“If you all stick around long enough today, you’ll start to feel it in your throat. Your nose feels sore, back of your throat feels raw.” Greg Lancaster* is telling us about the new air in his neighborhood in rural Butler County, SouthWestern Pennsylvania. Twelve of us are gathered in their modest living room inside a trailer that he and his wife Susanne have spent most of their lives, and their children’s lives, calling home. We’re a scant 45 minute drive North from Pittsburgh, and we’ve come to meet folks living in one of the epicenters of natural gas drilling in the Marcellus Shale – specifically, folks who no longer have drinking water, bathing water, or clean air to breathe. Gallon water jugs bulwark the front doors of their humble homes.

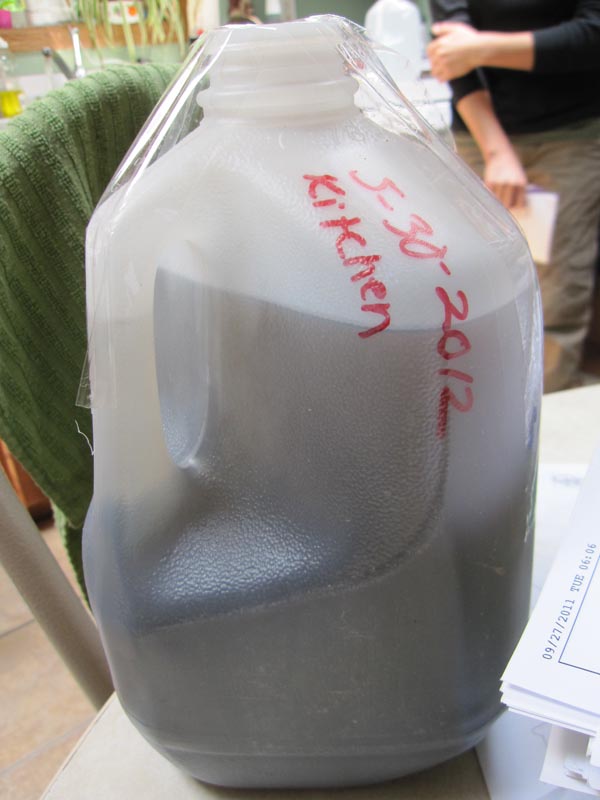

“We live by our means”, Susanne tells us. It used to be the now-dispersed Lancaster family would gather on Sundays at her home for dinner, and the kids would bring jugs to fill from the water well they’d grown up on, still preferring it to the wells at their own homes. One week last year, after their regular Sunday supper, Susanne got the call that her granddaughter was projectile vomiting, diarrhea running uncontrollably down her legs. “Quit with the formula” was Susanne’s advice, but by the next morning she and Greg were bed-ridden, and the extended family spent the next week thinking they had the worst flu to hit Butler County in decades. That was until Greg turned on their kitchen sink one afternoon and it spewed an intermittent, purple foam.

EPA testing found high levels of toluene, a benzene derivative that continues to be found in alarmingly high levels in areas of the country where hydraulic fracturing of shale deposits is the current trend in natural gas extraction. The Lancasters didn’t sign on for any of this drilling. They were aware that it was happening in Butler County, but they had been assured it was a safe practice, and, anyway, they and most of their neighbors aren’t in positions to choose whether to lease their land or not. Now Susanne has found herself running a weekly water drive through local churches and individual donors, just to get her and twelve neighbor families enough water to survive. More families need help, but Susanne is stretched too thin.

After a series of visits by EPA testers, during which the Lancasters were told that their contamination was the result of aged oil wells that had collapsed in the area (and that the nauseating odor from their water well was the smell of common slugs), the extraction company in the area, Rex Energy, retracted their promise to supply drinking water to any local residents. Susanne would later pay for private air testing, and find carbon tetracloride, freon, and benzene in her daily breathing ration. Acetone and chloromethane turned up in further water tests.

Driving around the area, Susanne showed us refuse ponds next to multi-generational apple orchards. She pointed to odd, generic-seeming tanks labeled “Produced Water” which, prior to their new labeling, spewed a chemical into the air like clockwork every afternoon that would “about knock you over” from nausea. Some homes along the way had temporary walls built between them and new neighboring Rex Energy facilities.

We visited her friend Jennifer, who has to move from her home entirely. She’s trying to get her house sold, but so are a lot of people, and it’s not easy to sell a house that will never have running water again. Jennifer’s house was assessed at something like $130,000 three years back, now she’s lucky to get $15,000. “If this guy doesn’t go through with the sale, I’m gonna just give it back to the bank and say ‘good luck’. There goes my credit, but I can’t live like this.”

Jennifer’s kitchen is littered, like Susanne’s is, with plastic gallon jugs of drinking water and dated, murky dark samples from her house spigots. A methane detector sits on the window ledge above the kitchen sink. She turned on her kitchen faucet while we gathered around, letting the water accumulate as a deep purple into a white plastic mixing bowl in the sink. Soon the stream itself was fully black.

Susanne tried to light the bowl of water on fire – they’d never tried with Jennifer’s water, but their neighbors had all done it with theirs. Matches weren’t setting a blaze, so I lent Susanne my Zippo lighter. She coaxed it around the surface of the dark pool, and although she couldn’t make it catch, the surface stiffened and coagulated when the flame was concentrated enough. Eventually the lighter grew too hot – it burned Susanne’s finger, and she instinctually dropped it, right into the white bowl of who-knows-what. In four inches of Jennifer’s black kitchen water, you couldn’t see to the bottom of the bowl where the silver lighter lay. We all laughed nervously and looked at each other – none of us really wanted to reach in to retrieve it.

Energy extraction companies rely heavily on the remoteness and secrecy of their operations in concert with their well-funded propaganda about job creation and environmental safety. And, much like blowing off the tops of mountains in rural West Virginia and Kentucky, to those of us in more urbanized locales, drilling for gas in Pennsylvania (and elsewhere) is a quiet nightmare happening “somewhere else” other than the urban environment.

The week after our visit to Butler County, my father sent me a clipping from a newspaper in central North Carolina, not far from where he and my mother have lived since moving out of Memphis three years ago. Local government there is fast-tracking legislation to get gas companies set to drill sooner than later. The talking points – about environmental safety, about the creation of localized jobs, about domestic energy production – were eerily familiar.

Marcellus Protest

Earth First! Marcellus

Pipeline (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette)

* because residents who have spoken out against the destruction of their homes have been personally threatened, all names in this article are pseudonyms.

Here’s some more suggested resources:

Tour De Frack – http://www.tourdefrack.com/

Marcellus Outreach Butler – http://www.marcellusoutreachbutler.org

OccupyWell St – http://www.owsstopfracking.org/

Save Riverdale – http://www.saveriverdale.com/

Protecting Our Waters – http://protectingourwaters.wordpress.com/

OhioFracktion – http://ohiofracktion.com/

Great post Shaun. Personalizes the fracking issues in ways that many other writings do not. The black water coming out of the tap is horrifying.