This week I’m going to close out my sub-series on Small Press Africa with sixteen books from Southern Africa. I hope people have enjoyed checking these books out as much as I have collecting and researching them. Africa is the second most populous continent, yet the only one without an Amazon.com site. It’s depressing to me how little culture makes it over here from there, and even though African authors are becoming increasingly popular in the U.S., it’s almost always based on novels about immigration experiences in the West rather than life in Africa (not that there is anything wrong with these novels, some are really good!).

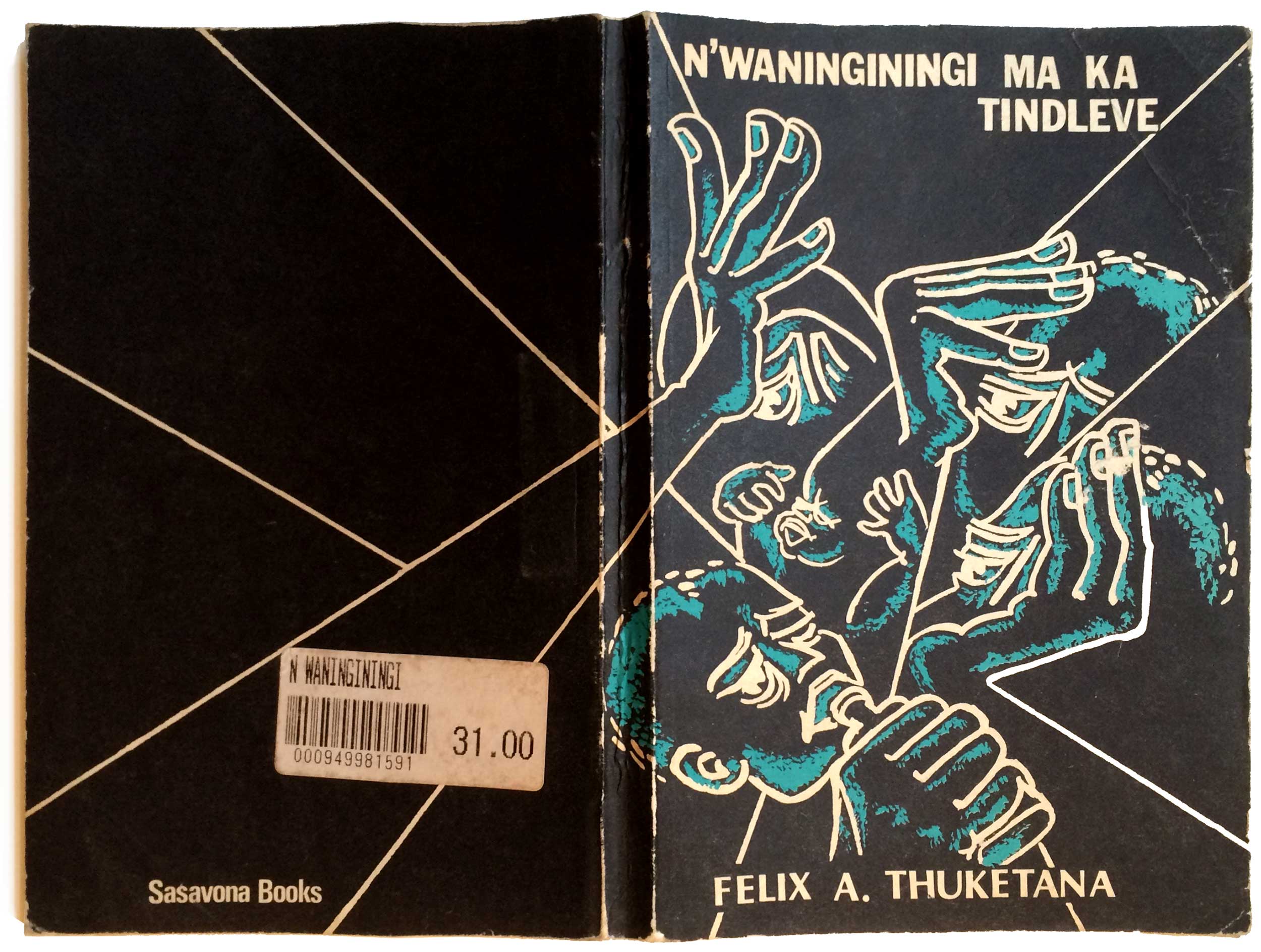

While overall books from Africa are pretty rare in the U.S., in general it’s much easier to find books from the Southern half of the continent. South Africa has a large and far-ranging book trade (not surprising since it also has the largest economy in Africa), with dozens of publishers putting out fiction and non-fiction in English, Afrikaans, and a half dozen African languages. The above is a book in Tsonga, a language from the Bantu family originating on the Northeast edge of South Africa and into Mozambique. N’waninginingi Ma Ka Tindleve roughly translates as “He Who Does Not Listen,” and is a crime novel, published in South Africa in 1978 (this is a second printing from 1981). The cover is brilliant, a sea of hands and heads thinking, listening, gesturing, and drinking. The faces appear fractured, the illusion created by cubist-like slight of hand with cascading diagonal lines doubling as arms for each of the hands. Like so much African output, the cover is printed simply in a nice duotone. In addition, the title and author are set in similar, but different typefaces, an odd decision that seems more haphazard than intentional.

