I first became sensitized to the problems within the U.S. prison system in the early 1990s. A friend brought me to an event in Washington, DC about the political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal (stay tuned, Judging Books #45 will be entirely dedicated to books by and about Mumia). The event (and Mumia’s case, more generally) was a great introduction to how the U.S. prison systems sit at the intersection of many important issues in out society, in particular race, class, violence, and political engagement, but also gender, health care, sexuality, age discrimination, and much more. Once my eyes were opened to the basic facts (yup, facts, there’s no arguing with them) that the U.S. imprisons more people per capita—by far—than any other developed nation and that percentage-wise the vast majority of those people will be poor and people of color, I started digging around for more info. It turns out that there had been a significant movement to reform/abolish prisons in the 1970s, and a lot of books had come out in the 70s and 80s, but by the mid-80s the Reagan revolution was in full swing, and “tough on crime” was the mantra of most politicians, left, right, and center. For the next couple weeks I’m taking a look at the books from that era that my friends and I were able to track down and read. After that I’ll be looking at the next generation of prison books, which started coming out in the mid-90s and my peers began publishing.

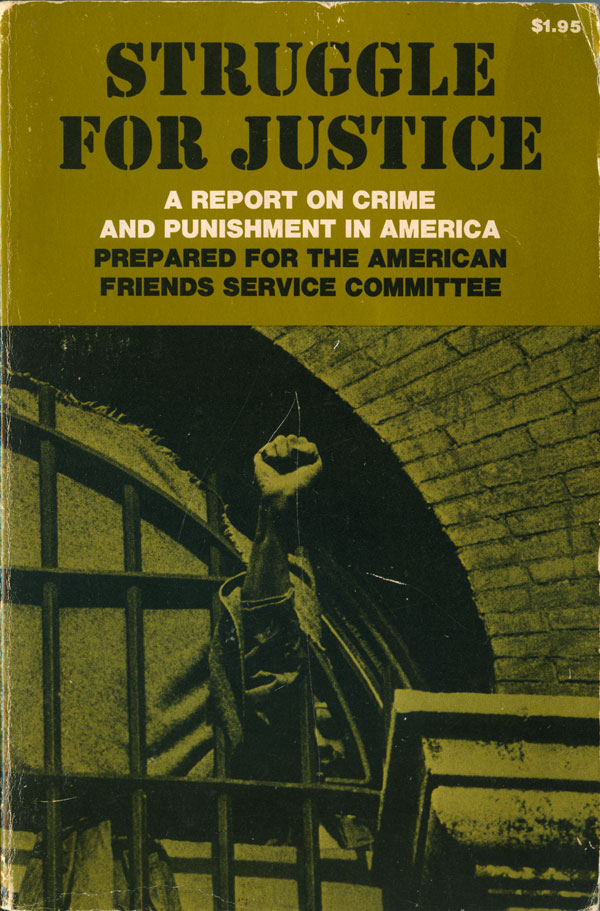

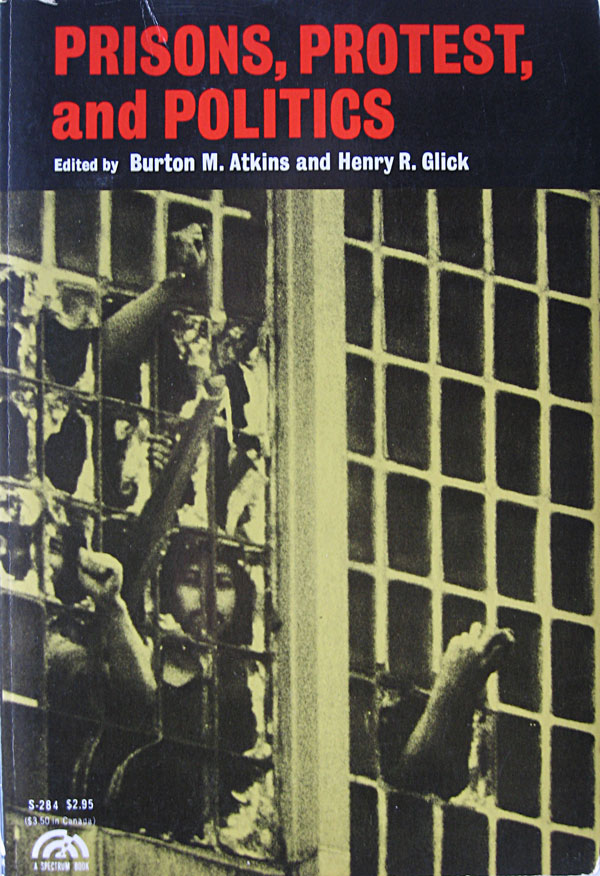

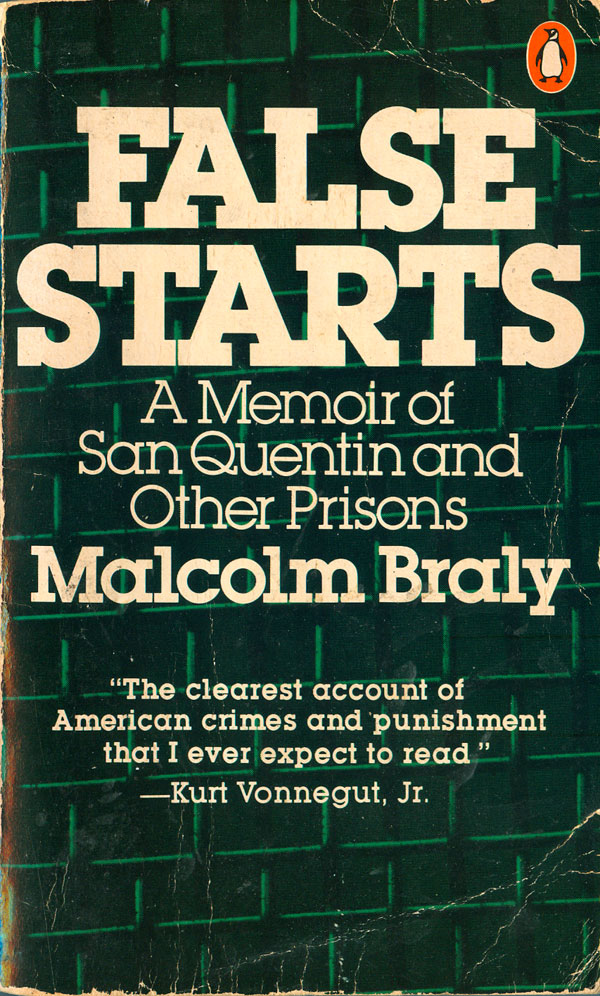

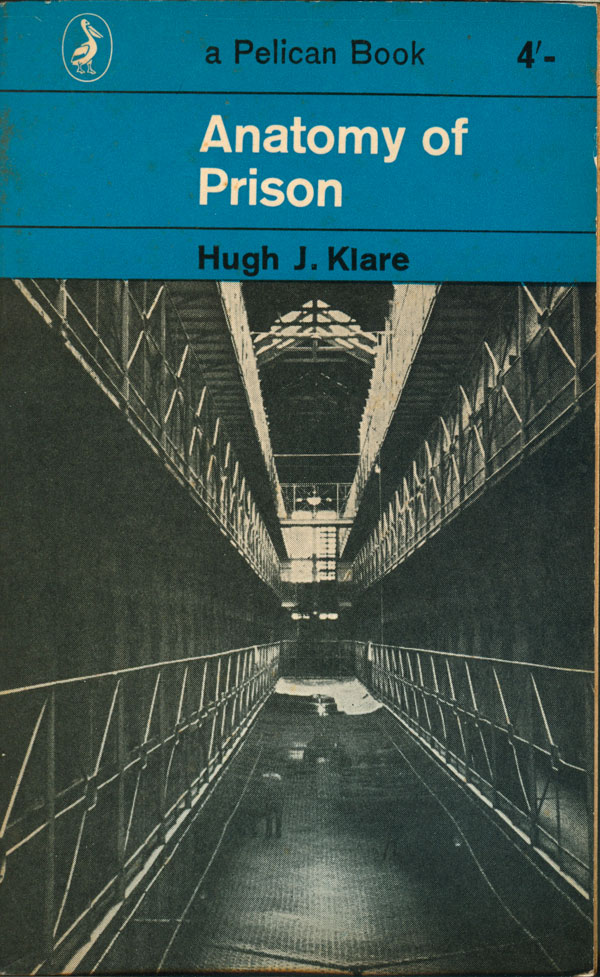

The book above is the oldest of the books I’m looking at, a nice Penguin from 1962 with a great perspective-heavy view inside a prison. Then we jump to the 70s, and most of this crop don’t have the most imaginative of covers. The AFSC report to the left has a nice classic photo of the fist through