My friend Eric Triantafillou, a teacher, artist and designer in Chicago, has been following all the dialogue around the Shepard Fairey controversies, and wrote up the below piece in response. Check it out:

Shepard Fairey: Sideshow; Shibboleth

Eric Triantafillou

I’ve been following the debates around Shepard Fairey for the past couple years and finally decided to respond with some of my own thoughts. I want to start by briefly mentioning an encounter I had with Fairey in San Francisco back in 2000.

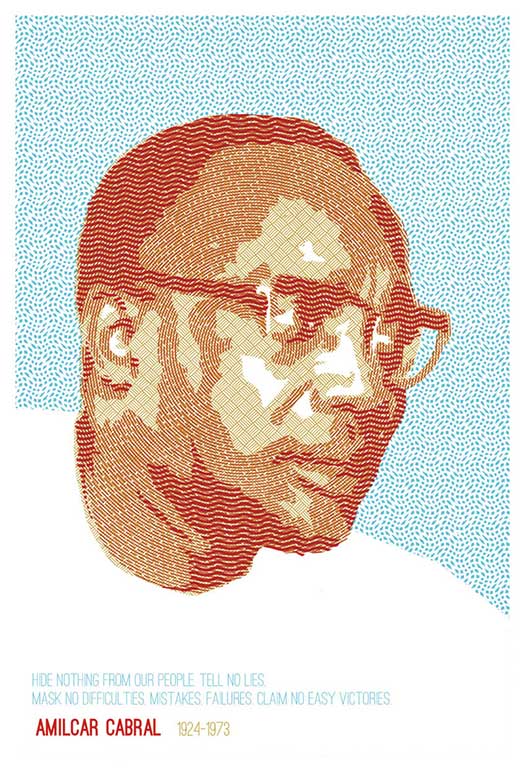

It was during the height of the dot-com induced housing crisis that was forcing thousands of (mostly Latino) residents out of the Mission District. One night some friends and I were out pasting up posters for an anti-gentrification rally at City Hall. On the vertical supports of the Highway 101 overpass were Fairey’s long red banners with the Andre/Obey/star motif in a circle. The circle was the same size as the round black posters we were putting up, so we pasted one on each banner. They looked really tight together. I didn’t realize it at the time, but a lone Shepard Fairey was working just few steps ahead of us. He must have seen our handy work because minutes later he pulled up alongside us in his SUV, honking and yelling “Hey! What the fuck?!” I was thrilled. I had always thought Fairey was a sellout and now was my chance to confront him on common ground. I detested him less because he “steals” other people’s images and more because he seemed to have no regard for the spaces and places he puts his stuff up. Here he was, obliviously working away in the middle of a neighborhood that was socially hemorrhaging. To him it was just another space, an empty canvas on which to point out what advertising had long since proven. So add to the gripes that his work whitewashes history (time) by unhitching social struggle from its representational forms, the fact that it also has no relation, except on a purely formal level, to the space it occupies. Space for Fairey is simply a backdrop. When we pressed him about this he said that all the space around us is there for the taking and that we, as fellow street artists, should know better than to paste over someone else’s work; that we all know how much time and labor goes into making and putting it up. Aside from his idea of street art as a kind of Manifest Destiny, we agreed that it’s hard work but said that it also requires a degree of mental labor, and maybe his work would really take root if it reflected something about it’s environment, like a connection to an existing social movement; a commitment to something greater than himself. He didn’t get it. Instead of haranguing him further, we left to finish our work.

My interest in recounting this moment is not as a window into Shepard Fairey’s self-understanding but my own at the time and how it’s changed since. So much of what has been said by Fairey’s detractors is about questioning his intentions or about holding him personally accountable. It’s been said in various ways, and it sounds like many of us agree, that Shepard Fairey is a symptom of a far deeper malady. I think if we look at Fairey as a symptom rather than a cause, as Josh did in his post, it helps reveal how our discontent with the system, this includes the histories of struggle that Fairey poaches from, is made part of the dominant ideology. I think these discussions would benefit from addressing how the socio-economic system we all live under is able to reproduce the Shepard Faireys of the world AND his dissenters (us: Left artists), generation after generation, without a serious challenge to its hegemony. Here’s how Josh finishes his post:

“His work will only be successful (at more than making money) when he cites his source materials and tries to cut through the amnesiac haze of our society instead of adding to it. When a Fairey wheatpaste on the street becomes not an advertisement for his clothing line but a site for arguing over how we fight and struggle in this world today, I’ll be the first one to send people out to look at it and argue about it.”

As far as I can tell, Shepard Fairey’s practices have managed to generate a pretty vibrant conversation on this site and elsewhere. It remains to be seen if these arguments stay mired in issues of fair-use, theft, and Fairey’s self-promotional motivations, or develop into more fundamental questions about “how we fight and struggle in this world today.” I would add that a big part of “fighting” and “struggling” is thinking. I can only hope these conversations expand to include questions about our own political consciousness.