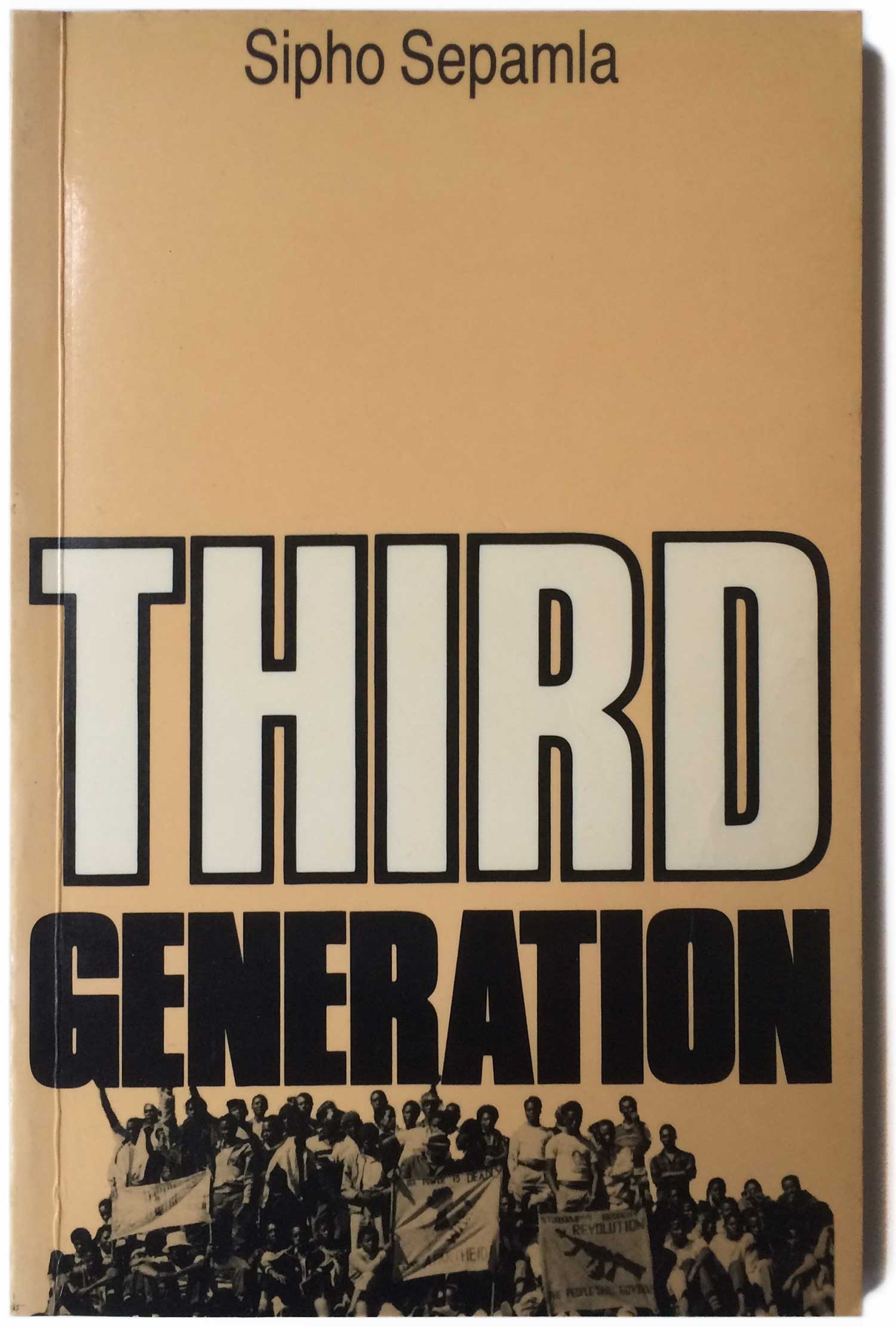

A small sub-set of South African publishing developed directly out of the anti-apartheid struggle and the increasingly prominent role it played in society from the late 1970s onward. Although much direct anti-apartheid activity was banned or curtailed by the government, but the early ’80s the movement had grown in such size and scope that it was hard to keep a lid on it. A number of small publishers sprung up to publish what is now called “Struggle Literature.” It’s a bit of a controversial moniker for a couple reasons—it implies that the author is necessarily Black, and that the writing is acceptable for the struggle, but not really “good literature.” Although out of favor in South African academic circles, I like struggle lit a lot, and find thinly-fictionalized first person narratives of political action fascinating and compelling. A couple of the publishers that sprung up to print and distribute this work were Skotaville and Ad. Donker.

Skotaville was the first black-owned and operated press in South Africa, founded in 1982 by author Mothobi Mutloatse (who was also involved in starting the anti-apartheid journal Staffrider). It was a non-profit project, funded by donations with the motto “Publishing by the people, for the people.” The two books below I found in South Africa, and I don’t think I’ve ever actually seen a Skotaville title in a store in the U.S. The press was apparently named after Mweli Trevor Skota, African National Congress (ANC) activist from the 1920s through the 1950s. Although named after Skota, it was not a strictly ANC press, and published authors connected to different factions of the liberation struggle. Apparently they had quite a list by the 90s, mostly political titles, but across fiction, poetry, history, education, theatre, and contemporary culture, including a title by Archbishop Desmond Tutu. I believe they published into the early 2000s, but appear to have gone out of business. Even with hundreds of titles, I’ve never seen a single one in a bookshop in the U.S., and the two below I found in South Africa!

Both of these are struggle novels, and Sipho Sepamla is arguably the master of the genre. Third Generation isn’t one of his “major” works, but a strong novel focused on the role of women in the anti-apartheid struggle. I really dig the cover, for its simplicity and boldness. The top half of the visual field is blank excepting Sepamla’s name, smartly rendered in an unassuming and thin sans serif. The bottom half if jammed full, mostly with the giant title, but also anchored with a great photo of a large group of protesters carrying banners with fists in the air. The cover of On The Eve features a tense painting by Durant Sihlali of the Sharpeville Massacre. the same bold titling font is used, but here it doesn’t work nearly as well. The painting is busy, so to make the title stand out they’ve outlined it with red—making the whole thing a little distracting. It’s interesting that these are some of the few African books from before the 1990s with 4-color process covers.

