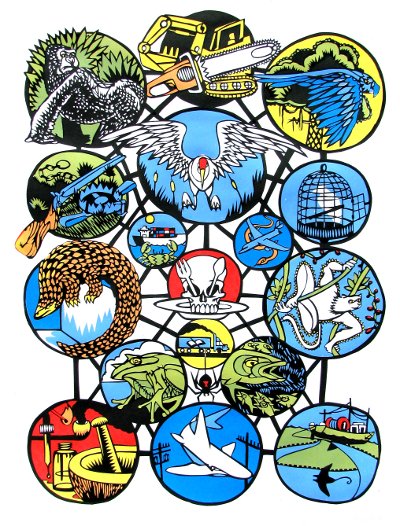

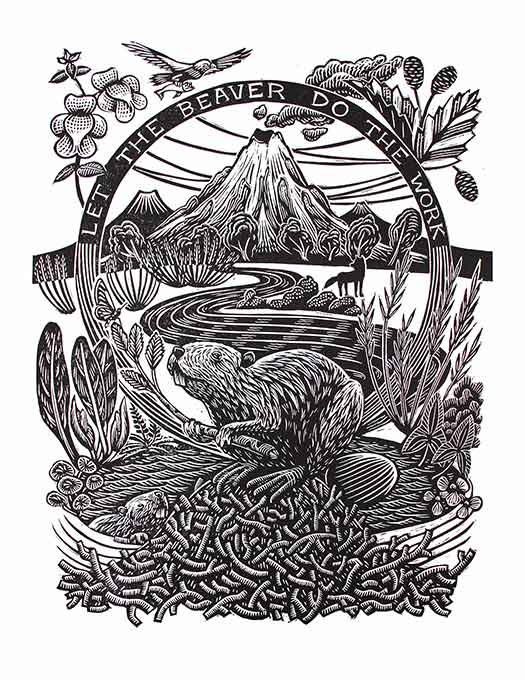

I recently completed this new print, entitled “The Process’, which is now available in the Justseeds store. It feels like something I’ve been trying to make for a long time, and the process of creating it was immensely satisfying. It incorporates many visual ideas that have been paddling around in my notebooks for years, looking for a home, and does something more: it provides a framework through which to tell a multiplicity of stories.

(View larger image)

The point of biodiversity is that it is complicated. Everything alive is leaning on everything else, exerting pressure, withstanding pressure, swaying like limbs in wind. Life in our cities and towns is so simplified, so basic, so free of the beauty and complexity of life that we have essentially lost all relationship to the world of biodiversity. At this point, its complexity and richness just alienates us, in large part because it implies an astronomical quantity of priorities that are at odds with our own. As humans, and especially as humans within this groaning, creaking hulk of industrialized civilization, we exist now only to propagate our ideas about the world. We are no longer a part of the world: the world exists now mostly within the human brain. We have been loosed from the tethers that keep every other living thing swaying smoothly in the gales, and the upshot is our descent into the realms of pure abstraction, pure thought, pure culture. Much as we long for a connection to the real world, for most at this point it is impossible. Why? Because we’ve upended the gamefield, and everything is up in the air. Places we see as emblems of natural beauty are in fact deeply impoverished, and everywhere all is falling further into tatters. We know no plants, no insects, no animals, and only our specialists and the curious few exhibit any curiosity towards the actual relationships that create the world. Our tragedy is that we constantly misperceive the frayed nature of this world we’ve made. We tend to see our environment as a thing that is whole but under attack, and seldom realize the damage already done. Our children will thus come to see the ash and corpses of their youth as the greenest playground they will ever know: they will build their definitions of ecological balance and beauty on that baseline. In this manner, for thousands of years, we’ve been working our way towards this contemporary frenzy, where all around is the rustle, roar and murmur of human thought and hunger, and everywhere the world of the non-human is in vast retreat.

This print is an attempt to describe the interlocking mechanisms through which human culture has brought forth this era of mass extinction.

a) Deforestation: When forest land is cleared for agriculture, mining, or settlement, species are displaced and ecosystems destroyed. Road-building is the spearhead, opening new territories to floods of destructive human activity. Human development and expansion has fragmented global forests into poor islands of degraded habitat that shed species as they continue to shrink. Although historically driven by the subsistence farming practices of the very poor, deforestation is now largely the fault of resource-extraction corporations.

b) Mountain Gorilla: One of our closest primate relatives, the Mountain Gorillas of Central Africa have seen their habitat whittled to a fraction of its former extent by human encroachment. Poachers target them for their meat, and they fall victim to snares intended for other animals. The encirclement of their habitat by agricultural lands brings them into direct competition with farmers for the food being grown.

c) Spix’s Macaw: Restricted to an inhospitable semi-arid zone in the Brazilian state of Bahia, the Spix’s Macaw is a large blue parrot that is currently considered extinct in the wild, with about fifty remaining in captivity. The bird’s population was obliterated by trapping for its glorious plumage, coupled with the destruction of the riparian woodlands in which it lived. Invading Africanized bees also competed with the macaws for nesting sites, often stinging birds to death.

d) Hunting and Trapping: Guns, steel traps, wire snares, poisoned bait and trip-cages are used all over the world to acquire animals for food and sale. Many trapping methods mutilate and kill animals for whom they aren’t intended; poisons do the same. Demand for bushmeat drives a growing global economy in forest foods, pushing market hunters further into forests in search of scattered remnants of animal populations. The global annihilation of large predators has seriously disrupted and destabilized most of Earth’s ecosystems.

