Read an article from the latest issue of Race, Poverty and the Enviroment that I was interviewed for. My homie Desi is also featured. His words are powerful! I shared my thoughts on the murder of Oscar Grant, the poster Jesus and I made in response and police brutality and state violence in general. See more about the project here.

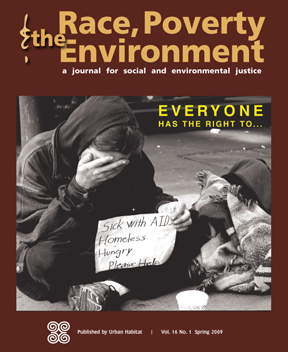

Race, Poverty and the Environment is a magazine published by Urban Habitat that features news, views and analysis for social and environmental justice. Inkworks has the honor of printing each issue and recently teamed up with the magazine to release a special poster in honor of Oscar Grant III and the Memorial Arts Project launched by the magazine (see below). The poster will be distributed along with the Spring 2009 issue which is focused on the theme “Everyone has the Right to….” It takes a look at the kind of organizing needed to win social and economic rights for all. Below is a short description of this theme as well as an excerpt from the magazine about the Oscar Grant Memorial Arts Project.

About this Issue:

As the current recession deepens, fundamental rights to housing, employment, healthcare, and safety continue to retract. As usual, low-income people and communities of color bear the brunt of the economic crisis. Foreclosure and unemployment rates in African American communities are double the national averages. The tragic murder of Oscar Grant on New Year’s Day by an Oakland transit police officer is emblematic of how even straightforward civil rights to life and liberty are in daily jeopardy.

While civil rights organizing has a long and successful history in winning social justice in the United States, a broader human rights framework—which includes the rights to housing, employment, healthcare, and safe communities—has less often been central to building mass movements. In this issue you will find a roundtable discussion on rights, in which participants discuss ways in which this platform is being brought into existence in organizing campaigns in cities and counties across the country.

As David Harvey says in an interview with Amy Goodman (published in this issue), the Right to the City Alliance and parallel campaigns across the world are raising questions about democratic control of public resources and even private priorities. Capitalism has always depended on state intervention to reconfigure itself following the inevitable financial collapses brought on by monopolies and speculation. But workers have also sometimes succeeded in using these crises to meet their own needs. Despite the fact that the Obama administration refused to attend the recent United Nations conference on racism and has taken reparations for African-American slavery off the table, grassroots agitation for redistributive justice is on the rise.

The silver lining in the current catastrophe is that ever more people—including many who previously refused to consider alternatives to capitalism—are coming to understand that the existing system is fundamentally flawed, and broad based coalitions for structural change are becoming a reality.

urbanhabitat.org/rpe

For links to past issues see below.

The Art of Protest

The Oscar Grant Memorial Arts Project

“The role of the revolutionary artist is to make revolution irresistible.”

—Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and activist

People are angry. Sometime after the midnight hour, a 22-year-old black man was murdered on New Year’s Day—another innocent victim of police brutality. His name was Oscar Grant, shot and killed in Oakland, California by a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) agency policy officer. Onlookers video-phoned the horrific spectacle: Grant surrounded by officers, unarmed, bleeding to death on the station platform, his arms shackled behind his back, his face pressed against the cement.

Several hours later, Laron Blankenship, a friend of the deceased, locked himself in a sound studio. He flashed back to the words Grant had spoken to him one day, “No matter what happens, even if I was to die, don’t quit doing this music thing.” His hands trembling, crying and near broken down, Blankenship produced a compelling rap anthem dedicated to Grant, “Never be Forgotten.” He sings, “I know for a fact your soul is still alive and you will never be forgotten.”

