Above: Native-American activists Amy Anderson and Mari Villaluna, with Chinese-American elder Pam Tau Lee

One of the leaders working to take down the New Deal-era murals at George Washington High School in San Francisco (unceded Ohlone Territory) is a friend, a Native American/Filipinx comrade, with whom I’ve collaborated on art projects, and whose child I’ve watched. I stand by them and the Indigenous and African American activists who are calling for the removal of the murals.

I have to admit, it wasn’t an easy decision. On an intellectual level, and as an artist myself, I understand the perspective of David Bacon and other Left writers on Arnautoff’s intent and progressive politics. Many folks whose work and writings I’ve admired and respected have expressed their opposition to the removal of the murals, people like Lincoln Cushing, Art Hazelwood, Doug Minkler, Jos Sances, Carol Wells, and my friends Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Chris Carlsson.

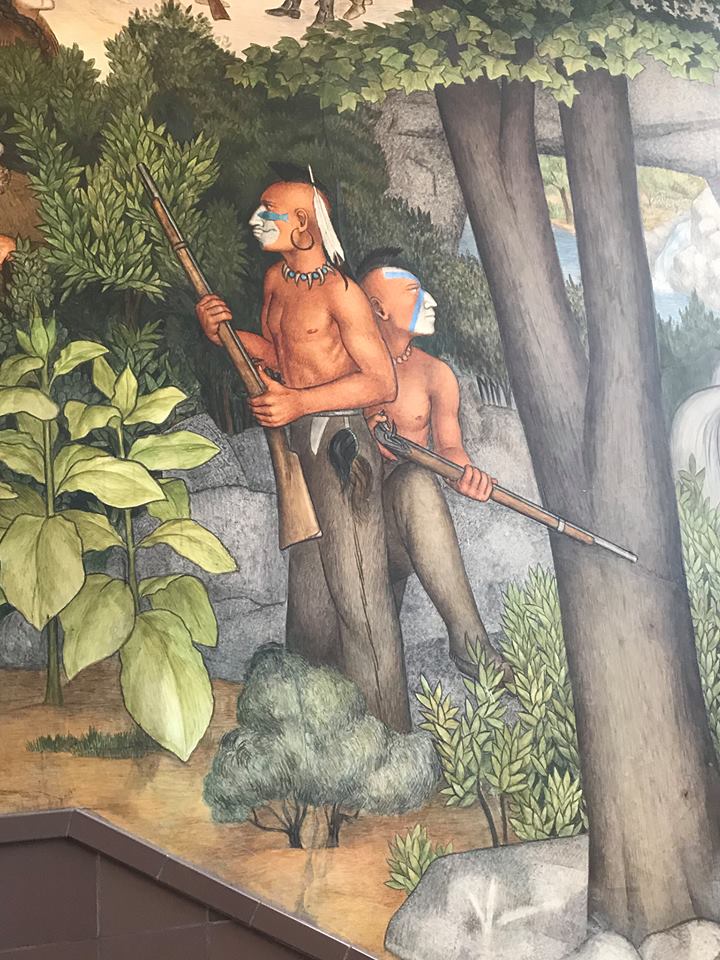

Victor Arnautoff, as a Communist New Deal-era master muralist, painted the reality of George Washington as he saw it: including Washington as a slave-owner and Indian killer. If anything, the images in Arnautoff’s mural, with Washington pointing to Westward expansion and settlers in gray walking over the dead body of a Native American, are mild in comparison to George Washington’s actual role in Indigenous genocide:

In 1779 Washington “instructed Major General John Sullivan to attack Iroquois people. He said, “lay waste all the settlements around… that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed.” In the course of the carnage and annihilation of Indian people, Washington also instructed his general not to “listen to any overture of peace before the total ruin of their settlements is effected.” His anti-Indian sentiments were again made clear in 1783 when he compared Indians with wolves, saying “Both being beast of prey, tho’ they differ in shape.” After a defeat, Washington’s troops would skin the bodies of Iroquois from the hips down to make boot tops or leggings. Those who survived called the first president, “Town Destroyer.” Within a five-year period, 28 of 30 Seneca towns had been destroyed. (from Indian Country Today)

The murals were cutting-edge and radical for the 1930s when they were painted, and it’s still surprising that Arnautoff got away with his critical portrayal of “the Founding Father,” while other San Francisco New Deal murals faced censorship and Right-wing attacks.