In that spirit…

Does anyone really think that if Shepard Fairey credited his sources the steamroller of historical amnesia would break down, or even slow down? Anyways, wouldn’t he just use mouse type, like pharmaceutical ads? And we know no one reads the small print because everybody’s taking the pills. Maybe we should thank Fairey instead of chastising him. Maybe he has, in spite of himself, helped realize the project the Situationists began back in the 1960s of exposing how images in a capitalist society comprise a surplus, like any other commodity. The Situationists thought the only way through the commodity form was not by resisting it, but by fully realizing it. To achieve this, they took plagiarism to new heights. But then they didn’t privilege an image of Angela Davis as having more revolutionary potential than a cheap porno flick. To them it was all fodder for the spectacle, and all artists could do in a mature commodity society was expose the increasing gap between reality and illusion by pointing out how the illusion is continuously reproduced, not by pointing only to its symptoms: corporate greed, white privilege, etc. The idea was that if people confronted the totality of commodity production under capitalism, both objectively and subjectively, they would overthrow the commodity-producing society once and for all. The Situationists believed the realization of image as surplus could help expedite this outcome. Their project eventually collapsed under the weight of its own demands. I don’t think it matters much whether we think everything under the sun is commodifiable or not. There is an extremely powerful system that makes commodities out of human relations in order to trade them on a market, and this system seems all but impervious to attempts at reforming it.

A few years ago I would have cheered Mark Vallen when he writes in his post that Fairey “toys with the veneer of radical politics, but his views are hollow and non-committal.” I would have been the first to agree with Favianna when she accuses Fairey of being a pawn of elite media, and of being “unethical.” These comments sum up how a lot of people in this discussion feel about Fairey. After years of making similar indictments myself, it slowly began to dawn on me that this finger-wagging, contrary to achieving any results, functioned as a kind of holier-than-thou Left posturing, something I did to assuage the sense of utter helplessness I felt when confronting what it would take to really transform society. It made me feel like I was better than others because I care and they don’t. Rather than encouraging me to reflect on the efficacy of my own practice, this postering simply served to re-affirm whatever I was already doing, in part because others around me were doing the same. It was an uncritical, crowd mentality.

Is Shepard Fairey “non-commital” and “unethical?” Sure, I guess. But what does this mean? Bound up in these statements is an entrenched liberal ideology that maintains rather than challenges the status quo. It sounds a lot like when Obama calls the Wall Street execs that gave themselves $20 billion in bonuses of taxpayer money “shameful.” This is a ‘Get-Out-of-Thinking Free’ Card. It places all the emphasis on an individual’s decision to do “good” or do “bad” within the existing system. It says: the larger socio-economic structure is not really the problem. The problem is a few bad seeds that spoil the lot. This amounts to an implicit endorsement of a system that produces the very social conditions under which a few are able to dominate many. These statements make Obama sound righteous, just, fair—qualities that appeal to and affirm our sense of morality.

I’m not against linking ethics with politics. I just think that ethics cannot be the foundation of an anti-capitalist politics because acting ethically is easily folded into capitalist logic, generating what should be some glaring contradictions. Take an organization like Amnesty International, whose strategy is largely the mobilization of shame. They have had some success using tactics like inundating a Colombian paramilitary general with letters sent from people around the world asking for political prisoners to be released. At the same time, they harass various states by constantly calling on them to abide by established human rights law, but also to adhere to the Geneva Conventions, which are essentially a set of rules for how to treat people in war. Think about that for a moment. An organization that represents the apex of contemporary morality makes appeals to various powers, asking them to adhere to an internationally ratified set of rules for how to ethically kill people.

I realize that we live in an imperfect world and that without these organizations and laws, the conditions for many people would probably be worse than they are. I’m not advocating we shut down Amnesty, or similarly, that artists stop talking about commodification and forego pursuing legal action. It’s their choice how to deal with their grievances. And there’s a certain degree of empowerment in using existing legal and moral structures. My concern is to make sure these appeals—as forms of liberal politics—don’t end up compromising more radical politics.

I think we all know that after some technocratic tinkering around the edges, a tighter regulation here, a temporary executive compensation cap there, the underlying causes of the financial crisis will remain in place, guaranteeing the next crisis. Even the focus on crisis as the engine of capitalist development implies a politics of planning that shuts out possibilities for a more fundamental anti-capitalism. People say: if the system were set up better, if there was a more equitable distribution of wealth, this wouldn’t have happened. It’s no different with copyright infringement or intellectual property rights. Taking legal action against Fairey may put a few dollars in Mannie Garcia’s pocket (the AP photographer who took the Obama photo he used for the Progress poster), and may help deter the Faireys of the world from appropriating other people’s work, or at least get them to credit their sources. But let’s be honest, it doesn’t address what’s generating the conditions of perpetual social conflict as much as it attempts to mitigate their effects.