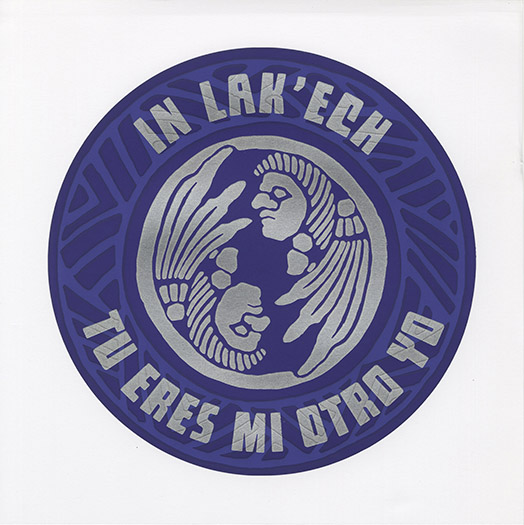

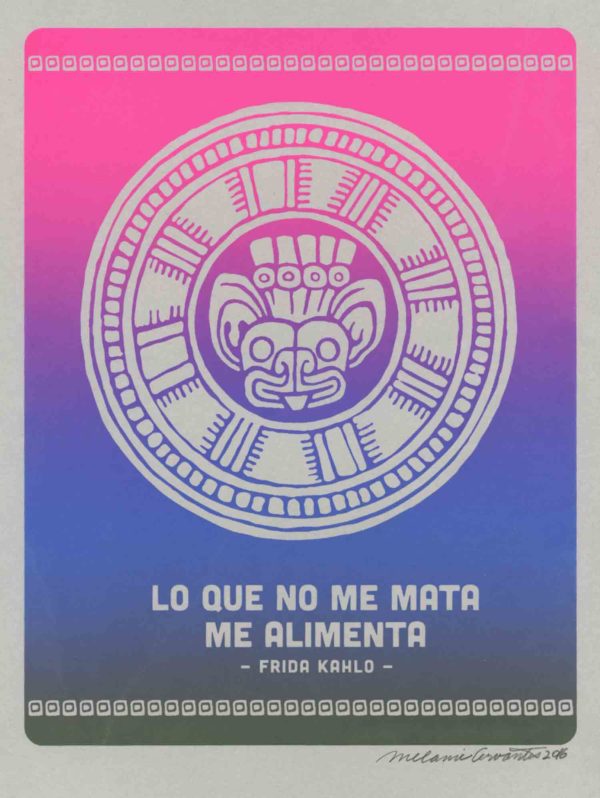

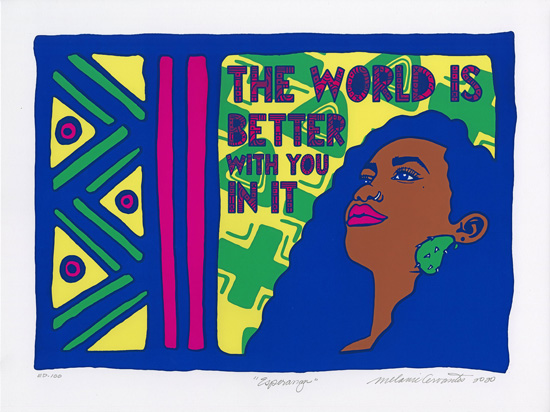

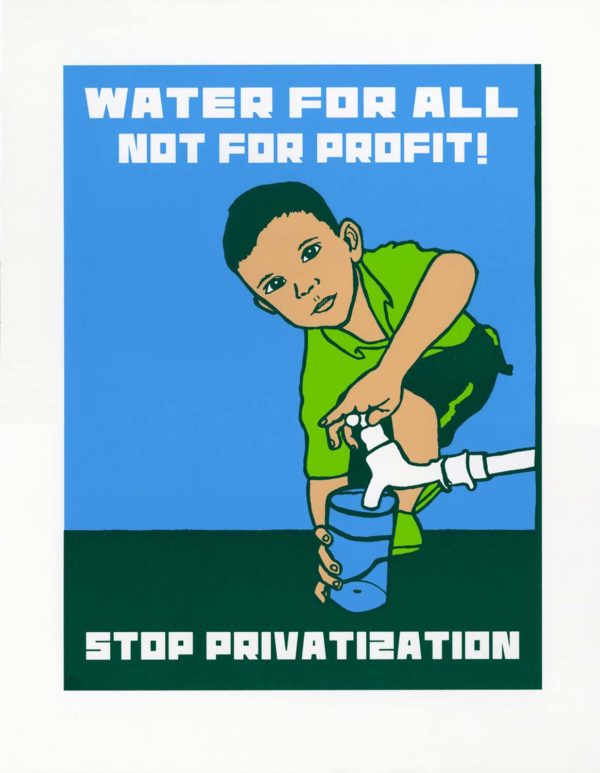

A few days later, artist and activist, Melanie Cervantes’ memories flooded back to the many instances of police brutality she witnessed growing up in Los Angeles. At five years old she watched the local library call security to kick her father out of the building. As a teenager, police victimized her peers on a regular basis. She says the video-taped beating of Rodney King and the later riots induced post-traumatic stress, which was re-triggered by Grant’s all too similar death. Spurred by these emotions, Cervantes and fellow artist Jesus Barraza created a visual call for justice that would resonate within the community and beyond. In a single evening, within the confines of their kitchen, they produced the first 50 silkscreen copies of their widely distributed poster bearing the slogan “Justice for Oscar Grant, Justice for Gaza, End Government Sponsored Murder in the Ghettos of Oakland and Palestine.”

