I got a great used book for my birthday, World Architecture 2 a large picture book of architectural trends from 1965. It contains many examples of Brutalism, an architectural style that was like a more extreme version of Bauhaus-influenced modernism (as a disclosure, I am not terribly familiar with architectural history or theory). In Brutalism the form of a structure followed its function, decorative embellishments were removed, and many of the engineering and functional elements of a building were laid absolutely bare. It was also known for its heavy usage of rebar/concrete as a stylistic and structural element.

My interest in this style of architecture is partly from growing up and being surrounded by it. My elementary school was an extremely modern building: low giant slabs of concrete, big windows, and a very modern playground with rounded grass knolls in the middle of a sea of concrete.

Over and over again, in the my years of public schooling, I found myself in these types of buildings. This style of architecture was endemic to civic projects from the 1960s and 70s, especially schools, but also in government buildings, stadiums, public housing, museums, and parks as well.

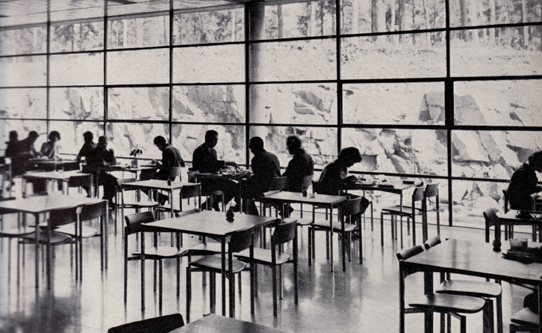

This brings me back to my birthday present, World Architecture 2, which is filled with photos of the good, the bad, and the weird. The photos are accompanied by essays from the architects that talk about their intentions and ideas. Often the architects and designers who worked on these projects had pretty radical and (even) proto-environmentalist notions.

I really enjoyed reading this critique of Spain’s problem with tourism and tourist development (once again, from 1965):

“Architects find themselves in the middle of the tourist machine. If he is honest with himself the architect has to solve problems before the politicians, sociologists, and economist enter the field. As has happened so often before, he now has to do their work in persuading the public against the whims of the monster tourist propaganda machine…. Even worse, the agents and speculator, the mechanics of the machine, bribe him in the form of quick fees for rapid results, so that the wretched hotel is open in time for the season.

The machine in Spain demands among other things that the whole variety of the peninsular is turned into a mixture of Ibiza and Andalusia, or modern parallel blocks based on a misguided notion of the Bauhaus and Athen’s Charter.

The architect protests, and advises, among other things: the use of local materials; that the building should use Mediterranean colors…, compact buildings against sun and dust, small windows against the strong light and hot sun, and quality for long-term profits.

The machine replies: We only build what we can sell, and we sell what the tourist buys.

The architect: Have you tried an alternative?

The machine: The risk!!

Perhaps capitalism can only risk subtopian holidays to subtopian tourists from subtopia.

Perhaps one day the tourist will learn to demand and expect an environment for his spiritual and physical refreshment. Perhaps politicians, technocrats, unions, and professional organizations will one day get together and solve the problem of leisure!”

(David Mackay, co-editor)

I like the idea that leisure is a problem to be solved!

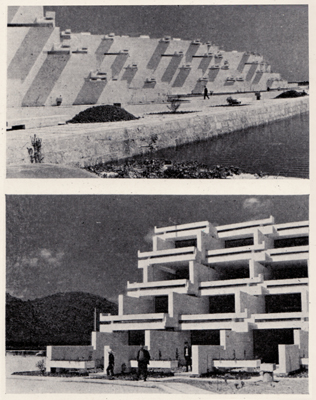

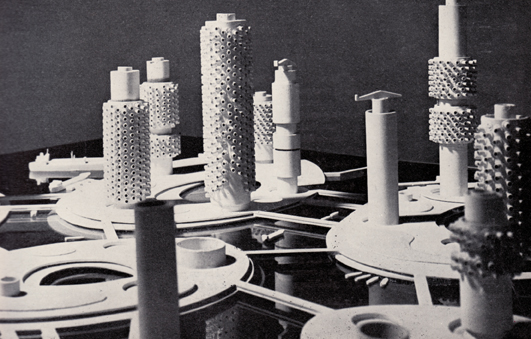

There follows some examples from Spain, one for a large scale tourist complex, which attempts to address the ‘leisure problem’ on the head by making an area for tourists that is contained and especially takes into account the idea of making public commons that are separated from automobile traffic and culture.

