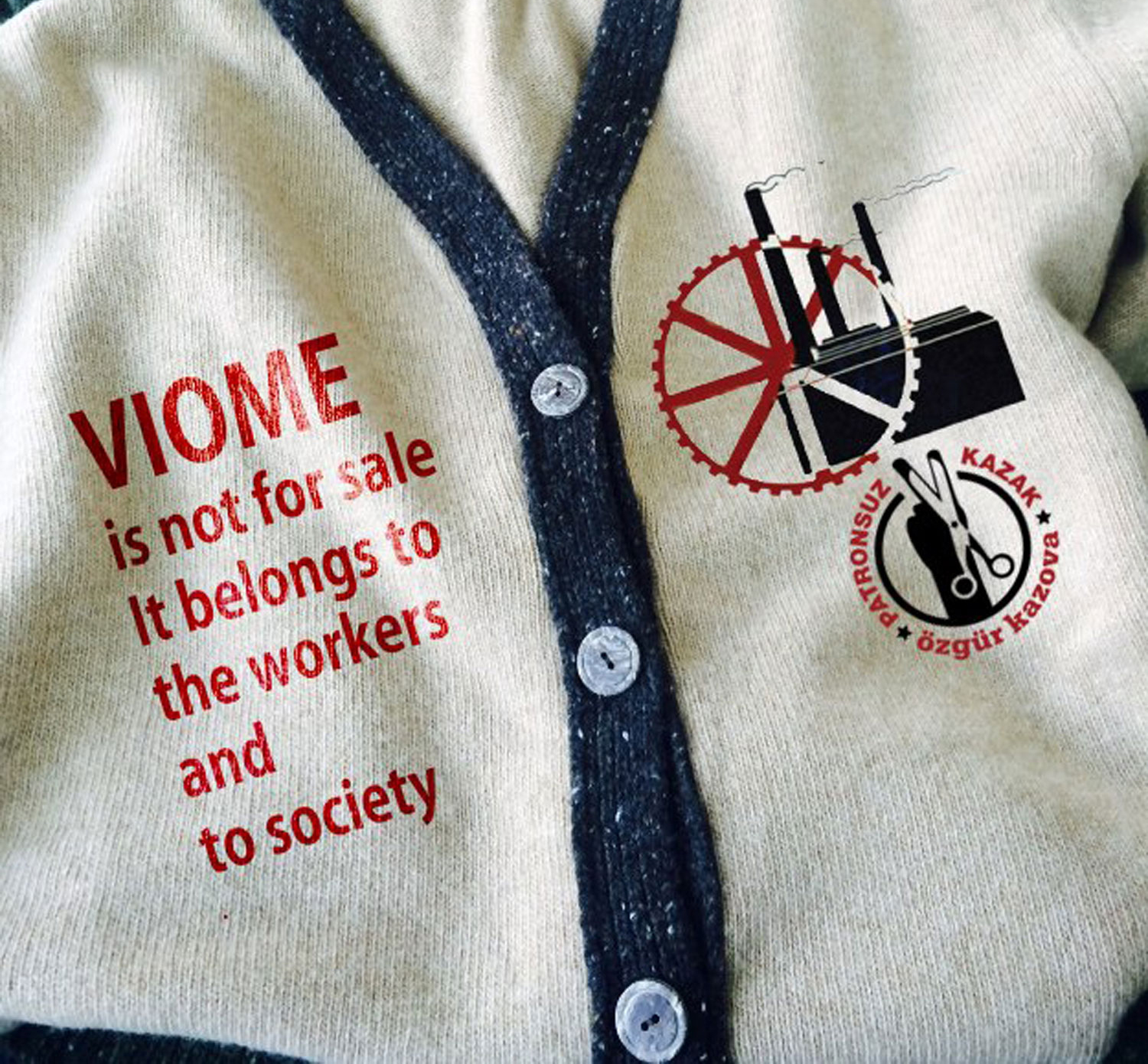

While on a trip to Istanbul last December, I spoke with Ezgi Bakcay, a curator and member of Karşı Sanat, a local artist run space and cooperative. She told me about an amazing worker owned cooperative called Jumpers Without Masters or Ozgur Kazova (Free Kazova) Textile Cooperative. The cooperative emerged in conjunction with the 2013 uprising at the Taksim Gezi Park, and has become an important symbol of the movement and a reminder that the struggle continues despite growing political repression in Turkey.