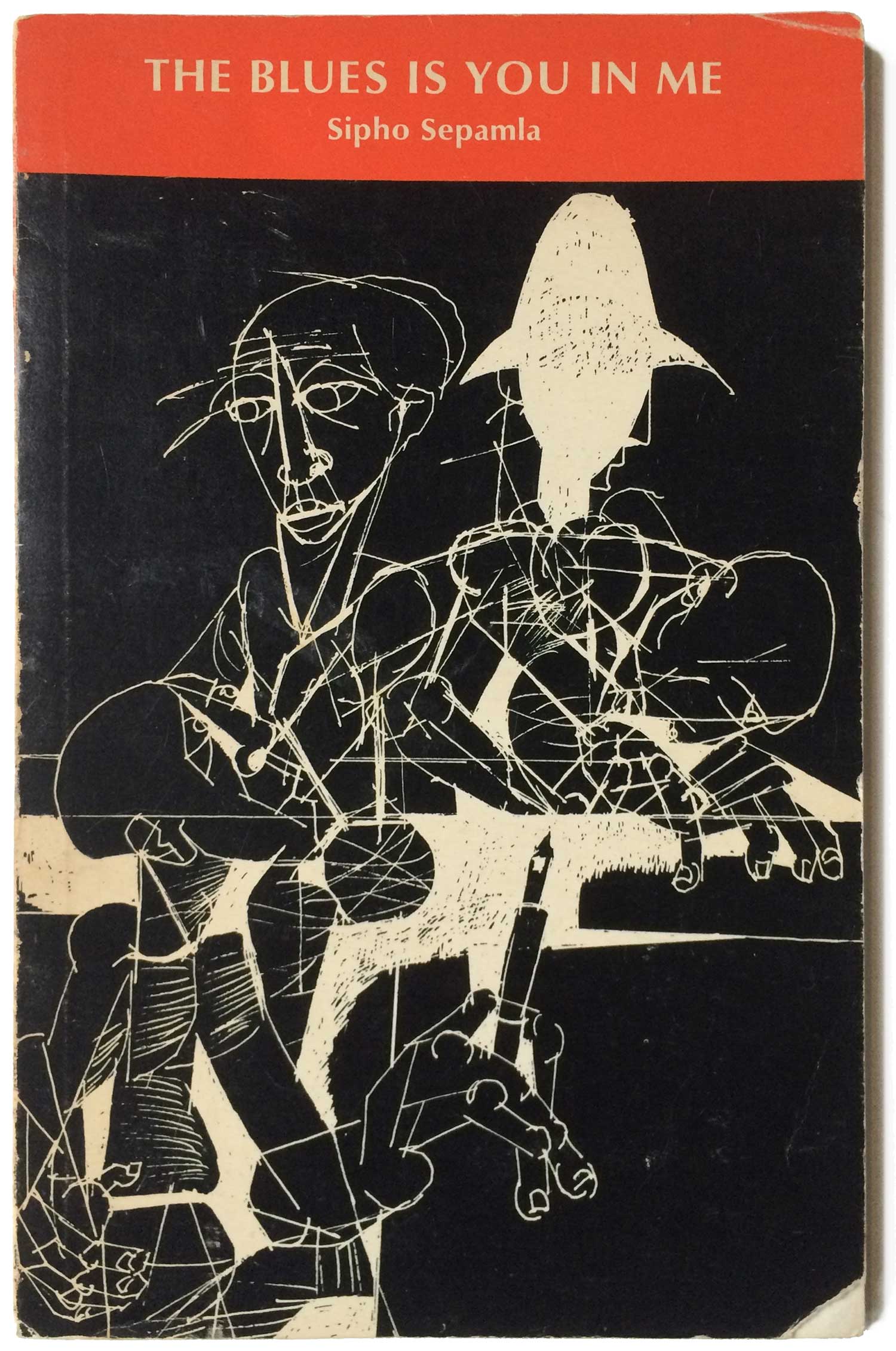

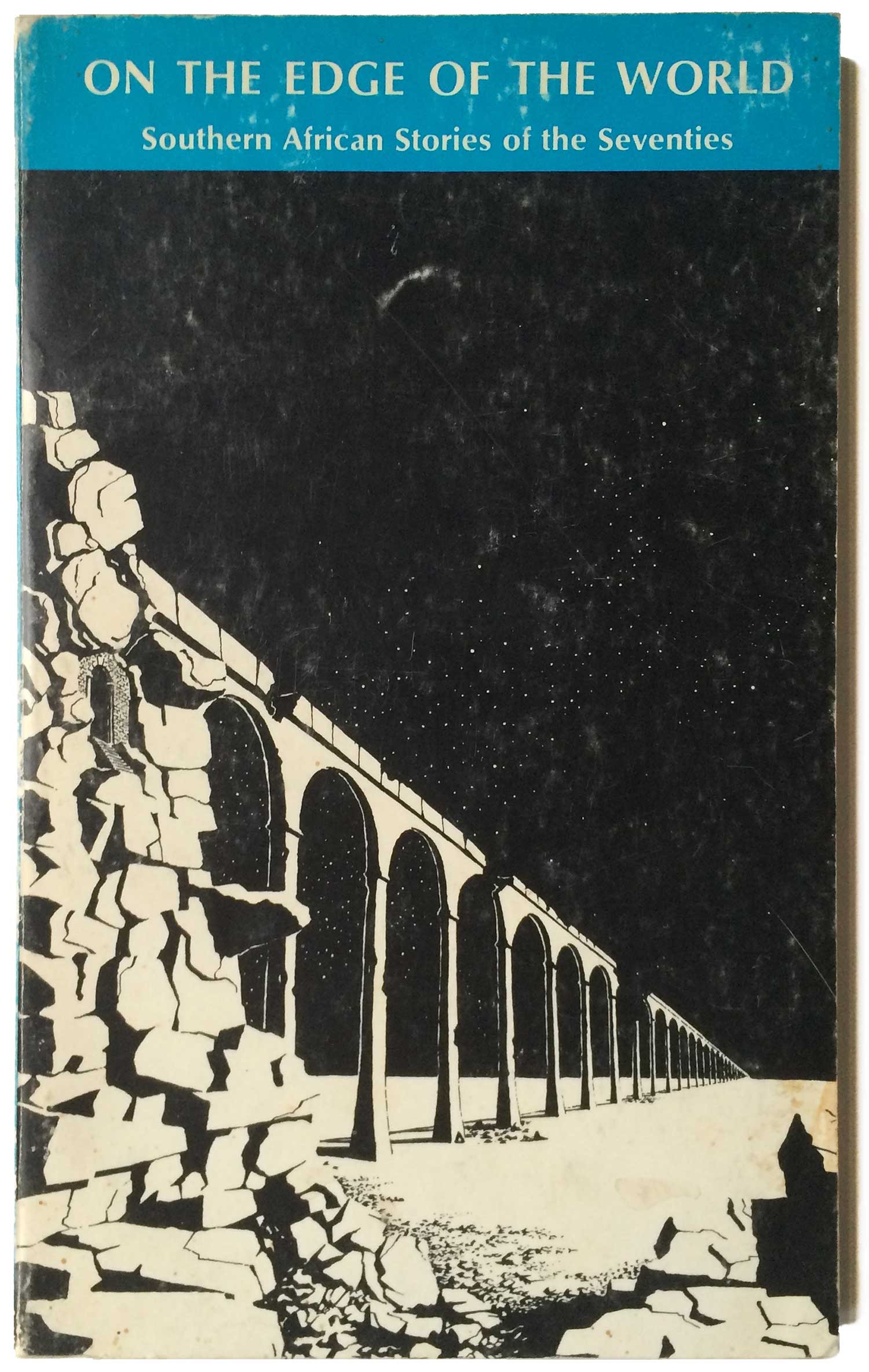

Ad. Donker was the publishing house of Adriaan Donker, a Dutch operator within the international book trade who originally went to South Africa in 1966 as a sales representative of Collier Macmillan. Ad. Donker was not an alternative or explicitly political press, but regularly published material that pushed the boundaries of the acceptable under the apartheid regime. They were the first to publish the above mentioned Sipho Sepamla, as well as ANC activist poet Wally Serote (who was also a key member of the Medu Arts Ensemble, who I featured way back in installment 38, and wrote about in Signal:03). The Blues Is You In Me is a collection of poetry originally published in 1976 (this edition is a reprint from 1980). The cover is duotone, with a really nice illustration by N. Mokgosi. The designer has decided to let the image speak for the book, placing the author and title in small and simple white type of a short orange band across the top. The back cover features a full-page author photo by Stephen Gray. Speaking of Gray, he is the editor of the collection of short stories to the right, On the Edge of the World. The design is basically the same, with a large format illustration—this time by Keith Alexander—and the titling in in white on blue banner. One of the things I like about both of these covers is how abstract and open the images are. They are both definitely representational, but there meaning is relatively open to interpretation.

