I wrote this essay a while back for Punk Planet which sadly is no longer being published as a print magazine. I wanted to put it up here because it relates to some other threads about artists appropriation.

Off with Their Heads By Dara Greenwald

Originally published in Punk Planet, #77

January/February 2007, p 94-98

Off with Their Heads By Dara Greenwald

Originally published in Punk Planet, #77

January/February 2007, p 94-98

In early 2002, a group of eight Chicago-based artists and activists gathered together to form a radical arts collective. They called the collective StreetRec and worked on creating memorable and resistant protest graphics to be disseminated widely for use in public space. Born out of the counter globalization movement and the critically engaged art community, they were interested in making art that would challenge the domination of corporate control and US hegemony. Part of their politics was an embodied critique of the over valuing of individual competition rather than group collaboration. This cultural tendency is particularly prevalent in the art world in which some of them participated. For this reason, they choose to credit all of the art they created to the collective and not to individual artists. They had no funding or sponsorship. They were simply a voluntary association of engaged artists with some graphic design skills and an offer from a sympathetic printer to help them out.

After several meetings and discussions, the group came to a collective decision to attend the protest against the World Economic Forum (WEF) being held in New York City that February in which they would bring their new creations. One member of StreetRec had seen a Vanity Fair photo spread (shot by the famous portrait photographer Annie Leibowitz) of the warmongers themselves: George W Bush, Dick Cheney, Paul Wolfowitz, and Donald Rumsfeld. They decided to modify and recontextualize these images and create larger than life cut out heads to be carried at the protest. A member of the group, recalls, “The Annie Liebowitz pictures of Bush and his cabinet were crying out for defacement. We discussed a variety of ways in which we could mutilate these images, from the grotesque to the culturally charged to the satirical . . . and we ended up with a smattering of all three.” Little did they know, that their visual interventions would travel far and wide and raise complex questions about artist appropriation, the free use of culture, and the commodification of dissent.

Since StreetRec was appropriating from a corporate magazine, critically and drastically changing the images for not-for profit dissemination, their use of these images might fall under Fair Use. Fair Use describes conditions under which copyrighted material may be used with out permission and there have been and continue to be long legal battles concerning the specifics of the laws. Regardless of the law, many people in the copyright liberation movement see the ownership of intellectual property for the generation of profits as damaging to the free exchange of ideas. Most copyright laws protect big corporations and other powerful entities. These laws can be stifling to creative development as well as political dissent. In a way, StreetRec and others like them can be seen as information Robin Hoods: taking from the rich (corporate content providers), and giving away to the poor (grassroots activism and free culture) for social benefits and sharing, not for profit.

The group created three heads approximately four-and-a-half feet high by three feet wide for the WEF protest. A member of StreetRec describes the heads this way: “One—Bush with ‘Enron’ sutures: arguably the most ghoulish of all the heads, Bush has a wide cut that splits his mouth well into his cheeks, and has a matching slice across his forehead. These wounds are closed by thick, ugly sutures, the ones on the forehead spelling out ‘Enron.’ Two—Cheney with the ‘Got Oil’ moustache: a sloppy oil moustache dribbling over the man’s lips, while on his forehead in looping liquid script are the words ‘Got Oil?’ satirizing a popular ad campaign for milk. Three—Rumsfield with ‘3000 Afghani Civilian Deaths’: Inspired by the infamous ‘Gods of Punk’ 12″ by Poison Idea, Rumsfield has the Afghani civilian death toll (at the time of making) carved into his flesh with uneven gashes. It’s important to note all of these signs were in lovely grayscale, with the only color being the various wounds and blood.” Each also had a teardrop tattoo; a jailhouse symbol indicating the wearer is a murderer. Graphically, these visual mashups were borrowing from and commenting on the media culture they were immersed in to create new meaning and dialogue.

