It wasn’t until I went back and watched all the films again later that I realized what makes them so interesting and compelling is not the hokey special effects (yeah, yeah, I know they were miles ahead of their time…) or Charlton Heston’s terrible acting, but the strange Hollywood channeling of white fear about Black Power.

Think about it, Planet of the Apes is a world run by violent, rage-filled, and seemingly irrational dark-skinned apes (clearly men in ape costumes), who have created a slave trade of (almost entirely) white humans, who are not simply silenced by their oppression, but ignorant, brutal, and literally mute, unable to speak! Apparently Black people in power leads to white people becoming completely stupid. I suppose in some ways that prediction has come true. Obama being elected—hardly Black Power!—has created an army of white nut jobs babbling incoherently about birth certificates.

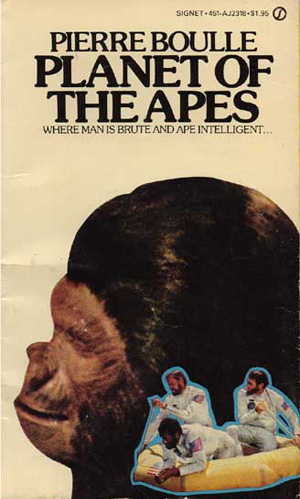

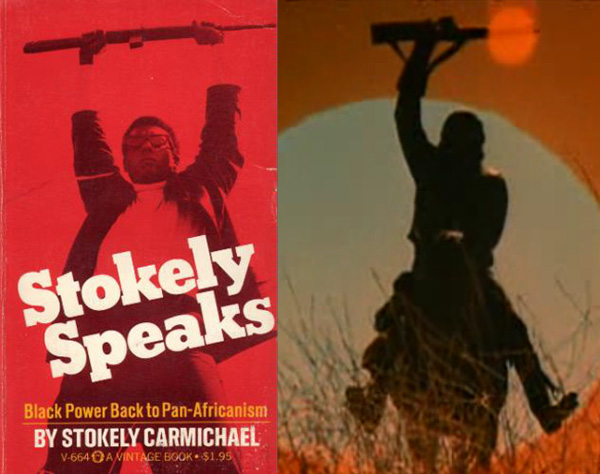

The new film, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, has some thrilling chase/fight scenes and impressive CGI, the acting isn’t terrible, and the plot is serviceable—in general I’d classify it as a mildly successful action film. But this isn’t supposed to be a generic action film, it’s supposed to be Planet of the Apes. Given that, the film seems to entirely miss the point. What was so powerful about the original Rise (titled Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, and released in 1972) was the fact that it was a combination slave revolt and prison riot in “apeface!” Conquest, and possibly even all the original films, would never have been made if the largely non-violent Civil Rights Movement hadn’t shifted towards Black Power in the late ’60s, national liberation struggles in the form of the Black Panthers and Brown Berets, and eventually by the early ’70s into small-scale guerilla warfare via the Black Liberation Army. Check out the similarities between the cover of Stokely Carmichael’s 1971 book Stokely Speaks, and the intro credits to the Planet of the Apes 1974 TV series:

The original Planet of the Apes film was an astounding channeling of the sublimated (and sometimes not so sublimated) white fears of what would happen in a world run by Black people. Conquest of the Planet of the Apes was a reenactment of the race riots that swept across the U.S. throughout the 60s, and a strange brew of both celebration and denouncement of the prison riots that were taking over headlines, especially the Attica Rebellion of the previous year. I can only assume that by the time Conquest was filmed, the producers understood that a large part of the appeal of the franchise was its visceral articulation of white fear (of Black Power, miscegenation, emasculation), so they pushed it up a notch, creating a U.S. where primates truly are slaves—servants to humans with no free will. The opening credits of the film run on top of large groups of men dressed as gorillas and chimps walking while standing up, wearing red and green jumpsuits (respectively), and being corralled and threatened by armed, uniformed guards.

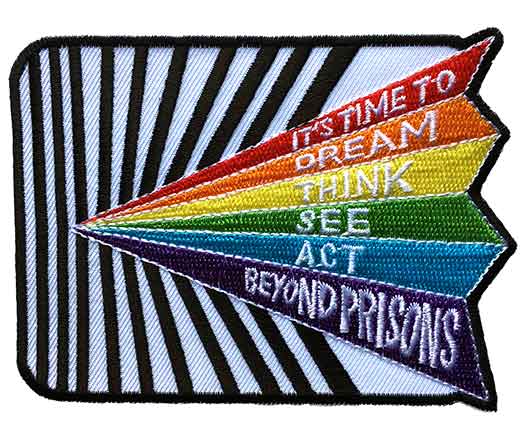

It is impossible to not read race, and the 1970s rise of the prison industry, into this. The rest of the film is an acting out of the apes coming to consciousness, rebellion, and eventual insurrection against their masters. Their revolt against the corporation that trains them to be good slaves is filmed just like a prison riot, and at one point a white guard actually bullwhips the black apes.

