Founded in 1952, three years after the Communist Revolution, Foreign Languages Press is one of the external propaganda arms of the Chinese Communist Party. They supposedly have published over 30,000 titles in a total of forty-three languages (according to Wikipedia). Their books, booklets, and pamphlets must have been produced in huge numbers, as it is no uncommon to find them kicking around used bookshops, flea markets, and thrift stores. I’ve pulled together a small collection of a dozen titles, and I don’t think I’ve paid more than $4 or $5 for any of them, most them were in $1 bins or a quarter at a yard sale.

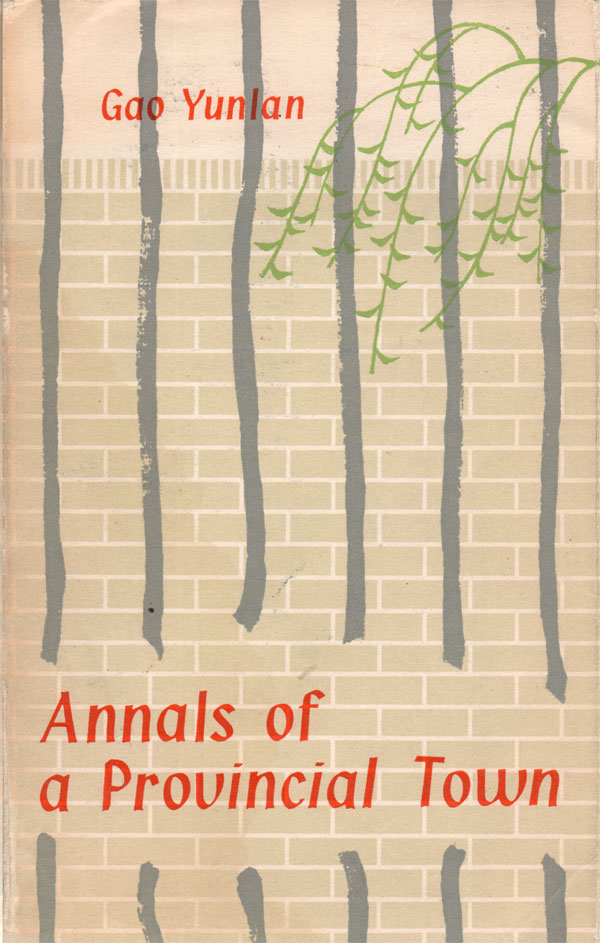

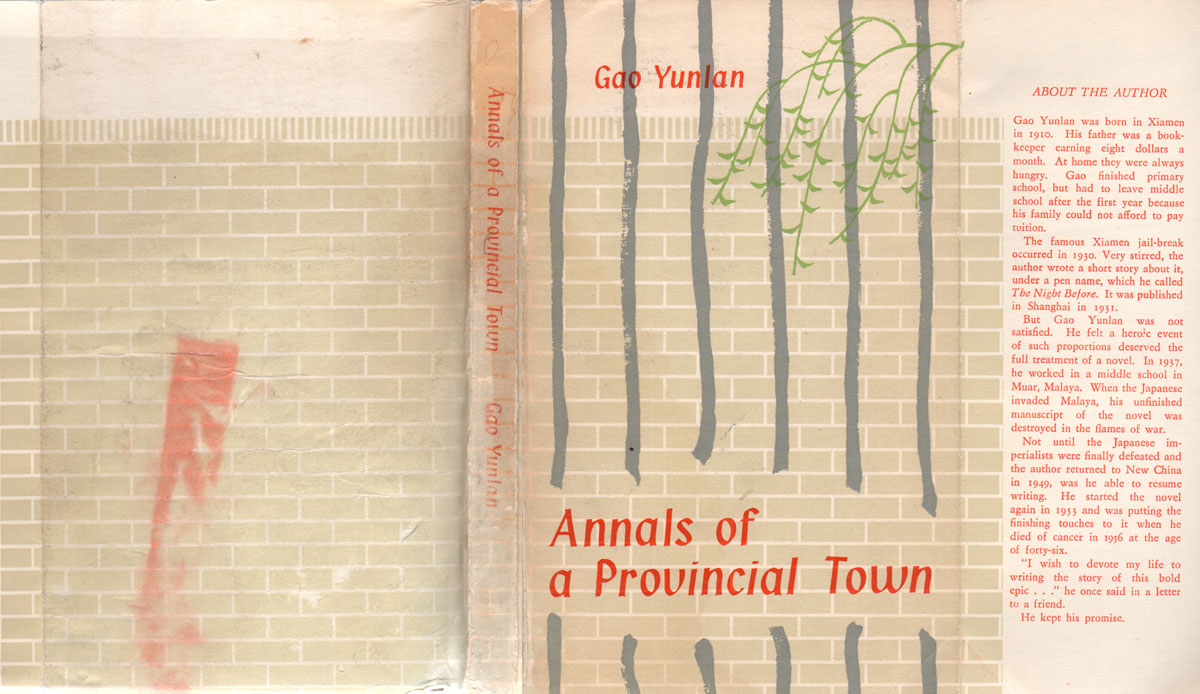

This is some of the most common Communist literature kicking around the U.S., and one of the things that’s really interesting, is that none of seems to have been designed with a clear U.S. audience in mind. The aesthetic and sentiment of all the covers appears deeply part and parcel of the logic of the Chinese government, in a way that seems so much more foreign than most Soviet or Cuban propaganda. Most of the books feature either happy workers/soldiers or a bizarre combination of the pastoral and industrial functioning together, side-by-side. The Gao Yunlan book above is one of the few exceptions, where the cover is more abstract, the narrative of a prison escape illustrated by broken bars and a high brick wall.

