Last Friday, Yolanda López passed away.

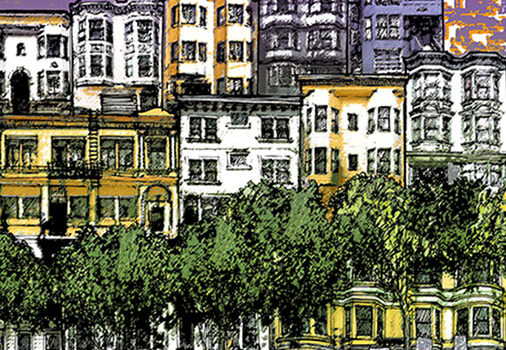

As I put my head on her body, I felt other ancestors in her presence, my own mother and father with whom I wasn’t able to share their transitions. I hoped she might give them a good report. To me, Yolanda was that thread of history to this place that I have come to call home, San Francisco’s Mission District, and that connection from this place to all we could aspire to as a people, as Raza, as artists.

From Los Siete to today

In the late 90s and early 2000s, as a young architect/artist in the community, I found my way into the Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition, MAC. Eric Quezada taught us about that legacy of Yolanda Lopez and Donna Amador and Los Siete, that political conscience we so desperately needed, caught up in the nonprofit industrial complex: Third World Internationalism, feminism, the role of culture in our organizing.

