I’ve just returned from a 6-week residency (along with my partner Erica Thomas) in Medellín, Colombia, as a guest of Casa Tres Patios; an arts organization affiliated with the University of Antioquia that connects artists whose work has a social or political component with communities in Medellín and the Antioquia department. During discussions prior to our arrival, the staff of C3P offered us the opportunity to work with some people from the FARC, the political organization that has been formed from the decommissioned forces of Colombia’s longest-running guerrilla army. This sounded interesting to both Erica and myself; a chance to connect with people deeply involved in the complex history of Colombia’s armed conflicts and to learn from and collaborate with them.

Within a week or so of our arrival in Medellin we had a meeting with Christina, a former FARC soldier who works now in the context of political communications for the new political entity that FARC has become. It can be slightly confusing to keep these entities separate, as they’ve kept the same acronym. Where once was a 20,000 strong military organization called the Fuerzas Aramadas Revolucionarias de Colombia that fought a Marxist-Leninist armed struggle against the Colombian state for more than fifty years, now exists a smaller organization that has handed in all of its weapons, decommissioned its forest bases and cocaine labs, and transformed itself into a political party known as the Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Comun.

We asked Christina where she thought might be a point of entry for a couple of North American artists. I work mostly in printmaking and murals and Erica works in social practice. She noted that there was an upcoming gathering of FARC organizers outside of town and that we’d be welcome to attend. We talked about political communications and screenprinting, and possibilities for a workshop.

The gathering was to take place in one of Colombia’s ETCR’s (Espacios Territoriales de Capacitacion y Reconciliacion or Territorial Spaces for Training and Reconciliation), the rural encampments that the government built to house former soldiers as they emerged from their lives of clandestine armed struggle. These spaces were built across the regions where the FARC held power, and are currently housing about 5300 ex-combatants. The meeting that we were scheduled to attend was a chance for regional organizers to get together and share ideas and methods, as well as to learn more about what being part of a political party meant after many years of operating under military authority. FARC’s structure as an army had been less rigidly centralized than other guerrilla forces, but the arrival of a formal peace meant that the responsibilities people had to the movement were suddenly different. We were interested to find out how different, and how people felt about the new work they were doing.

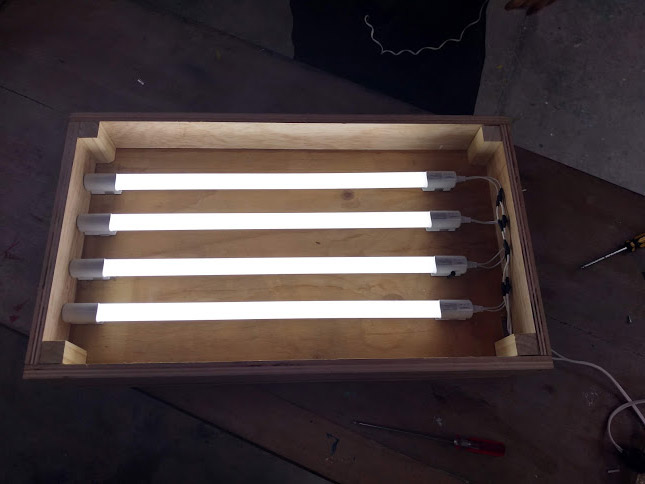

First, however, the practicalities. We met with the other residents at C3P (Amelie and Suzanne from France) about what we should work on, and came up with a plan for a workshop that included online communications, video, photo, graphics, and screen-printing. The plan was that we would start with long-form communications, and distill those down to frames, then to sentences, then graphics with slogans, and then burn some screens and print. Alvaro (a Medellin-based artist and activist) and Victoria (the curator at C3P) and I visited a few shops in Medellin’s central commercial district (an area known as the Hueco, or Hole) to find basic silkscreen gear as well as the materials for building a light table. A few LED tube lights, a piece of glass, some wire, and some wood-scraps. We nailed it together, taped the wires, plugged it in and test-exposed an image, and it worked. I made a lid for it so it would survive the trip.

We took hire-cars before dawn out of the city into the rural landscapes to the northwest. Antioquia is one of the most thoroughly rumpled landscapes imaginable, all green slopes rucked up into dense wrinkles and impossible to punch a highway through. It took us about five hours to travel the crow-flies hundred miles to Segovia, where we transferred out of the cars to a beautifully decorated country bus, a durable beast loaded down with sacks of goods and travelers headed further afield. Rumbling out of Segovia down an increasingly rutted and stony road, we followed the course of a river that had been utterly destroyed by placer mining for gold, and indeed the process was still underway- backhoes stood in the caramel-colored watercourse dredging gravel onto conveyors for people to wash with mercury and cyanide in hopes of recovering faint flecks of yellow metal. The riverbanks were churned masses of loose rock, poisoned beyond recovery, for miles.