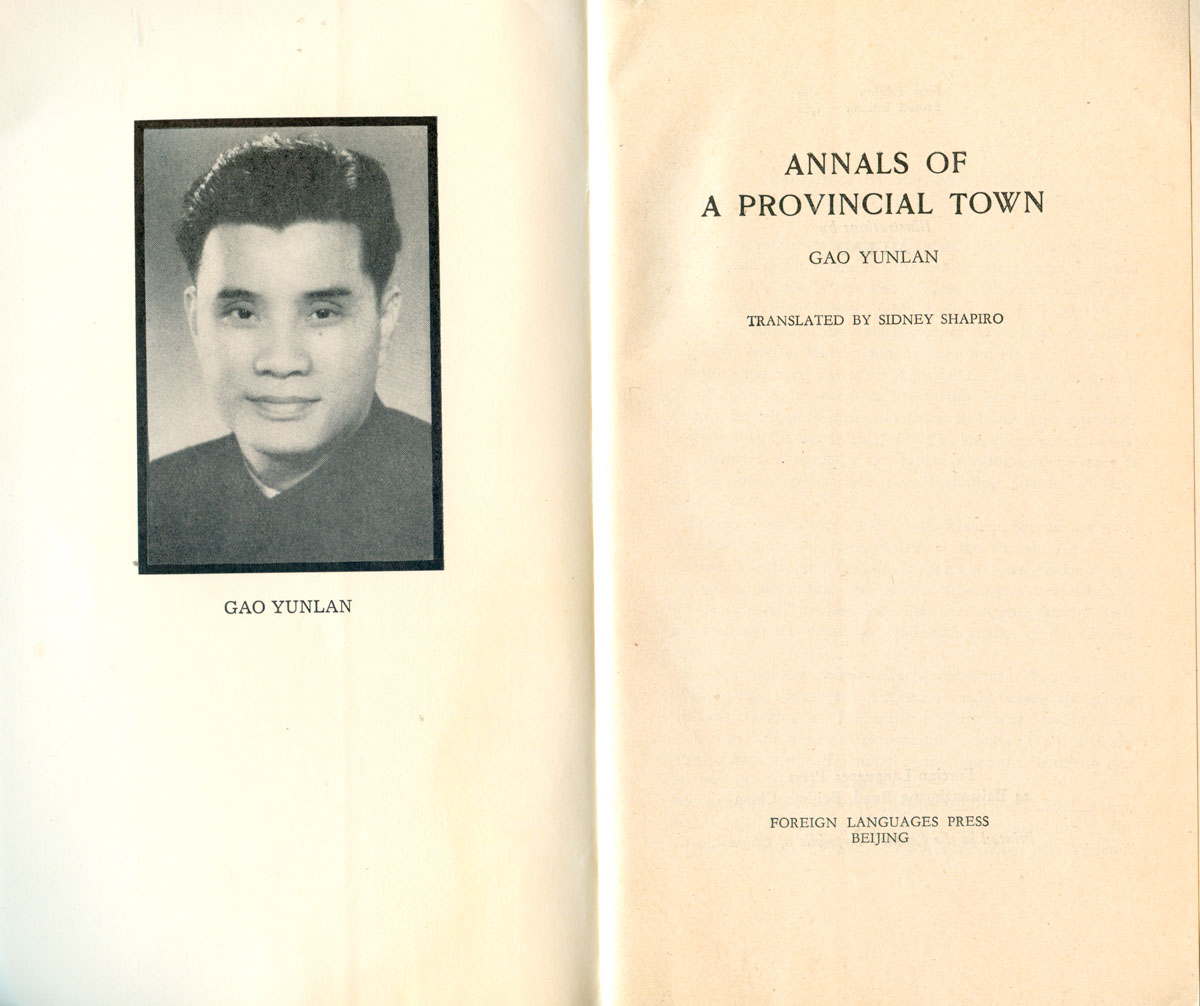

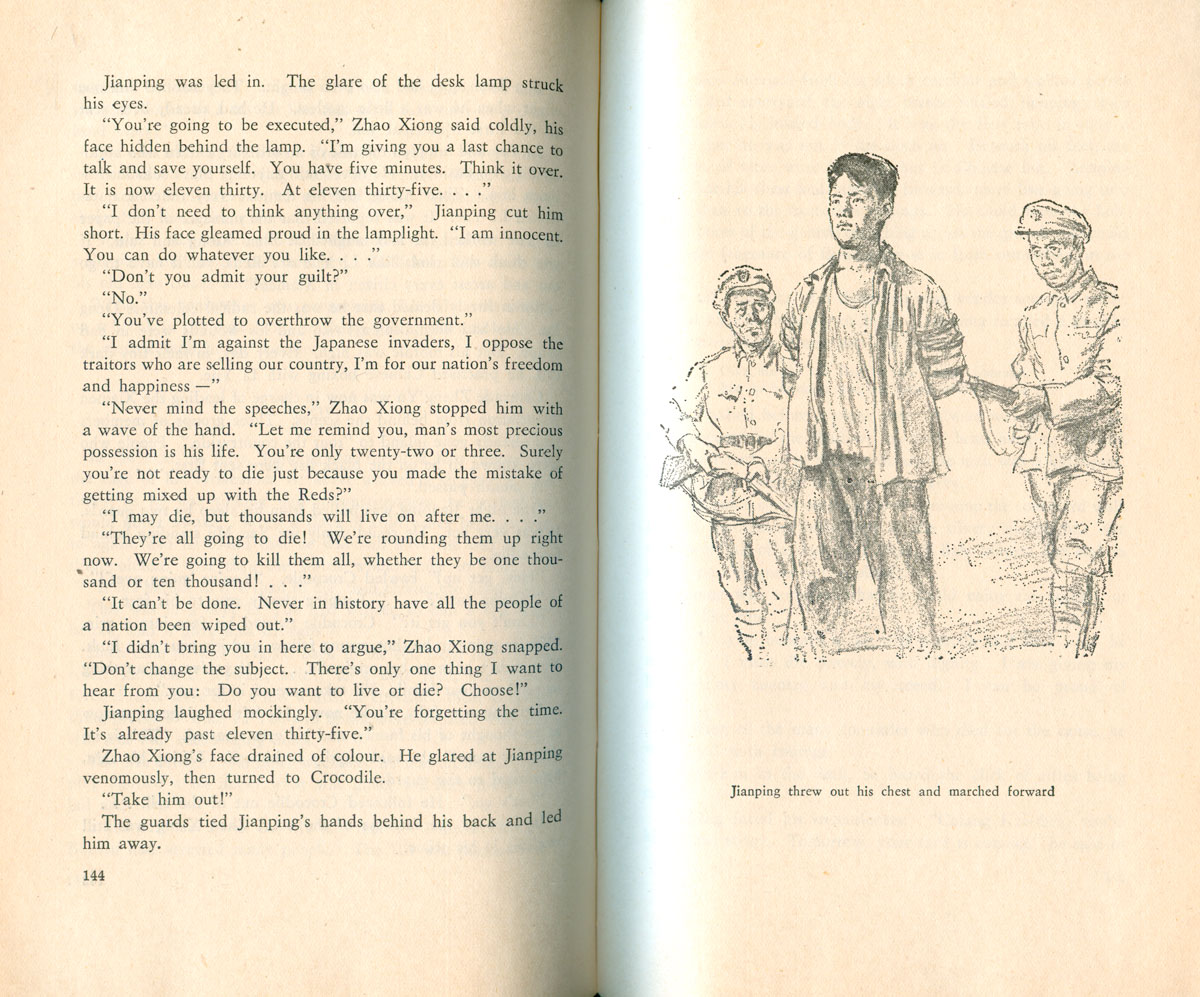

The design and colors are subdued and pleasing, with some nice flourishes like the plant on the front or how the brick wall wraps around to the back. The cover design here, like all the Foreign Languages Press books I’ve seen, is not attributed to a designer, at least not in English. Annals of a Provincial Town is likely one of the few books published by the press to feature a printed portrait (on higher quality paper) of someone other than Mao. The other illustrations inside are attributed to Ah Lao, and are socialist realist with a 1950s vibe.

