Justseeds NW (Icky, Pete, and Roger) have been working on a large scale project challenging the building of a Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) pipeline in Oregon. They have teamed up with an environmental organization, BARK, as well as the Indonesian printmaking collective Taring Padi (Roger is over in Indonesia right now! Hi Roger!). It looks like the story has been picked up by The Jakarta Post, which appears to be the English language Indonesian daily paper. A story about the project, “An Artistic Alliance,” was published a couple days back, and you can read it HERE. I’m also embedding it below for those that don’t feel like clicking away from the blog (I know you want to stay…)

An Artistic Alliance

WEEKENDER | Sun, 02/07/2010 3:43 PM | Environment

Artists and environmental activists are working together in a campaign to highlight shared concerns over a proposed massive fuel project. Hana Miller reports.

“There are a lot of Americans who talk about fossil fuels from places ‘that don’t like us very much’,” says Amy Harwood, the program director of BARK, an organization dedicated to the preservation of the forests, waters and wildlife surrounding Mount Hood National Park in the northwestern United States.

Harwood has dedicated much of the past couple of years to a major campaign against several proposed liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and pipelines to be built in the state of Oregon, one of which would travel right across the Mt. Hood area.

In the summer of 2008, Harwood walked the almost 80 kilometers of the proposed pipeline, meeting local residents along the way who faced the most direct risks from the range of economic, environmental and public safety threats that critics say the pipeline poses. What she found among some of the concerned residents was that amid their reasons for opposing the import of foreign LNG, they disapproved of supporting the exporting countries: Iran, Russia, Qatar and Indonesia, among others.

“A lot of people think of Indonesia as a harbor for extremist Muslims,” says Harwood, who has herself had a long fascination with the country’s artistic, cultural and political history, and has enjoyed the process of sharing this fascination with the diverse range of people involved in the campaign.

“I’m excited for the activists here to learn that there are people who live in the exporting countries who are fighting the same industries and sharing similar struggles.”

Harwood is one of a group of artists affiliated with the Justseeds art cooperative in Portland who will be collaborating with artists from Yogyakarta’s Taring Padi art community on an image that will represent the environmental, humanitarian and social concerns of the import and export sides of the LNG story.

Even though the source of the LNG for the proposed pipelines in Oregon has yet to be announced, talk of the project has already been an eye-opener for many people, especially those who had never considered there were people in the export countries fighting the same fight as them.

“Plus it gives me an opportunity to share with them how absolutely wonderful Indonesia is, and that it is not a ‘bad place’,” Harwood says.

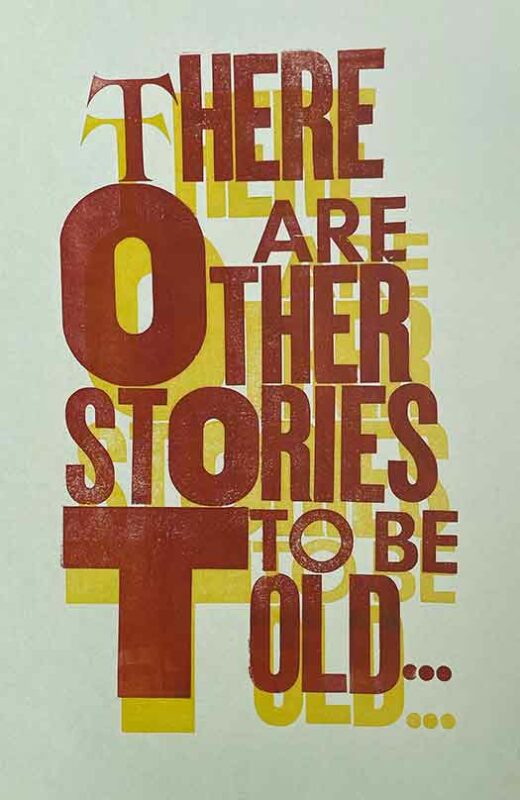

“The idea,” says artist Roger Peet, who came up with the concept through a series of conversations with colleagues, “is for three Justseeds Portland artists to collaborate on a 3-by-1-meter relief print depicting the impact of LNG development on rivers, forests, farmlands and the world [through global warming] on our side of the Pacific, where the gas is consumed, and for Taring Padi artists to depict the impacts of the extractive processes on the other side of the Pacific in the same format, creating a narrative image.”

The project represents another side of the LNG story. It signifies opposition to the financial incentives that power the process by which natural gas from overseas is liquefied and transported in tankers across the ocean, arriving in the United States to be re-gasified and delivered along pipelines to markets. In this case, the pipelines through Oregon, which a Department of Energy report concludes needs no extra LNG, are intended to supply neighboring California, which has banned the pipelines being built within its own state borders.

From the point of view of many Oregon residents, they are the ones who will bear the brunt of the LNG’s environmental impacts, sharing the burden with the countries whence it is sourced.

“The environmental risks of LNG production are enormous,” argues Daniel Serres, conservation director of Columbia Riverkeeper, an organization dedicated to protecting the waters of the Columbia River, on which two of the proposed terminals are to be built.