e) Whooping Crane: North America’s tallest bird, the Whooping Crane historically inhabited wetlands, marshes, mudflats and wet prairies throughout the Midwest. The wholesale conversion of those habitats to farmland throughout the twentieth century brought the bird’s population to a low of 15 birds in 1941. The Crane has rebounded slightly since, but its habitat continues to vanish.

f) The Pet Trade: Hundreds of species of birds are trapped out of the world’s forests to feed an apparently bottomless human enthusiasm for caged units of beauty and song; birds also trade as symbols of status, and, in the case of the rarer species, as objects of speculative investment. Mammals are also sought, as well as reptiles, frogs, snakes, spiders and other arthropods, and fish. The pet trade, and its associated trade in animal parts and feathers, has contributed to enormous losses worldwide during the past 150 years.

g) Pangolin: Pangolins are tropical anteaters of Africa and Asia, up to three feet long and covered in hard, fingernail-like scales. They are hunted for bushmeat in both regions and are traded in industrial quantities to China for the alleged medicinal properties of the scales: numerous shipping containers packed full of pangolins and other creatures have been intercepted in recent years. Massive deforestation in all parts of their range has caused the numbers of all pangolin species to plummet.

h) Hunger: At the heart of all human activity lie the two central motivating forces of all biology: the need to reproduce, and the need to feed. In the grim aftermath of the Green Revolution, swollen human populations are being pushed, by poverty and desperation, back and forth between swarming cities and fringe lands. At the edges of society the raw need of hunger brings humans a stark choice when faced with ostensibly protected lands and creatures: poach, or die. Such choices eventually form an economy of their own.

i) Invasion: The advent of mechanized transport has created a situation on Earth unknown in scope in the entire history of life. The species of the world are being shifted about in incredible quantities, in terms both of the number of individuals and the species themselves. Displaced, and suddenly liberated from both predators and disease, many of them are erupting into new ecosystems like biotic volcanoes. Species have always moved, but in the modern world they move en masse in millions of gallons of bilge-water in supertankers, or mixed in with cargo and superstructure of fleets of commercial airliners, trucks, and freight trains. Intentional introductions of exotic species have had apocalyptic unintended consequences: the trend is towards a universal ecological imbalance. The three invading species depicted here are: 1) the European Green Crab, conquering ocean bottoms worldwide, 2) the Brown Tree Snake, responsible for the destruction of almost all of the native vertebrate species of Guam, 3) The Redback Spider, an Australian relative of the Black Widow, now spreading across Japan.

j) Silky Sifaka: In scattered forest fragments on the island of Madagascar, Silky Sifakas cling to a diminished existence. The large, white lemurs suffer from the aftereffects of massive deforestation through illegal logging and swidden farming, and face the added threat of plans for large-scale industrial agriculture. They are not, unlike many other species of lemur, subject to taboos against their consumption; they show up to market smoked, piled in wicker baskets.

k) Palawan Horned Frog: Worldwide, frog populations are falling victim to chytrid fungus, an exotic invader that has already caused several frog extinctions. The Palawan horned frog, its numbers in freefall after the deforestation of its island habitat, has yet to fall victim in large numbers to the fungus, but the leveling of further forestland for mining and crops brings development, roads, humans and the chytrid closer every day.

l) Menhaden: This small, bony, intensely oily fish is considered by many to be a keystone species of the Atlantic coast ecosystem of North America. Filter feeders that move in shoals so big that they resemble islands, Menhaden clean the superabundance of algae from estuaries and coastal waters and transform it into oily prey for big populations of predatory fish and scavengers. The exploitation of Menhaden schools for cheap industrial oils and meals has caused many coastal ecosystems to break apart. In the wake of the industrial fishery floats a red tide of uneaten algae that deoxygenates the water and creates dead zones that stretch out into the open ocean.

m) Traditional Medicines: In South Africa, gamblers smoke the brains of Cape Vultures for inspiration. Enthusiasts of Chinese medicine pay premiums for patent medicines made from Tiger bones, Bear bile, and the horns of the last few Rhinoceroses on the planet. Diminishing wild populations couple with spreading beliefs and new money to create new markets. Well-intentioned suggestions for substitutions to the consumption of rare animal parts for this purpose have led to localized extirpation of the substitutes, such as the Saiga antelope of East Asia, whose horns were touted by western wildlife NGOs as alternatives to rhino horn.

n) Ganges Shark: This six-foot-long freshwater shark inhabits rivers, estuaries and lakes in Northeastern India, surviving mostly on small fish and carrion. The global demand for shark fins and products has driven many shark species to the vanishing point, the Ganges shark no exception to that rule. In the absence of predators such as this and other, larger, fiercer sharks, the ladder of life in the oceans collapses under a thick slime of algae, jellyfish, and bacterial mats.

o) Overfishing: All life emerged from the ocean, and, in this era of global mass extinction, humans have been intent on hauling as much as possible of the life that remains there onto the land. Industrial fishing techniques such as the purse-seine net and longline have ended fish stocks in fishery after fishery in all of the oceans of the world, and a growing human population clamors unceasingly for more. The nets and lines doom not only schooling fishes, but anything within reach of the net or with an appetite for one of the millions of baited hooks. Fish considered trash a generation ago are now delicacies, because they are essentially all that is left.

Wow, don’t know what more to say after reading this.

This is explained so well and incredibly executed.

Congratulations on pulling this print together!