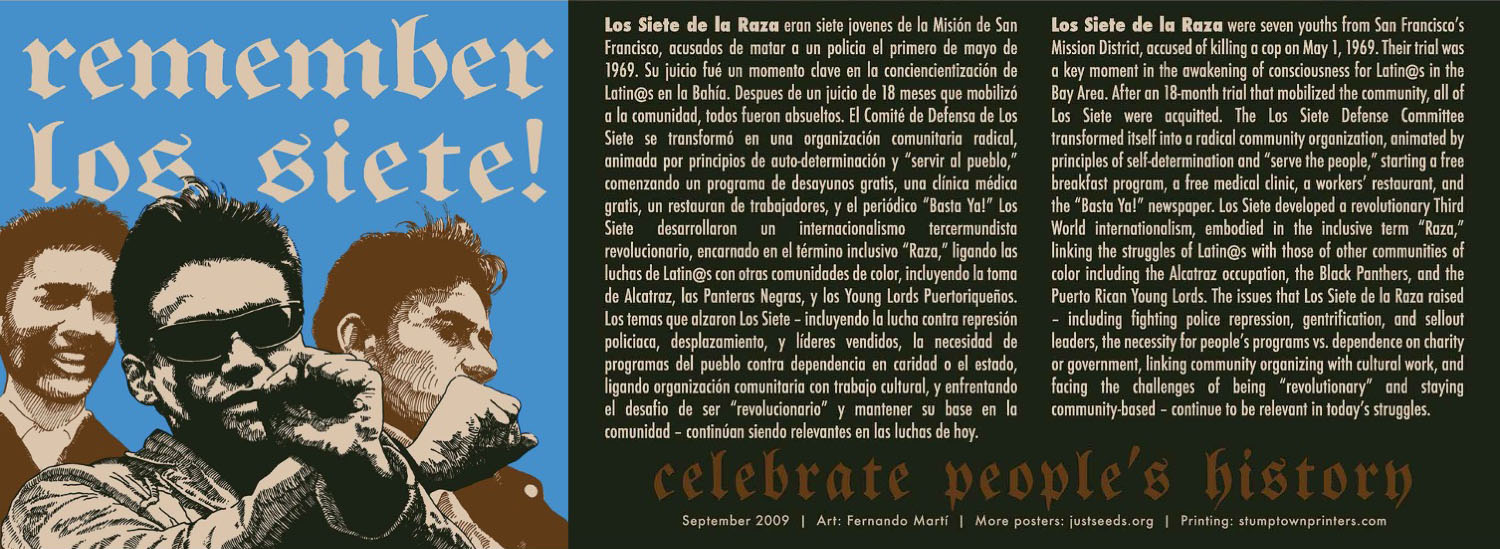

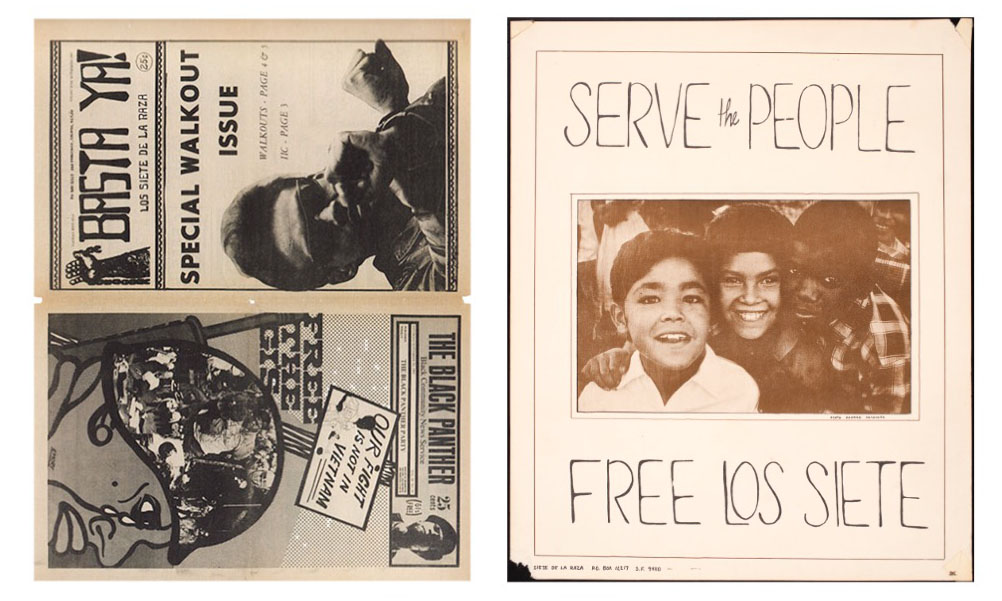

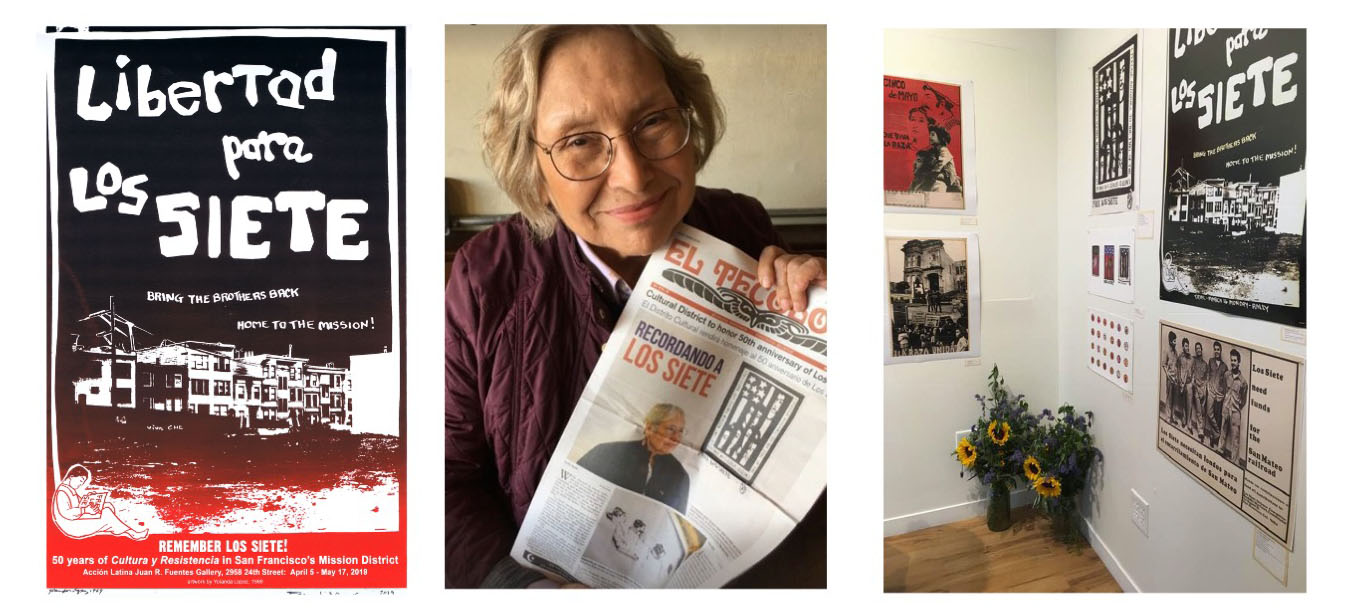

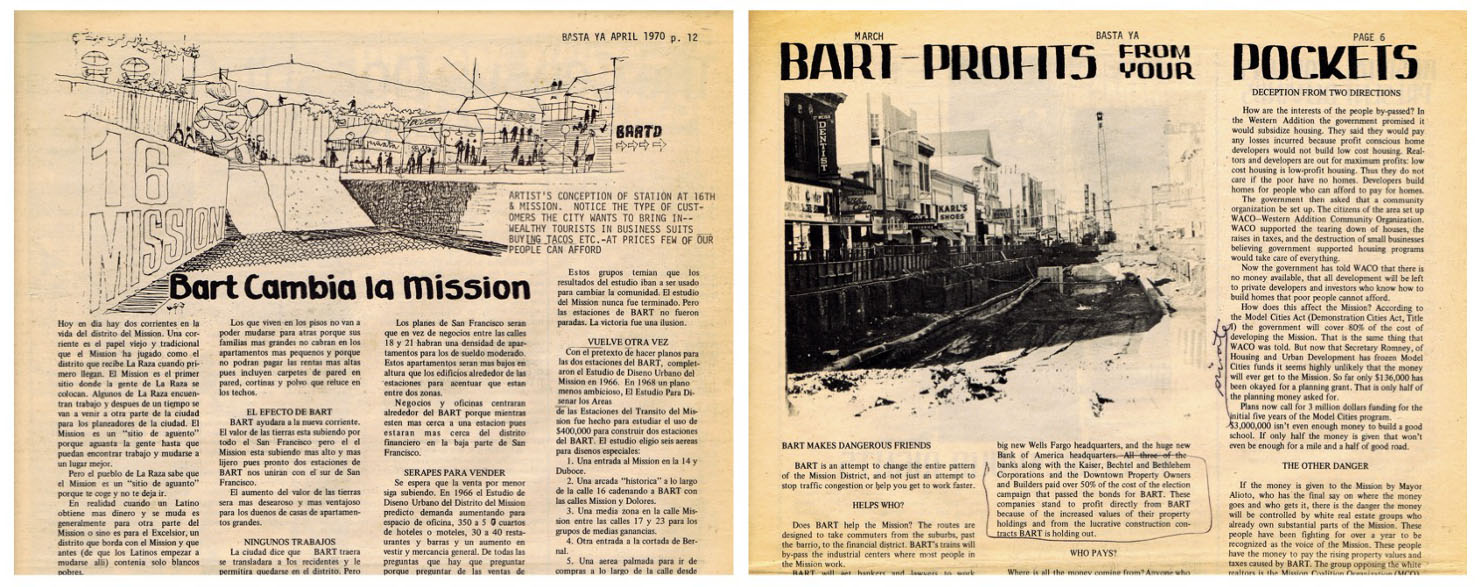

Fifty years ago, in 1969, seven young men in the Mission were accused of killing a police officer, while the cops ran wild in the barrio, rounding up young men. Yolanda, fresh from SF State’s Third World Strike, threw herself into the responsibility of taking those things she learned in college – academic skills, technical skills, organizing skills – back to the community. Yolanda brought her artistry and creativity and energy and political questions to La Lucha, to the Los Siete de la Raza Defense Committee, to turn that struggle into programs to Serve the People: a community newspaper, a free breakfast program, a free clinic, and a workers’ café.