One week later, during a protest demanding justice for Grant, a young Mexican woman’s voice singing in her ancestral Nahuatl language inspired graffiti artist Desi of Weapons of Mass Expression, while he painted the face of Grant in vibrant colors on the plywood sheets boarded over the windows of a 14th Street storefront. It read, “Rest in Power Oscar Grant” and “All Power to the People.”

Thousands have been appalled by the Oscar Grant shooting and have taken a stand to fight injustice. Many have chosen to creatively express their stance through the arts. Its forms have been many: Songs have been written and dedicated to Grant. Poems, paintings, and posters have been created. Graffiti artists have painted murals. These artists have contributed works to the Oscar Grant Memorial Arts Project, an online, print, and multimedia compilation of works dedicated to Grant’s memory.

Editor Jesse Clarke at Race, Poverty and the Environment says he co-sponsored the project because, “Art is an essential element in building the movements for social change. Oscar Grant’s murder is a catalytic event that crystallizes underlying social and political tensions.” Clarke says, “If his death is memorialized and communicated as a representation of those tensions, it can help build a movement. Similar tragic incidents which do not get codified can leave people feeling traumatized, disempowered, and more isolated.”

Movement Art

From the civil rights movement in the United States to the antiapartheid struggle in Africa and environmental activism internationally, art has been used as a symbol, to frame the message, to attract resources, to communicate information, and foster emotions.

“The strongest voice I have is my art,” says graphic artist Santos Shelton, another contributor to the memorial project. “Every day, people of color in this country are reminded that they don’t matter by the powers that be.” He says he made his piece entitled “Fighting for the Lost” because “Regardless of the fact that a president is black, the generations of hatred and social injustice that are still within society will take way longer to change.”

According to sociologist Jacqueline Adams, movement art helps communicate a coherent identity, mark membership, and cement commitment to the cause. It’s not only pervasive in many movements, it’s instrumental in the achievement of a movement’s objectives.1 Craig McGarvey, quoted in Art, Power, and Social Change agrees. He says art is a catalyst that makes change possible as it shapes the dreams, aspirations, and problems of people, thus inspiring them to work with activists/organizers to develop their collective authority and ability to build their community.2

“We dream it and then we manifest it into some form of reality and then it can actually happen. It’s an accessible way for people to identify with the issues and the movement. You can argue with protesters but not with the painting,” says muralist Desi.

Movement art is a crucial means of attracting people, pulling them together, and opening up their interconnectedness, McGarvey explains. Cultural change is made possible by the connecting influence of cultural exchange.

“Two summers ago, myself and a lot of other artists were working on an antialcoholism mural at the Raindeer Indian reservation in northern Cheyenne, Montana,” says Desi, reflecting on an experience where he witnessed people provoked to change by an artwork. “It was two to three stories tall, in the center of town, at an intersection. During the process, people were crying. Many came up to us, emotionally moved by the piece, promising to check themselves into Alcoholics Anonymous.”

A Catalyst for Social Change

From art emerges political and cultural resistance. We’ve seen it in the Civil Rights movement through the tradition of music in the African-American church, and in the farmworker rights movement through teatro in the fields. The birth of the hip-hop movement in the Bronx paved the way for a marginalized group of black and Latino youth to express themselves, communicate their experiences, and criticize social inequality and poverty. The use of photography by the Mothers of the Disappeared at Plaza de Mayo, in the context of post-dictatorship Argentina, reminds us of the state violence done to those denied the most basic human rights and the recognition of citizenship in a functioning democracy. 3

On behalf of mostly elderly Filipino and Chinese tenants who were fighting a battle against eviction at the International Hotel in the 1970s, artists protested alongside tenants and other advocates to become the cultural arm of the struggle by silk-screening protest posters, painting murals on the I Hotel, and producing exhibitions and publications. It wasn’t until hundreds of artists marched down Mission Street, with their faces painted white protesting the displacement of people of color in San Francisco, did the global mass media finally pay attention to the anti-gentrification message advocates had spent years trying to get across.4

Rooted beneath these acts of artistic liberation, produced by the soul’s inherent expressive nature, is the artist’s pain. Lives entrenched in poverty and hunger, a desperate need for healthcare, gender inequality, police brutality, institutionalized racism, and the myriad other evils of the system create deep wounds in the psyche. Creative visionaries recognize these injuries and their efforts are intrinsic to the healing process.