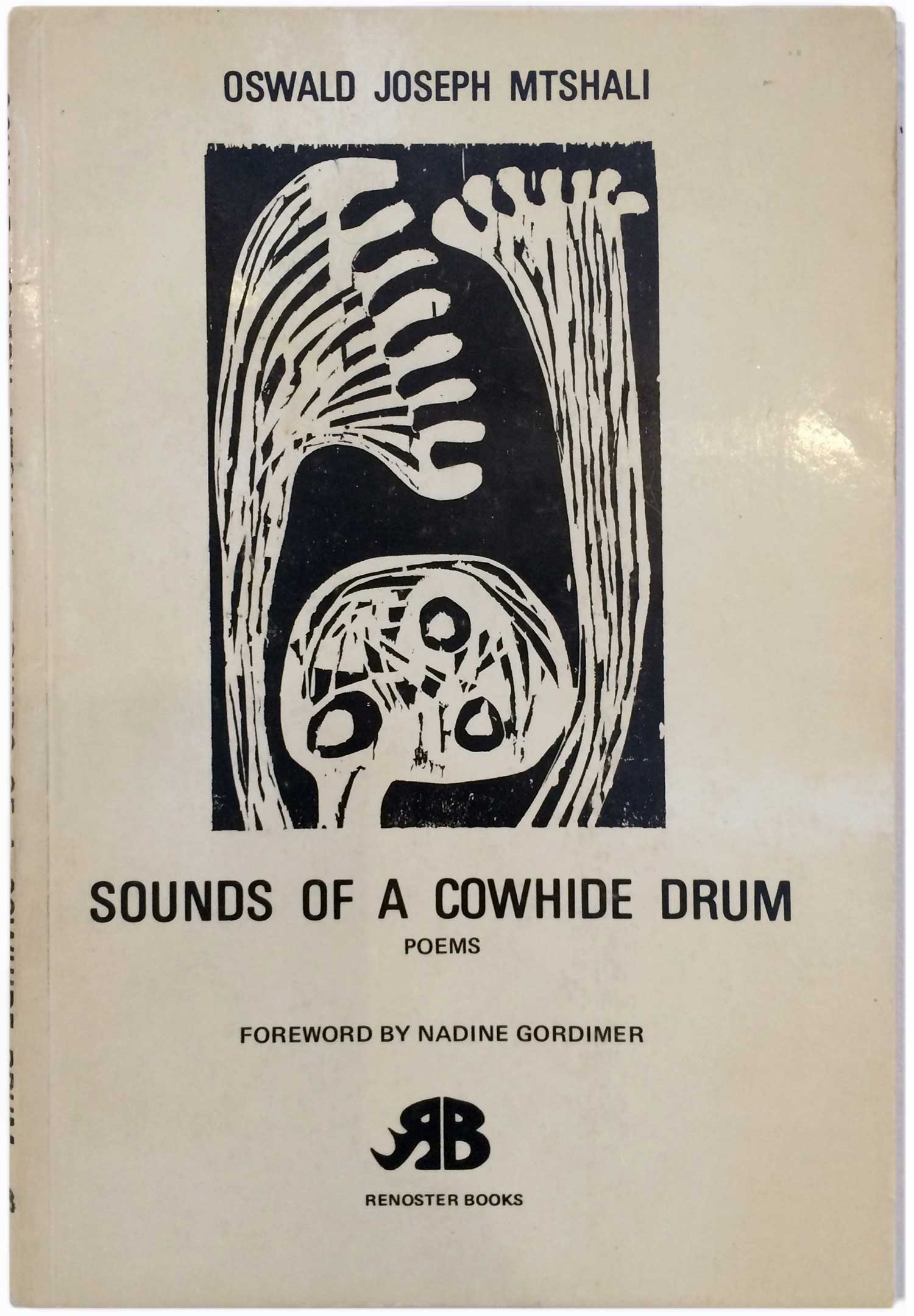

I’ve got one last S. African book, to the below left. Oswald Joseph Mtshali’s Sounds of a Cowhide Drum was one of the first, and most successful, books of poetry published by a Black South African. The edition below is of the sixth printing, bringing the total print run of the book to 10,000 copies, and that was in 1972, a year after initial publication. The book would go on to win multiple awards, and likely sold double that. Which is probably why I was able to find a copy kicking around at a NYC used book store. The cover is only mentionable because of the woodcut by Wopko Jensma. It’s in a relatively familiar Black South African woodcut style, but it’s a strong and strange image—the figure features fifteen fingers and while om the surface is reminiscent of The Scream, it actually evokes more a sense of being lost or confused than of simple horror.