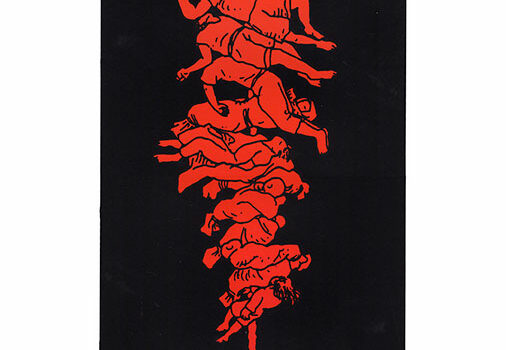

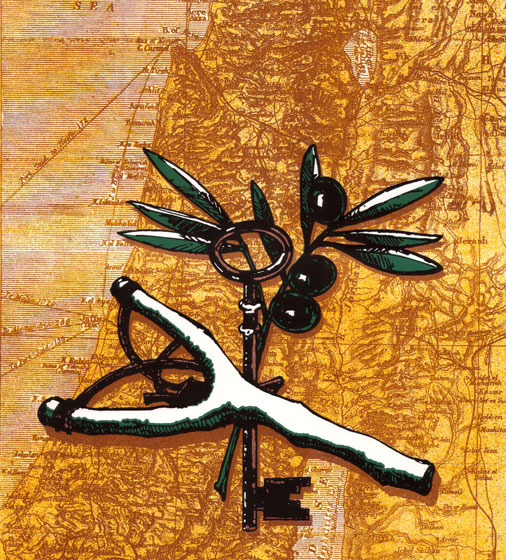

Through Los Siete’s newspaper, the Basta Ya!, Yolanda developed a visual language of Raza revolt that reverberates still in the Mission and throughout Aztlan, that echoes through 50 years of Mission District resistance and construction.

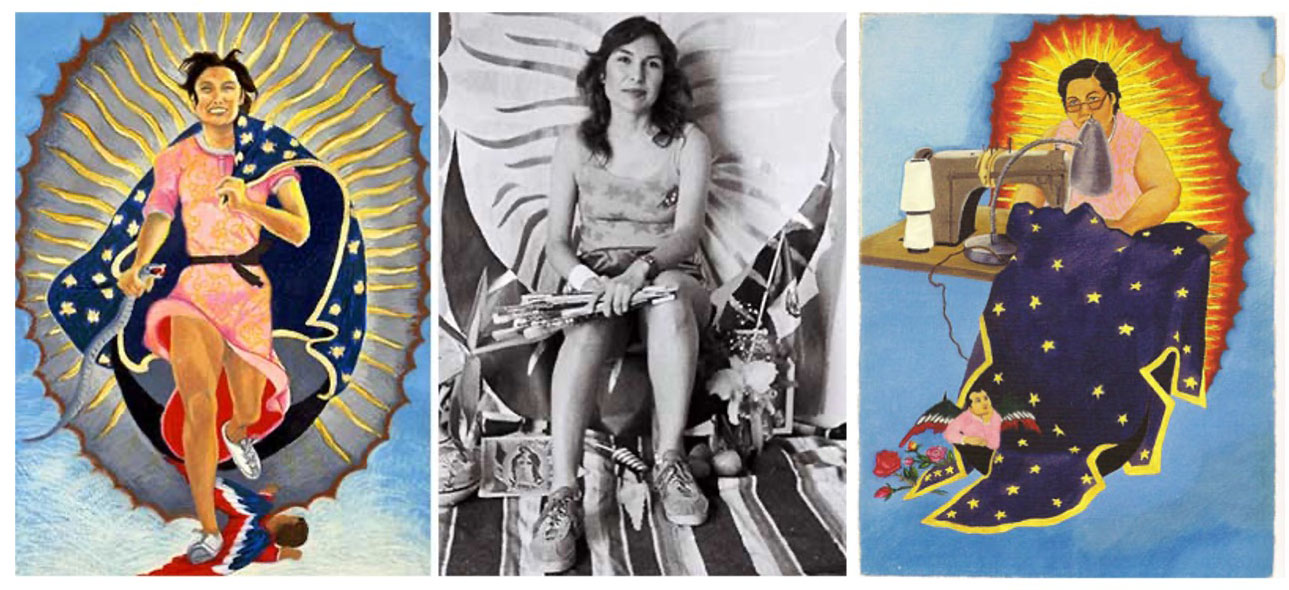

At the beginning of the 20-year war in Afghanistan that only finally ended this week, Betita Martinez, another great who passed away this year, took a few of us under her wing to organize a Latin@s Contra La Guerra. Yolanda Lopez was there, umbrella in hand to protect herself from the sun, with the most beautiful protest banner I had seen in my few years of protest and arrest, a hand-painted canvas with roses and vines snaking around our statement against the war. Yolanda encouraged us to bring our beauty to our anger. She reminded us that it was our job as cultural workers to reclaim our traditions, nuestra Virgen de Guadalupe and Tonantzin and Coatlicue, looking to the past to remake our culture for the future. And to bring our lives into that cosmological vision: La Virgen as Yolanda’s mother seamstress, reminding me of my own aunt who raised me in San Gabriel, working as a seamstress.