Having observed recent censorship here in San Francisco, for example against murals by young people of color depicting the Palestinian liberation struggle, the demand to paint over the murals gives me pause. But unlike the Washington mural controversy, these prior attempts at silencing the reality that young people paint didn’t rate the national attention that this has generated. To compare a demand to remove demeaning images in a high school is a far cry from the kinds of cultural destruction by powerful forces, whether by McCarthyism or the Taliban, to which some on the Left have compared the demands. These arguments are oddly similar to the arguments made by the racist Right against the removal of Confederate flags and statues.

While it is a mostly white crowd that has voiced the loudest opposition to the removal of the murals, it’s also a generational question, cutting across race and ethnicity. For Leftists my age and older, the New Deal of the 1930s still holds a special significance: a time when the CPUSA was able to organize strong multiracial coalitions, and when the Depression and people’s organizing brought at least a part of the Federal government to the side of the people. The New Deal murals are among the legacy of this moment that many of us hold dear, and also represent something our elders fought to preserve in the face of censorship, McCarthyism and later the new Right-wing forces that have tried to erase those wins.

But it is incumbent on us to acknowledge the consequences of privileging how we uplift this art and history OVER the impact that the images may have on young people who experience it every day – how this prism blinds us to art’s impact on others, to humility and compassion. As activists for social justice, we need to constantly reassess our positions, and understand how these positions support or hinder centering the demands of those most impacted, how those positions support or hinder building solidarity and the kinds of multiracial formations necessary to build real people’s power.

This should be the real legacy of the New Deal that we should be focusing on.

THE INVISIBLE AGENCY OF THE OPPRESSED

Despite exposing one “truth” about George Washington, the murals reflect a white-dominated narrative of the U.S., with little space for the agency of Indigenous, Black and Brown people claiming their own liberation in the face of oppression.

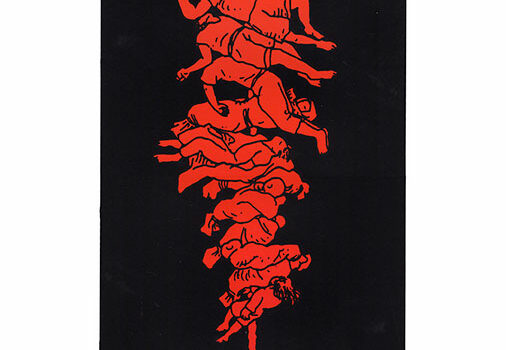

Compare Arnautoff’s project with contemporaneous projects created by Black Harlem Renaissance artists like muralist Aaron Douglas, who painted work to be seen and experienced not just by white people but by people of color. In the latter the works did not shy away from the horrors of slavery and genocide, but they also opened the possibility of a heroic and liberatory future for the oppressed.

Before the hearing, supporters of the mural gave speeches on loudspeakers drowning out an Indigenous prayer circle, and ignored the allies (women) who asked them to hold off until after the prayer circle. It is not a coincidence, I think, that the loudest defenders of the murals, whether leftist, liberal or conservatives, are white men, expressing a sense of entitlement in opposition to mostly people of color with direct experience of oppression and trauma. Erasing the art of a white artist, even a long-dead Communist, is still an affront to the dominant social order. For young progressive activists of color, this leaves a taste of the Left as white (male) historical preservationists.

If our art holds back a generation of students who are forced to experience images of themselves primarily as only passive bystanders in a white man’s world of racial supremacy and manifest destiny, however critical it may be, then perhaps it is time for a new story.

HISTORIC AND LIVED TRAUMA

Murals have a particular power: you cannot avoid them and the story they tell, which of course was Arnautoff’s intention. Murals have to be in public places or even in the halls of power, like those created by Arnautoff’s teacher Diego Rivera’s murals at the National Palace in Mexico City. Evoking the idea that the mural inspires critical thinking meant one thing to the white students who were the primary demographic of the school when Arnautoff forced them to confront the discomfort of Washington’s racist history.

By being so present, so “in your face,” murals carry a responsibility about how they impact those who cannot avoid but see them every day, for whom they will become the markers of the spaces they occupy. The fact that the students at George Washington High School say to each other unthinkingly, “I’ll meet you by the dead Indian” is not insignificant. In passing it every day, the mural normalizes a certain view of history. It’s one thing to experience and reflect upon historical trauma, it’s another to see those atrocities as the visual background to one’s daily life. For some today, the images may provide a critical “teaching moment,” but for others, what remains is simply the white man giving orders to the slave, the “dead Indian” being walked over by the settlers. The mural itself has shaped the space beyond its role as a critical look at history – it is shaping and making the history of the students’ lives themselves.