The further we traveled, the greener the landscape became, interspersed with zones of blackening where forested slopes had been torched to clear ground for cows and crops. Fragments of intact forest lined ridge tops and wound through the gnawed fields, dotted with small and neat houses and fenced enclosures for pigs and horses. After a few torturous and tooth-jarring hours of steep and ragged road we passed through the village of Carrizal, a dense cluster of wooden buildings built close by the road, and just beyond its edges Victoria signaled to the driver to stop and we piled out in a cloud of red dust. This was the end of the line. We unloaded and hauled off our gear, all stained a comical orange by the leagues of dust. Uphill into the compound lined with acrylic murals of toucans, macaws, spectacled bears, and the new FARC logo- a democratic socialist rose symbol, painted across the central office next to a big stencil of Che.

Christina met us and found us a room in the hardboard structures that made up the barracks. The whole camp, consisting of about 12 buildings with 10 rooms each set on a big concrete pad cut through with rain gutters, sat on a hill overlooking a network of valleys, small pineapple plantations stretching up to the treeline of uncut forest. A central kitchen and mess hall, some small and large meeting rooms and a large square.

We found some empty metal cabinets and rigged them up to dry coated screens in, propping a fan against the doors and draping blankets over the openings. We went over to the camp bar and had a beer as the sky burnt up at dusk. That night a movie was showing in the meeting hall, prefaced by a long lecture from a man in a red shirt describing the crucial moment in Colombia’s history that the movie addressed, the assassination of Gaitan in 1948. Gaitan was a politician who emerged from a liberal tradition to flirt with nationalism and populism in a peculiarly Colombian mode, turning political attention for the first time onto the poor rural population of the country and building power among the peasantry to the great terror and disgust of the landed gentry, for whom little had changed since independence from Spain. Gaitan’s assassination by a disputed actor of uncertain motive precipitated what is known as the Violence, a long period of conflict, mass murder and civil fragmentation that gave birth to the numerous armed factions that fought the state and the right throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. That’s where the FARC was born as well.

The next morning we met with the crew of people who were participating in the workshop. All under thirty, they were the designated representatives of communication teams from ETCRs across Antioquia, here to federate and to connect and figure out how better to do the job of political communication and messaging in the incredibly remote and rural locations where they were based. We started off by having them list their concerns and desires, what they thought was important to communicate, and what they wanted out of the workshop as a whole, what problems they faced regarding communications where they were, what they imagined going forward.

Over the next couple of days we worked through those ideas and concerns. Preeminent among them was the fact that in the peace context, after handing in their weapons, the ex combatants of FARC are being slaughtered in inordinate numbers by the paramilitary forces they had been fighting for so long. The right wing paramilitary factions in Colombia have been responsible for something like 80% of the killings and kidnappings over the last forty years of conflict, but share equal or lesser billing in public consciousness as culpable parties for the violence- this is largely due to tight alliances between factions in the ostensibly legitimate government and the paramilitaries. The people we were working with were deeply concerned with correcting the record about FARC culpability in massacres, murders, disappearances, rapes, kidnappings, and generalized political violence, against the tide of misinformation and bad faith the internet disgorges.

We hung paper on the walls and listed the concerns and problems they had with their roles as communicators in isolated rural Colombia: bad internet, slow transfer of information from a central policy source, lack of resources, lack of money, threats of violence. There was a lot of earnest desire to fulfill the promise of disarmament and the transition to purely discursive political action, but a lot of frustration with the means available.

We went to the cafeteria for lunch, and wandered around the compound afterward. Erica went up the road to take photos and received an impromptu tour of the camp’s agricultural efforts from a man and his young son. Pineapples and peanuts in the red soil on steep slopes, and tilapia in the muddy ponds at the bottom. The hillsides were freshly charred to expose new soil.

We reconvened after eating and started off having the participants pick themes from the ones they’d listed and pair up to make short videos about those themes. Amelie and Erica described some methods of composition and framing, and teams fanned out across the barracks to film each other in front of the murals or standing at the hillside with the crops visible below. Regrouping, we watched the shorts and critiqued them. Then we did the process again but as a single still image. Teams composed and shot the images and composed texts to accompany them.

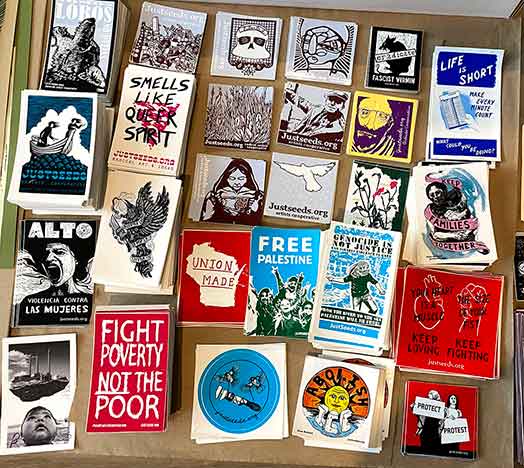

I gave a little slideshow of political graphics through the ages, showing some from Paris in ’68, some from Quebec in 2016, Sandino’s hat, masked Zapatistas, the famous image of Che, to inspire ideas for the creation of simple images for screenprinting.