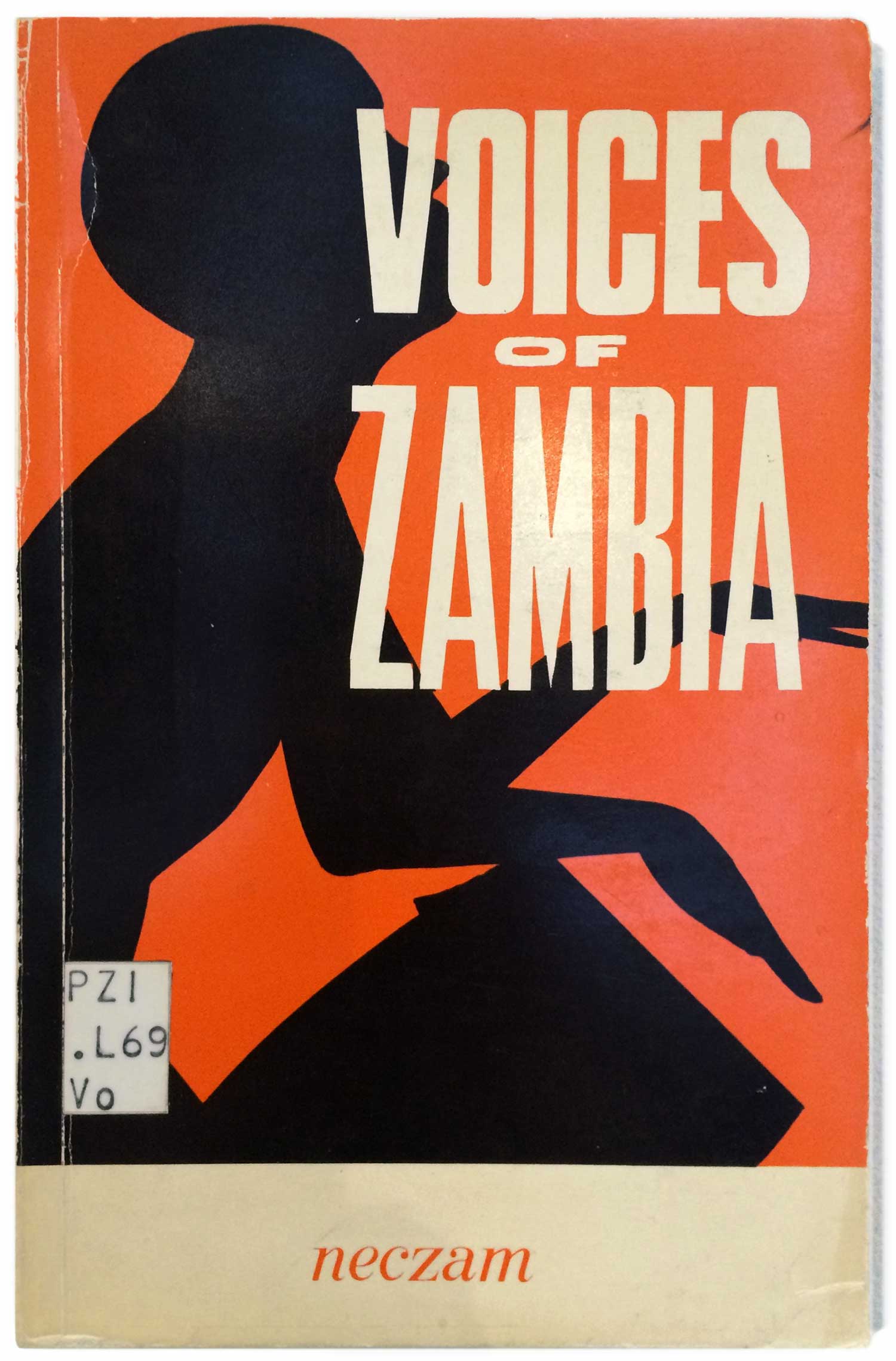

The next to books, to the right, are from Malawi and Zambia, respectively. And each is the only book I’ve ever found from either country. The inside cover of A Short History of Malaŵi shows a list of twenty titles from a “Malawian Writers Series,” running from 1974 to 1985 and put out by Popular Publications. The design of the cover definitely screams of series design, with its clean rows of boxes sandwiching a photograph—the text and image appearing completely interchangeable. It’s a solid design, with the top right dedicated to the series logo, the left to the title, the bottom right to the publisher, and the bottom left to the author information. The photo, a static-feeling image of what I guess is a building marking the border/entry point for Malawi, has an amazing caption which pretty much steals the show: “A People that is alive is building its future.” Voices of Zambia is just, a collection of prose by a stack of Zambian authors. It was published in 1971 by Neczam, or the National Educational Company of Zambia. This is another cover that just works so well because of its simplicity. The titling, with the vertically squeezed “of,” really sets off the silhouette of the drummer behind it.