There’s also an uber modern building from Majorca that creates a dense living complex while giving privacy to its residents with its pyramidal type shape.

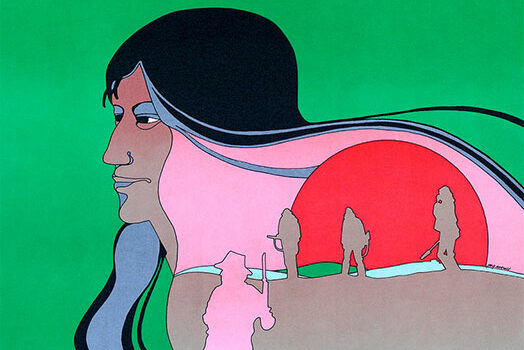

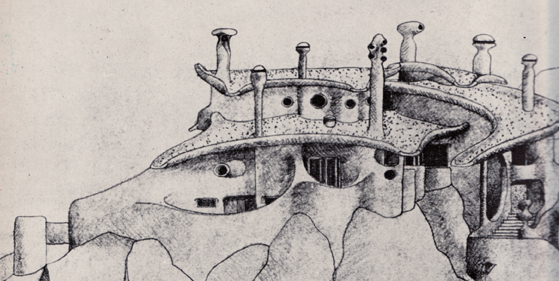

Here is a very 60s, very organic design for housing from Mozambique:

In many of these there’s similar ideas at play… how to deliver needed privacy for people’s living situations, how to also facilitate community through architecture and design, how to use natural elements (light and heat especially) and incorporate people into their environments. They’re decent ideas, and fascinating (to me) to look at, even though those of us who grew up in these places might question how effectively they accomplished their goals.

During the 1990s, as gentrification spread its way across America, developers tried to recreate the idea of Main Street. Pedestrian boulevards were added to strip malls, retro embellishments were added to new buildings, and largely forgotten (or red lined) neighborhoods were being touted for their ‘funkiness’. This was the dreaded new urbanism- with its accompaniment of historical amnesia and imperialist urban pioneers. These brutalist, gargantuan, concrete buildings with their exposed heating vent systems and external staircases started seeming less oppressive and a lot homelier, remnants of a time when there was hope in the future, when there were more ideas in architecture then how to make a Starbucks feel more real.

So I’ve grown to, if not like, then at least have a slightly more nuanced view of these places. I’m back at the same community college I attended when I was 18. It’s right on the edge of the suburbs, built into a hillside and surrounded by parking lots. But I enjoy all the openness in the campus, the multiple levels of public space, the built in squares and fountains between the buildings, and the way that the buildings use the natural hillside as a design element (but I loathe the absolutely horrid light in most of these buildings!). Also, I love sci-fi so I am attracted to these as artifacts from a non-existent future (and these places were often used as settings for lower budget science fiction films… off the top of my head: Fahrenheit 451, Alphaville, the later Planet of the Apes films, and let’s not forget Buck Rogers- the 80s TV show).

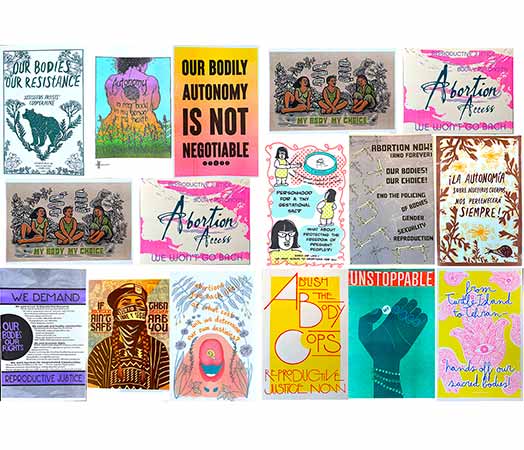

On the Justseeds blog I am hard pressed to think of any mention of radical intention in architecture. Yet what art-form (for those of us who live in cities anyway) has such a profound effect on how we live? I wouldn’t defend these buildings and complexes as assets to our lives, but I think they are intriguing to look at in the context of other political movements.