Listening to and upholding voices who have been historically disempowered does not mean that those communities don’t hold differences of opinion, nor does it mean that a solution cannot be negotiated through a critical lens. A response to the impact of the murals could be expanded curriculum, explanatory panels, or additional response murals created by Indigenous and African American, evolving a new narrative around resistance to Washington’s crimes and empowerment of Native, Black and Brown people. This is the position advocated by Dewey Crumpler, the African American artist who painted the murals responding to Arnautoff’s images in 1974. Back then, the creation of his response mural was the compromise from the School Board to the Black Panther Party’s demand that the “Life of Washington” murals be destroyed.

But I am not the one who has the same historical and lived trauma that these young people today are responding to when they see these images – and neither are most of the writers and commentators in the mainstream media. Arnautoff’s interrogation of history carries with it the primacy of a Western way of analyzing history, subsuming the deeply emotional and traumatic historic and lived experience as “less than” an abstract intellectual frame, an experience the artist and his intended audience never had to live.

Here are a few transcriptions from those who supported the removal of the mural at the School Board hearing:

- “I am Tohono O’odham… We don’t need to see ourselves portrayed as dead Indians every single time. We don’t need that. We know our history already. Our students don’t need to see that every time they walk into a public school.”

- “I’m a licensed psychologist and mother of a Native child who is slated to go to George Washington. My daughter — I just — it makes me shudder to think of her facing these images every day, but I’m here to talk to you as a mental health professional… I’ve been an expert witness in several courtrooms, and everything that people have been talking about here today, tonight about the trauma, about the very real making of invisible, about the impact that it has on our children, is scientifically validated… I want you to know that the mural completely normalizes the colonial image, and they make it as something it’s not. Take it down.”

- “I’m a parent of a child at Souter Elementary in the Richmond district. I never want to hear anyone say to him, I’ll meet you by the dead Indian.”

- “You all come from ancestors that fought so that we could be in this position today. Please let it be unanimous. I know all of you want to paint it down. Go into your heart space. Look at those people. They died. Please don’t make one more student walk by the dead Indians…”

I think the question for us non-Native people should be, how do you respond to that? Do our arguments about the importance of historical art or the artist’s intentions overcome people’s lived experiences and trauma? Are our opinions that much more important or relevant, or “correct”?

AGENCY AND POWER-BUILDING

As a Marxist, Arnautoff might have been proud of how his mural, 80 years after painting it, has stirred controversy across the mainstream media and even gotten the conservative mouthpiece National Review to talk about Washington’s legacy as a slaveowner and Indian killer. As a historical materialist he would have understood how his mural, reflecting the historical conditions of the Depression and the New Deal, is now taking a new life in the demands for its removal, reflecting current struggles that force the state to respond to the demands of Native people.

I was struck by how the articles across the mainstream media, as well as liberal and Right-wing blogs, pointed to the School Board as leading the effort to remove the murals. In fact, the effort is coming from Indigenous peoples, and especially young people. The stories underplay or erase the voice and agency of those directly impacted by the images. And that, in a way, is the crux of the story told by the murals, progressive though they may have been for their era. The murals, despite the intention of the artist, have become a symbol of the shortcomings of how we teach history, wherein the principal narratives around the country’s history of slavery and genocide, when they are even told, are of victimhood, and the role of “great leaders” in moving progress, with little talk of resistance and liberation struggles, and the erasure of ongoing struggles whether on reservation or urban settings.

It’s not a coincidence that the national media has seized upon these murals at this moment, that commentators across the political spectrum have resurrected attacks against “identity politics,” “liberal whites,” and “snowflake” young people, and that they have focused on the School Board over the stories of people’s experiences. The controversy is also about a Right-wing political challenge against progressive communities of color demanding ethnic studies in the SFUSD curriculum and holding off the encroachment of charter school privatization, and specifically against the School Board members they helped elect. The Left loses sight of this at its own peril.

Perhaps Washington’s birthday will one day be replaced with Crispus Attucks Day or Ona Judge Day, perhaps someday we will celebrate as our national heroes Nat Turner, Frederick Douglas, Harriet Tubman, John Brown, Red Cloud, Chief Joseph, or Buffalo Calf Road Woman. We can hope that a new “America” of the future doesn’t continue to just fall back on its tired old white supremacist leaders. Meanwhile, we must do what we can for our new generations of liberation fighters.

As an artist myself, I would like to think that my art could have a life beyond the immediate: art as witness and as historical memory. But as an activist, I hope that my art is most of all relevant: art as a hammer in the struggle, and as healing in our development as human beings and communities with collective agency over our futures. In this case, I’m going with supporting our Indigenous comrades in their struggle from their own experience.

