They want our home. Our home. For themselves. They think they have a right to our home simply because they have more money.

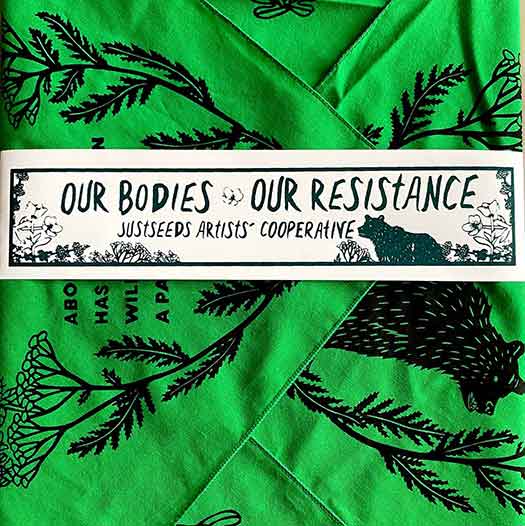

We are fighting it. The buyers knew what they were getting into when they bought our place. We hung posters I had designed for the Tenants Union on the front door and all over the apartment. Those posters are still here. “This is our home. We are organized. We will fight. We are not leaving.” We handed each prospective buyer a letter as they came in, before the tromped through our living room and kitchen and bedrooms: “Welcome new landlord. We know our rights as tenants. We intend to stay.” We asked them in turn what their intentions were, and they simply answered, “we don’t know.” Yeah, right.

The evictors like to stay hidden, out of the limelight. Our evictor’s name is Tatiana Omran. She is the one who can call it off. The building was bought by Tatiana and her parents, Peter and Tanya Omran, and court papers show that Tatiana owns 25% share. Tatiana’s parents run a non-profit aid organization Heart of Mercy International. The brothers, Michael Omran and Christopher Omran, run Abana Coffee and Portal Avenue Coffee.