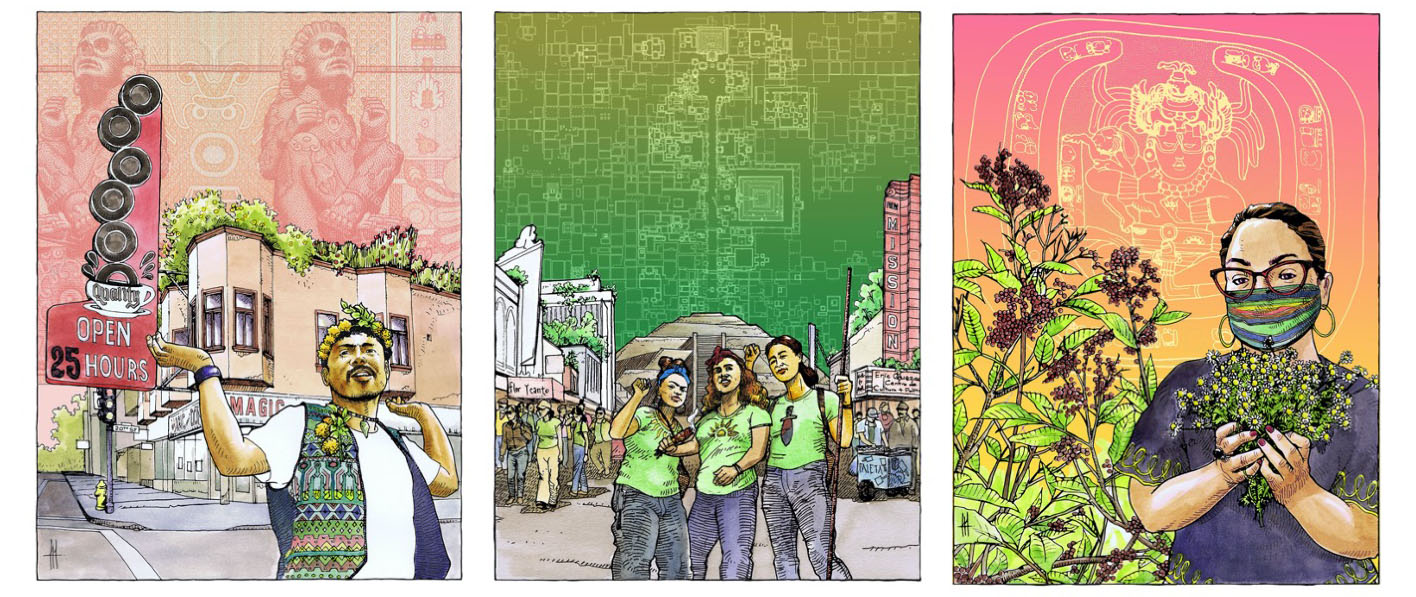

Yolanda opened my eyes to the permeability of culture, not as a fixed thing but as a living, evolving, critical part of our lives as Raza. As with her art, she spoke of politics not in terms of limitations, of what was safe, but of not holding back, of pushing the limits of what was possible. Make a ruckus! I think the possibilities she opened up in the 1970s echo in my own search for a visual language to meld ancestral knowledge with a Futurismo we can call our own.

Yolanda shared with us the lessons of Los Siete: as some burned out or moved on with revolutionary fervor to organize in the factories, the women stayed in the community, as teachers and as artists, still organizing, for the long struggle of building up new generations and creating new culture. Yolanda was a true organic intellectual, an artist of the people – mentoring one after another of us. She is only next month getting the retrospective she deserves, at the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, but for so so many of us, she is the chingona elder we needed right here. Her importance rippled in the generations of artists she encouraged – and then those generations, like Galería de la Raza’s Ani Rivera – in turn are nurturing the next generations of Latinx artists, questioning and queering and evolving our mestizajes into new cultures.

The Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition tried to meld the institutional capacity that came out of the old MCO with the radical politics and culture that came out of Los Siete. We developed a People’s Plan for the neighborhood, identified sites for gardens and parks and housing for the community, and fought the speculators lot by lot. We began to think of community self-determination in terms of the tools we would need to preserve the housing our folks already had, before the whole neighborhood was lost to speculators. At the Council of Community Housing Organizations, where I’ve been co-director for the last 10 years, we fought for the funding and then programming and then a whole legal framework to buy up apartment buildings off the speculative market and into community ownership, to make that vision into reality.

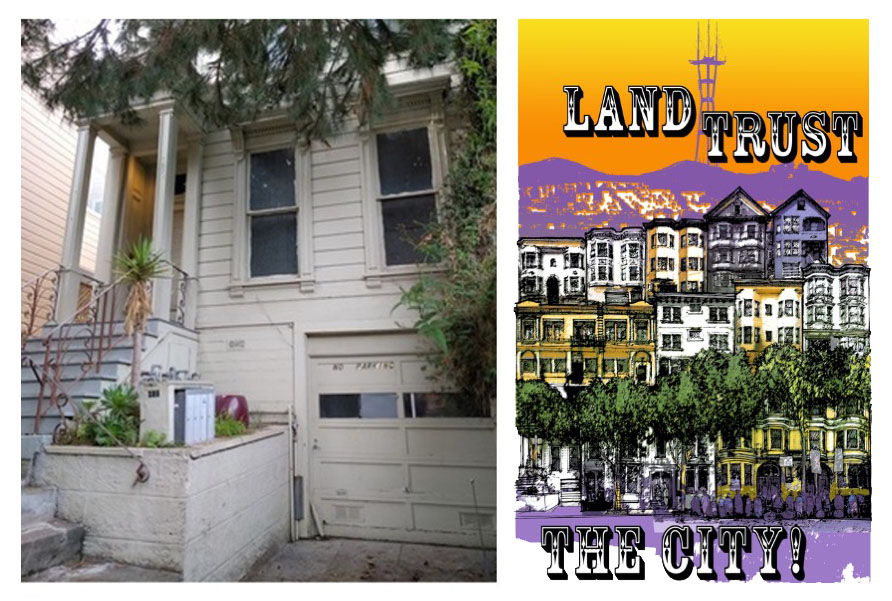

The forces of the market that Los Siete fought against continue to use the barrios as colonized spaces, seeing us as mere pieces on a Monopoly Board, handing over our paychecks as rent, and then disposing of us whenever they want. When Yolanda Lopez’s home was bought by one of the most notorious serial evictors in the City, one of the first victories of the program was to preserve the home where she and Rene Yañez had lived for decades as permanent affordable housing.

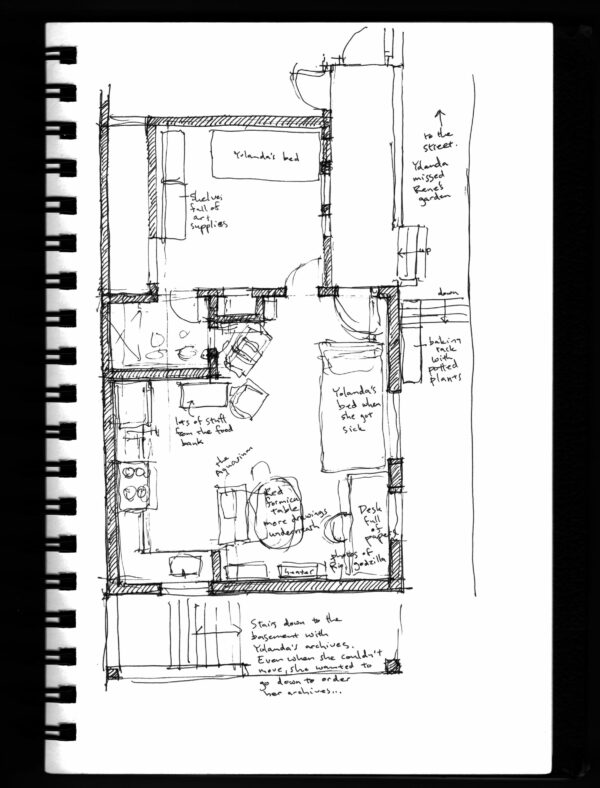

Visiting Yolanda over the last few years, it was clear that home was so much more: Rene’s garden at the front, the corner with her desk and pictures of Rio and a giant Godzilla doll, piles of artwork hiding under the red formica table, shelves of art supplies, her archives in the basement.

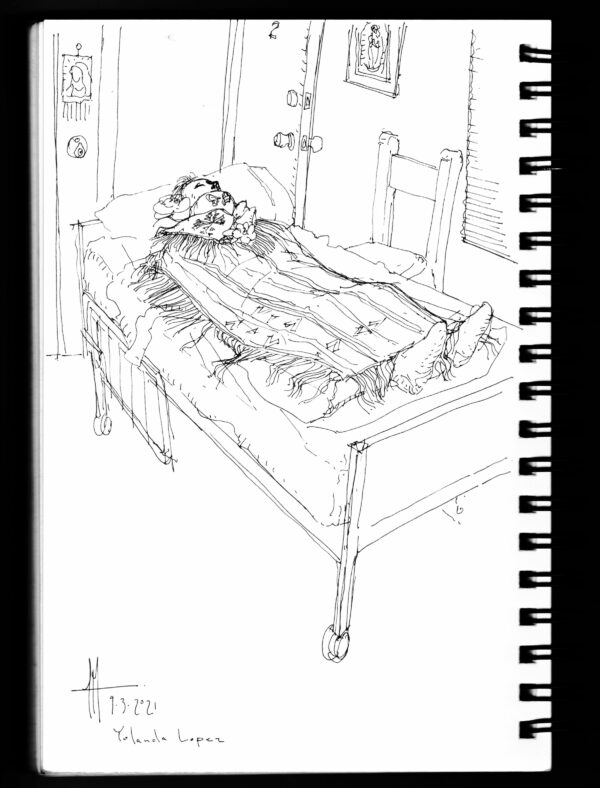

When she chose to not go on with cancer treatment this year, she and her son Rio called on a group of her chosen family to gather and comfort Yolanda and help her in her transition. It was a last gift that Yolanda gave us, the chance to be with her in community these last few weeks. Yolanda transitioned in that same home our little housing program had saved: the place that centered her body, her family, and her chosen community. Home is not just the place to sleep and cook dinner, not just the place it has become for distance learning or working from home or isolating during the pandemic, but sometimes the place that marks the transitions of our lives: the first moments of the birth of a child, or the place that holds us, with our family and friends, in our last moments.

On Friday, we gathered to say our goodbyes, to dress her and pray with her and send her off with tobacco and semillas de maíz, to light an altar with her favorite Fritos in soup and arroz con leche to help her on her journey.

Self-determination in the Barrio

The internal community contradictions that Los Siete de la Raza had exposed in the 70s continued to echo in the 2000s, as the affordable housing organization I worked for in the Mission imploded. Yolanda minced no words about those she remembered as snakes and sellouts. The community continued to bleed, fighting for community spaces and housing in the face of individual evictions and wholesale displacement. With MAC and PODER, we staged sit-ins and community celebrations and danzas at a parking lot on 17th & Folsom, led design workshops and envisioned a park and homes for the community rising there. We cornered the Planning Department, and the PUC who owned the land, and Parks & Rec, and the Mayor’s Office of Housing, and little by little the pieces fell into place, every one a struggle. After almost two decades with no new community-based housing in the Mission, there are now six new buildings completed or almost completed. Each one was a struggle that echoed the struggles that the Basta Ya! chronicled: whether stopping the PUC or the School District from selling off their underutilized sites, or wresting pieces from the big land developers or chain stores. All along, those fights were happening at multiple levels: whether in the culture of resistance, in the block by block fights, in developing new development capacity in the community, or the fights the coalition I work for, the Council of Community Housing Organizations, led for the needed funding to make these projects a reality.

In 2019, I curated a 50th anniversary exhibit of Los Siete with Yolanda at El Tecolote. One begins by thinking of an exhibit as a space with art on the walls and ephemera in cabinets, but it’s really about a container for deepening or creating relationships: connections to the veteranos of Los Siete, to old Black Panthers, to PODER’s young people, to those fighting for the memory of Alejandro Nieto and all those still targeted and murdered by police in the barrio, to the activists of Plaza 16. We brought the elders together, led bike tours with young people to the sites of the Serve the People programs: the breakfast program, the free clinic, the worker’s café.