Thank you Fernando, for your thoughtful analysis of the issues. I’m 100 % aligned with your perspective and really appreciate your voice on the matter!

Fernando – Thanks very much for this piece, it is a very good exposition of a complex issue. As a senior gabacho long involved in progressive cultural work I’ve spent much more time listening than speaking about this. I understand that for some people, portions of this mural are genuinely offensive, and no amount of leftsplaining about art history or artist credentials or interpretation will make a difference. I understand that it doesn’t matter to the critics that many people of color have defended keeping the mural. I understand that this is an unusual setting, a semi-public space which young people are required to be in on a regular basis. What I don’t understand is the demand for destruction of the mural.

Given that this giant fresco can’t easily be relocated, and conceding that there is legitimacy to the concerns, why not live with a compromise? I am an archivist, and the first rule of handling unique art is “do no irreparable harm.” Destroying art is a very slippery slope. I support the passion of the opponents, but I stand with the cultural workers of the world who have had their murals whitewashed, their prints burned, and their sculptures smashed in the name of corrective cleansing. Cover up portions (in a reversible manner) if you must, but please don’t paint it down.

You report:

This is the position advocated by Dewey Crumpler, the African American artist who painted the murals responding to Arnautoff’s images in 1974.

But you censor his view, which he held from the late 1960s, and still holds, that it would be terrible to paint over the mural. He worked for years with the students at GWHS and sees both sides better than anyone else.

It seems dishonest to hide his view, in an otherwise mostly thoughtful essay.

Prof. Crumpler’s own words are linked in the article above. Here’s the link again: https://ncac.org/news/art-professor-dewey-crumpler-defends-victor-arnautoffs-wpa-murals.

Despite the author’s good intentions here, there are too many mistakes in this write-up. First of all, there are many First Nations and African Americans supporting the murals and those who are against it are not the best informed and never give an accurate description of the works and the fact that the murals are far more radical than these people, who are in the extreme liberal centre whether they know it or not and who have no proof that the murals have caused trauma to anyone. You can’t compare the Arnautoff murals to Aaron Douglas images because Arnautoff was commissioned to make murals of the life of George Washington, which had everything to do with the Popular Front politics of the time – and given those constraints he did amazing work that very few people have described with any shred of detail. Even Robert Cherney’s book does not go into much detail and so most people do not even know what they’re looking at and talking about. The raised fists of these individuals is a farce when you consider that that is a Popular Front gesture. A lot of people have been talking through their hats on this issue and it’s especially disappointing when it comes from artists and activists with university degrees. The neoliberal members of the Board don’t like the fact that these are leftist murals and that is one reason why they have been more than happy to encourage SURJ and similar anti-universalist types. It’s not about the Right and progressives. It’s about the Right, the Neoliberal centre (with its identitarian agenda) and the almost nonexistent left. It’s not the left that is losing sight of this if you have been following the online articles on WSWS, Nonsite, Indybay.org, Jack Heyman’s article on The Internationalist and Laborvideo’s youtube postings, its sites like Hyperallergic, The Nation and Medium who are too woke to take a clear stand against the kind of fascist logic that understands art and politics according to racist classification. Post-structuralist social constructionism and decolonial anti-Enlightenment is making it such that people are becoming more than happy to allow the Right to define the terms of universality and are mired in materialist and identitarian reductionism – as well as the opposite – the privilege, for what’s it’s worth, which is not much, of fancying oneself the non-discursive outside, which has more to do with victim politics than solidarity. So decolonial attitudes are blending with the kind of neoliberal charterization promoted by several Board members and the SFUSD superintendent, as discussed at this recent meeting: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iVF0eDdK5iw&feature=youtu.be

“Sequential art also helped solve the problem of how best to communicate the historical indignities suffered by union members without resorting to pitiful images of worker passivity and victimization, against which many artists on the left had cautioned since the Popular Front era. As [Rockwell] Kent wrote [Giacomo] Patri in a 1941 letter, ‘Workers have agony enough without being reminded of it on their walls.'”

As quoted in ‘Graphic Consciousness: The Visual Cultures of Integrated Industrial Unions at Midcentury’

by John Ott, American Quarterly, 66(4) December 2014

You could replace ‘workers’ with ‘indigenous people’ and have it be about this mural. These are old debates, it feels like there’s some relativism within the arguments for preservation, that seems to put forward that times have changed, and the political landscape from where this artist worked isn’t translatable.

This is the most balanced presentation of this controversy that I have seen. It’s also one of the only articles that includes the fact that this is the muralists colonial viewpoint, not history