On February 27, 2013, workers began occupying their clothing factory in the Eyüp district of Istanbul. The occupation evolved into a worker run textile cooperative and on November 17, 2014 workers began producing Jumpers Without Masters not only to secure an income but to join other international freedom, labor, and economic justice movements. The cooperative believes in the principles of International Cooperative Alliance:

- Democratic self-management between members.

- A structure based on open membership and voluntarism.

- An economic model based on equal share.

- Independent production based on self-management.

- Permanent education, training and knowledge sharing.

- Cooperation between cooperatives.

- Solidarity with all social struggles.

Learning about this occupation and the resulting worker owned cooperative reminded me of the 2008 and 2012 Republic Window and Door sitdown strike and occupation in Chicago that lead to the formation of a worker owned cooperative called New Era Windows. Many local Chicago activists and artists including myself supported the strike and occupation.

In hopes of connecting the dots and promoting international solidarity and the struggle of the Özgür Kazova workers I recently reached out to Ezgi to learn more about the cooperative, the local artists working with it, and her thoughts on the importance of artists creating and supporting cooperatives.

Aaron Hughes (AH): Why did the Kazova workers first occupy their factory?

Ezgi Bakcay (EB): The story of Özgür Kazova starts in the last week of January 2013. At that time the workers of the Kazova textile factory were put on a one-week leave by their bosses, without having received their salaries, let alone overtime pay, for several months. The bosses told them that upon returning to the factory one week later they would receive their back pay, but instead they were met by the company lawyer who informed them that all the ninety-five workers had been fired because of their absence for three consecutive days. Meanwhile, the bosses had disappeared, taking with them anything of value and sabotaging the machines they couldn’t bring with them. The bosses left the workers without their salaries and without their means of production. The workers found themselves without jobs, income, and any legal rights.

The Kazova worker resistance began as a weekly protest march from the neighborhood’s central square to the factory, but as soon as they learned that, in their absence, the factory’s former managers were robbing the factory of anything of value, the workers decided to occupy their former workplace.

AH: What did the occupation have to do with the Taksim Gezi 2013 uprising?

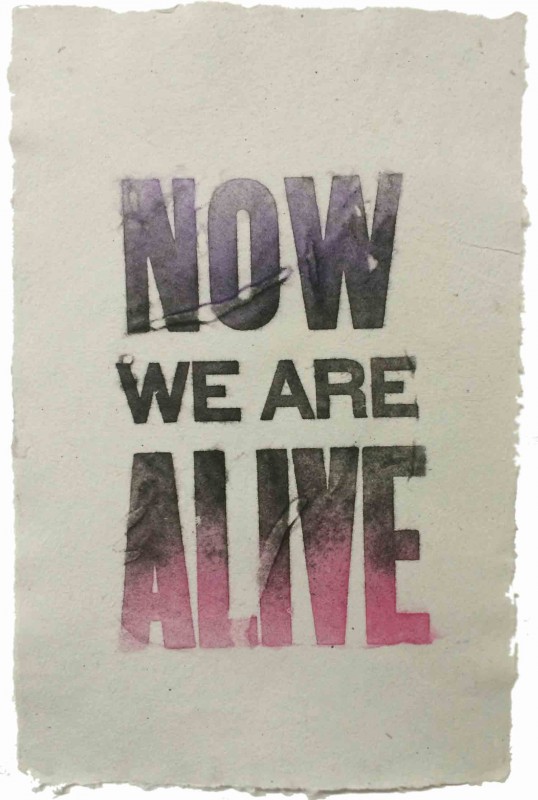

EB: The day of Gezi uprising was also the first days of the Kazova resistance. And by chance the workplace was near the park. During Gezi people from every sector, every layer of the society, who normally would not stand together resisted shoulder to shoulder. But Gezi wasn’t just a protest; it was an experiment in reclaiming space, time, bodies, and identities. It was an experiment and experience of radical self-management in the centre of the city.

Özgür Kazova was born thanks to this creative and productive socio-political event and then the factory occupation give birth to the idea of self-management in this liberating atmosphere by the support of the people from every sector and layer of the society.

AH: Why did the workers decide to form a cooperative and why did they choose to call it Jumpers Without Masters?

