Fire is part of the suite of factors on the short list for major contributions to human development. When we learned to control fire, we started using it to harden sticks for hunting, and eventually for cooking the food we caught. The flood of nutriment that we got from that food helped feed the development of these grotesque brains of ours, which must be seen as a dubious gift at this point. We used fire to do a lot of things as we spread out across the world, transforming landscapes into ones more suited to our needs, and driving a lot of species into the dustpan of history as we did it. One of the places where our fire practices had an impressively deep and even more impressively abiding impact was the island continent of Australia.

Australia’s always been a continent of fire. Many of the native tree species seem perversely engineered to attract and spread fire, throwing off long-smoldering strips of bark that float up on hot winds and start new fires miles away. When humans arrived, around 40 to 50,000 years ago, things changed. You can quibble over details, but there’s little doubt that humans changed Australia’s fire regime drastically. They moved across the continent in small bands, burning the country before them and causing major conflagrations. Those firestorms changed vegetation patterns in huge regions and helped to drive the extinction of some of the continent’s frankly bizarre former trove of massive, strange creatures. In the aftermath, however, humans did something pretty impressive. They adapted to the new framework they’d created and began to steward it with fire.

Humans learned to burn regularly and often. Their fires didn’t have much fuel to feed on, so they didn’t last long. The ash fertilized grasses, which brought out huntable game. Since people burned as they moved, fires threaded through the landscape in thready patterns, forming mosaic of burned and unburned habitat. In those unburned patches, the pig-footed bandicoot made its living.

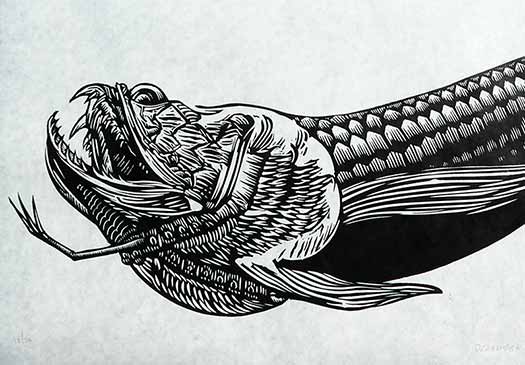

About a foot long, with a six inch tail, longish rabbity ears and a rear-facing pouch, the pig-footed bandicoot was a small and dainty animal with odd forefeet that resembled strikingly those of a pig. They inhabited the unburned parts of the fire mosaic, emerging to feed on the sweet green shoots of new grass in the burns. This arrangement served bandicoot and humans alike pretty favorably for a long time, until the unfortunate arrival of Europeans.

The Europeans put an end to Aboriginal fire practises in most of the continent. As a result, habitats were completely transformed, and food became scarce and unpredictable for the bandicoots. Unburned grass and brush built up over years and then burst into titanic holocausts that annihilated forests and shrublands, much in the same way that Southeastern Australia has burned in recent years. The bandicoots and the humans were pressed from all sides by the ignorance of the settlers and their fear of fire, which ironically only made fires ever so very much worse.

The humans made it, and Aboriginal fire practice has made some inroads into wildlands management in Australia, particularly in the Aboriginal lands of the north.

The bandicoot, however, joined the giant wombat, the giant short-faced kangaroo, and the marsupial tapir in the billowing clouds.