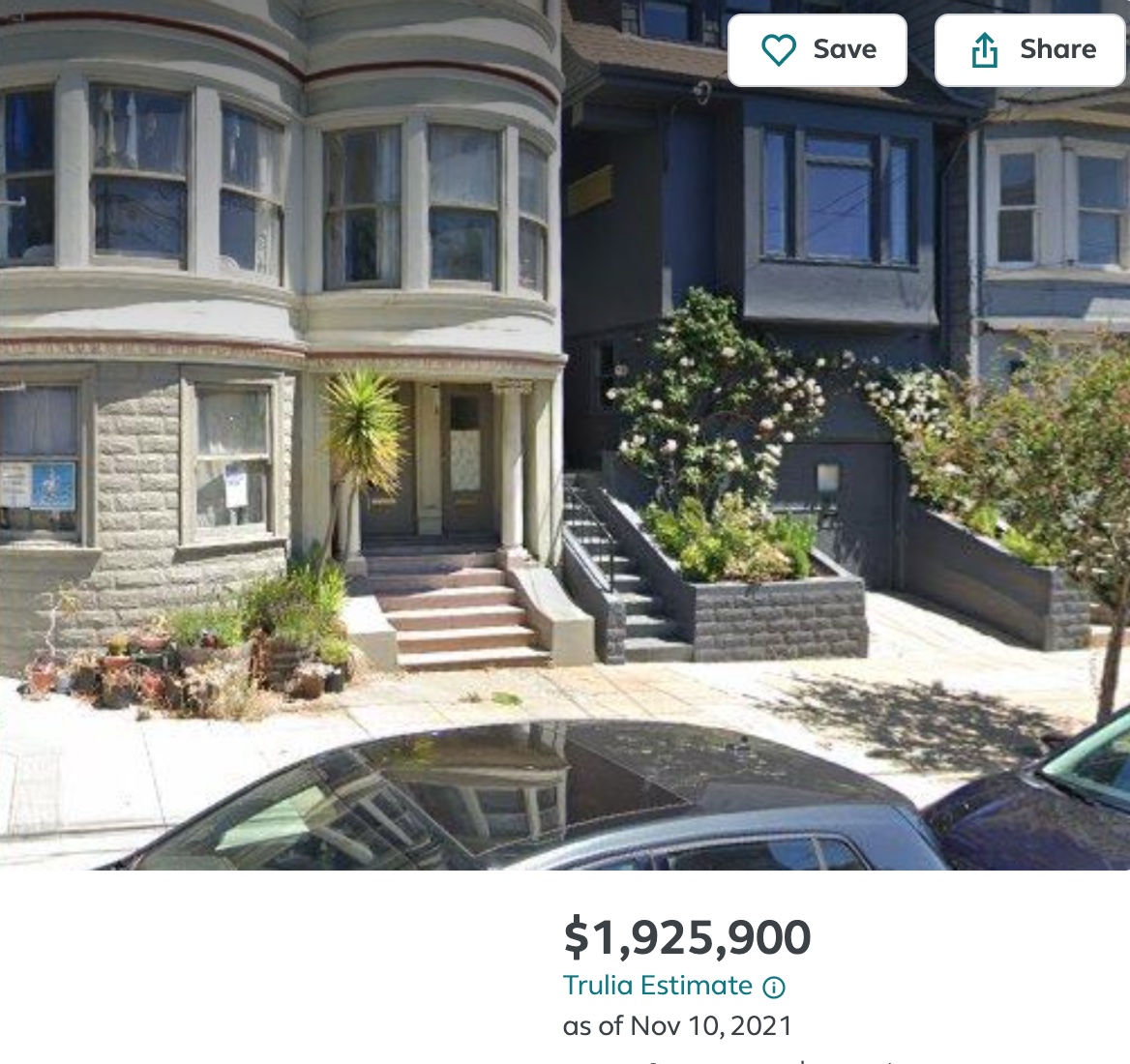

To them, our home is only some square feet of space with a price tag attached. To them it’s all speculation: buy cheap (because there are tenants in place), get rid of them, sell high. As our friend told us, “Doing tenant counseling, you get a window into all the ways that greed manifests in our society.” As though people’s homes are just play pieces on a monopoly board. They are used to a world where everything can be bought.

The entire system conspires toward this behavior. When our landlord of twenty years sold the building, we knew we couldn’t afford San Francisco market-rate rents. We started looking at the City’s down-payment assistance programs, took the required homebuyer courses, applied for the lottery, got prequalified for a loan paying 45% of our income in housing costs, got on realtor lists for homes similar to ours, two- or three-bedroom homes with a little space to make art and grow some plants. There were units that we could afford, in the Excelsior and Portola and Bayview, mostly near the freeways. The listings for the ones we could afford did not have fancy photos “staged” with expensive furniture and tastefully displayed off-the-shelf art and coffee-table books. If there were interior photos at all, they were photos of toys strewn on the floor, unwashed dishes in the sink, an unmade bed: the homes of a tenant family caught unawares by the intruding real estate agent. The choice was simple for us – we were not going to kick someone else out of their home because we were kicked out of our home. But the system is built for that.

