Here’s the final installment of the Peter Kropotkin book cover series, 19 covers this week, 69 total over the five week series. Although what initially drew me to doing these post about Kropotkin was a focus on the all the different representations of his beards, he is actually an interesting subject for this kind of visual inquiry, as his writing has been published by hundreds of publishers in dozens of languages for more than 100 years. I’m sure these 69 books are merely the tip of the iceberg, and some additional research could really illuminate how Kropotkin was represented in different geographies in different time periods, and how those representations related to the design conventions of the day. But that is a project for a different day.

Today I’m going to go through the last of these covers, starting with another one of Kropotkin’s popular books, Memoirs of a Revolutionist. I like the 1962 Anchor pocketbook edition to the left for a couple different reasons. First, the simple sans serif text and the almost tourist-like photo of pre-Soviet Russian arabesque architecture are unassuming, it takes a minute to see that the building is actually completely dwarfing the people, and that it would take some serious revolutionary zeal to face off with the power of the Russian Czar and Church, a power literaly inscribed into the landscape. Second, the downplaying of the “Revolutionist” in the title is hard to imagine on a cover made today. This book would be published not by Doubleday or a any major publishing house, but a niche political publisher like AK or PM, who would likely feel the need to play up both Kropotkin as an important individual and his anarchist credentials in order to appeal to their audiences.

The two covers below were both published at least 10 years after the above, and both are build around Kropotkin as Revolutionary. The Cresset Library edition is from London, published in 1988, and has a classic box for the title and author, but it sits a bit awkwardly on top of the reproduction of a Soviet painting. I can’t place the painting right now (one I leave the comfort of posters, prints, and graphics my art history gets significantly fuzzier), but it is clearly of a black-caped, bomb-throwing anarchist, whose very presence is knocking saber-carrying czarist soldiers off their horses. To the right is the 1973 cover published by Zero Editions in Madrid. It is much more graphic, but the image is similar in some ways, a rifle-touring revolutionary climbing the steps of power. The hat and large overcoat are signature Russian, in case anyone was unclear of where this scene is taking place. Interestingly, the bearded figure looks a bit like Lenin. That and the red armband make this look like a scene from the October Revolution, something Kropotkin would surely not have wanted representing his work!

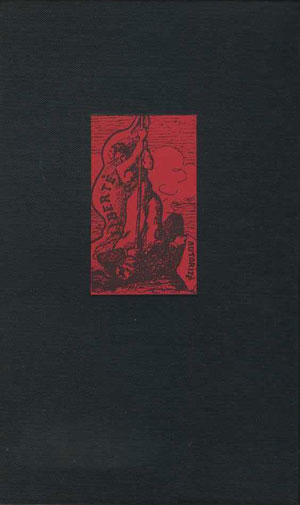

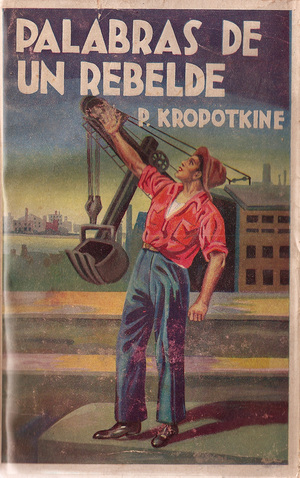

An etching of Lady Liberty stabbing authority graces the cover of the 1978 edition of Memoirs by London’s Folio Society. The small image is printed in black on red, and inset into a cloth bound hardcover, making a clean and handsome package. And next to that is a great cover I found at the Kate Sharpley Library. An old Mexican edition, the title is a modernist-style hand-drawn font, and the painting is somewhere between socialist realism and a hand-painted sign. Subtle it is not, with the workers arm being shadowed by the industrial power of a back-hoe. Maybe not exactly Kropotkin’s vision of revolution, but who knows, I don’t think He ever visited Mexico in the 1950s…

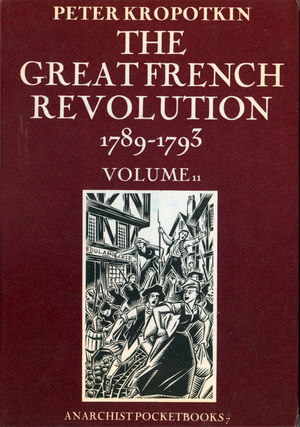

Kropotkin, like Marx (and many other 19th century/early 20th century political thinkers) did a lot of writing about the French Revolution and its meanings. Elephant Editions put out a nice 2 volume set in 1986, the covers designed by Clifford Harper with an inset image of one of his illustrations of the French Revolution from his book, Anarchy: A Graphic Guide (I failed to mention a couple weeks back that his illustration on the cover of the Elephant Editions printing of The Conquest of Bread is also based on an image from Graphic Guide).