the bars on a saturated green background. In fact, that image has been reproduced so many times, I can’t even figure out what the source is, possibly from Attica? (Does anyone out there know the source?) Also notice the stencil font for the main title, a recurring type-treatment theme for prison-related titles. The Atkins book to the right uses a similar image of prisoners thrusting fists through bars. This image is less iconic, but more collective, and in that way much more representative of actual prison resistance and protest:

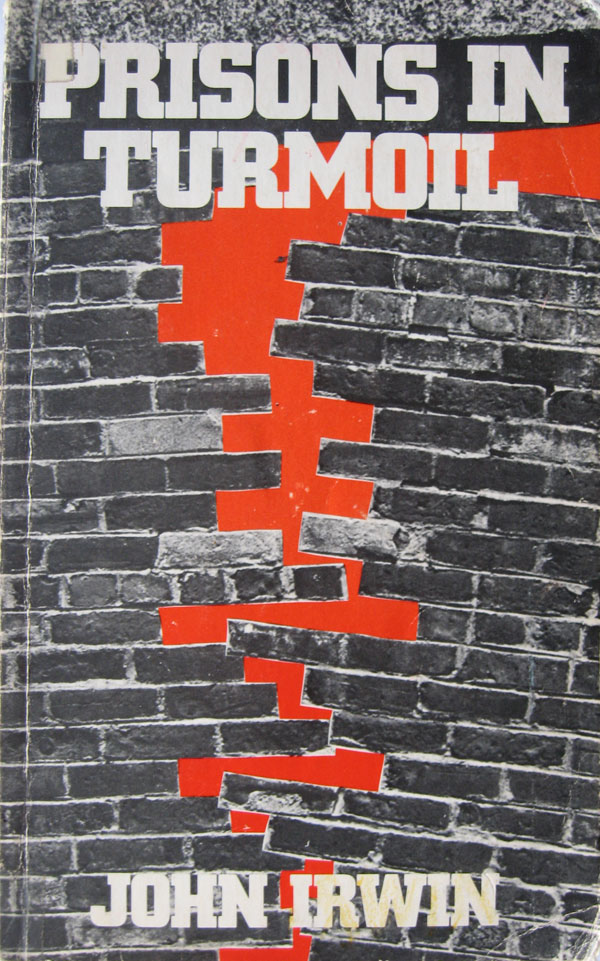

Below to the left we have a tightly woven fence, which at first look passes as a brick wall, and to the right we have an actual brick wall, awkwardly cracking to show a bright orange-ish red inside. I suppose this is to communicate the “turmoil” of the title, but it seems to me the walls of prisons breaking open is just about the best thing that could happen to them, no turmoil there!

