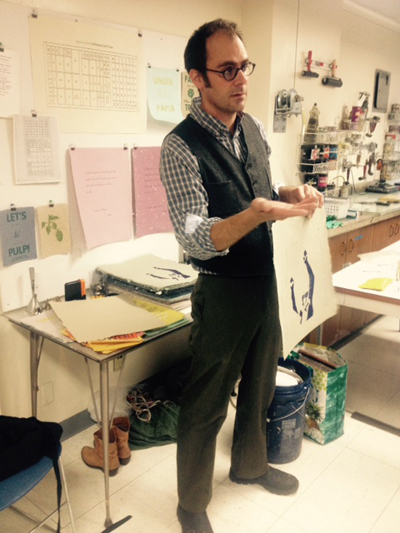

Another excerpt from A People’s Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice Movements that was published by The New Press last November. This excerpt focuses on the Combat Paper Project – a group that Justseeds has some personal history with. In 2013 Justseeds collaborated with Drew Cameron during the Southern Graphics conference in Milwaukee where Drew and Robert from Black Hawk Paper set up shop for a week and created a new body of work. This past week, Drew Matott and Margaret Mahan have been at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee doing workshops in the Printmaking Department. Drew was a co-founder of Combat Paper and now he and Margaret co-run Peace Paper. It is great to see both Combat Paper and Peace Paper doing such important work across the country and the world.

PAH excerpt:

From Uniform to Pulp, Battlefield to Workshop, Warrior to Artist

“We all have the ability to do something. We can push back.” —Drew Cameron

Creative resistance as personal and political action is also at the center of the Combat Paper Project by IVAW member Drew Cameron and artist Drew Matott. Cameron was deployed to Iraq in 2003 and served in the 75th artillery. In 2007, three years removed from active duty, Cameron put on his uniform outside his home in Burlington, Vermont, and asked a friend to take photographs of him cutting it off with a pair of scissors. He recalls, “My heart started beating fast. It felt both wrong and liberating. I started ripping it off. The purpose was to make a complete transformation.” His action provided the impetus for the Combat Paper Project. Cameron teamed up with Matott at the Green Door Studio in Burlington and learned the art of papermaking, and then they shared this process with the veteran community.

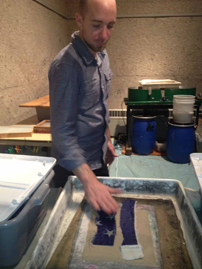

The Combat Paper workshops involve veterans shredding their uniforms into small pieces, mixing them with water, and pulping them. The pulp can then be made into sheets of paper for veterans to use for printmaking and personal journals. The process becomes a form of therapy, and the art a means to generate a larger conversation with the public about the reality of combat in Iraq and Afghanistan. Cameron explains:

The story of the fiber, the blood, sweat, and tears, the months of hardship and brutal violence are held within those old uniforms. The uniforms often become inhabitants of closets or boxes in the attic. Reclaiming that association of subordination, of warfare and service into something collective and beautiful is our inspiration.

To reach other veterans, Cameron and Matott held workshops in Burlington, and then took the workshops on the road and traveled extensively throughout the United States and abroad. They met with other veterans from the Iraq War, Afghanistan War, Gulf War, Bosnian War, Vietnam War, World War II, and the Korean War, who subsequently turned their uniforms into paper and personal expressions.

For participants, the act was one of release. Eli Wright, who served as an Army medic, explains, “This project saves lives, it gives us direction—to find we can build bridges and tear down those walls and remake sense of our lives.” Donna Perdue, a Marine Corps veteran, states, “Most of the therapy actually comes while shredding the uniform. During this time, participants are cutting small 1” pieces that make it easier for the beater to turn it into pulp later, and honestly, memories are being triggered . . . People start talking quietly at first, and then the floodgates open.”

Jennifer Pacanowski, an Army medic who served in Iraq from 2004 to 2005 and was later diagnosed with PTSD, recalled, “I just started cutting my uniform up, and before I knew it, I was sweating and my hand was bleeding. It was so satisfying. I can’t even describe it . . . like just destroying a really bad memory.” Leonard Shelton, a forty-four- year-old Marine Corps veteran who served for twenty years, adds:

I was in the process of throwing the [uniforms] out when I learned about this [the Combat Paper Project] and thought, I want to make paper out of this so I can write on it. I remember standing in front of the mirror when I got out and saying, who are you? I didn’t know. They [the military] told me where to go. They told me what to eat. They told me to cut my hair every two weeks.

Shelton fought in the first Gulf War, and was diagnosed with PTSD just before he was to be shipped out to Iraq in 2003. He retired from the Marines in 2005 and now receives a check for $207 a month.

Other veterans had similar reactions. Jason Hurd, a Tennessee National Guard veteran who served in Iraq in 2004 and 2005, stated:

When you hold these strips in your hand, you think about all the times you ironed it and spit polished your boots—all that was something the Army made you do. This is my uniform now. I’m not Army property anymore, and neither is it.

