For many Indigenous people, late-winter or early-spring (depending on your perspective) is the time to be in the Iskigamizigan or Sugar Bush. It is a period when everything and everyone slows down. It is a period when we spend time together. As I have discussed in my own writing and arts practice, visiting is an Indigenous methodology. This is something I have learned from the elders – people don’t visit anymore. As such, we must intentionally create time and space to visit and share and learn together. By creating a time and place – in this case in the Sugar Bush – we can radically oppose the heightened pace of capitalism through our own quotidian activities and the collective time we spend together outside the confines of wage labor.

In the Sugar Bush, we meet up with friends and family to reconnect. With snow still on the ground, it is time to share stories and collectively prepare for the coming spring. It is a moment to rejoice in the returning sun – in Michigan, we are hopeful, but will likely wait a few more weeks. Pretty soon, the snow will melt, the spring peepers (Pseudacris crucifer) will return, and the rain and thunder will be back.

Unfortunately for us in Mid-Michigan, I heard the spring peepers in February and the thunder beings came shortly after. When I heard the peepers during this period of records highs, I was saddened, but not shocked. As you can see from the images taken this past weekend, there was no snow on the ground during our time in the sugar bush. Although it is back to below freezing temperatures, the early warms have melted all the snow. When I woke up with morning, however, I was happy to see a fresh dusting of snow and we are expected to get up to six inches.

Here in Nkwejong – what many in Lansing’s Native community call this place – we are currently hosting our second annual Urban Sugar Bush. We call it the Urban Sugar Bush because we host the event at a city-owned park and nature center in the middle of the city. During the sugaring season, we gather for a series of weekends to boil sap. During the week, people watch the buckets and then harvest the sap once buckets are full.

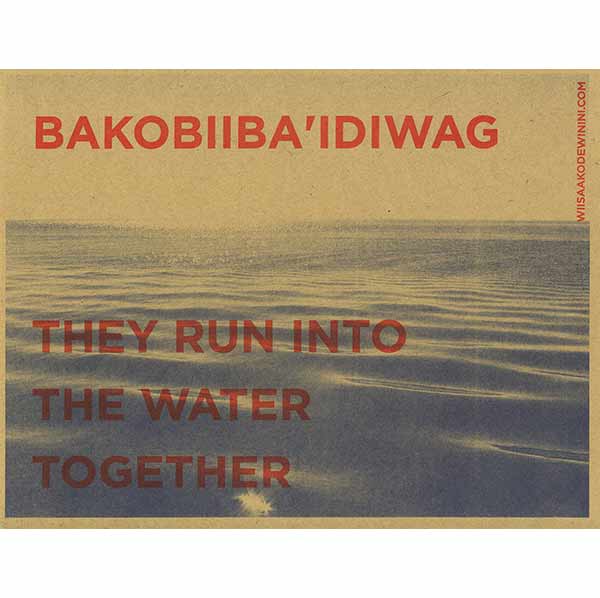

Lansing is the state capital of Michigan. It is a post-Industrial city with a metropolitan population of half-a-million people. Like many other rustbelt cities in Michigan (Flint, Saginaw, Kalamazoo, Detroit), the city itself has seen its population fall slightly as it tries to reconcile a future in a state that is now a ‘Right to Work’ (that is anti-union) state. Historically, Lansing has been an important visiting place for Indigenous peoples from across the Great Lakes. It is situated in the middle of the lower peninsula and along the shores of the Grand River at the confluence of the Red Cedar River. The name Nkwejong refers to a place where the rivers meet. We can also think about Nkwejong being a place where humans and other beings also meet. It is part of the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw and the city next to East Lansing is Okemos, named after an important Ogemaa or chief.

In the Western or Minnesota dialect of Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe), the lunar month that begins April 11, 2017 is known as the Iskigamizige-giizis (Sugarbushing Moon). The Eastern dialect of Anishinaabemowin (Odawa) does not use this term, as I understand it, because of different harvesting cycles. In both Eastern and Western dialects, the month that begins in March is known as the Snowcrust Moon – Onaabani-giizis in the Western dialect and Onaabdin-giizis in the Eastern dialect. With the eminent changing climate, it may become necessary to rename months as their relationship to Indigenous ecological knowledge is disconnected from the activities that happen during that month. An elder once told me that Bootaagani-minis (the place where wild rice is milled, now known as Drummond Island) should more aptly be called the place where wild rice was milled. Colonization and ecological change is having swift and long-term impacts. So, it becomes all the more crucial for us all to gather in the Sugar Bush. Here, we can learn together; we can share together. We can collectively laugh and mess things up together. We can be called out for things we do wrong and acknowledged when we do them well.