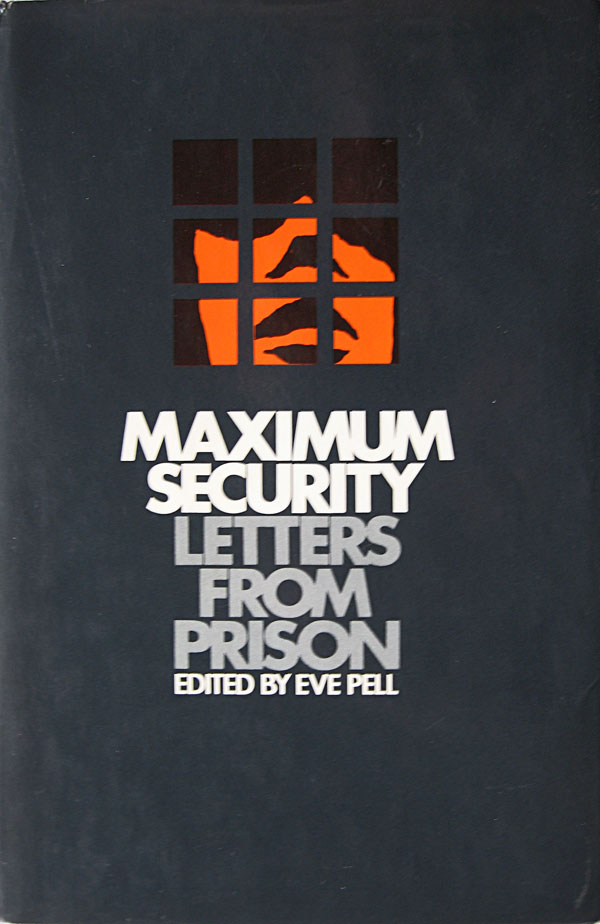

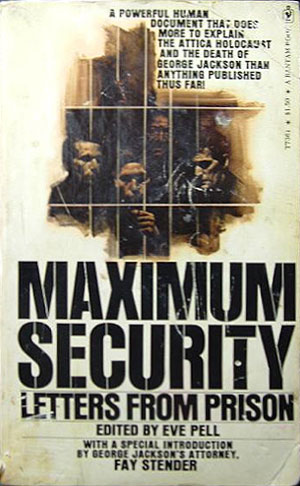

With the rise of the 70s prison movement was an attempt to get the voices of actual prisoners into the mainstream discourse. The book below was one those attempts, and you can see its activist bent by the description of Attica as a “holocaust” and the mention of Black Panther and political prisoner George Jackson. The cover of the hardback (to the left) is a much more effective cover due to its minimal-ness and shrewd use of political signifiers. The face behind the bars is rendered in flat fields of orange and black, and is a clear reference to the popular political printmaking style of movement artists like Rupert Garcia, who produced a poster in support of Angela Davis in the same color scheme. To a general audience the cover evokes a sole body locked within the prison system (or the book!), but to an activist audience it also evokes the repression of the movement by the government, and the massive increase of prisoners from the Black Panthers, Young Lords, and dozens of other political groupings. The paperback to the right is geared to a much broader audience and this more sensational, with bold stencil font title and very 70s painting of med in the shadows of a prison cell.