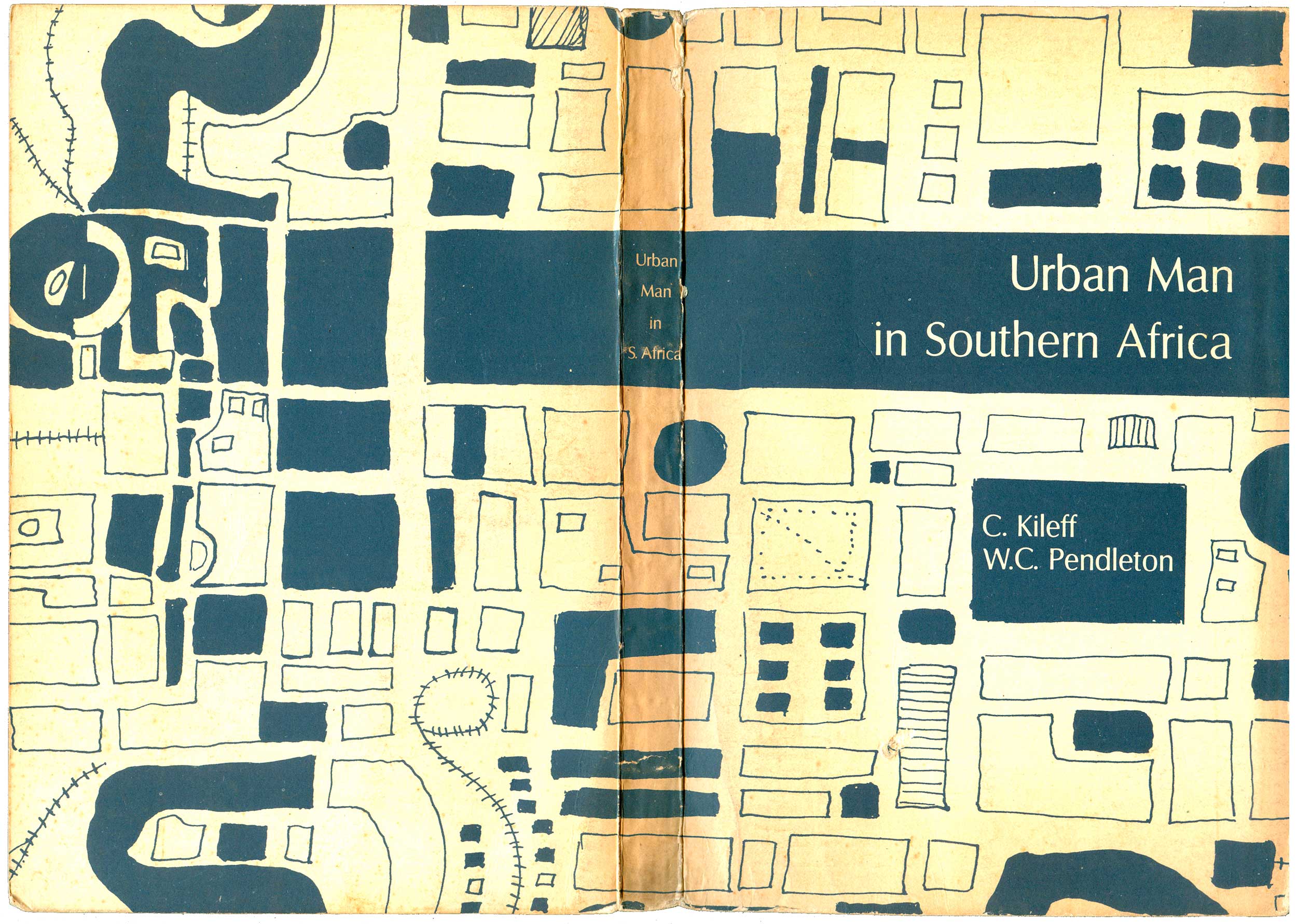

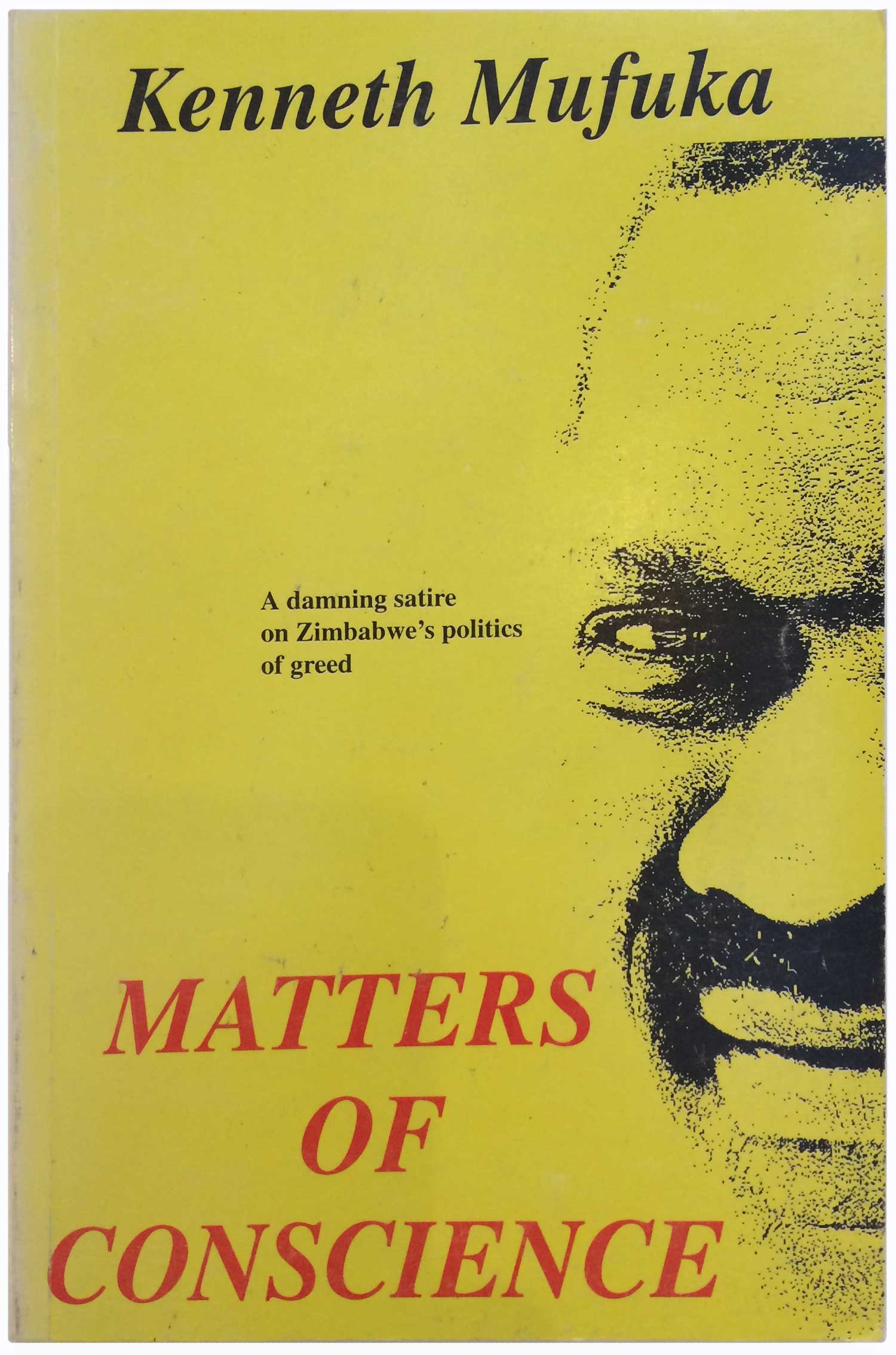

Zimbabwe is right above South Africa, geographically. Although there is no doubt that Mugabe, once liberation hero turned despot, is a brutal tyrant, Zimbabwe has maintained a pretty active and seemingly free book trade. The largest publisher is Zimbabwe Publishing House, which I featured here in weeks 208 and 209. Then there are dozens of other publishers as well, some of them with books below. Thing is, until 1980 Zimbabwe was a horribly backwards, racist, colonial state called Rhodesia. My sweet spot for the kinds of book design I love collecting is the mid-60s up until 1980, but there is little I’ve found from Rhodesia that seems that interesting. Below is an exception, a sociology book with a fabulous cover mixing mapping with “African” patterning and illustration style. The cover of Urban Man in Southern Africa is only one color, blue on a rapidly yellowing white stock, but that’s all it needs to be a compelling mash-up of architectural blueprint and ornamental design. The book was published by Mambo Press in 1975. To the right is another book published by Mambo, but in 1999. I haven’t been able to figure out if these are the same press, or have any relationship to each other. Kenneth Mufuka’s Matters of Conscience falls comfortably within the range of 90s/00s African cover design, basic imagery and text awkwardly assembled and produced poorly on cheap stock. The composition is interesting here, with so much negative space given to the left of the face. It’s almost as if the designer feared that much open area, so felt like they had to jam in the small tagline for the book.