“The complexity of the racial reality comes down to the economy. Crimes happen because of poverty, which happens because of no jobs, yet millions of dollars are going into the police force,” says Cervantes. “I hope people see how various struggles are connected.”

“Police harassment is a symptom of the prison- industrial complex—it’s more valuable to put people into prison than to educate. It’s about trying to maintain power,” Desi argues.

The Struggle Continues

In 2009, in honor of Oscar Grant, artists are once again compelled to speak out using the greatest gift that they know how to use. They hope to spark change, fight corruption, and build stronger communities. Their designs not only critique the failures of the system that denies many of their human rights, but also pose solutions and open avenues to social health.

“The last time I spoke with Oscar Grant was the day he called me to wish me a happy birthday on December 3. I felt like getting back at the police officer. But instead, I wrote,” says Grant’s friend Blankenship. “I grabbed a dictionary to look up a couple of words to define the pain I felt—‘overwhelmed,’ ‘overexposed,’ and ‘despair,’—another innocent life gone. But my rhymes are not just for my situation. It’s for those that have lost someone dear and are feeling like life’s a wasteland.”

For poetry writer and activist Dee Allen, this was the best way she could pay homage to the memory of an African American working class man who was denied his right to a fair chance.

“Bay Area Rapid Transit’s management needs to know that the public will not forget this act of violence. No community—black, brown or white—needs young sacrificial lambs slaughtered because of some cop’s racist/classist power trip,” says Allen.

Brutality, never an “accident”

It’s systemic

And replicates itself

In different cities to the nth degree.

Bleeding

Stony hearts blame such handiwork

On “a few bad apples.”

And everyone knows

How that tired old maxim goes.

Tell that to the last

Victim inside the chalkline.

(Excerpt from Face Down by Dee Allen.)

Houston hip-hop artist Rukus chose to reach out specifically to Oscar Grant’s daughter. He wrote a song called “Dear Tatiana” like a letter, and dedicated it to her.

“We all know that this is unjust. People are gonna’ march. People are gonna’ protest. There’s gonna’ be a big court battle. Hopefully, this guy will end up going to prison,” says Rukus. “But at the end of the day when the dust is settled, when the last person has marched and put down their picket sign, there’s still gonna’ be a young girl that doesn’t have a father.”

Dear Tatiana,

Please don’t ask why does a man have to die

just to touch the sky.

I don’t have the heart to lie and say it’s alright when your daddy isn’t home tonight…

This is for father’s day, this is for single parent fathers who really give a damn and take care of their daughters. Ay.

This is the way I pray, wishing for a better day.

I’m staring at the picture of concrete where a brother lay.

(Lyrics from Dear Tatiana.)

The Power of Icon

The images created in memory of Oscar Grant, from the compelling figure with a halo and a spear, to the countless graffiti and poster prints of his face, bring to mind icons of past struggles.

One can see the resonance with “Handala,” the image created by Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali’s, which portrays a 10-year-old refugee boy with ragged clothes, bare feet, and his back to the audience—a symbol of Palestinian struggle and defiance.5

One can hear thousands of demonstrators marching through Mexico City chanting “Todos somos Marcos (We are all Marcos),” referring to the Zapatista Subcomandante who was being hunted by the Mexican government.

Oscar Grant’s memory lives on—encased in collective artistry, something that can’t be killed. Epitaph expressions painted on the side of buildings, gates, and even on mailboxes, echo the heart of the masses, “I am Oscar Grant.”

Endnotes

1. Adams, Jacqueline. “Art in Social Movements, Sociological Forum, Vol 17-1 (March 2002): 21.

2. David, Emmanuel A. and McCaughan, Edward J. “Editors’ Introduction: Art, Power, and Social Change.” Social Justice Vol. 33, No. 2 (2006): 1-4.

3. Ibid. page 3

4. Martinez,Maria X. “The Art of Social Justice.” Social Justice Vol. 34, No. 1 (2007): 1-4

5. Naji al-Ali remarked that “this being that I have invented will certainly not cease to exist after me, and perhaps it is no exaggeration to say that I will live on with him after my death.” www.najaialali.com