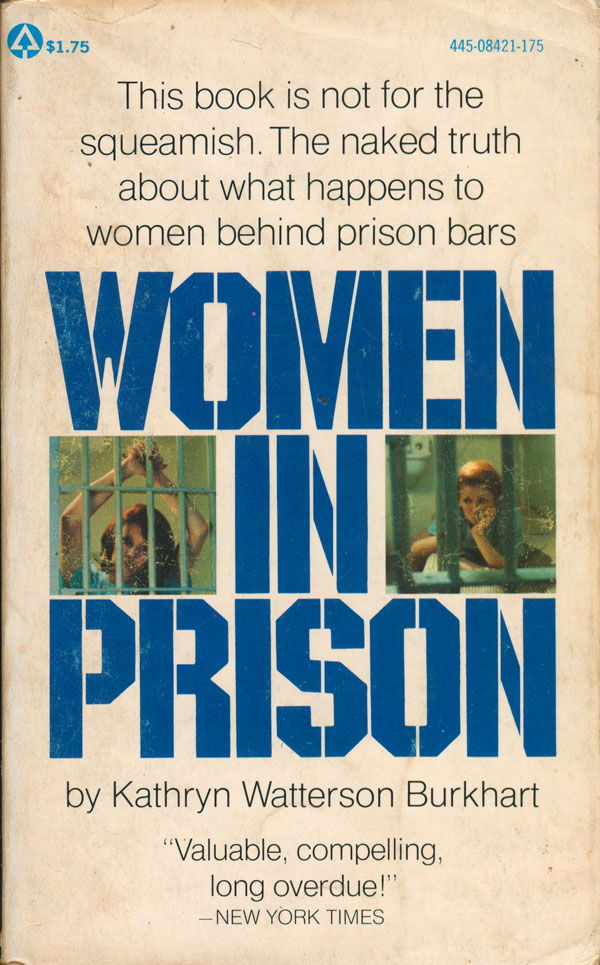

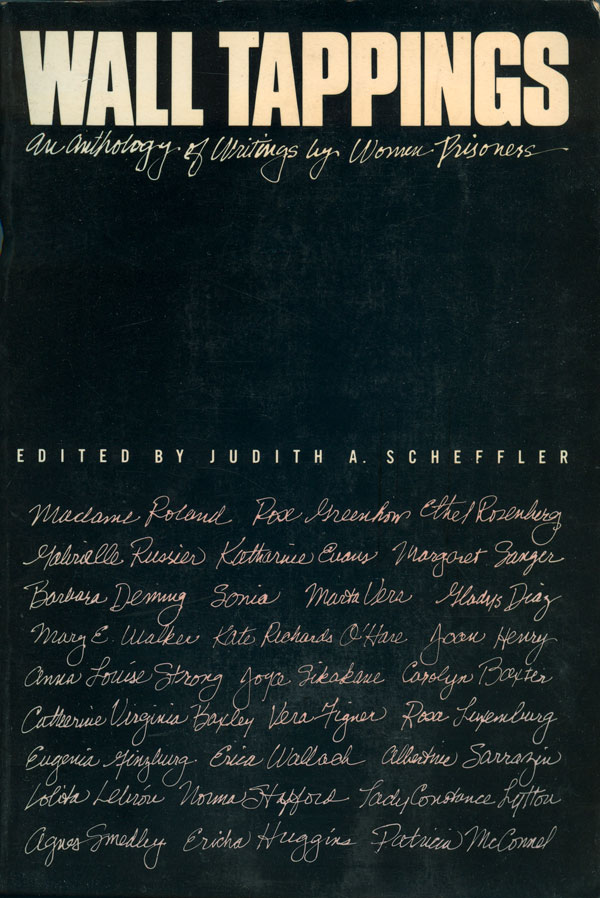

Talking about sensationalism, the Burkhart book cover below is about as out there as you can get, practically turning the measured discussion of the lives of women in prison contained within the book into an advertisement for a sexy story of depravity. Once again the bold stencil type, and then the sexualized inset pictures of the women behind bars, with the pull text promising “the naked truth!” The book to the right is amuch more subdued take on women in prison (and from 10 years later). The large black space in the center of the cover replaces the racy images, and leaves much more up to the imagination the horrors within prison.

Stay tuned next week for 11 more covers from this period of 1960-1986. I will be posting a bibliography for all these books together in 2 weeks.

interesting, josh… what do you think about the aestheticization of prison in porn, up to and including lil wayne’s song about fucking the police? does that represent the omnipresence of police in black life? every once in a while, i notice a story about a jail renting its facilities out to shoot videos… even if the use isn’t pornographic–let’s say, a comment on james baldwin’s “male prison”–do you think that’s problematic, especially when the subject is an activist, and the intent (conscious or otherwise) is to break him or her cool hand luke?

Not to sound too prude, but I don’t really have much experience watching prison porn, so I don’t feel too qualified to comment on it….

I’m actually not entirely sure what you are asking in your comment?

I’m simply trying to say that based on looking at many of these books today, particularly the U.S. mass-produced pocket paperbacks, they seem quite exploitational, trying to hype up the angry, dangerous, or (in the case of women) sexualized connotations of prisons in order to sell books.