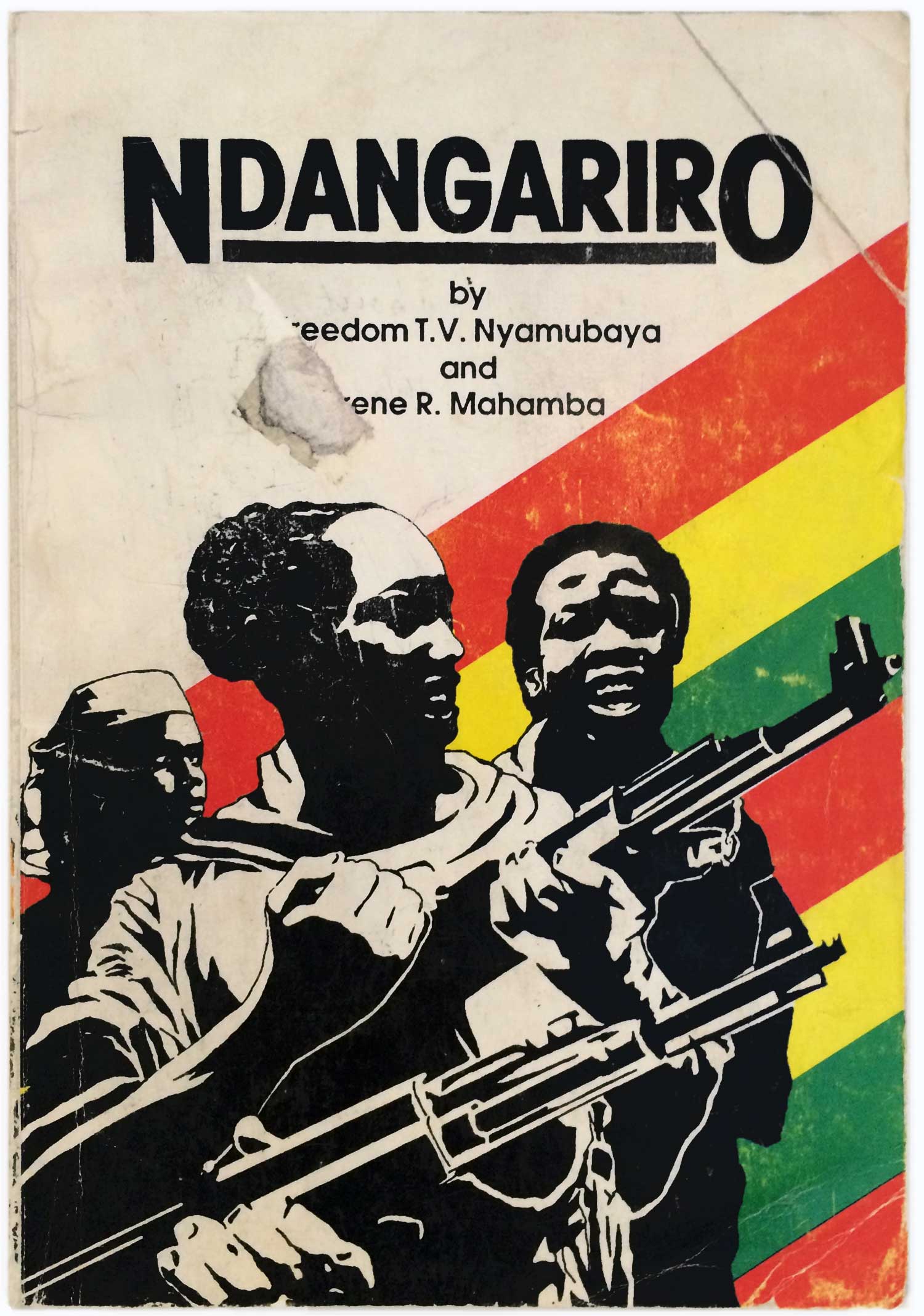

The below book was produced by ZIMFEP, or the Zimbabwe Foundation for Education with Production. “Education with Production” sounds like some sort of Stalinist New Speak, but it’s actually a popular education model in Southern Africa where book knowledge is always tethered to applied activities. There’s actually very little info about ZIMFEP or the book within the book itself, there is no colophon page, no publication date, nothing. The back cover speaks to telling the stories of women, but the front cover is all guns and glamour—a crew of guerrilla marching forward on a rainbow of red, green, and yellow, filling the role of the black stripe in the center of the Zimbabwean flag.