When StreetRec arrived at the WEF protest in NY, one member recalls, “We were amazed at the initial reception of the heads when we walked to the starting point of the march. About 1000 people just started cheering wildly. It was really overwhelming. We knew at that point we had done something really provocative. We had no idea that they would travel like they did.” These same heads were also brought to a protest against the Trans Atlantic Business Dialogue, a Chicago anti-war protest, and to a Milwaukee protest with Illinois Peace Action.

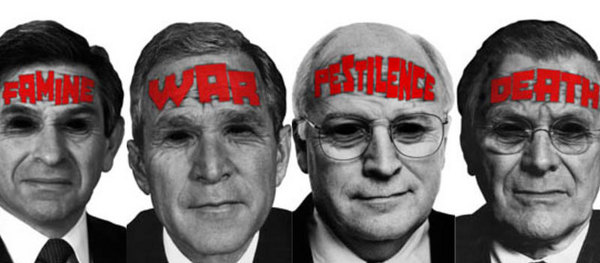

With the reception of the first set of heads, and in preparation for the January 18, 2003 national protest against the War in Iraq being held in DC, the group created a new series. This group of images was called “The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse”; this time the heads had the eyes blacked out and one word across their foreheads: Bush had “War”, Rumsfeld had “Death”, Cheney had “Pestilence”, and Wolfowitz was marked with “Famine”. They were also brought to several anti-war protests in Chicago including the International Day of Action against the War, February 15, 2003 (see image) as well as protests in other parts of the US.

At all the protests, the signs were documented by various media outlets and the resistant street spectacle entered the corporate media spectacle. Corporate media coverage is a much-debated arena in activist circles. Activists are at once seeking coverage from corporate media because of the huge audience potential and at the same time activists remain suspicious of corporate media’s tendency to misrepresent or debase subjects. Certainly StreetRec must have discussed these issues before hand, for the sheer size of the heads and their slickness in a protest context were sure to stand out and make for an excellent photo opportunity. In some circles, this is called Tactical Media, using creative tactics to create a spectacle that the media will pay attention to and thus enter your issues into a larger public dialogue. Regardless of this debate, however, these contemporary protest images spread around the world and Bush’s head with the word “War” were intricately linked.

Fellow protestors and the media loved these images more than the artists had ever anticipated. From Newsweek to the Revolutionary Worker to the South China Morning Post and The Times of India—protest photos that included the StreetRec heads proliferated around the globe. Ultimately, StreetRec felt their desire to infuse protest with newer, slicker graphics worked in communicating their visual and political ideas to the world. It was exciting that with so few resources, a small number of people could penetrate the media landscape on this large of a scale.

With the heads’ welcome reception and an intention to spread critical and free culture, the group decided to make the graphics more accessible to other protestors by putting up easily downloadable files on the web. They distributed flyers at the antiwar rally in DC that had a link to a site where anyone could download the heads. At the site visitors were greeted with this information and an email address: “Hello! Please feel free to use any of these images for your own activist/non-profit purposes. If they get any press, we’d love to hear/see about it. All images by the StreetRec collective 2002-03.” They also posted the link on activist website www.indymedia.org.

Later the group created a video called Retooling Dissent, which included a booklet with step-by-step instructions on how to make your own high-quality protest graphics. (See sidebar.) Soon, images of the heads (not just in photos from protests) started to appear in all kinds of places. Independent magazines such as Lumpen and AdBusters asked to reprint them. They were spotted on multiple websites, show flyers, and T-shirts. To use a marketing term, these images were sticky. StreetRec’s intention to distribute these images for free cultural use was working.

Then, one photographer made copyrighted postcards of a photo she had taken of the heads from the WEF protest, and it seemed that issues around copyright and attribution could get a little more complicated. Certainly, StreetRec had appropriated the original photos but had both re-imaged them and made them free for public use. Now it seemed, they were getting re-privatized. StreetRec began to see how difficult it can be to in assert and maintain free access to ideas in a culture driven by commodities.