“LNG production requires huge gas exploration and production, and subsequently this gas must be super-cooled and loaded into enormous tankers for global consumption. The pipeline construction and dredging for LNG export terminals can have severe negative environmental impacts.”

It has been five years since initial plans were proposed for LNG in Oregon, and the opposition to it has spread from local residents in the areas of the proposed pipelines and terminals, as awareness about what it means to be a part of the affected community has grown. Mt. Hood, for instance, supplies the water for a third of the state’s residents, making the environmental impact of the proposed pipeline in that particular area a concern to far more than just its immediate local residents.

“Opposition to these projects spans the entire state and crosses political lines,” says Olivia Schmidt, a prominent spokeswoman and community organizer for the campaign, “making it a bipartisan issue that concerns not only directly impacted communities but also defenders of public lands [also impacted by development], climate activists, property rights proponents, anti-war activists, forest defenders, environmental conservationists and folks working for US energy independence.”

When the far-reaching impacts of imported LNG are fully considered, it is clear there is much at stake: from the clear-cutting that will damage old-growth forest, to the appropriation of private property, much of which is agricultural and will therefore affect not only local food sources but also local economies, to the detrimental step away from carbon-neutral energy development.

However, proponents of LNG use argue it is a lesser evil than other damaging fossil fuels such as coal; it releases less CO2, they contend, and is also relatively safer. For opponents, it comes down to the issues of careless consumption: depletion of the national economy, political conflicts of interest, and deferring the impacts of extraction to places that are out of sight and out of mind. As Schmidt puts it, “Our consumptive habits in the United States are felt by the disenfranchised all over the world.”

In Indonesia, JATAM is a network of local organizations that support communities affected by the work of the mining, oil and gas industries. These people endure the very calamities feared by those living closest to the proposed pipelines and terminals in Oregon.

“In these cases, the people are always on the losing side,” says Hendrik Siregar, who manages JATAM’s Crisis Area Advocacy. “Many people have no idea about the future risks they face.”

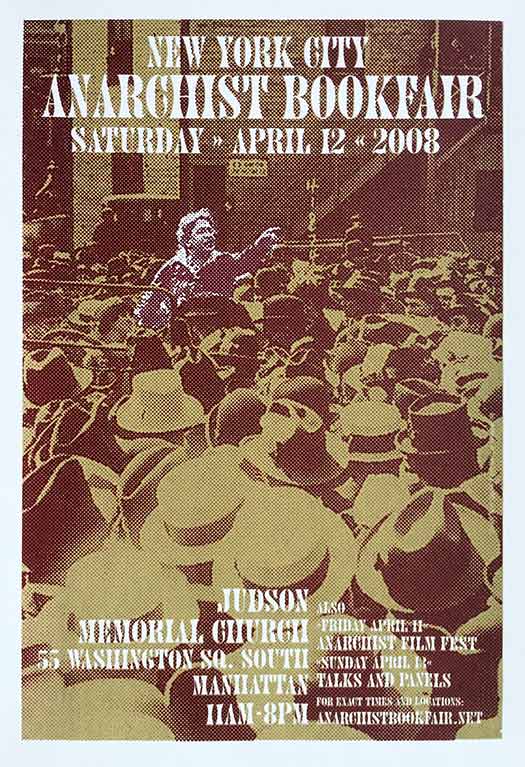

Ever since it formed in 1998, Taring Padi, best known for its political posters representing the voices of the disenfranchised, has generated somewhat of an international buzz among art collectors and activists alike.

“Our goal is to show there are still people fighting against the exploitation of nature, through art that shows awareness,” says Mohammad Yusuf, who has been part of the community since its beginnings. “We hope our art will inspire changes for the better.”

And they seem to have achieved just that. By communicating the issues faced by the Indonesian people to local and international crowds, Taring Padi’s work has created a sense of community that extends beyond geographical and political boundaries, allowing them to be referenced by people like Harwood as she busts myths about the “bad places” that export LNG, as well as inspiring other artists in seemingly faraway lands.

“Taring Padi specifically has been something of an inspiration,” says Peet. “They’ve made some of the most striking political art I’ve ever seen, merging unflinching depictions of the brutalities of power with folk themes and a clear-eyed appraisal of history to synthesize communicative works of uncommon power.”

The collaborated prints, which will be displayed in both countries, are expected to raise awareness for the support of those affected by LNG oversights at both the import and export ends of the industry, as it sets about to demonstrate, both in gesture and form, that it is all part of the same story. In a globalized world, the interconnectedness of countries, people and the environment is inevitable.

“I believe the efforts of Justseeds and Taring Padi will help highlight the global impacts of LNG development and identify the deeper social injustices that result from US dependence on foreign sources of energy,” says Schmidt.

In the meantime, the campaign against LNG in Oregon has pushed the projects back two years from their original schedule, with none of the proposals for construction or operation achieving state-level permission. Though Schmidt reminds those involved that this is by no means a declaration of victory, “Every day that goes by without permits or construction is evidence of our success.”