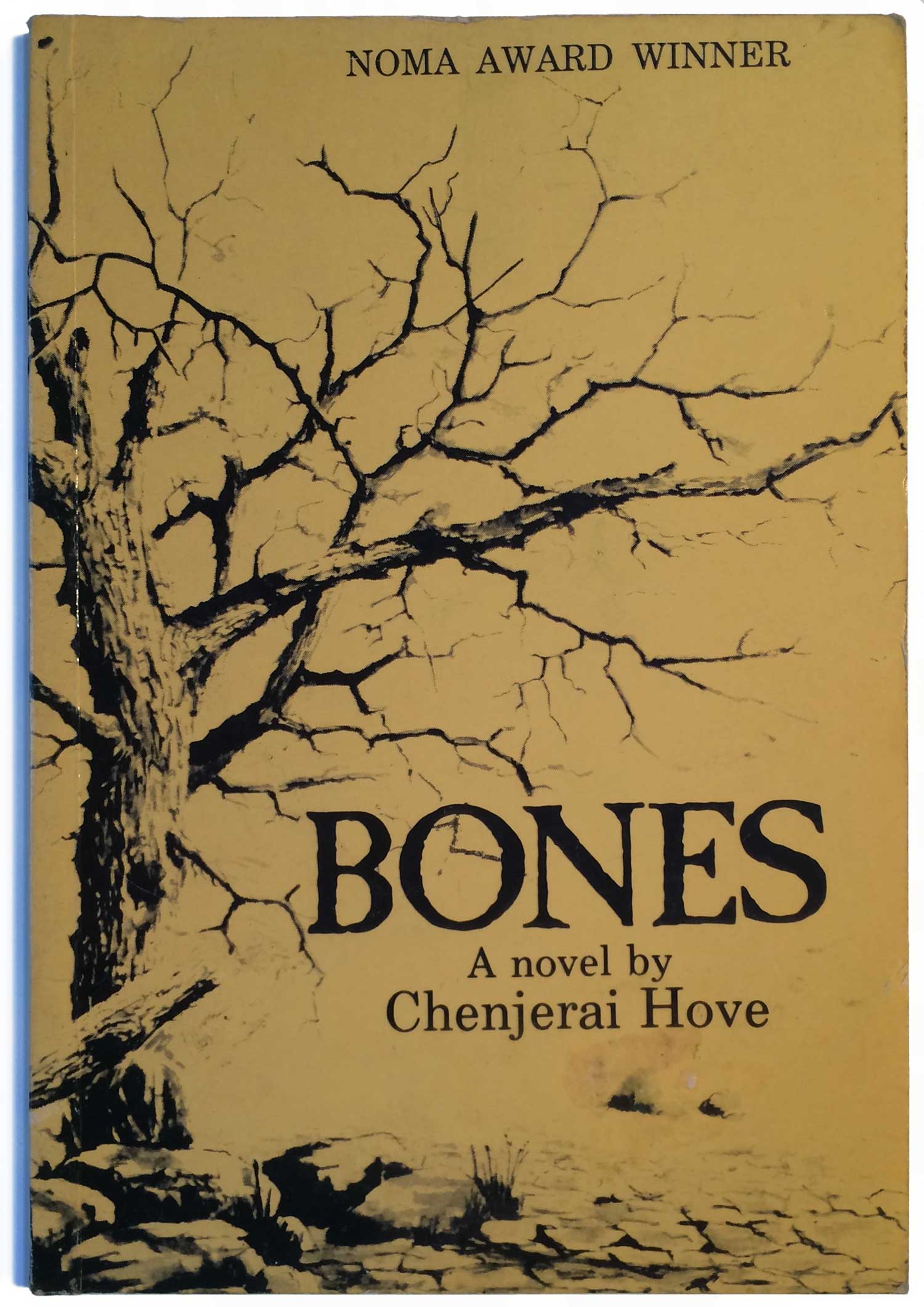

Chenjerai Hove (1956-2015) was one of Zimbabwe’s most celebrated writers. The two titles below somewhat bookend his writing career. Bones is his first and most celebrated novel, initially published in a version of the edition below by Baobab Books in 1988, it was picked up and republished as part of the Heinemann African Writers Series in 1989. To the right is Palaver Finish, a collection of essays from 2002 and one of his final books. The cover design of Bones is a case where having access to more than 2 colors for printing might have been extremely helpful. The desiccated landscape painting by Luke Toronga would be stronger with more complexity in the tones and color. The entire design would benefit from more depth, as the title and tree—both in the same dark blue—now live on the same visual plane, flattening everything out. Palaver Finish has all the qualities of 21st century low-rent publishing. The insides are print-on-demand and the cover is a strange, amateurish montage printed in sepia-tone for no apparent reason. The titling is in three separate fonts, with the first half of the title in digital 3D with fake shadows—desktop publishing gone horribly awry. (For another Hove cover, check out week 208.)

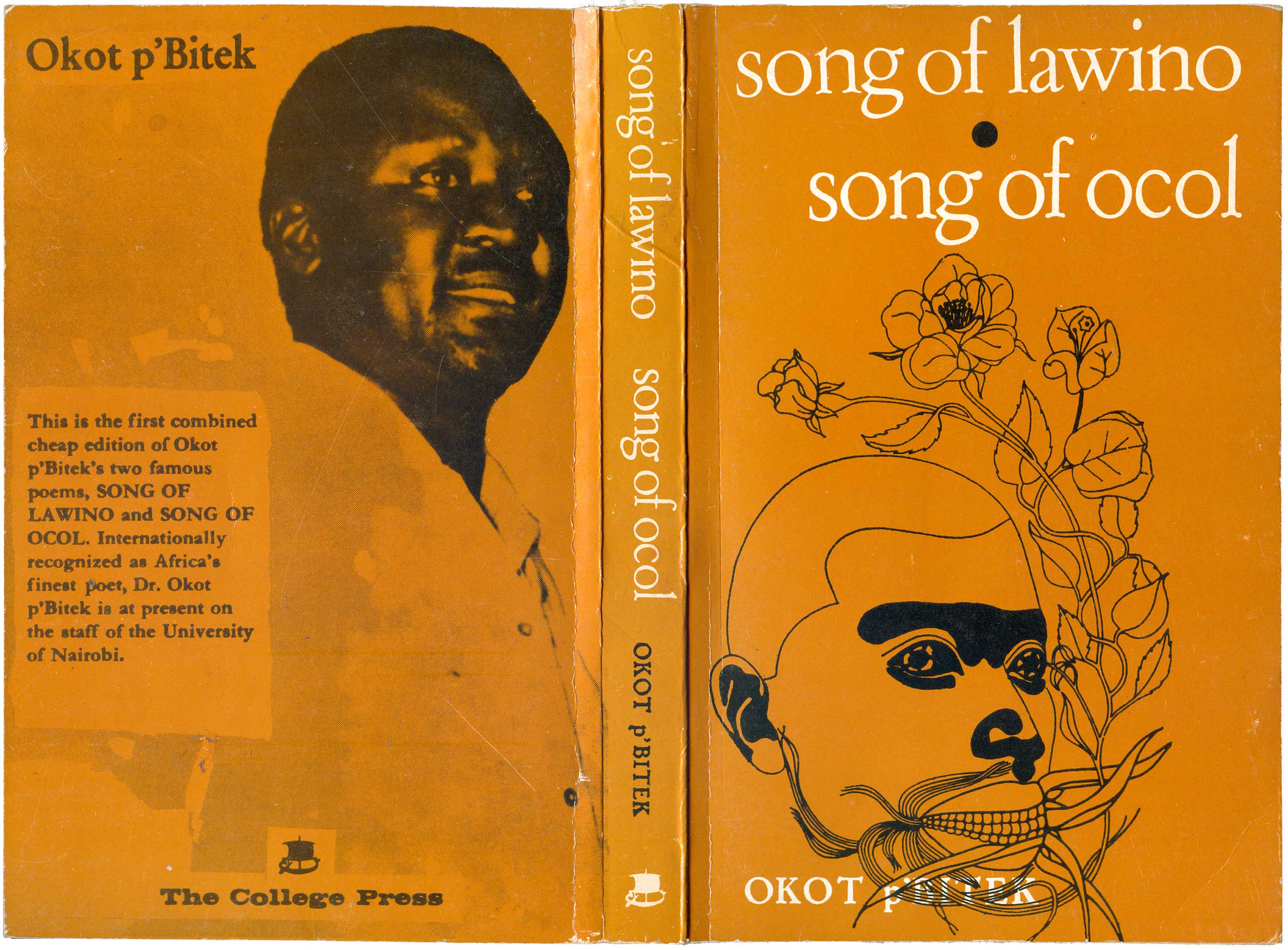

I already featured a couple College Press books back in week 225. For those that didn’t read that one, College Press is an educational publisher based in Harare and they’re still putting books out. Below is their edition of Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek’s Song of Lawino/Song of Ocol cycle. p’Bitek is one of the most renowned African poets, writing in his native Acholi then translating his work into English. This 1988 Zimbabwean edition is based on the version published by East African Publishing House in 1966, and maintains the fabulous illustrations by Frank Horley.

The final two books this week are also both from Zimbabwe. The first was produced by the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA), which is based in Dakar, but the book itself was published by Jongwe Press in Harare. The cover has the vibe of a bureaucratic report, which makes some sense since that’s kind of what it is. I do like the op-art effect of the black and white line switches that create the outline of Zimbabwe. The second book is a collection of poetry by Tafataona Mahoso published by Nehanda Publishers in 1989. Although part of a “Writers in Africa” series, with footprints in the shape of Africa featured on the cover, Mahoso is not that far flung—he’s actually a Zimbabwean career politician and conservative partisan of the ruling ZANU party.

Well, that’s it for Small Press Africa, for now. If you’ve got any thoughts, ideas, things I missed or got wrong, books for me, etc., let me know! Leave comments on these posts so that I know that you’re reading!

I’m not 100% sure what is in store for the next couple months. I’ve been slowing pulling together books for a series of posts on designers/artists (as opposed to regions or political issues), including Antonio Frasconi, Ben Shahn, and David King. Keep an eye out for those.

This week’s bibliography: