In her recent book Sociología de la imagen, Aymara sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui writes that ‘la descolonización solo puede realizarse en la práctica.’ Rivera Cusicanqui maintains that the only way to enact and realize a decolonized existence is by living and practicing decolonized ways of being in the world. I hope that many of those reading these reflexiones, without needing to be convinced, agree with this propuesta. In fact, I believe that this is exactly what many of us our searching for – a way to be in the world that is neither fully prescribed nor circumscribed by either the market or the nation-state. And it is precisely from Indigenous societies and ontologies and epistemologies, not surprisingly, that non-Indigenous peoples can learn important ways of practicing descolonización.

Throughout her scholarly and community-based work, Rivera Cusicanqui facilitates the locating of a space where we can think and act in ways that are neither fully contained by capitalism, colonialism, nor heteropatriarchy. Even if we cannot wish away these structural oppressions, we can still imagine and enact a world a beyond/before them. As a theorist and activist, Rivera Cusicanqui – and many Indigenous feminists in the global south – is simultaneously writing some of the most interesting and important anti-colonial theory today, as well as living at the heart2 of the movement to imagine new/old worlds. Unfortunately, many of the Spanish-language texts written by Indigenous feminists like Rivera Cusicanqui, Julieta Paredes, and Adriana Guzman, to name only three important voices, remain untranslated into English. So, how do monolingual Anglophone readers gain access to these important views?

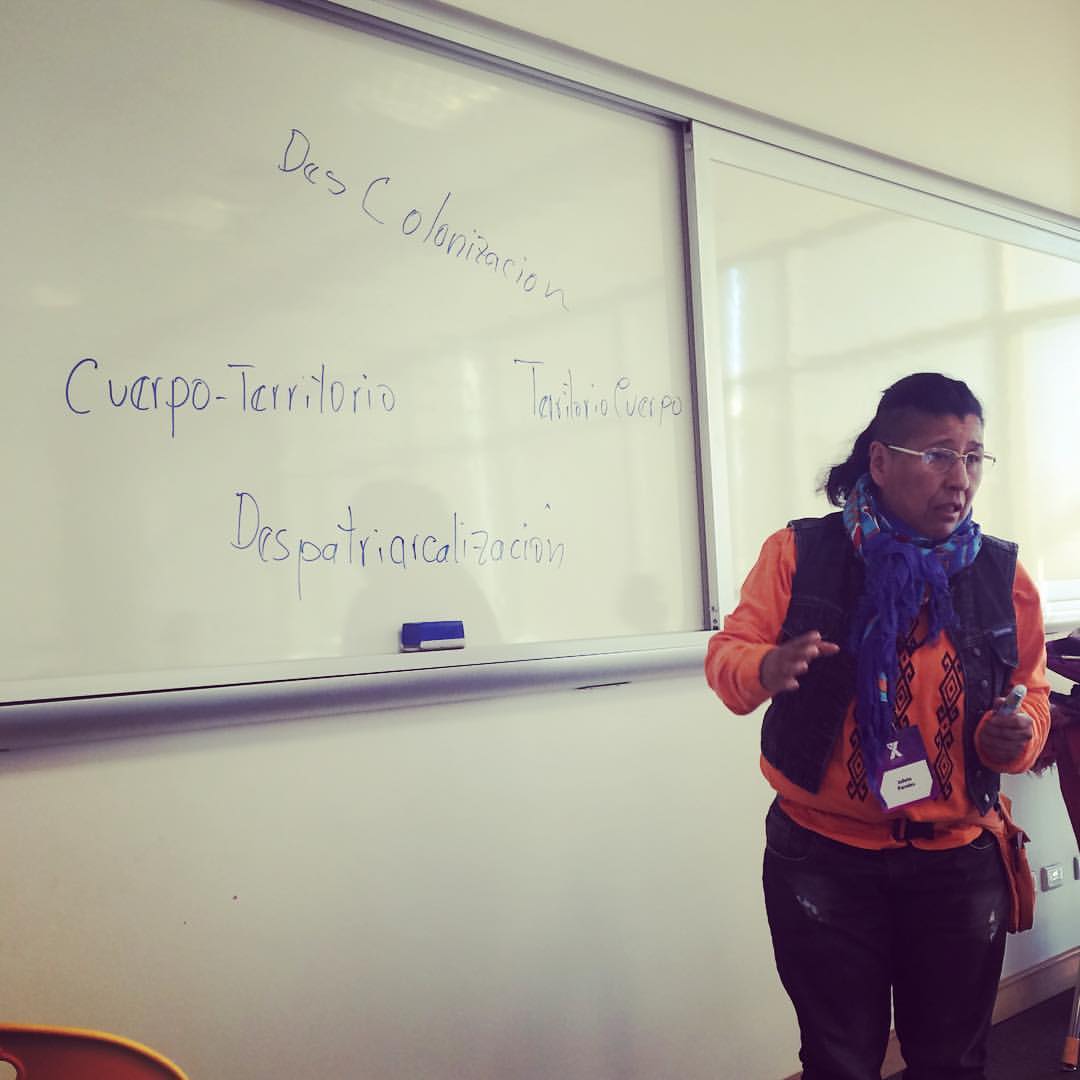

During a recent Working Group in Santiago, Chile – titled Territorio-Cuerpo y Cuerpo-Territorio: Comunitarian Feminism and Indigenous Sovereignty – participants collectively worked through the four-point constellation that makes up the cruz del sur of the central ideas of feminismo comunitario. As Julieta Paredes so intimately discussed during the group, we worked with the following cardinal points:

– cuerpo-territorio;

– territorio-cuerpo;

– descolonización, and;

– despatriarcalización.

For more on the brilliant and transformative work of feminismo comunitario, watch a few episodes of Despatriarcalización Ya!, a Bolivian television program hosted by Julieta and Adriana, or read one of their books. For shorter texts, I’ve written brief encyclopedia entries on both Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui and Mujeres Creando, a previous anarco-feminist collective that Julieta helped found in Bolivia.

During our time working together in Chile, we spent significant time translating back and fourth between Spanish and English – languages that already struggle to understand and describe those Indigenous ways of being that are outside both patriarcado and colonialización. In our Working Group, we had participants from across the continent who were Indigenous, settler, and arrivant, as well as those who straddled multiple categories. Julieta drew beautiful constellations and diagrams, of the cruz del sur, as well as of the cuerpo-territorio and territorio-cuerpo. Although we met only for a single week, we actively practiced descolonización – something I struggle(d) to do, both before, during, and after the Working Group.

During the group, Adriana Guzman – a feminista comunitaria from Bolivia – offered a propuesta for those of us working in English: to not translate the main conceptual ideas of feminismo comunitario into English. Instead, we should keep these terms in their original Spanish. For her, and many in the Working Group agreed – myself included – we frequently reduce descolonización from an active process (verb) into an object of study, decoloniality (noun). Although part of this has to do with translation, another aspect has to do with the centrality of certain ideas in English-language discussions of decolonization. Once this linguistic transformation happens – and descolonización becomes decoloniality – the object (decoloniality) becomes both knowable and obtainable. As others have been asking, from where did this dominant discourse on decoloniality come? Who are its main thinkers and actors and why them?

As an example, I only have to think about the Michif language, one of the primary languages of the Métis Nation. In Michif, a post-contact Indigenous language, nearly all nouns and noun structure are drawn from French, while verbs and verb structure come from Cree. Unlike creoles and pidgins, Michif is a mixed-language that illuminates the fundamental ontological differences between Western societies and Indigenous ones: actions versus objects. Adriana’s propuesta – to not transform (or translate) descolonización and despatriarcalización – maps well onto my own constellation of Indigenous and anticolonial ways of being in the world.

But, postcoloniality and decoloniality need to be Indigenized from an inherently feminist perspective. Perhaps, this responds to part of the dilemma we are facing at this moment. During graduate school, I studied postcolonial and decolonial theory and artistic practices throughout the Américas. A decade later, however, I am still waiting to see methodological and theoretical frameworks that adequately serve those of us hoping to understand the interrelationality and intersectionality – we may need to think about ways to make sure we do not objectify and thingify these processes – of art, culture, politics, and sovereignties across Turtle Island.

What emerged during my time in Chile, and this has been rising among Indigenous activists, intellectuals, and artists for a few years now, is the potential incompatibility of elements of the decolonial option with those of Indigenous sovereignties and their relationship to the cuerpo-territorio and the territorio-cuerpo. Many of my peers, and I would include myself in this collectivity, are disappointed by the ways that Bhabha’s postcoloniality and Mignolo’s decoloniality diverge from the overtly anticolonial and anti-heteropatriarchal framework of that offered by feminismo comunitario, Both postcoloniality and decoloniality – those prefixed (meaning those terms with prefixes, as well as those concepts that have become fixed) forms of coloniality – are neither inherently anticolonial nor noncolonial.

What many Indigenous feminists are doing is articulate – in their respective languages and epistemologies, as well as in European languages – ways of being in the world that are not fully contained by the ‘coloniality of power’, as Anibal Quijano would have it. The active process of contesting colonialism or, as it seems more appropriate these days, actively living in non-colonial ways, as Rivera Cusicanqui reminds us, can only be realized through practice.

All too frequently, decoloniality – the ‘thingification’ of active resistance and survivance – transforms active anticolonial resistance, as well as those alternatives that exist outside this violent system, into a knowable (and ownable) thing. In the same way that descolonización and despatriarcalización are untranslatable, so too are Indigenous ways of being non-objectifiable. In a manner that resists being transformed into capitalist labor-time, Indigenous and non-colonial actions can never become ‘things’ and, therefore, can never become commodities of either the market or the nation-state. By practicing descolonización, we are, in fact, living the world we want to have.

NOTES

1. I offer the preceding reflections with the caveat that they were written a few days after returning home from time spent co-convening a working group in Chile with Julieta Paredes, Skawennati, Rodrigo Hernández Gómez, and Dot Tuer. My reflections are quickly developed thoughts that I offer publicly as a way to commence conversation in an equitable and open way. As part of my living body of ideas, these thoughts are neither fixed nor permanent. I just needed to share them at this moment. As such, also forgive me for any typographical or grammatical errors.

2. Tzeltal theorist Juan López Intzin is doing interesting work on Mayan conceptions of the heart.

CHANGE: Mapuche territory is known as Wallmapu. Although, I initially used the term ‘territorio Mapuche’ in the above subtitle, there was some concern over my employing a non-Mapudungun term to describe ‘Mapuche territory’ or more appropriately ‘Mapuche territories’. I fully understand and agree with this critique of my use of language. When initially writing this reflection, I employed the term ‘territorio Mapuche’ to think about the ways that Wallmapu – and other Indigenous territories across Turtle Island and Abya Yala – link up with the ideas put forward by feminismo comunitario. I used the term ‘territorio Mapuche’ to connect it with ‘territorio-cuerpo’ and ‘cuerpo-territorio’. I wasn’t using the ‘territorio Mapuche’ as a place name, but rather as a way to think about Indigenous territories in relationship to the ideas of territorio-cuerpo and cuerpo-territorio. I don’t think this was directly communicated in the reflection very well, if at all. As such, I have have re-named the article to include the term Wallmapu.