgh-based author of Nine-Tenths of the Law: Property and Resistance in the United States (AK Press), an effort at framing a new understanding of what it means to own, rent, buy, sell, squat, speculate upon, or simply desire a home here in the U.S. Dobbz digs back through the colonialist history of North America for clues that expose our modern conception of property, dissecting the media spin on markets and bubbles and offering sober and compelling evidence for a resistant re-framing of the current dialog around the housing “crisis” in this country.

I’m not just plugging her new book because Hannah is a long-time friend — it’s actually a damned good read no matter what your current aspirations for “home” might be. You can get copies direct from Hannah here, or from AK Press here. Last month Hannah did an interview with me over email while on tour promoting the book, read more below. She’s also doing some screenings in Worcester and Boston in the next week – those details are at the bottom of the post.

Shaun: Originally I took your research for this book to be specific to squatting in the U.S. Can you talk about how that morphed into a broader analysis of property in the States, the housing market, cooperative living models, etc?

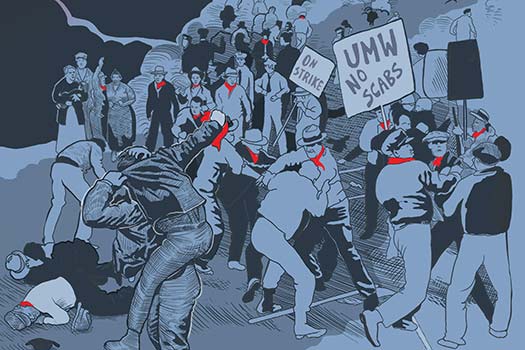

Hannah Dobbz: Squatting is an idea that overlaps with a lot of other ideas, including the ones mentioned above. If I tried to isolate instances of “squatting,” strictly, then I think I would have limited the scope and impact of the book immensely. There are so many types of property resistance—by which I mean challenging dominant assumptions about private property—including rent strikes, eviction defense, foreclosure resistance, and other actions that don’t neatly fit into the category of “squatting.” These ideas, in turn, all prompt so many questions about the very concept of property, and I felt that it deserved some discussion and exploration beyond the simple mention of squatters in America.

SS: You begin your book by framing how concepts of property ownership developed during the westward colonial expansion of Euro-American immigrants, illustrating how contemporary cooperatives and instances of squatting in the U.S. differ fundamentally from the kinds of situations we’re accustomed to hearing about in, for example, Europe (broadly speaking). Can you summarize what the key differences are? In other words, why do American punk tourists in, for example, Denmark, come home disillusioned about realizing the same squatting scenarios at home that they experienced abroad?

HD: Many U.S. squatters feel disillusioned when they have trouble launching European-style squatting movements because they don’t recognize the importance of context. Squatting is a socially rooted action, so the channels and outcomes of squatting in different places will be different depending on those places’ respective social climates. Many places in Europe are known for their rich squatting histories, but they were facilitated by certain cultural climates (and legal circumstances). To try to replicate the squatting outcomes of such European benchmarks, without replicate culture and laws, is a mistake; instead, we need to build off our own history, using the tactic of squatting in a way that fits within the American context.

SS: Can you elaborate a bit on what kind of American-context tactics you see as useful? What kind of Euro-inspired tactics fall flat in the States, and why?

HD: For squatters making a public demonstration: The successful efforts I’ve seen have included a lot of community involvement and consent, taking care to include people from that neighborhood in the action as well in determining if the action should happen at all. Many of the confrontational/militant Euro-style tactics don’t seem to translate in the American context—instead they often seem to just confuse and annoy neighbors, media, and authorities…and then all the squatters go to jail.

For squatters privately establishing and maintaining a home: I have seen it work well to not be too public about the squat but to also avoid sneaking in a suspicious way. Acting normal is pretty key.

SS: What is it about the “fabric” of American assumptions about property that might make squatting (and in a broader sense, cooperative housing, land trusts, rent strikes, etc) seem outlandish to a lot of people? I feel like the gut response of a lot of Americans may be that people who squat (etc) are trying to take advantage of everyone else, that by moving into empty buildings they are exploiting something at the cost of everyone else who is “playing by the rules”. Is that just media spin, or is it a cultural response with historical precedent?

HD: I think that the gut reaction of many people is to think, “Well, I wouldn’t like someone to take over my house,” and that kind of thinking spooks many Americans into clinging to outmoded ideas of property. But it’s a shortsighted view—squatting is not home invasion or theft; squatting can be the mindful re-purposing of genuinely abandoned properties that would otherwise be left to deteriorate and rot. The misunderstanding comes from a myth of scarcity that is inherent in the “fabric of American assumptions about property.” Once we can realize that there is no shortage of these resources (such as housing, which abounds), then maybe we’ll quit this outrageous practice of hoarding properties, enforcing vacancies, razing usable structures, and developing speculative real estate on top of it.

SS: You write about stewardship throughout the book. Can you elaborate on this concept as it relates to squatting in the States?

HD: As a society, we have a habit of defining property ownership as a name on a title, plus the money that was paid for that title. But there is another aspect to ownership that is rarely given credence: stewardship. Beyond capital and title, investment can be demonstrated through property care and maintenance. This is a degree of ownership that can extend to squatters: if a legal owner is nowhere to be found, allowing for a property to become more derelict as time passes, then that person can be called the owner on paper only. In practice, the squatter—or steward—of the property is the one that (presumably) maintains the structure and keeps it from falling down. Because, as a society, we value buildings that are not dilapidated, I would like to see a shift in emphasis from capital investment to stewardship when talking about ownership. It would not only lend legitimacy to squatters in the public eye, but it would also forge pathways to increased preservation of existing structures—rather than triggering further cycles of abandonment when market values drop.

SS: What are some types of property-related activism in the States that you’re excited about right now?

HD: I’m excited about Take Back the Land Rochester creating community land trusts. I’m excited about the new California non-profit Land Action, which helps squatters gain title to their properties. I’m excited about the burgeoning National Lawyers’ Guild network to support squatters legally. I’m really really excited about the squat in Oakland that just won an eviction suit!

“Maybe it’s legally OK, but isn’t it kind of morally yucky?”

Meet with Hannah at these upcoming film screenings in Massachusetts:

Squat or Rot: A Squatter Highlights Reel (3 hrs)

Curated by Hannah Dobbz, author of Nine-Tenths of the Law: Property and Resistance in the United States

$5 suggested donation

This rare collection of footage spotlights squatter struggles around the world and across time. See clips preserved directly from VHS and not available anywhere else. From homesteaders in New York City to rural squatters in Spain, this collection is one of a kind and this screening is guaranteed to be your only opportunity to see it.

The following are benefit screenings to raise seed money to launch SQ Distro, a distribution hub for squatting-related media including books, zines, DVDs, and other ephemera. The distro will be tabling at the event, too, so bring your cash!

July 7, 2013

Doors at 5:30/Screening at 6:00 p.m.

@ The Firehouse

Worcester, MA

July 10, 2013

Screening at 7 p.m.

@ The Lucy Parsons Center

Boston, MA