Yolanda insisted on hand-cutting the names for each of the seven young men, and as we worked all day at El Tecolote’s storefront, community came in, sat down with Yolanda, took part in the process of remembering and recreating culture.

Los Siete was a small part of an incredible organizing moment in the Mission District that fought off urban renewal plans that would have destroyed the neighborhood for blocks around each of the new BART stations. But after the fight was won and the organizations went on to build up new institutions, Los Siete continued to see the underlying economic forces around the BART stations.

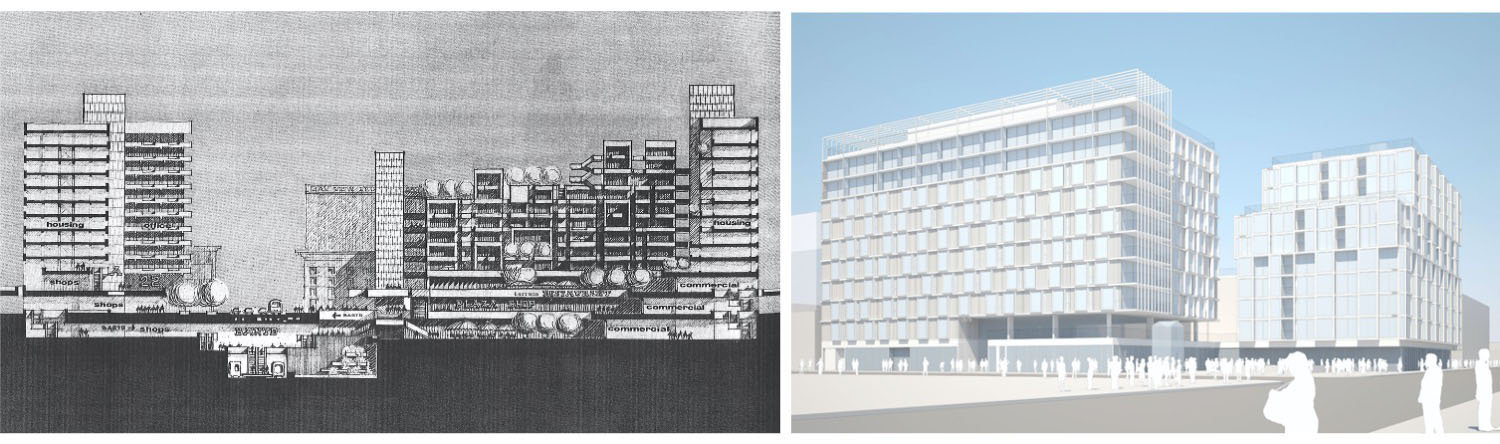

Fifty years later, those economic forces continue to transform the neighborhood into a site for capital accumulation. And, like 50 years ago, the community continues to fight back – marching to City Hall, calling out the opportunists, making their own counter-visions.

The last rally of the community before the pandemic hit was at the 16th Street BART Plaza, celebrating our victory in beating down the Monster in the Mission. The City has purchased what is perhaps the largest and most prominent development site in the neighborhood. The Plaza 16 Coalition, led by those new generations of women activists, fought against the Monster with their own vision, a Marvel in the Mission. In that 50-year arc of struggle, something new and different will be built at ground zero of the attempts at urban renewal by the State or by Capital.

My architecture students this Fall will be looking at this site influenced by memory, by 50 years of struggles, by culture, by the role of home in our life events, and by conversations with the people, with thanks to our elders.

Organizing is a long game, and the organizers themselves change, but memory and connection are critical. On the day Yolanda died, we gathered at 17th & Folsom, under Jess Sabogal’s mural on the new affordable housing building. The mural could have gone many ways: a safe abstract floral design favored by the architects, or an in-your-face memory of community and cultura. Jess’s mural is a gateway to the neighborhood, a reminder of all we have fought for and continue to fight for: an acknowledgement that all we do is on Indian land, that la Virgen de Guadalupe can shorten her heavy dress and wear heels if she wants to, that we have to say Basta Ya! when that is needed, and that our elders are looking on with uncompromising eyes, and not letting us give up the fight.

Yolanda L ópez, ¡Presente! Serve the People!

I am so moved by this 50-year history and the importance of art and culture as part of it–amazing murals on the buildings in the last picture! –Caroline Wildflower