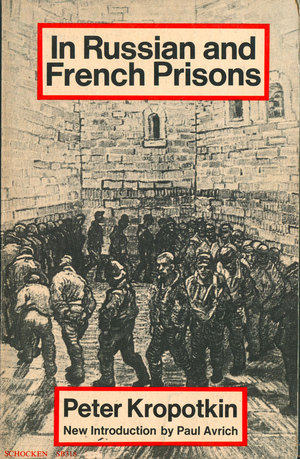

Kropotkin did a fair bit of time in prison (what self-respecting revolutionary hasn’t?), and he did some writing about it. To the left is the 1971 Schocken edition of In Russian and French Prisons, which has a cover designed by Barbara Kruger (yes, THE Barbara Kruger that went on to become an art super-star in the 1980s). It actually has all the same basic elements that she used in her future work: a black and white image, with bold sans serif type laid on top, highlighted by a red spot color border. I also just noticed that the image is a painting by Vincent Van Gogh, the very same painting used in color on the cover of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish I showed in Judging Books #41.

Next to that is a cover of a 1979 Russian edition of Kropotkin’s memoirs from his stay in Peter and Paul Fortress, published in Moscow by Detskaya Literatura. The Peter and Paul Fortress is the oldest building in St. Petersburg, and was used as a jail for political prisoners under the czars. This edition is illustrated, including the cover, by O. Korovin.

The State: Its Historic Role has gone through a number of editions produced by Freedom Press in London. To the left is the cover which is part of the series designed in 1987 by Rufus Seger, which I discussed at length last week. To the right is an earlier Freedom edition, I believe from the 1969. It is definitely from after they stopped using hand type-set covers (40s and 50s) but before the full shift to computers in the late 70s and 80s.

And here are two more editions of The State, both pretty uneventful. The German edition is one of series produced by Urast Verlag, all with the same basic cover in different colors, including the black box with title, the handwriting backdrop, and the odd inverse image of Kropotkin in the bottom right, looking like he is on fire. Not the most exciting cover to be found. On the right is a 1947 pamphlet edition by Haldeman-Julius, its most interesting attribute being that the covers (and insides) are letterpress printed and have a nice tactile feel.

I’m surprised I was only able to find this one cover for Kropotkin’s An Appeal to the Young, I know I’ve seen others but haven’t been able to track them down. This Freedom version is quite nice, with the Bodoni poster font like many of their 40s and 50s covers, but also a nice illustration of all of these ideas and activities swirling around the head of “the young.” I wish I had a copy of the actual pamphlet so I could trace the artist. Next to that is a 2003 edition of Ideals and Reality in Russian Literature by the publisher Diogenes in Zurich. The cover is very German, or Northern European, with a border, a clean serifed title and an enclosed illustration (which in this case looks a bit like a Felíx Vallotton graphic, but I don’t think it actually is).

Since Kropotkin’s work was almost all originally published between 1875 and 1925, it falls under public domain, so any publisher that chooses can put out an edition of one of Kropotkin’s works, without having to pay royalties. This is why there are some many of his books published by Dover Press, which focuses on keeping valuable public-domain works in print, and such a wide variety of other presses have published him, many publishing editions at the same time a half dozen other publishers have the same title in print. Until recently most publishers distinguished their versions by getting contemporary authors and thinkers (like Paul Avrich and Paul Goodman) to edit the books and write new introductions and contextual materials. It was always a fair amount of labor and capital to actually edit, typeset, and print a book, even if the content was “free,” so publishers didn’t do it lightly.

But now we have entered the age of Print-On-Demand, or POD. Large copy-machines or laser printers and basic binding equipment have been attached to computers to create machines that can publish anywhere from one to 1000 copies of a book at prices that are not significantly more expensive per unit than the price of printing books offset, where it is usually only with printing if you are doing a print run of 2000 or more. In addition, these machines are set up by third parties that are willing to print books by any number of publishers, who can sell a book through a website, then have the third-party print that single copy of the book and ship it directly to the customer. This costs the “publisher” almost nothing, the only overhead is their webpage, or the announcement for the book on Amazon or Ebay; they don’t need to keep inventory, so they don’t need a warehouse or a storefront, they don’t need any physical space at all. When you factor in the content being public domain, then their is almost no reason why hundreds of different entrepreneurial publishing companies can’t sell low-cost editions of any public domain title they can get their hands on, and that is exactly what is happening. Most of these publishing companies exist solely on someone’s desktop: they take low-quality reproductions of the insides of public domain books, slap pre-fab covers on them designed with stock graphics and the most basic of fonts, send the files to the printers, but the books up for sale on Amazon, and wait for people to buy them, at which point each book is digitally produced, one-by-one, and sent to the buyer.

Because of the above situation, their are literally hundreds of POD editions of Kropotkin floating around out there. The four below are my favorites. The two covers of Conquest of Bread are hilarious. Wet rocks stacked in front of a blurry sky? One of these chairs just doesn’t belong? Did someone just close their eyes and click on the stock photo their mouse just happened to land on? I’m not sure if the Mutual Aid covers are better or worse, but someone at least thought they were choosing images that fit the content. Old school library photo with the microscope is hideous, but noyt completely off. But the last one is by far the funniest. The yin yang symbol in the background sets the mood, lets us know this is about balance, and then the short, tall, skinny, fat, and hat-wearing people all holding hands and working together as the sun rises: the cover of a Kropotkin book if he was a contemporary life-coach. And as the final master stroke of genius, somewhere along the line he picked up the middle name Harry!