The larger revolt is certainly intended to evoke the urban riots of the ’60s in places like Detroit, Cleveland, and Watts. The apes are shown as intelligent and crafty, using advanced military planning to outwit the humans, as rioters often do (witness the past weeks’ revolt in the UK). If this wasn’t a clear enough indication for the audience that this film was about race (and full of references to the more political end of Blaxploitation films, like The Spook that Sat by the Door), the inclusion of a Black human character for whom the ape uprising causes both an identity crisis and an ethical dilemma—both terribly over-acted—throws the whole thing over the top.

The final insurrection/guerilla warfare scenes are potent not only because they echo the historical moment they were filmed, but they fulfill the promise of all revolutionary moments, that it is the oppressed that will liberate themselves. This is pop culture riffing off of Frantz Fanon, and it’s damn exciting. In a span of five short years Planet of the Apes went from a strangely racist science fiction thriller to an embodiment of Black Liberation.

The new Rise of the Planet of the Apes is anemic in comparison. After a single showdown with humanity (or at least with the San Francisco police force) the apes will rise, but not so much of their own doing. Their initial jump from simple chimps to an extremely intelligent column of primates is due to a human-developed virus tested on chimpanzees that smartens the apes, but also happens to kill off humans. In some ways this speaks to the contemporary fear of biology gone wild (a la dozens of zombie movies), but also sends some pretty confusing messages about the ethics of vs. the necessity of animal testing. (If this virus hadn’t been tested on primates, wouldn’t humans have just died anyway? Seems to me like an argument for more stringent testing protocols rather than animal rights.)

The race subtext has been completely, but only half-heartedly, replaced with this sub-plot of medical ethics, and the connected concern for animal welfare. One scene, where the main scientist/protagonist (played by James Franco) visits his bio-engineered chimp Ceasar in a poorly run and brutal primate facility, looks to be an almost shot for shot fictional remake of a similar scene in the recent documentary Project Nim. (In the above two images, the top one is from Rise, the bottom from Project Nim) We are made to feel for Ceasar and the other apes, but even with advanced CGI gorillas and baboons acting increasingly human, the animal rights narrative is no where near as compelling as the racial overlay in the original. While animal rights are becoming a larger narrative, they still pale in comparison to the reality of racial inequalities in our society. To call the eventual ape escape and victory against the humans in Rise a story about the ethics of animal treatment would be far-fetched. Such high morals are ill-fitting on 2011 CGI apes, just as they are on most actors in contemporary Hollywood movies.

But race is not entirely absent from Rise, it simply doesn’t seem to matter—on the surface at least. Franco’s character falls for and eventually partners with a South Asian veterinarian (who may also be the only female character in the film, if I recall correctly, and is played by Freida Pinto of Slumdog Millionaire fame), and his boss is a greedy, high-powered CEO who is both the main bad guy in the film, and also happens to be Black. So I suppose in forty years some things have changed, miscegenation with hot women of color is no longer taboo, but Black people in power is still the fastest way to the end of us all.

I was hoping, from the trailer, that The Earth rebelling against oppression would be a theme of the film — which is certainly an anxiety of the moment. That still would not necessarily be a superior narrative to the one you’ve outlined, but at least an interesting one. I will have to revisit the original series!

The original French novel “Planet of the Apes” by Pierre Bouelle was explicitly racist. He wrote it in 1963, after France’s African colonies had seceded en masse, the “apes” in his book were stand-ins for Black Africans and the theme was his fear that Blacks would take over Europe and ruin it.

The films, while cleansed of Bouelle’s in-your-face racism, tended to use the apes as allegories for Black people in America.

The current movie dispensed with all of that racial garbage. The apes here are APES and the main theme of the current film is how science and the drug companies use and abuse highly developed and sentient animals for profit.

I really liked the movie – far better than any of the original Planet of the Apes movies!

And, as it is now 2024, we can see that he was correct…

Interesting analysis. I’d always thought that the original Planet of the Apes film was about animal rights…a kind of role reversal to illustrate how humans would feel if they were the ones being oppressed instead of the other way around. And a warning against nuclear war of course. I’d always considered it quite progressive because of those things. Race genuinely hadn’t even arisen in my mind as a subtext. Looks like it definetely was in the sequels though, but I haven’t seen those so can’t comment.

NY times articles with a different perspective of

“different anxieties for different times”. It seems to miss all of the points Josh brings up.

“Apes from the future, hilding a mirror to today”

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/31/movies/a-new-film-in-the-planet-of-the-apes-line.html?pagewanted=all