For the sap to run, you need above freezing temperatures during the day and below freezing temperatures at night. The bigger the variation between night and day, the more quickly the sap will run. If you tap a tree on its’ south side, you can insure that the sun will also warm the tree, assuming that we get sun in Michigan.

The sugar in maple sap is the product of photosynthesis and, generally, sugar maples have a higher concentration of sugar than other trees. It takes about 40 gallons of sap to produce a single gallon of syrup. To increase the sugar content you need to boil off the excess water off. Of course, another way is to allow the sap form a layer of ice, which will not include the sugar, and then discard the ice. As I’ve been told, this was one of the ancestral technologies to make syrup. Eventually, however, the maple tree will use the sugar in its’ sap to make buds. Once this happens and you notice a green canopy, the sap you harvest will be bitter or ‘buddy.’ Knowing the when to harvest sap is about understanding where you live and your community’s climate. Iskigamizigan is about responding to one’s local environment and getting to know the trees and the seasons.

For two days this past weekend, we boiled sap on a wood-burning evaporator. Ideally, once you start boiling sap you should just camp out in the Iskigamizigan and boil all night long. However, with everyone’s familial and community and work responsibilities, we only boil about 6-8 hours at a time. This seems to be the threshold that commnity members can commit. At the Jijak Camp run by the Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi (often known as Gun Lake), they run a wonderful low-production commercial operation. Many other Indigenous communities, such as Pokagon, also do community Sugar Bush activities. On social media, it is fun to watch various communities and community-members disappear into the bush for their own sugaring activities. As an urban community, we are attentive to making the activities open and accessible. You can even get to our Sugar Bush on a paved path or we can drive elders in a vehicle.

While in the Sugar Bush this past weekend, the temperature hovered around 25 degrees. Because it was below freezing, the sap wasn’t running. It should return to the upper-30s by this upcoming Thursday and, once again, we should again see the sap run.

As you’ve also likely experience, we’ve had some crazy weather this winter in Nkwejong and so the sugaring season is difficult to pin down. In February, temperatures reached record highs and peaked in the upper-50s and lower-60s. At that time, at least a month early, the sap started running. With our current state of shifting temperatures and changing climate, it is becoming difficult to know exactly when the seasons will happen. The traditional Indigenous knowledge that linked activities to the seasons and calendar are continuing to change at an increasing rate. In turn, just as our ancestors responded to colonial and capitalist incursions, we too must response to the new timeline and to erratic weather patterns. Will language speakers create new words for things? Will practices go dormant with dwindling access and species extinction? Will we need to create a new calendar that describes when the berries and manoomin and sap are to be harvested in the future? Will February become the new Iskigamizige-giizis (Sugarbushing Moon)?

While we use many commercial technologies in our Sugar Bush – such as a Leader evaporator and wood fired arch, as well as metal spiles and galvanized buckets – we also try our hand at making of our own supplies and integrating ancestral technologies, as Sacramento Knoxx called them this weekend. As such, we created our own sumac spiles and birchbark baskets, from bark I harvested last summer (and wrote about here). At the suggestion of Lee Sprague,former ogemaa of the Little River Band of Ottawa, we crafted some traditional tools from cedar last year in the Sugar Bush. We use these tools to check the density of syrup. These are some more ancestral technologies. As time goes on, we learn from and with these materials and technologies.

While we still can, we decided to make wooden spiles – the spigots used to tap maple trees. Traditionally, staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) has been used to make spiles. Some people also used maple saplings, but I’ve always used sumac. On Friday, I harvested a few branches of sumac, which grow about a five minute walk from the Sugar Bush. They are located in the middle of a reclaimed native prairie.

Staghorn sumac has a very soft pith (center), which can be burnt or poked or drilled out easily. Traditionally, staghorn sumac was also used as a pipestem. We spent a few hours whittling spiles and poking out the soft pith of the sumac twigs.

In the summer, sumac also makes a wonderful tea. In this picture from last summer, I dried sumac on a cattail mat that I wove one weekend in August.

While harvesting the sumac, I encountered a raccoon skull, jawbone, and teeth. I offered some semaa and kept these, as well. I am sure at some point they will be turned into beads or something else.

If you are around Mid-Michigan, we will be back in the Sugar Bush over the next couple of weekends. We do not make a lot of syrup, but that isn’t the point. It is about gathering together, visiting with one another, and communicating with the trees and spirit of this place.

Gamaamiikobiige n’wiijii- You wrote it well my friend.