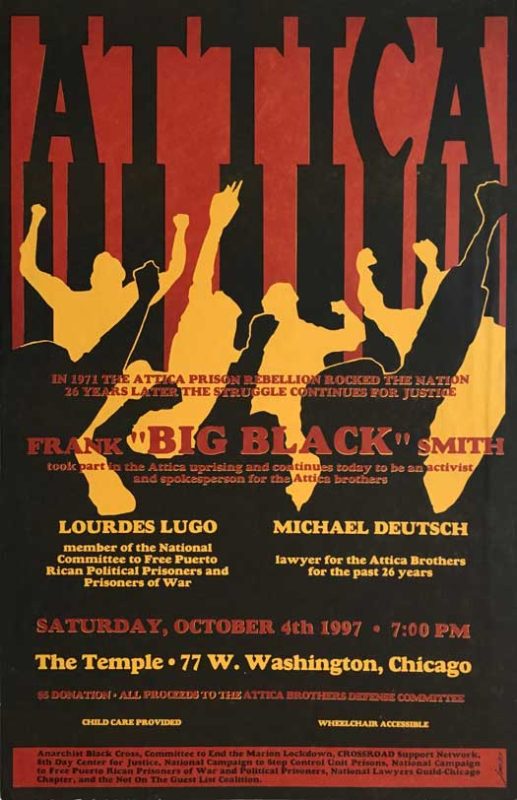

What is the radical history of struggle these protests of Fairey’s collusion with “elite” media are attempting to uphold? Angela Davis wasn’t fighting to preserve affirmative action. Che Guevara didn’t go into the Bolivian highlands to seek compensation for copyright infringement. As misguided as his Bolivian campaign was, he’d set his political sights higher than intellectual property rights. As I see it, part of the problem is that there is no unified opposition to capitalism in this country. Critiquing Fairey from the standpoint of liberal democracy (I’m ethical, he’s unethical; I’m altruistic, he’s greedy) is a lot easier than articulating and organizing an opposition to a system that perpetuates the social conditions that make things like poverty, injustice, racism and historical amnesia possible.