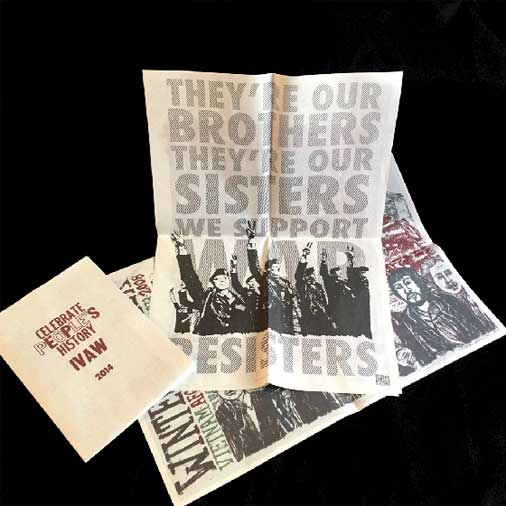

The images that veterans put on paper are as intense as the reasons for making the work, and the paper itself.

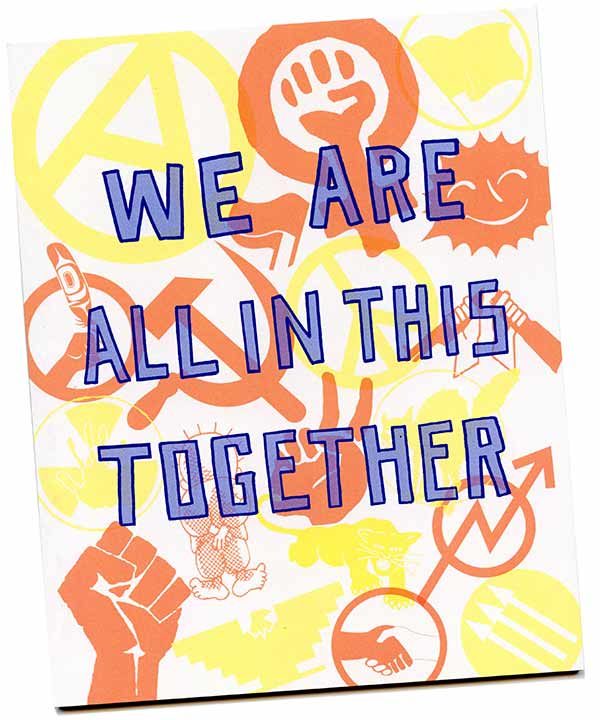

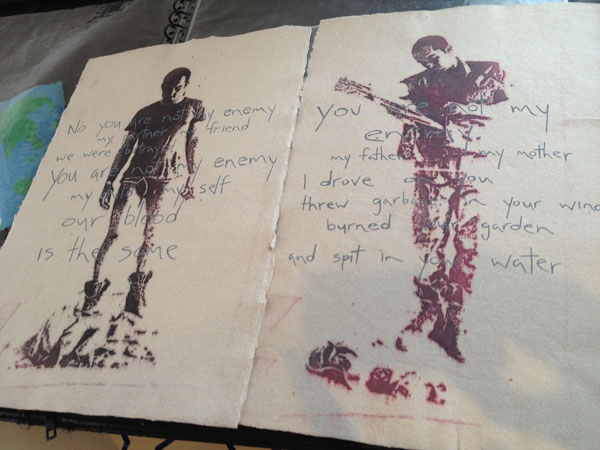

Jon Michael Turner created a silhouette image from the dog tag of his friend who was killed in action in Iraq. Eli Wright created Open Wound—red ink splashed on paper with a hole torn in the center as if the paper were a body. Cameron’s initial images were screen prints of photographs of him taking off his own uniform and included a poem entitled “You are not my enemy”—a message to the Iraqi people. Another print by Cameron shows a soldier and the U.S. Army logo. The text reads, “There’s Wrong and Then There’s Army Wrong: Resist Today”—a takeoff on the “Army Strong” campaign that helped recruit so many young men and women into the military. Cameron then littered the print with gunshots.

image by Drew Cameron

Other participants were less critical of the military. Zach Choate, a veteran who served as a gunner in the 10th Mountain Division, stated, “I’m hoping I come out of this a little more whole, a little more at peace. I’m not an anti-war, anti-military person. This is just me fixing me.” Choate adds that the project has provided him with a sense of community, helping him find other veterans to talk with and share experiences. “Each one of these guys I meet along the way, they’re like family now. It’s already helping. I’m starting to get the good feeling.” Aaron Hughes concludes, “War is such a destructive force. A part of the healing process, or a part of transforming out of that person who was part of that destructive process, is doing things that are creative—producing culture and finding a way to tell stories that are constructive instead of destructive.”

http://peoplesarthistoryus.org/

http://justseeds.org/nicolas_lampert/03pahbook.html

http://www.ivaw.org/

http://www.combatpaper.org/

http://www.peacepaperproject.org/

http://www.ivaw.org/war-is-trauma