The sun was setting fast when we stopped after the end of this second round. In the central cafeteria the heavy plank tables and benches were full of people tucking into plates of rice and plantain and meat. After dinner there was a gathering in the main meeting hall where everyone in attendance lined up on benches to hear each other speak. Everyone who got up to address the room cited their years in combat after giving their names, their areas, their commitments. 20 years, 5 years, 13 years, 35 years. The main event was an address from a man wearing a Bob Marley t-shirt, and he spoke at length about the situation that the FARC found itself in and the prospects for the future. Violence and the refusal of violence, machismo and male identity in the absence of the gun, the power of women in the organization, and the economic projects that the central leadership was hoping to use to keep the movement going. The young people sitting if front of us looked very much like soldiers in civilian clothes, and they nudged each other to stop playing on their phones and listen.

I got up before dawn to walk out into the forest. The road south was silent and quickly entered thick primary forest. Toucans skronked in the high canopy, and kiskadees hawked among the carmine sprays of treeflowers thirty feet up. Big mysterious birds hopped through the shadows on big branches and I saw them through binoculars as weird sillhouettes and backlit purple combs and chocolate tailfeathers. Big trees straddled the roadside, split and twisted and worthless as timber, draped with vine and liana.

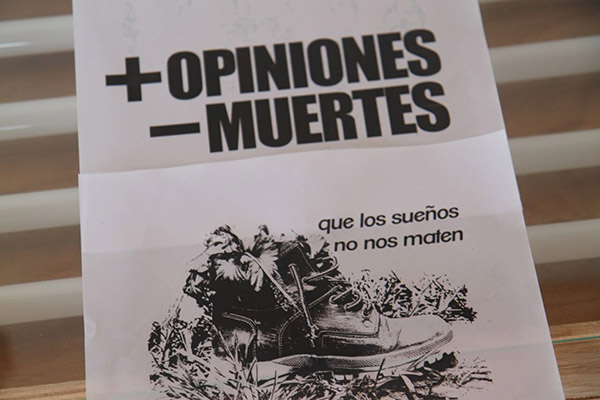

Back at camp we started to condense the messaging further, selecting a couple of the images that people felt best described the ideas they wanted to communicate and working on slogans to accompany them. Ideas went up on the brown paper taped to the wall, ideas were scratched out. Images were looked at again and others were chosen. We settled on three.

Over the next hour or so we played with those images on computers and in image editing programs in phones, working on high contrast images that read well, adding text in different ways, changing the text, mixing everything around until it seemed like it was going to do the job that was desired. Erica fixed the laser printer that Christina had in her room and we printed films, greasing them up with oil borrowed from the kitchen, wiping them down and setting them up for exposure on the light table.

The exposures worked, but we ran into a problem that I’ve had before trying to set up a screenprint project in zones with little infrastructure: lack of water pressure. All the water was coming from rooftop tanks and the pressure wasn’t strong enough to get a good stream for washing out the screens after exposure. With some careful swabbing and scrubbing we managed to get two of the images onto screens.

After lunch we printed. We printed patches, shirts, hats, we experimented with rainbow rolls, we printed onto the walls of the room we were using. We used up all of the fabric we brought and rested in the late heat of the afternoon to the sound of the small parrots flocking in the trees outside.

Christina came over to tell us that a ride was leaving if we wanted a quick route back to Medellin. We said goodbye to the team and packed up our gear, loading it into one of the numerous Toyota SUVs that littered the parking lot, each identical to the others except for the novel security doors that a few of them had within their outer doors, like nictitating membranes in the eye of a lizard. Some of the people who had spoken at the meeting piled into one of the advance cars, and we loaded our gear and ourselves into the second and third. Dogs trotted after us as we peeled out and down through the dust. It felt suddenly very much like a military convoy, and I flashed to the story that the man in the red shirt had told us about the recent killing of an ex combatant in a town about thirty miles away, whose body had been hauled to Carrizal in the dead of night and left in the office in the height at the center of the camp. 130 ex-combatants had been killed in the last few months, many by motorcycle assassins pulling up to their cars stopped at lights or obstacles. We pulled over as we passed through Carrizal, dust clouds billowing past us and into the empty bars at roadside, coating the already obscured pool tables and their plastic covers. One of the ex-soldiers from the first car leapt out and ran into the open face of a building at the end of the commercial strip. Goats trotted past on the right. The soldier emerged with both hands full of ice-cream cones, and went from car to car offering them in through the windows. We accepted, and then the windows went back up and we rolled off down the hill into what was left of the forest.