In 2003, New York Times op-ed columnist, Paul Krugman came out with a book entitled The Great Unraveling published by WW Norton and Company. The US edition had a plain red and white cover and the subhead Losing Our Way in the New Century. The UK edition, however, had a collage of images including prominent placement of StreetRec’s Bush/Enron head and the Cheney/Got Oil? as well as a different subtitle: From Boom to Bust in Three Scandalous Years. Clearly, these different covers were a developed strategy on the part of the marketing department to sell books to different demographics.

StreetRec was surprised to find out about the book cover especially since it was so clearly a marketing move. The images on the cover of the book had not been re-done at all and were being used for profit however critical the book may have been. One member of StreetRec contacted the publishing company to discuss a possible honorarium or credit and asked for at least a few copies of the book for their files. If this book had been a not-for-profit venture, than it would have been another of the exciting re-printings of StreetRec’s work.

StreetRec weren’t the only people concerned with Krugman’s cover. Regardless of the books’ exclusion from the US market, right-wing journalist Donald Luskin at the National Review choose to highlight the cover images in his column as a way to discredit Krugman’s ideas. In a November 24, 2003 piece called “Running From Cover” at www.nationalreview.com, Luskin writes, “It took a simple picture for the New York Times to finally distance itself from America’s most dangerous liberal pundit…It’s a photomontage showing the face of President George W Bush with huge Frankenstein sutures across his mouth and brow, and the word ‘Enron’ stitched into his forehead. Vice President Dick Cheney’s face sports a Hitleresque mustache; the words “Got Oil?” are scrawled on his forehead. It is a hateful, shocking, and disturbing image.”

Even the Republican National Committee weighed in on this cover. Spokesperson Christine Iverson stated in the New York Times (“One Book, Two Very Different Covers,” Nov 23, 2003, Books p 2) that, “The fact that they are using a much different cover here in the United States is proof that his tactics are offensive to mainstream Americans.” The New York Times also attempted to distance themselves from it, spokeswoman Catherine J. Mathis stated, “ . . .we were never even shown the cover.” And finally Krugman himself, in the same Times story said, “It is a marketing thing, not a statement…I should have taken a look at that and said ‘What are you doing marketing me as if I’m Michael Moore?’”

Certainly if Krugman only was to benefit from the images as a marketing device, perhaps the company could have done some research about who to attribute the art to. But, protest art and underground culture is constantly appropriated wholesale by the market. If he planned to reprint the original photos by Annie Leibowitz, certainly he would have paid for rights, but grassroots art functioning in public space is easy for corporations to use without fear of repercussion. Regardless, the images had reached higher places of power and controversy than any of the artists could have imagined.

The heads brought out for the protests against the war three years earlier resurfaced in November 2005 in a review in the “Arts” section of, you guessed it, the New York Times. This time, they were not in a street protest, nor on the cover of a book, but appeared in perhaps an unlikely place, the Museum of Modern Art’s PS 1 in New York as part of an artist installation. The artist, Jon Kessler, had included the Bush “War,” Cheney “Pestilence,” and Wolfowitz “Famine” heads to cover an entire wall of his installation room. And although his installation was quite elaborate with multiple components including video, electronics, media photos, and sound, the image of the wall with the heads was what critics in both The New York Times and the Village Voice chose to include in their positive reviews. Members of StreetRec were receiving emails from friends asking if they had a show at PS 1 and/or wondering if they had been credited. None of the artists in StreetRec had had any contact with Jon Kessler.

Jon Kessler found the images in a book called The War in Iraq: A Photo History. The book is a pro-war book published in 2003 with an unfortunate introduction stating, “This new war of liberation lasted only 41-days.” Of the over 300 pages of photos, only three have images of protest against the war and it is there, on page 46, that the heads show up. Jason Turner, a photographer with AP Wide World Photos took the picture at the Washington, DC, January 18, 2003 Antiwar Rally that StreetRec had originally made the heads for. Kessler said, “I bought the image directly from the agency that represents the photographer who took the picture that I saw in the book. I was told that he, the photographer came to see the show…I cropped the photo and just used the posters.” He chose that image because, “There are other pictures of Bush in my show. That one had the power and energy that would have deserved the size that I was planning on blowing it up to.” Kessler paid Corbis for other images in the show. Kessler stated that he had no personal position on appropriation. If Kessler had paid a photojournalist who took a photo of a public art piece by a more well known artist such as Jeff Koons, would he have felt as at ease using the images? Perhaps there is something about the way protest art is valued by the gallery art world that excludes even asking this question.

One member of StreetRec responded to the Kessler installation in this way: “There was some exchange via e-mail (with members of StreetRec) about it for a few days but people actually seemed less inclined to do anything than any of the previous instances. This can be attributed to a real distance from the graphics and the group no longer being together. It can also be attributed to the fact that it was a pretty confusing situation as far as it being a critical art installation that was not apparently for profit (though I think we know that his work was actually for sale) . . . I thought it was more interesting and controversial that his work said more about the limits and responsibilities of appropriating radical aesthetics meant for street contexts for art-world contexts. Of course, there are also limits to appropriating Vanity Fair aesthetics for protest contexts, and they mainly are that you cannot really (legally) complain much when your shit gets jacked.”

People in StreetRec have had a mixture of feelings about the re-appropriation and re-use of their appropriated graphics. One member felt, “It was my impression that that project specifically was created for use without copyright or expectation for reward. If someone wanted to misuse a head with a bloody Enron stitched into the forehead, well then I’d like to see that.” Another member, on the other hand, felt, “I think it is always fine if someone takes them and reconfigures them, but to use them to sell your book or as your own unmodified ‘original’ art work, that’s bullshit and really damn lazy. Yeah, we took the photos from a famous photographer in the first place, but really modified them and changed them into something hideously new . . . “ And another felt that when free, open culture meant for the commons, is taken and copyrighted for the benefit of an individual or a corporation, it is unethical. S/He didn’t want credit or money, s/he just wanted the images to remain in the context of a free and open culture. The anarchist sentiment that property is theft extends to intellectual property as well. Not only does StreetRec not own the images the sentiment goes, nobody should.

As the heads continue to have relevance, they have continued to be used in ways that StreetRec intended: by protestors as a means of powerful, visual, public, political expression. Others have taken the images out of the commons and privatized them back into the world of copyright and ownership without changing the design in the least. Appropriation is both an important and inevitable part of a vibrant and living culture. The context and intention of use of appropriated culture raises difficult questions about renumeration for the labor of creativity, the nature and value of credit for work, and the means that one has to have a say in its use. In today’s world certainly corporations charge heavily for the use of their propriety material and grassroots culture continues to be robbed not merely of their labor and production, but of their intentions for how a free culture might function.

Special thanks to Josh MacPhee, Anne Elizabeth Moore, Blithe Riley, and Heather Rogers for engaging with me about this piece as well as the artists who contributed their thoughts.

SIDEBAR

Instructions from the StreetRec Retooling Dissent DIY Booklet

“Large scale signs for protest are often either hand-painted banners or professionally created by a print shop. Large-scale computer output could be seen as a middle ground between purely handmade and professionally done protest graphics. If you’re familiar with graphics software at all, make a striking sign that will last through several actions can be relatively easy.

The prices for large-scale output can vary widely, so ask around. Copy shops are going to be the main places with these big printers, but some art schools and universities will also have them. They usually take a low-res but large- size file for output. The advantages of computer design and output are:

• You can use photographic images and they will reproduce well in color or black and white.

• The lettering or typography is clear and easily readable.

• The images you create will be able to be reproduced across different media (video, print, web), at different sizes, as much as you want.