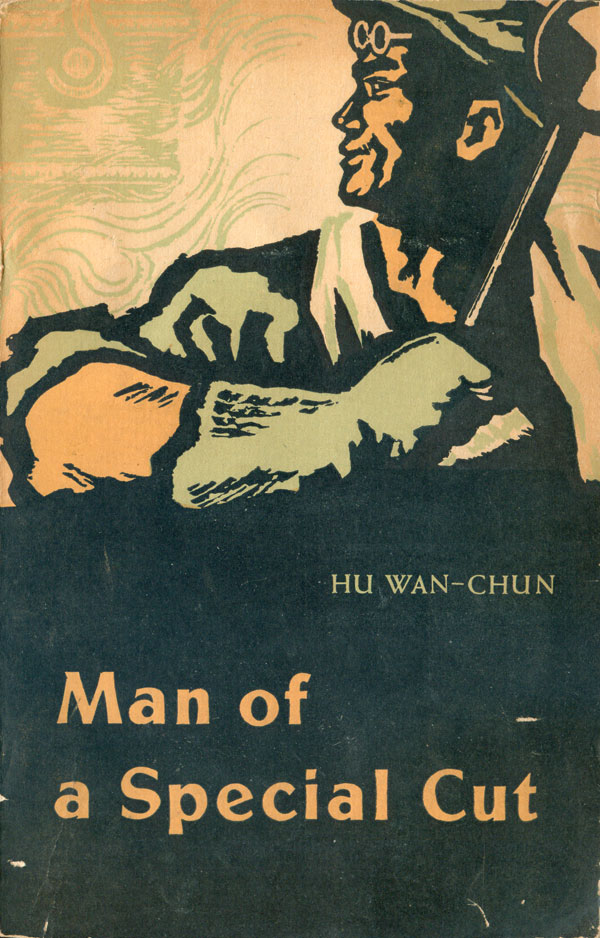

Nope, unfortunately Man of a Special Cut is not gay circumcision porn. It’s Maoist worker-martyr porn instead, “a story of a government cadre who by relying on Party leadership and closely co-operating with the workers, successfully completes the reconstruction of a railway track.” Yes, a real page-tuner!

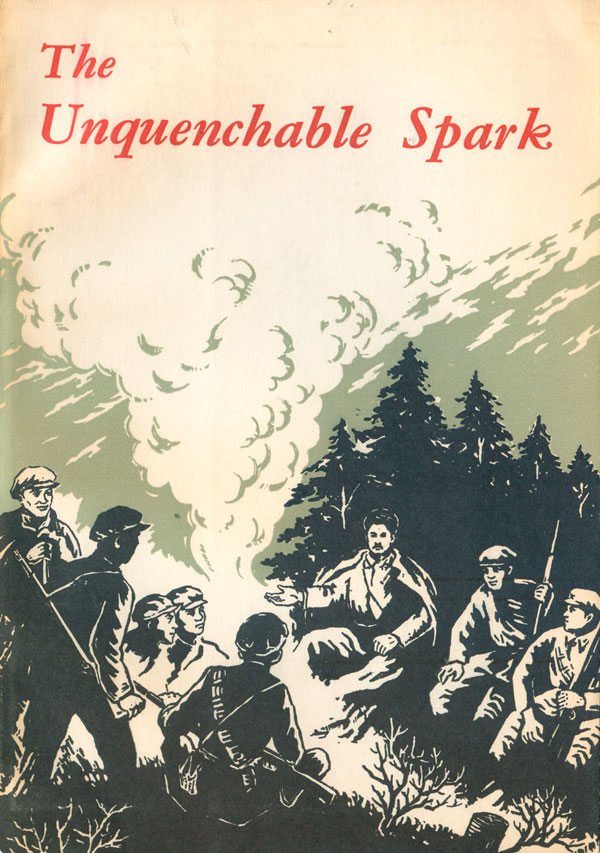

The Unquenchable Spark is a collection of stories about Red Army guerrilla warfare in the mid-1930s. The eponymous “spark” is the one that starts a prairie fire. The partisans on the cover look like a cross between soldiers and hobos, and being that this is about China, no worker or soldier is ever left to their own devices, even around the campfire they must listen to their leader (in the center) pontificate. But it is a nice blockprint, and the smoke opening up for the title is a nice touch, although a stronger font choice could have been chosen. There is something interesting about how the titling on most of these publications is bizarrely understated compared to everything else.