EB: Their rage was very personal. However, during Gezi days and with the effect of the right encounters with different political positions, their personal goals evolved into political ones. Their struggle wasn’t just about receiving a salary, but an honorable struggle for a new life.

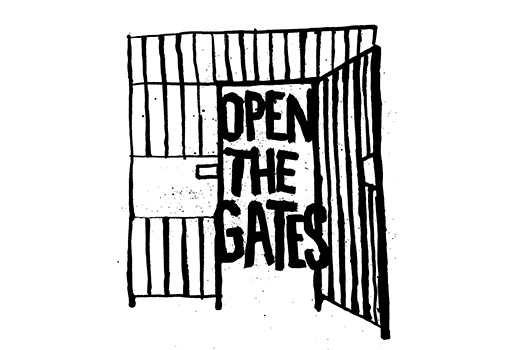

The workers knew that their occupation would end one day, but before it did that they would not give up the freedom that they earned through their occupation, their freedom from being in the service to any boss. Their struggle became a resistance against all bosses, against all masters, and against the dehumanizing condition of living in a capitalist system. Through the course of the occupation and with their free time they discovered their desires, talents, self-sufficiency, and self confidence. The cooperative was a tool for building such a sustainable economic life and Jumpers Without Masters was the name of the products of this way of life.

AH: What role have artists played in supporting and collaborating with the Jumpers Without Masters cooperative?

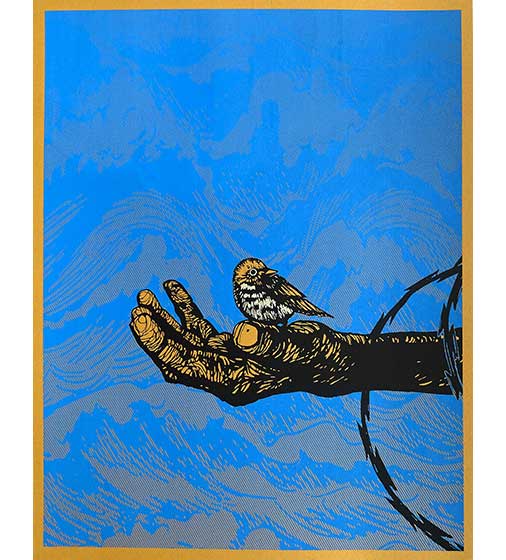

EB: Since the occupation began a group of artists have been with the workers helping with production and promotion. But more important than these acts of solidarity the artists and workers became friends.

For the artists it was an encounter with the idea of the unalienated work with free time and a new idea of creation. The history of working class struggles is full of this kind of encounter. Jacques Rancière’s work, La Nuit Des Proletaires [or The Nights of Labor in english] has overturned some of our most cherished cliches about nineteenth-century working-class politics. Nineteenth-century workers sought out proletarian intellectuals, poets, and artists who were able to articulate their longings. At night, these worker-intellectuals gathered to write journals, poems, music, letters, and to discuss issues. The worker diatribes they composed served the purpose of escape from their daily worker lives. In the case of Jumpers Without Masters cooperative also the leftist political organizations want to define their existences always in the frame of working class identity. But the workers don’t want to survive like a worker. Their struggle was for free time, for the liberation of their bodies as humans, not as workers. So dialectically, when the workers are “without master” they are no longer “workers” but simply human. As Marx says elsewhere, “if the silkworm were to spin in order to continue its existence as a caterpillar, it would be a complete wage-worker.” The surplus value of their labor will be their free time. Thanks to this free time and free conditions of production the they have been able to takeover and appropriated creative practices to tell their story and further their cause. Now they have friends among the artists, writers, academics, journalists. They are in the cultural space with their products, ideas, and experiences. They supported the artists in building an artist run cooperative at Karşı Sanat, in İstanbul.

AH: Have there been times that artists’ support has hindered the occupation and cooperative?

EB: We can speak about this as a larger question of the aestheticization of politics. Sometimes artists’ engagement with a struggle can be more symbolic than the situation demands, especially when the artists are helping with promotion of the struggle. There is perhaps an unintentional slippage into promoting the resistance as a kind of cliched idealized heroic workers struggle, but workers are not heroes. They are people trying to survive, win their freedom, and work through all the ugly contradictions of humanity. Furthermore, in these kinds of intense situations people’s lives are changing dramatically making it hard to represent their transforming resistance.

Additionally, at times when artists would come to the occupation with short term projects they would unintentionally make unrealistic commitments and foster unrealistic dreams. When their projects were over, the workers would feel like they were used or dismissed. These problematic interactions would damage the organic relationships within the group and cause emotional instabilities that were very dangerous to fragile collective experiences. Artists need to be aware of, and share in the responsibilities and consequences of their interventions into the Kazova workers’ lives and others’ lives.

AH: What is your hope for the future of this movement and how might artists best be engaged in this movement?

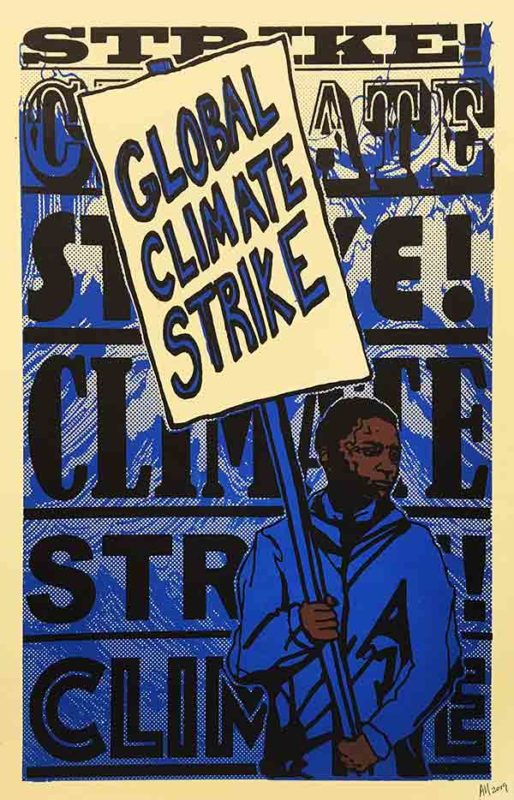

EB: Artists can join this movement by producing graphics for the t-shirt, jumpers, and textile designs of Özgür Kazova. Artists can also share the story of Özgür Kazova, organize solidarity events, and/or find some new locations for Özgür Kazova products. But the most important solidarity act would be, to be aware of the struggle for economic justice within artistic and cultural production. Artists should declare that they are also a part of this struggle, both in their lives and production processes.

Artists can position themselves in solidarity with other social movements by first recognizing their relationship to the capitalist system, big institutions, decisive actors, and with the “masters”/”bosses” of the cultural industry. Today, art functions like a religion. Art and culture mystify the concrete reactions between social actors and systems of power. Art and culture function as symbolic capital for those in power. And this symbolical capital pretends to justify the perpetuation of the exploitation and precarity dominating the art world, but it does not. This acknowledgement can be a the first step toward politicization of the art scene.

Artist run cooperatives are one of the most important tools in this struggle to create an alternative sustainable political-economic model of production. Hence, the creation of an artist cooperative should be seen as one of the greatest creative and aesthetic acts an artist can realize. A cooperative is the antithesis of the neo-liberal consensus and the process creating a cooperative is the process of reclaiming the sensibility between humans, nature, and a society alienated by a dehumanizing economical system.

Art cannot be political by producing discourses, images, and symbols of politics. Art can only be political by enacting politics.

Ezgi Bakcay is a member and curator with Karşı Sanat, an Istanbul based artist run space and cooperative. Support Jumpers Without Masters or Özgür Kazova (Free Kazova) Textile Cooperative by purchasing their clothing online:

Website: http://ozgurkazova.org/tr/

Etsy: https://www.etsy.com/shop/FreeKazova?ref=l2-shopheader-name

Ebay: http://dukkanlar.gittigidiyor.com/Ozgur_Kazova

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/OzgurKazova/info/?tab=overview

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OlnUz2Zi9bQ

Read more about the Jumpers Without Masters or Özgür Kazova (Free Kazova) Textile Cooperative; From Istanbul to Thessaloniki Occupation, Self-Management, Production Kazova: Weaving Freedom Loop By Loop.

All images are from Jumpers Without Masters or Özgür Kazova (Free Kazova) Textile Cooperative Facebook Page.