So get the file specs (i.e. what document size, what resolution, what file type) from whoever is going to print your file (hopefully for cheap), make a powerful image (defenselink.mil on the web is good for hi-res images of US heads of state and military hardware begging to be purposed), include type if you want, and print away.

Once your sign is printed, you need to mount it on some kind of backing. If it’s going to be a long action/march, you’ll want to mount it on something light so you can hold it up all day. The best but most expensive lightweight board is corrugated plastic, also called gatorboard. You can get this at an art supply store – the good thing about this stuff is if the cops start to get violent, it can double as a sturdy shield. However, gatorboard is almost prohibitively expensive, and the next best thing is thick foam core. Also available at art supply stores, foam core is lightweight but substantial, and has a good texture for mounting paper onto. If foam core is still too rich for your blood, I have also had some good results from mounting signs onto thick styrofoam insulation, which has a good strength to weight ratio and comes in huge uninterrupted sheets. It can be a little hard to work with, and you might need to test some various adhesives on it, to make sure they won’t melt it.

With this printout/backing board setup, I have experimented with a few different ways to mount the sign to a pole of some kind. The most successful that I’ve found is to put nylon cord through the backing board and then glue the print on top of it. You drill holes in the board, then poke the cord through with a screwdriver. Remember to cut the cord longer then you think you’ll need, you can always trim it later. With these ties, you will be able tie the sign to a pole of any kind (some cities will only let you take in cardboard tubes rather than pvc pipe or wood). See diagram below:

(Diagram here)

To glue your print to the board, I find the best glue is a heavy-duty spray adhesive. Spray 77 is a good one, but there are plenty. You’ll get a much better price on adhesives at a hardware store than at an art store. Spray down your mounting board with the adhesive, getting a good coat especially at the edges. Once your board has a good coat of adhesive on it, slowly lay your print onto it while someone else smoothes it out, being careful the press out bubbles; this usually takes 2 or 3 people to do effectively – two lowering while one smoothes.

After you have your ties through the board and the print glued on, for added durability/waterproofing, you should coat the print in spray acrylic clear coat. There are a wide variety of clear acrylics available at the hardware and art store, with the cheaper ones being available at the hardware store. This way if your print gets rained on, the dyes won’t run.

Though this process sounds elaborate, once you have the materials you can mount a sign like this in an hour. Good luck and keep up the fight!

StreetRec

These heads and other examples of the defacement of powerful people have been used in protest throughout the US, and we have set up a website with multiple download options for the further dissemination of such graphics initiatives. www.appliedsemiotics.com/heads.

As we have presented workshops and screened this video, it has become increasingly clear that we need to produce diagrams for the StreetRec projects. Although the StreetRec projects are some of the simplest to produce there are many technical issued which could be encountered in the design and material decisions when attempting to appropriate these technologies. Feel free to contact us about any great successes or failures with these projects.

Street.rec@counterproductiveindustries.com

Like the other article for Shepard Fairey, the reality is that its almost impossible to defend this kind of artwork without either trying to shame people (who just laugh at you while they go to the bank) or suing them in courts (which feels dirty in and of itself).

That said, I don’t think the radical community has come up with a sustainable way for it to support its artists. We wonder why individuals burn out with their art, and its mostly because there doesn’t seem to be a mechanism in place to financially support them without encouraging the same kind of capitalist relations (buying art, t-shirts, etc). Its a tough row to hoe.

As inspiring post with creative advice, an antidote for revealing real evil. Thank you. Warren Schaich

Really inspiring photo blogspace! If only more could have been done to the warmongers themselves (a hearing on the validity of the war perhaps) rather than just defacing the portrait photos. Shame on Liebowitz for taking those photographs in the first place.

Great photo! Pity the magazine went under, probably due to lack of interest. This is such a pity because if there was any justice those criminals pictured would be brought to stand trial for their crimes.

This is such a helpful guide.