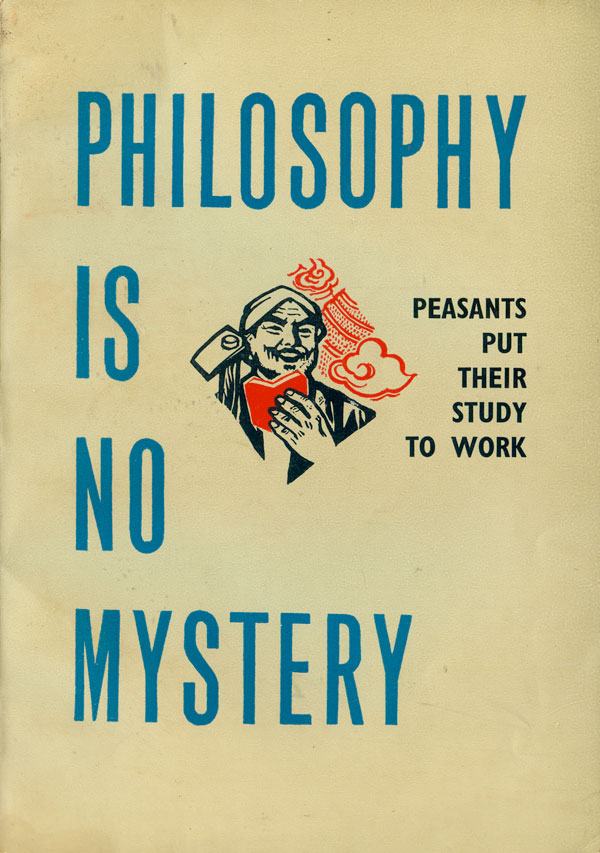

Philosophy is No Mystery has a completely different aesthetic than the other books and booklets. The image of a peasant, smiling with Red Book in hand, is cropped and small, overshadowed by the large, tall type. This pamphlet is neither much earlier nor later than the others, so I’m unsure why the sharp design change.

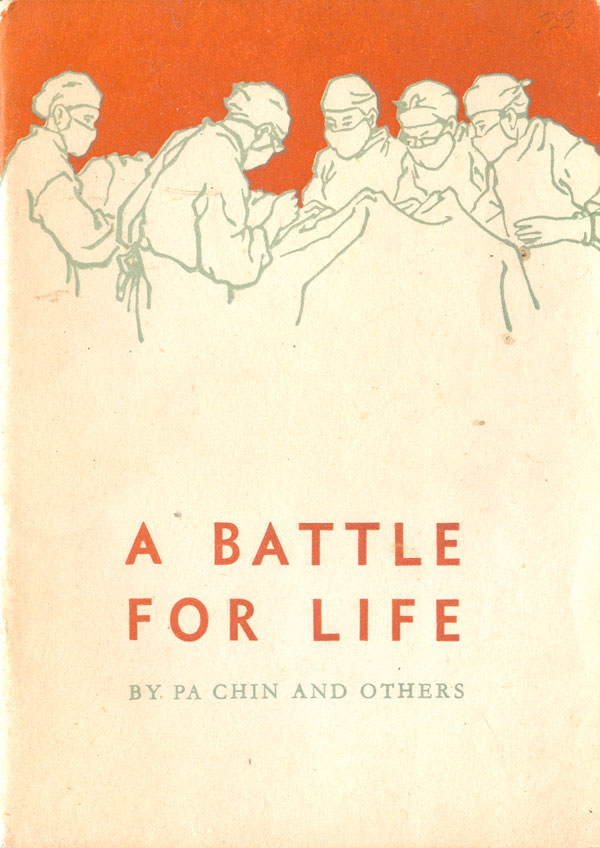

The cover of A Battle for Life is one of my favorites of the lot. The majority of the spacial field is simply the rough, cheap paper the pamphlet was printed on, but the understated design really activates the space. The dark orange background at the top is effectively balanced with the thin sans serif title—center justified in a strong block at the bottom center—which gives weight to the design and anchors the doctors. Pa Chin, the author of Family, was actually an anarchistone of the most well-known in China and one of the few that the Communists didn’t assassinate, in part because of his popularity. It is unclear to me if this pamphlet was written by the same Pa Chin, or another, as the writing seems nothing like the novelistic style of Family.

Although three of the five books this week have named authors, as we’ll see next week, that is not standard for Foreign Languages Press. In the next post will look at another half dozen titles, all anonymous.