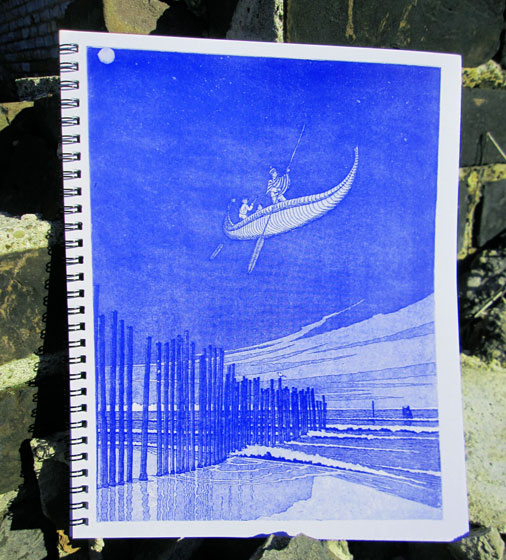

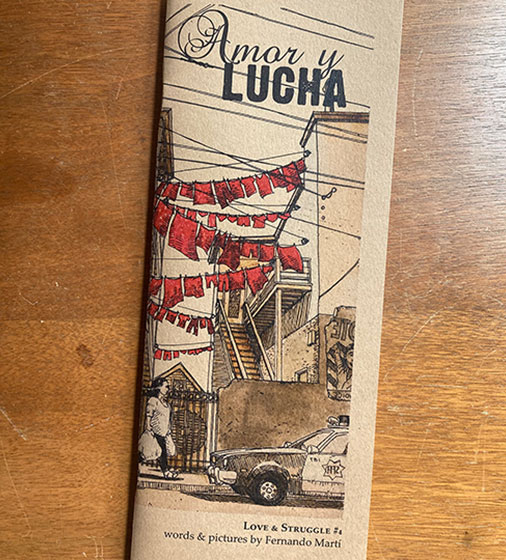

Much as this city has changed, San Francisco is still a sanctuary, it still provides opportunities for immigrants and refugees, for blue-collar workers and artists to build community and create culture. Working class people have been able to stay in San Francisco thanks to the militant history of tenant activism, who led the fights and passed rent stabilization laws (in SF, rents can only go up by 2-3% per year depending on inflation, until the tenant leaves), eviction protections, condo conversion limits, right to counsel. Thanks to rent stabilization I’ve been able to keep my three-quarter time nonprofit work, and be a parent and create artwork in the city I love. But the system pushes to extract as much it can from tenants, finding loopholes to evict people, push them out to the fringes of the region, transmute the city into a playground for the rich.

When I moved into my place twenty years ago, I paid the going “market-rate” rent for a two-bedroom unit. After living in my apartment for twenty years, always paying the rent on time, never bothering them, the landlords sold the building. My rents and the rent of the senior living upstairs paid off the owner’s mortgage (maybe several times over), and now in retirement they were cashing in on the San Francisco’s nouveau riche market.

Now the Omrans and their money are taking us to court. This process has been all-consuming, meeting with tenant counselors and lawyers, researching our options, organizing with our community, preparing for depositions. It’s no wonder tenants rarely take it this far. Who has the time, the resources, the energy, to keep going? There’s the fear, of deportation or harassment or how an eviction affects your future prospects, of losing your job. The rich count on that, the system is built on that. Going to trial takes over your life, your time, your mental space, your reserves. I’ve started waking at 3am, mulling over all the angles, or how I will get my work done.

We don’t have their millions, but we have community and we have what’s right on our side. We are tremendously lucky, that we are part of a community that has our backs. I can’t imagine doing this alone. Whatever happens, we will land on our feet, we will survive, even if it means losing our home and maybe losing our city and losing our schools. We will adapt. Many others are not so lucky – they end up in far-flung locations far from community and social networks, or in the worst of cases, end up on the streets, in tents or in cars or RVs, by no choice of their own.

We weigh our options, not alone, but with our community. As activists, as artists, we know how to organize, we are not uncomfortable going public about our situation. In all the focus on the fight, I hadn’t realized how wearing this has been: the outpouring of love and support from our friends and community at our press conference was a necessary energizing balm. A hundred people came, folks from Housing Rights Committee, CCDC, CPA, the Tenants Union, UESF, Causa Justa::Just Cause, PODER, member leaders from Faith in Action, and four city Supervisors. The story of our evicting landlords was picked up by the SF Chronicle and at least six other outlets. At our press conference, our friend Hillary Ronen, one of our city’s elected Supervisors, said, “We welcome you to this city. There’s room for you here. Just don’t come and evict people.”

As I write this, I’m sitting on my couch, observing the sign across the street, “for sale,” in the unit under Richard’s house. Why don’t they go for that unit? Three doors down, above the architects’ office, is the two-unit building that’s been empty for the twenty years I’ve been here. I hear the owner has finally decided to sell. Why don’t they go for that? We know there are ten to forty thousand vacant units in the city. Tatiana’s brothers own a property where two apartments were rented to a corporate rental company that we believe would have made a fine home for Tatiana. We joke with our twelve-year old about the empty apartment for sale across the street. Tatters could buy that unit, and then we could just walk across the street to hand her our rent.

People have choices, the Omrans have choices. They can harden their stance, choose to act as though our lives and livelihoods are simply calculations to be bought off. Or they can consider the ethical and social consequences of their actions, make connections across commonalities of colonialism and displacement, and choose to do the right thing.

It’s their choice.