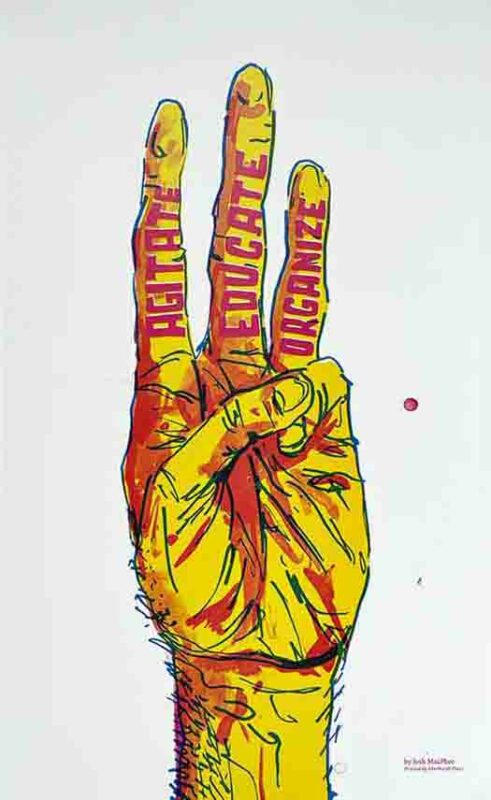

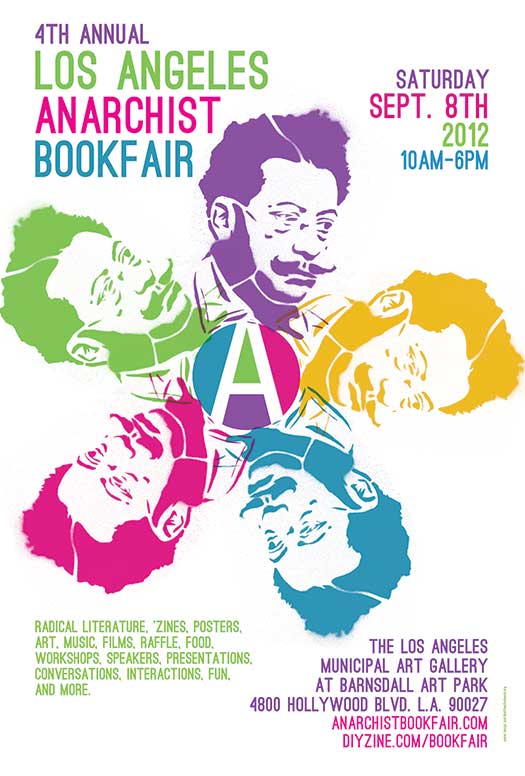

Do we really want to spend our time policing the Shepard Fairey’s of the world? Let’s bring the focus back to ourselves, to the self-identified Left. Let’s look at our own work, investigate our own intentions; our consciousness. Let’s try to understand better how images become autonomous from human beings, and as social relations between things—as commodities—are able to have so much power over us. Let’s talk about the ways we produce work in service of social movements and the politics of those social movements. Let’s allow these debates to be more theoretical without forcing them into immediately actionable ideas. Let’s make these conversations just as much a part of our practice as the work we make and disseminate. Maybe then we could stop repressing the painful fact that a well-organized anti-capitalist movement doesn’t exist in this country, and instead of lashing out at symptoms, we could begin to build one.

I’m a fairly well-educated, privileged person who didn’t go to college (I’m not bragging or complaining just setting out the facts), but when I read critiques like this it just makes my head spin. Half the time I don’t understand the point and the other half I’m like, who cares?

I’m down for a more vigorous internal critique in the left or the movement or whatever, but this sets up a false opposition, that says Valen or Favianna by critiquing Fairey took their eye off the ball, and that this writer got over his finger-wagging days a few years ago and is back at systematically destroying capitalism (where we all should be).

I feel like I understand the limits of personal and identity politics, knowing that political movements have to larger and more militant goals and strategies. But also I feel like there’s a real value in politics that allow you to face yourself in the mirror everyday, whether that’s not wearing orange, or dumpstering, or treating people with respect or in this case calling out Shepard Fairey as a douchebag. This value is not quantifiable.

And the flip-side of that is knowing the limitations of those choices, that most likely these actions don’t mean that much to anyone but ourselves.

I don’t feel like critiquing or questioning this stuff has taken away from anyone’s activism or discourse or whatever.

The situationist critique makes sense to me, but ultimately isn’t it completely cynical? Prius can take a Public Enemy or Minutemen song for a commercial but does it take away the power of that song? the mere fact that it can be commodified? I think it’s interesting that Fairey’s image of Obama is powerful (much more so then the original photograph), and it’s massive bootlegging is proof of that. It’s probably also one of the least derivative images I’ve seen by him.

Scattered thoughts from a scattered guy.

That is quite an interesting take on Fairey´s work and his repercussion. I am somewhat in a contradictory position, similar to the one that Favianna expressed in a previous post. Most of those considerations aside, and almost Fairey aside, I’m not too comfortable about a compulsory obligation to recognize sources, and define meanings when one contributes in cultural production. I actually try to do it most times, but on occasion I also feel that a level of ambiguity is desirable and stimulating. I prefer to think of “critical” ambiguity, one that generates a dialogue, is part of a process and offers a chance to weave and transform different takes. Now, Fairey´s ambiguity plays distantly with some of this, not brilliantly, but it does. One of the biggest problems is that when he is exposed as figure, as that referential genius, he is non-committal, hides away from questions, brushes off actual activism, and plays quite a predictable and trite role, more so lately. On the issue of ambiguity, expanding meanings, and anarchist stimulation Jeff Ferrell had quite a good section in “Crimes of Style”

Now on the concern expressed by Icky I understand and like most share to some extent the comforting need to try to think that my behavior is or tries to be moral in itself, which helps me to live with me or to look at myself in the mirror. But like Eric points this attitudes offer little opportunities for change, at least I would add, in a way that does not play a complacent role with individual ethics as opposed to world ethics. Like some critical philosophers I think that there is quite a bit of uncomfortable circumstances in facing the dilemma that if the world we live in is structurally unethical, whether we conduct ethical lives is irrelevant, what would be relevant would be to find the means to make the world an ethical place (Fernández de Liria for instance argues around this line of thinking)

Cheers,

Daniel

Sounds like two self-important douchebags calling each other douchebags.

I think the biggest problem we face as political artists is finding a way to produce work that cannot be coopted by capitalism to recouperate method. And when a capitalist mind encounters work that does that, it needs to go down like medicine.

I have no problem with image influences, sampling, or re-using commercial art when the re-use is barely recognizable or there’s no profit theft from the original artist. Fairey’s cooption of revolutionary art would be fine if he reused it with the revolutionary/social-change intent of the original. Unfortunately, even in his own words, he’s just out for the fame and fortune. His work shows the hand of a skilled artist but his intent is just another commercial for self-agrandizing greed.

I think it’s fine, and even mandatory, to out the guy’s work, because once you hear the medicine it’s clear to see that his work is just a factory of phony crap. And who wants to wear or hang phony crap? Fairey’s brilliant Obama poster that images our phony hero (as time has proved both of them to be) while stealing copyright profit from another corporation, is greedy commercialism at it’s best. The only thing more synergistically capitalist would be a Fairey portrait in the ‘Bama style!